Abstract: Foresight refers to the ability to make assumptions about probable future events based on the analysis of a situation. In a game of chess, for example, the player simulates his opponent’s next moves in his head and looks for the appropriate answers. This way of thinking has also gained importance in the military context. Suppose one applies the same logical principles to a different situation. If both cognitive processes were in complete agreement, everyone would have to arrive at the same next logical step that promises maximum benefit and minimum loss. In reality, however, human thinking is subject to numerous biases that need to be recognised and appreciated. Since life and complex conflicts go far beyond the binary decisions of a game of chess, for example, it is crucial to act beyond the limits of spatial and temporal thinking.

Problem statement: Of what underlying assumptions or beliefs are we unaware that make us vulnerable to manipulation by others?

So what?: Preventing the implantation of mental bombs into our minds is imperative. This necessitates a focus on mental education. Living a day in completely unknown, unpredictable and unexplained reality is a challenging exercise, yet it could aid in reducing biases and potentially uncovering new ones. The cognitive approach of the “Heimlich Manoeuvre” is one way of achieving cognitive resilience.

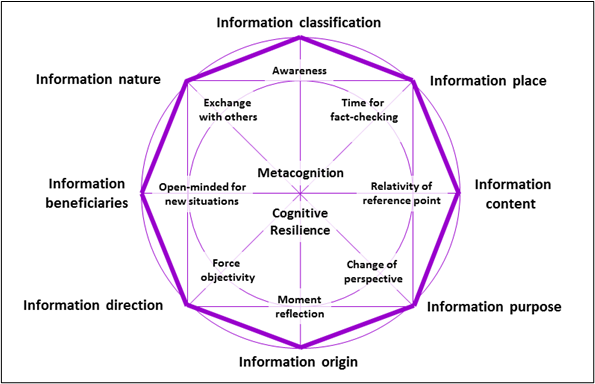

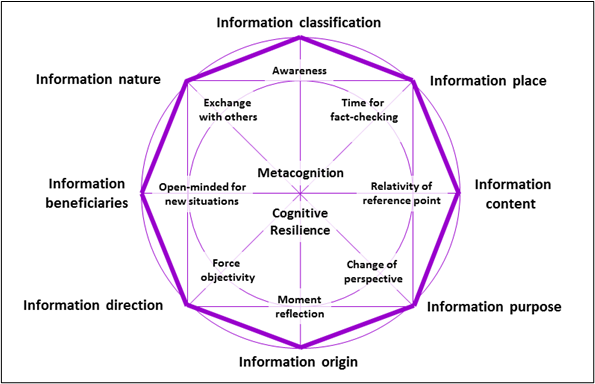

The Cognitive Octagon-Model© initiates reflective and self-critical examination of information processing within our cognitive system.

Information and Words as Weapons

The power of words is undeniable. The art of rhetoric and dialectic, which held great significance in antiquity, is still highly valued today, particularly in negotiations and debates. In ancient times, philosophers such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle developed comprehensive theories on the power of language and its influence on human thought and action.

Socrates employed the method known as “maieutic” or the “art of midwifery” to lead his students to the truth through skilful questioning.[1] Plato, a student of Socrates, engaged deeply with the ethics and morality of rhetoric, criticising the Sophists who often used rhetoric merely for persuasion without regard for truth.

Aristotle’s expansion on rhetorical ideas identifies three core elements: Ethos, Pathos, and Logos. These elements are integral to effective persuasion. Ethos refers to the credibility of the speaker. Aristotle emphasised that a speaker must appear knowledgeable and trustworthy to be persuasive. This involves not just the content of the speech but the speaker’s character and reputation as perceived by the audience.[2] Pathos, on the other hand, involves appealing to the emotions of the audience. Aristotle understood that emotional engagement can significantly influence an audience’s reception of the message. This can be achieved through storytelling, vivid language, and the speaker’s own emotional expression.[3] Logos, finally, pertains to the logical structure of the argument. It uses data, evidence, and rational arguments to support the message. Aristotle believed that a well-reasoned argument is essential for persuasion.[4] These elements should work harmoniously to create a compelling and ethically sound argument.

