Abstract: This paper seeks to highlight the underlying security issues of the 2016 FARC Peace Accord, and the road that lies ahead. By understanding the initial goals of the peace process, we will be able to better understand the issues it is currently facing and how the accords have failed to achieve even some of their most basic promises. One of the most significant issues has been the safety and security of Colombians, especially in women’s and LGBTQ communities. The government needs to do a better job of reintegrating former FARC members and providing sustainable safety nets so these former members do not relapse back into violence.

Problem statement: How to provide social and cultural integration for some of the most at-risk individuals in Colombia?

Bottom-line-up-front: Ultimately failing the Colombian people, the Colombian Government has piecemealed the Peace Accords together without sustaining long-term positive and tangible results. Failure to reintegrate former FARC members into society and provide social safety nets, the government has put these men, women, and children at even greater risk of violence and domestic abuse and largely left them to their own devices.

So what?: The US, UN, and outside observers should have taken greater steps to ensure the Accords were being upheld at every level of implementation. Leaving the Colombian Government to taper off its promises has resulted in an even greater period of violence and bloodshed in an already traumatized nation.

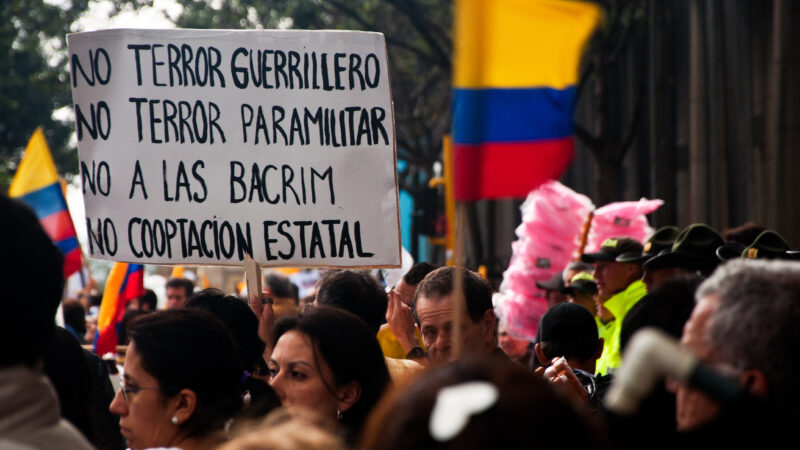

Source: shutterstock.com/Jess Kraft

The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia

The Central and South American regions have been plagued by several critical issues in recent decades, including corrupt government institutions and leaders, cartels, narcotics, external influences, and crippling debt. Colombia, in particular, has seen most of, if not all, of the above issues coincide with one of the world’s most notorious guerrilla groups, The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), which emerged in the 1960s as a Marxist guerrilla group fighting Colombia’s elites. Attempting to tackle the equity issue that the nation has been battling for centuries, the FARC fought the Colombian government, engaging in drug smuggling, human trafficking, and subversion.

Fast forward to the 2016 Peace Accords, when the world cheered as the Colombian government and the FARC came to a ceasefire agreement. The guerrilla group agreed to put down their arms, relinquishing them to UN Peacekeepers, and relocating to other regions of the country to pick up everyday civilian lives. The Colombian government promised protection and help with this transition for the former group members, agreeing to equip the FARC with a legitimate political voice and identity through 10 seats in Congress. Between the first round of talks held in Havana in 2012 to the official signing of the General Agreement to End the Armed Conflict and Build a Stable and Lasting Peace (“Peace Accord/Accord”) in 2016, were more than 50 rounds of negotiations, and one failed peace deal that was voted down in October of 2016. The Accord was signed between the National Government of Colombia, and the FARC, as delegates from the Republic of Cuba and Norway served as witnesses.

The Colombian government promised protection and help with this transition for the former group members, agreeing to equip the FARC with a legitimate political voice and identity through 10 seats in Congress.

Additionally, the University of Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (Kroc) was enlisted to monitor and verify the extent of the peace process and its success. Kroc has been instrumental in keeping accurate and unbiased records of the implementation of the Peace Accord. Kroc, professors, and researchers developed the Peace Accord Matrix to ensure that all aspects of the agreement were being complied with and implemented.