The Semiotic Triangle and the Power of Words

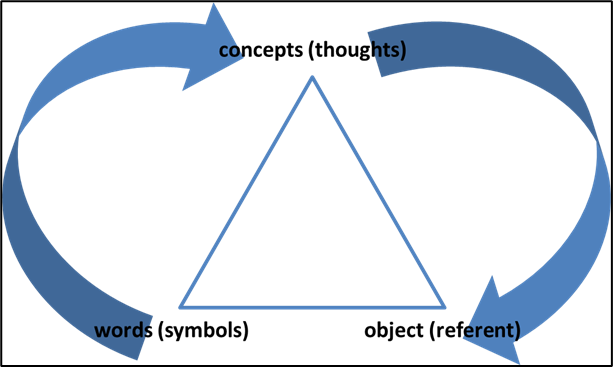

The semiotic triangle is a useful model for understanding the dynamics of language. It illustrates how words (symbols) refer to concepts (thoughts) and actual objects or events (referents). For example, when talking about “battle,” one has a word (symbol), an idea of a battle (concept), and the actual action or situation of a battle (referent). This model explains why words are so powerful: they influence human thinking, emotions, and perception of reality. In negotiations and debates, words can strategically provoke specific reactions and actions.

The semiotic triangle is a useful model for understanding the dynamics of language.

The idea of the triangle has many predecessors, including Gottlob Frege, Charles Peirce, Ferdinand de Saussure, and Aristotle. Ogden and Richards emphasise with the semiotic triangle that words, objects, and concepts should not be confused. The three vertices of the triangle represent areas that are inherently different in nature.[5]

The connection between the word (symbol) and the object (referent) is indirect and runs through the thought of someone. The word activates a mental concept in a human subject, whether speaker or listener. This mental concept is the idea.[6]

The semiotic triangle model of Ogden and Richards

Military Metaphors and Their Significance

The use of military metaphors in modern language, such as “outmanoeuvre” or “talk down,” is pervasive and reflects a combative nature in verbal exchanges. These metaphors illustrate how arguments and discussions are often framed as battles to be won, using terms like “ammunition,” “target,” and “attack” to describe rhetorical strategies. This linguistic pattern underscores the power of words to connect and harm, akin to how precise actions in battle can determine the outcome of a conflict.

For instance, the metaphor “argument is war” includes expressions like “I demolished his argument” and “She shot down all my points,” highlighting the adversarial stance often taken in debates. Similarly, phrases like “marketing is war” or “medical progress is a battle” indicate how various domains adopt combative language to describe efforts and challenges, emphasising struggle and victory.[7]

Language possesses the power to connect, heal or wound, similar to needles, and, therefore, has a dual capacity that must be used with care. Understanding these metaphorical frameworks can provide insights into how language shapes our perception of interactions and conflicts, and why it is crucial to use such powerful tools thoughtfully and responsibly.[8]

Emotional and Psychological Effects

Words can trigger immediate and powerful emotional reactions that affect both self-esteem and perception. These verbal injuries cause instant pain, evoke negative emotions, and attack human sense of self-worth. Verbal assaults are consciously perceived and can provoke intense emotions that linger in memories. For instance, many people vividly remember what they were doing on September 11, 2001, when they heard of the attacks on the World Trade Centre. These poignant memories exemplify how emotional events become deeply embedded in our memory.[9]

Words can trigger immediate and powerful emotional reactions that affect both self-esteem and perception.

A Metaphor for Cognitive Resilience

The Heimlich Manoeuvre, named after its inventor, American physician Henry J. Heimlich (1920-2016), saves lives by expelling foreign objects from the windpipe, thereby ensuring survival. This physical manoeuvre illustrates the critical importance of targeted external intervention in acute danger situations. Applied to the psychological realm, the “Heimlich Manoeuvre” also symbolises the capacity for cognitive resilience—the ability to recover from emotional injuries and think clearly.

Much like the physical manoeuvre requires direct, external assistance to be effective, the mental “Heimlich Manoeuvre” often necessitates support or an overarching perspective. In stressful situations, it is essential to seek help or to approach the situation from a broader viewpoint to find alternative solutions and better cope with challenges.

Instinctive and Reflective

Verbal injuries can trigger immediate biochemical reactions that impair human rational thinking.[10] This phenomenon is reminiscent of the “fog of war,” a concept introduced by Carl von Clausewitz, symbolising the unknown and uncertain in war, often leading to hesitant action. In such moments, thoughts become blurred because it is unclear what intentions the “opponent” might have.[11]

However, with technological advancements, particularly in intelligence gathering, the “battlefield” seems to be more transparent. On the one hand, movements and power shifts can be detected early on, and troop deployments can no longer be kept secret. On the other hand, the bombardment of information has created a different fog, making it more difficult to discern the facts. Despite these technological advances, emotional and psychological impacts persist, as they cannot always be immediately mitigated by clear information.

Instinctive Behaviour and Cognitive Strategies

The Heimlich Manoeuvre is particularly effective in moments requiring instinctive action during acute danger. Evolutionarily, humans respond to abrupt changes in their environment, whether physical or verbal, with flight, fight, or even freeze reactions for camouflage.[12] However, these instinctive responses can block rational thinking and action.

Each individual develops a unique worldview, filtering information according to personal values and norms, and tends to amplify desired information while blocking out the unwanted. This selective perception influences our behaviour and makes us susceptible to the cognitive strategies of others who attempt to manipulate this perception.

Obvious threats can often be quickly and effectively countered through simple defensive behaviour. However, insidious, less clear and immediate threats require deeper understanding and reflective action. Recognising subtle threats, engaging in self-reflection, and raising awareness is crucial for responding appropriately and finding the right solutions.

Subtle Change through Cognitive Biases

While the Heimlich Manoeuvre is a useful technique for eliminating acute threats and mental blockages—effectively defusing a “mental bomb”—the question arises of how to deal with subtle, unconscious changes that occur slowly and continuously. Such changes can influence humans over a prolonged period, altering behaviour and attitudes imperceptibly without awareness.[13]

The ultimate goal of such subtle influence is to shape beliefs and behaviours in a specific direction.[14] This type of influence is particularly insidious because it relies on human understanding of cognitive processes. Cognitive biases can manipulate our judgment and decision-making. Therefore, it is crucial to be aware of these biases and to reduce judgment errors to improve the quality and speed of our decisions.

Recognising and addressing cognitive biases involves self-awareness and critical thinking. By actively questioning assumptions and seeking diverse perspectives, one can mitigate the impact of these biases. Additionally, fostering an environment that encourages open dialogue and critical analysis can help us remain vigilant against subtle manipulations. This proactive approach enables us to maintain greater control over our cognitive processes and make more informed, objective decisions.

Recognising and addressing cognitive biases involves self-awareness and critical thinking.

Cognitive Biases and The Assassination Attempt on Donald Trump

The assassination attempt on Donald Trump can illustrate various cognitive biases that influence the perception and interpretation of events.[15] The confirmation bias[16] strengthens the tendency to seek, interpret, and remember information that aligns with one’s preexisting beliefs. For example, individuals with a positive or negative view of Donald Trump are likely to evaluate reports of an assassination attempt on him according to their bias. Trump supporters may view the attempt as evidence of a hostile environment, while his opponents might interpret it as a consequence of his polarising politics.

On the other hand, anchoring bias[17] influences how the first piece of information disproportionately shapes subsequent judgments. If the initial reports about the assassination attempt were dramatic or sensational, later, more detailed reports may receive less attention or weight.

Meanwhile, the availability heuristic[18] plays a role in how people assess the likelihood of events based on how easily examples come to mind. If assassinations or violence against politicians are heavily featured in the media, the perception that such incidents are more common than they truly may be amplified.

The fundamental attribution error also affects how people interpret behaviour, with a tendency to attribute others’ actions to personality traits while underestimating situational influences. For instance, Trump’s opponents might see his behaviour or rhetoric as the catalyst for the attack, whereas his supporters could be more inclined to label the attacker as mentally ill or an extremist, disregarding the broader political context.[19]

Moreover, groupthink can create pressure to conform within political circles, leading to uniform interpretations of events like an assassination attempt on Trump. This conformity often suppresses critical or alternative perspectives that might challenge the dominant narrative.[20] Also, hindsight bias plays a part, as people often claim they could have predicted an event after it has occurred. Following the assassination attempt, some may argue it was foreseeable, pointing to prior warnings or the intense political climate as evidence.[21] Finally, don’t let us forget negativity bias, which emphasises how negative events carry a stronger impact on perception than positive ones. The assassination attempt on Trump generated widespread media attention and public reaction, heightening the perception of danger and instability surrounding the event.[22]

These cognitive biases illustrate how complex and often distorted human perception and interpretation of events like an assassination attempt can be. They influence not only individual opinions but also public debate and political reactions. Therefore, it is crucial to be aware of these biases and to minimise judgment errors to improve the quality and speed of decision-making.

Another example that illustrates cognitive biases affecting security personnel, specifically bodyguards, is the assassination attempt on Oskar Lafontaine by Adelheid Streidl on April 25, 1990, at the Mühlheim City Hall in Cologne, Germany.[23] A woman who appeared to be an admirer approached Lafontaine and the North Rhine-Westphalia Minister-President Johannes Rau after a political rally. She presented each of them with a bouquet of flowers and extended a notebook to Lafontaine. While the SPD politician searched for a pen, she stabbed him in the neck with a 30 cm-long butcher’s knife. The bodyguards were misled and failed to recognise the potential danger. This failure could be attributed to the following causes: One factor is the underestimation of the threat. Due to the influence of normalisation bias and optimism bias, the security personnel may have assessed the likelihood of an attack as low, leading them to overlook the need for more stringent precautions. Another issue involves inadequate attention to warning signs. Confirmation bias may have caused them to disregard potential indicators of danger, especially if these signs did not align with their existing security framework. A third challenge is the failure to adapt to new information. The anchoring heuristic could have made it difficult for them to adjust their security measures in light of evolving circumstances, resulting in a rigid and inappropriate strategy. Finally, a false sense of security may have developed. The availability heuristic, coupled with optimism bias, might have created a misleading perception of safety, ultimately undermining the security personnel’s vigilance.

Cognition and Manoeuvre Warfare

The Royal Australian Armoured Corps Manoeuvre Warfare Handbook described Manoeuvre Warfare already in 1994 as followed:

“Manoeuvre warfare is a mental approach to conflict in which we seek to create and exploit advantage by creating a rapidly and continuously changing situation in which our enemy cannot effectively cope. We aim to do this by focusing our strengths against the critical enemy through ambiguity or deception.”[24]

Manoeuvre warfare is a mental approach to conflict in which we seek to create and exploit advantage by creating a rapidly and continuously changing situation in which our enemy cannot effectively cope.

Manoeuvre warfare aims to overwhelm the enemy through deception, disinformation, and rapid changes, leading them to make poor decisions. Simultaneously, one must protect oneself from such influences by developing cognitive resilience. It refers to the ability to adapt flexibly to new, changing, or unexpected situations while maintaining a solution-oriented approach. Mental and physical strength play a crucial role in this.

These concepts of manoeuvre warfare and cognitive resilience can also be applied to perceiving political events such as an assassination attempt. Just as in a military context, it is important to be aware of cognitive biases’ subtle, unconscious, and often insidious nature and develop strategies to counteract them. This requires both individual efforts to strengthen personal cognitive resilience and societal efforts to promote balanced and critical public debate.

Cancer is a fitting metaphor for gradual, unwanted, and unconscious changes. This disease often develops slowly and goes unnoticed until it becomes a significant problem. The comparison highlights the importance of being aware of such changes’ gradual and often subtle nature and taking early measures to “heal.”

Cancer Research and Consciousness Studies

At first glance, the connection between cancer research and consciousness studies may not be immediately apparent, as these two fields represent seemingly different scientific disciplines. Cancer research focuses on the biological, genetic, and molecular mechanisms of cancer and the development of diagnostics and therapies. In contrast, consciousness studies examine the phenomenon of consciousness, including perception, thought, emotion, and self-awareness.[25]

Despite these differences, some intersections and potential connections exist between these two areas. The separate consideration of different scientific subfields can likely be attributed to cognitive biases. This means cognitive processes may influence the tendency to view scientific disciplines in isolation. Cognitive biases are systematic thinking errors that affect our perception and decision-making. In this case, such a bias could lead to overlooking connections and potential synergies between different fields of research. They are perceived as independent and separate due to preconceived notions or patterns of thought.[26]

Psychoneuroimmunology

Psychoneuroimmunology is a relatively young interdisciplinary field of research that examines the interactions between the nervous system, the endocrine system, the immune system, and psychological processes (including consciousness and emotions). The immune system responds to neurochemical signals from the nervous and endocrine systems. Conversely, the nervous and endocrine system’s functions are influenced by signalling molecules from the activated immune system.[27] Stress, psychological state, and emotional well-being can affect the onset and progression of cancer. This suggests that consciousness and emotional health may play a role in the prevention and treatment of cancer.[28]

Neurobiology and Cancer

“Neuroscience of Cancer” explores how tumours grow and spread through interactions with the nervous system, forming complex networks that communicate with nerve cells. Recent findings have shown that tumours, such as glioblastomas (aggressive brain tumours), resemble neurons and use synaptic connections typically found between nerve cells. These connections allow tumour cells to repair themselves and communicate intensively with each other, enabling them to resist therapeutic attacks. This type of communication promotes tumour growth and spread, complicating treatment.[29]

Current research focuses on understanding these synaptic connections and the mechanisms by which nerve cells influence tumour growth. Prof. Dr. Frank Winkler, a leading senior physician at the Neurological Clinic of the University Hospital Heidelberg and the National Center for Tumour Diseases (NCT), also heads research projects at the German Cancer Research Centre (DKFZ). Along with his team, he has discovered in preclinical and clinical studies on glioblastomas that tumours can attract nerve cells and integrate them into their growth. Tumours use chemical signals and electrical impulses to stimulate and promote growth.[30]

Preliminary evidence from animal studies shows that interrupting the communication between nerve cells and tumour cells can curb tumour growth. Clinical trials are currently underway to determine how these findings can be translated to humans and whether existing therapies can be supplemented with new approaches.[31] Advances in cancer neuroscience could lead to new therapies that specifically target the nervous system to inhibit tumour growth.[32] However, many questions remain, and further research is needed to confirm the effectiveness of these new approaches in patients.

Early Detection and Countermeasures

Just as cancer can be detected early through regular screenings and the analysis of tissue and blood samples, enabling targeted therapies, it is also crucial to identify cognitive biases early on. These biases must be recognised, analysed, and resolved to implement appropriate countermeasures. The signalling and storage of environmental information in the brain can provide clues to cognitive biases, which can be considered “cognitive foreign bodies.” Building resilience and consciously integrating collected experiences are necessary to prevent future cognitive biases and develop stronger immunity against their negative effects.

Building resilience and consciously integrating collected experiences are necessary to prevent future cognitive biases and develop stronger immunity against their negative effects.

Adopting strategies to monitor and manage these biases can enhance cognitive resilience, allowing for clearer thinking and more effective decision-making. This proactive approach is akin to preventive healthcare, where early intervention can mitigate the impact of potential threats and promote overall well-being.

Cognitive Protocol

The cognitive protocol is an effective technique for recognising and correcting cognitive biases. This method, derived from cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), helps identify and analyse thought patterns. The key to creating a cognitive protocol is awareness of the situation. One must adopt a meta-perspective to identify and perceive biases. Figuratively speaking, one hovers above the situation to maintain an overview and detach from oneself to analyse details objectively. The guiding principle for this step-by-step approach is: “Learn from the past, live consciously in the present, shape the future.” The following steps should be followed:

- Describe the situation: Record the facts and try to identify who might benefit or suffer from the situation;

- Identify feelings and emotions: Listen to yourself, describe your emotional state, and identify any other emotions present;

- Capture automatic thoughts: Gain distance from the situation, note the spontaneous thoughts that come to mind, and identify them;

- Recognise cognitive biases: There are over 50 different types of cognitive biases, including the anchoring heuristic, the sunk cost fallacy, the availability heuristic, the Dunning-Kruger effect (where individuals dramatically overestimate their actual knowledge and competence in a specific area), the frequency validity effect (where a statement is perceived as more truthful the more frequently it is heard), the halo effect, and blind-spot bias. These systematic distortions arise from experiences, knowledge, and memories;[33]

- Develop alternative thoughts: Create realistic and balanced thoughts that reinterpret the situation. These alternative thoughts should be based on facts and logical considerations, reducing bias;

- Evaluate feelings after thought change: After developing alternative thoughts, reassess your emotions. Compare the intensity of your emotions before and after changing your thoughts;

- Self-reflection: Assessing one’s position in the world and relationship with it. Scrutinise and relativise worldviews in detail.

Thus, a cognitive protocol is an effective technique for becoming aware of and correcting cognitive biases. Systematically identifying and revising automatic thoughts can lead to more realistic thinking in the long term.

Building Cognitive Resilience: A Holistic Defense Against Cognitive Warfare

Adopting a holistic approach is essential to comprehensively shielding oneself against an opponent’s cognitive warfare. This approach not only involves recognising and correcting cognitive biases but also enhancing emotional and mental resilience. Building such resilience fosters flexible, solution-oriented responses to new, changing, or unexpected situations.

Adopting a holistic approach is essential to comprehensively shielding oneself against an opponent’s cognitive warfare.

Several key measures should be implemented to address cognitive biases and develop long-term cognitive resilience. These measures include developing resilient systems by implementing redundant and diverse communication and information systems. Additionally, cognitive training programs can strengthen cognitive abilities and critical thinking. Finally, simulations and exercises can prepare for cognitive attacks and testing responsiveness.

As part of holistic approaches to addressing cognitive biases, two models are presented below Albert Ellis’s ABCDE Model[34] and the comprehensive Cognitive Octagon-Model© developed by Vanessa Maria Landmann.

The ABC(DE) Model

In the mid-20th century, Albert Ellis developed the ABC model (fig. 2) to explain the emergence of emotions and behaviours. He recognised that a crucial step occurs between an event and the resulting emotion: the assessment.[35]

- A – Activating Event: The initial event or situation that triggers an emotional response.

- B – Beliefs: The thoughts or beliefs about the activating event. These can be rational or irrational.

- C – Consequences: The emotional and behavioural outcomes following the beliefs. An irrational belief may lead to anxiety and avoidance behaviours.

Ellis demonstrated that human feelings are not determined by the event itself but by the evaluation of it. This insight offers a point of change: by consciously or unconsciously reassessing, one can influence emotions and reactions.

![Albert Ellis´ABC model[36]](https://tdhj.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Picture2.png)

Albert Ellis´ABC model[36]

![Illustration of the ABCDE Model in Rational Emotive Therapy by Albert Ellis[37]](https://tdhj.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Picture3.png)

Illustration of the ABCDE Model in Rational Emotive Therapy by Albert Ellis[37]

The ABCDE model, an extension of Albert Ellis’s original ABC model, is central to Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy (REBT). This model aids in cognitive restructuring by illustrating how thoughts influence emotions and behaviours. It is a therapeutic framework for challenging and changing irrational beliefs, leading to more positive outcomes.

D – Dispute: This step involves questioning and challenging irrational beliefs.

E – Effect: This represents the development of new, rational beliefs and the subsequent emotional and behavioural changes. As irrational beliefs are replaced with rational ones, the individual may feel more confident and less anxious.

The Cognitive Octagon-Model© [38]

The Cognitive Octagon-Model© developed by Vanessa Maria Landmann, offers a comprehensive, holistic approach to detecting and analysing cognitive biases, as well as developing alternative solutions and achieving metacognition and cognitive resilience. An introduction to complex matter is, for example, the simplified representation of thinking into system 1, fast thinking, and system 2, slow, rational thinking, which can detect and correct bias.[39]

The Cognitive Octagon-Model© underscores the importance of metacognition—specifically, planning, monitoring, and reflecting on one’s thinking—to effectively implement these corrections, making the metacognition system relevant.

The Cognitive Octagon-Model© initiates reflective and self-critical examination of information processing within our cognitive system.

The model consists of an outer and an inner part. The outer eight points provide an initial orientation, creating distance from the information. The description of the points starts from the top and moves clockwise, but you can start anywhere): information classification: distinguishing the degree of confidentiality (public, confidential, secret, top secret); information location: geographical coordinates related to the information’s location; information content: the specific content of the information; information purpose: the goal or desired outcome of the information; information source: the origin of the information; information direction: the direction in which the information impacts (internally, e.g., domestic population; externally, e.g., internationally); information beneficiaries: the individuals or groups who benefit from the information (“cui bono”); and finally, information Nature: the emotional assessment of the information (negative or positive).

Inside the model, four lines connect the following opposing points (the description is starting from the top and moving clockwise, but you can start anywhere): First is awareness (self-perception: where, who, how am I currently; how do I see the world and my relationship to it) versus mindfulness (bringing oneself back to the present moment); Second, taking time for fact-checking (e.g., via open sources) versus striving for objectivity (attempting to view the information as impartially as possible); Third, the relativity of perspective (e.g., two people facing each other may see a digit on the ground as either “6” or “9”; also includes tolerance of ambiguity—there is no absolute truth) versus Openness to New Perspectives; and Fourth, changing perspectives or thinking the opposite (creating distance and new viewpoints) versus Consulting Others (discussing the information with others and considering different viewpoints).

The conscious reflection and engagement with the specific points transition thinking from System 1 (fast thinking) to System 2 (slow, rational thinking), uncover cognitive biases, and create alternatives. When applying the more detailed model, neither the starting point nor the order of the inner and outer points is mandatory, leaving it up to the user. The goal is not only the transition from System 1 to System 2 through deliberate engagement but to achieve system-relevant metacognition further and develop cognitive resilience.

Manoeuvre to Achieve Cognitive Resilience

To develop cognitive resilience, one can adopt a methodical and strategic approach. This process begins with identifying mental barriers—those cognitive distortions and blockages that obstruct clear and effective thinking. Once these barriers are recognised, the next step is to analyse their causes and develop a targeted plan to address them. This analysis can be supported by self-reflection, seeking feedback, and exploring relevant literature.

Building cognitive resilience is an ongoing endeavour involving regular training and practice. Engaging consistently in activities such as mindfulness meditation, cognitive behavioural therapy, and stress management techniques helps to strengthen resilience over time. In moments of stress or challenge, applying your learned strategies helps test and further develop your cognitive resilience.

Building cognitive resilience is an ongoing endeavour involving regular training and practice.

After implementing these strategies, reflecting on the outcomes and adjusting your approach as needed is crucial. This reflective process ensures continuous improvement and adaptation. Additionally, drawing insights from various disciplines and collaborating with experts can provide valuable perspectives and enhance your methods.

By systematically following this approach, you can fortify your cognitive resilience, manage mental challenges more easily, and enhance your ability to act confidently and effectively in both personal and professional settings. In doing so, you can effectively defuse the mental “bombs” that arise, leading to a more stable and resilient mindset.

By systematically executing this manoeuvre, cognitive resilience can be sustainably strengthened, and mental “bombs” can be defused. This enables more effective and confident actions in both personal and professional life.

Vanessa Maria Landmann, former Close Protection Officer/Task Force Cobra (police tactical unit), experienced in numerous fields of economy and law enforcement such as anti-terror, crowd and riot control, immigration police, and detention centre. Interests: Consciousness research, information management, developing techniques for mental resilience and capabilities.

Bernhard Schulyok, research interests: Security Policy, Military Capability Development; earlier publications: three handbooks and numerous individual articles in the journal “Truppendienst “and online journal “The Defence Horizon Journal”; National Director of the multinational platform Military Capability Development Campaign (MCDC); academic field: Military Sciences.

The views contained in this article are the authors’ alone and do not represent the views of the Austrian Federal Ministry of Defence.

[1] Werner Stangl, Online Lexikon für Psychologie und Pädagogik, “Mäeutik – Maieutik,” https://lexikon.stangl.eu/7898/maeutik-maieutik [13.09.2024].

[2] Antonio Panovski, Aristotle’s Model of Communication: 3 Key Elements of Persuasion, last modified November 11 2023, https://www.thecollector.com/aristotle-model-communication/ [13.09.2024].

[3] Idem.

[4] Idem.

[5] Keith E. Campbell, Diane E. Oliver, Kent A. Spackman, and Edward H. Shortliffe, Representing Thoughts, Words, and Things in the UMLS, Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, Volume 5, Issue 5, September 1998, Pages 421–431, https://academic.oup.com/jamia/article/5/5/421/791796?login=false [09.09.2024]

[6] Hans Rudolf Straub, Das semiotische Dreieck, August 14, 2023, https://hrstraub.ch/das-semiotische-dreieck/ [13.09.2024].

[7] David C. Smith, De-Militarizing Language, Peace Magazine, Juli-August 1997, 14, https://peacemagazine.org/archive/v13n4p14.htm [13.09.2024].

[9] https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2021/09/02/two-decades-later-the-enduring-legacy-of-9-11/.

[10] Rodrick Wallace (2018), AI in the Real World, In: Carl von Clausewitz, the Fog-of-War, and the AI Revolution, SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology, Springer, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74633-3_1 [09.09.2024].

[11] Ibid.

[12] Kristen Gingrich, Why People Get Emotionally Triggered, Psychology Today, October 05, 2023, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/small-steps-big-changes/202310/why-people-get-emotionally-triggered [13.09.2024].

[13] Aditya Shukla, 8 Powerful Ways to Overcome Thinking Errors and Cognitive Biases, Cognition Today, August 19, 2024, last modified on May 15, 2023, https://cognitiontoday.com/8-powerful-ways-to-overcome-thinking-errors-and-cognitive-biases/ [13.09.2024].

[14] Nova Psychology, Understanding Cognitive Biases: How They Influence Our Decisions, https://novapsychology.ca/understanding-cognitive-biases-how-they-influence-our-decisions/ [13.09.2024].

[15] F.A.Z. Redaktion, Attentat auf Donald Trump: Was bisher bekannt geworden ist, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, September 12, 2023, https://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/us-wahl/attentat-auf-donald-trump-was-bisher-bekannt-geworden-ist-19864480.html [13.09.2024].

[16] B. J. Casad, and J.E. Luebering, confirmation bias, Encyclopedia Britannica, July 30, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/science/confirmation-bias [13.09.2024].

[17] Kendra Cherry, What Is the Anchoring Bias?, Verywell Mind, September 12, 2023, https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-the-anchoring-bias-2795029 [13.09.2024].

[18] Dan Pilat, Sekoul Krastev, Availability Heuristic, The Decision Lab, February 15, 2023, https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/availability-heuristic [13.09.2024].

[19] Saul McLeod, Fundamental Attribution Error, Simply Psychology, February 12, 2024. https://www.simplypsychology.org/fundamental-attribution.html [13.09.2024].

[20] Kendra Cherry, What Is Groupthink?, Verywell Mind, February 22, 2023, https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-groupthink-2795213 [13.09.2024].

[21] Dan Pilat, Sekoul Krastev, Hindsight Bias, The Decision Lab, 2024, https://dorsch.hogrefe.com/stichwort/rueckschaufehler [13.09.2024].

[22] Harbor Mental Health, How to Overcome Negativity Bias, Harbor Mental Health, November 26, 2022, https://harbormentalhealth.com/2022/11/26/how-to-overcome-negativity-bias/ [13.09.2024].

[23] Deutschlandfunk Nova, Das Attentat auf Oskar Lafontaine, (17.04.2020), Attentat: Der Messer-Angriff auf Oskar Lafontaine · Dlf Nova (deutschlandfunknova.de) (01.08.2024).

[24] Royal Australian Armoured Corps Manoeuvre Warfare Handbook, 1994, https://cove.army.gov.au/article/manoeuvre-warfare-size-doesnt-matter-its-how-you-use-it [09.04.2024]

[25] Anastasia A. Anashkina, Eleny Y. Leberfarb and Yuriy L. Orlov (2021), Recent Trends in Cancer Genomics and Bioinformatics Tools Development, International journal of molecular sciences, 22(22), 12146, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222212146 [13.09.2024].

[26] Manuela Fernández Pinto, Methodological and Cognitive Biases in Science: Issues for Current Research and Ways to Counteract Them, Perspectives on Science 2023; 31 (5): 535–554, https://doi.org/10.1162/posc_a_00589 [13.09.2024].

[27] Dorsch, Lexikon der Psychologie, Psychoneuroimmunologie, https://dorsch.hogrefe.com/stichwort/psychoneuroimmunologie [30.06.2024].

[28] Idem.

[29] Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, Cancer Neuroscience: Aktuelles aus der Forschung, Dekade gegen Krebs, 2024, https://www.dekade-gegen-krebs.de/de/krebsforschung/aktuelles-aus-der-forschung/_documents/24_CancerNeuroscience.html [13.09.2024].

[30] Idem.

[31] Idem.

[32] Idem.

[33] Lisa Stappert, Was sind kognitive Verzerrungen? Definition und Beispiele, https://blog.hubspot.de/marketing/kognitive-verzerrung, [30.06.2024].

[34] NLP-Zentrum Berlin, ABC-Modell nach Albert Ellis, NLP-Zentrum Berlin, March 24, 2013, https://nlp-zentrum-berlin.de/infothek/nlp-psychologie-blog/item/abc-modell-albert-ellis [13.09.2024].

[35] Idem.

[36] NLP-Zentrum Berlin, ABC-Spirale, March 24, 2013, https://nlp-zentrum-berlin.de/storage/2023/04/ABC-Spirale.png [13.09.2024].

[37] Alexander Nusselt, Verhaltenstherapie, Nusselt, June 01, 2023, https://nusselt.de/verhaltenstherapie/ [13.09.2024].

[38] Copyright Vanessa Maria Landmann, 2024. All rights reserved.

[39] Johann Sjuts: Schnelles Denken, langsames Denken und die Systemrelevanz von Metakognition, https://www.math.uni-osnabrueck.de/fileadmin/didaktik/Publikationen/Sjuts/Sjuts_Johann_Metakognition_MNU_01-2021_54-61.pdf (01.08.2024).