The Kroc Report

Within the actual text of the Peace Accord, Kroc was slated to “…gather and assess implementation events from published sources and field observations from a Colombia-based team of peace process specialists….and to produce monthly data and periodic reports on the status of implementation.”(Section 6.3.2)[1] According to the Fourth Kroc Report[2], three years after the signing of the Accord, there was still a significant gap between the planned implementation of measures focusing on gender and ethnic inclusion and reality. The Fifth and Sixth Kroc Reports[3] highlight that while Points 3 and 6 of the Accords (End of Conflict and Infrastructure Implementation) were rapidly completed, the majority of the rest of the Points are sitting in minimum to intermediate levels of completeness. The Kroc research shows that for the Colombian Government to fully reach the most impacted communities formerly under FARC control, it must work with ethnic communities and minorities to implement its policies.

One of the largest issues has been the safety and security of community members, especially in women’s and LGBTQ communities. The government needs to better protect these groups from retaliation from ex-guerrilla members and violence from the new paramilitary and gangs that have filled the void left by the FARC. In Colombia, the strong Catholic majority gives way to prejudice and discrimination against the LGBTQ community. According to the Fourth Kroc report[4], 2019 was the most violent year since the signing of the Accords, with an increase of 18.5% in homicides, chiefly against ex-combatants. Traditional family values in Colombia, reinforced by the Catholic majority, seemed to be at risk with the signing of the Accord; many religious and conservative groups in the country pressured the Colombian government to abandon its efforts to adopt a policy to legalize same-sex marriage as well as grant adoption rights to these couples. While Colombia has some of the strongest legal frameworks and protections for LGBTQ+ people on paper as a result of the Peace Accords, in practice, it is vastly different. In a 2020 study[5], Colombia registered the highest number of killings of LGBTQ+ people in the last five years, and between 2014-2019 over 30% of homicides in the nation were the result of prejudice. Data reported[6] from SinViolencia LGBT account for over 1,100 homicides of gay and trans Colombians.

While Colombia has some of the strongest legal frameworks and protections for LGBTQ+ people on paper as a result of the Peace Accords, in practice, it is vastly different.

According to an article by Juan Arredondo[7], since 2016, around 700 community leaders have been killed, with most of these murders taking place in regions that the FARC had previously controlled. This signifies that the government has failed to properly establish its presence in these regions, leaving the void to be filled by other groups. These communities should have been some of the first to see government intervention through infrastructure development, schools, sanitation, or any other promises made in the Accord. While it is easy for the international community to blame President Duque and his administration for these failures to intervene appropriately, it should be pointed out that providing necessities such as electricity and sanitation to some of the most remote regions of the country takes a lot more than five years. The slow rollout of many facets of the Accord is the result of stagnating support for some of the policies. As mentioned earlier, conservative political and community leaders across the country have made it hard to agree on some small text in the agreement. Another fact is that at the local level, political leaders are plagued by corruption that sees funds diverted, policies shot down, and cartel members puppeteering various regions. Cracking down on corruption in the country would enable aspects of the Accord to be integrated more efficiently. Points 3 and 4, for instance, target the reincorporation of FARC members into civilian life and combating criminal organizations. With high levels of localized corruption, former combatants will never be protected at the local level as they try to re-integrate into society.

Colombia’s Comprehensive Rural Reform

Even some efforts which started off strong as part of the Accord have been since neglected, to disastrous effect. Another initiative that was initially seen at the crux of the Accord was the Comprehensive Rural Reform (RRI), essentially a land redistribution program. It sought to redistribute the land taken from the FARC and give it back to citizens for multipurpose development. The Accord believed that within the first decade, RRI would be able to grant over three million hectares of land to Colombians. As of August 03, 2020, Kroc Report, a little over one million hectares were reassigned to farmers, including 327,000 rural women. Part of the RRI initiative was also supposed to be geared towards cash subsidies to coca farmers. Essentially, if farmers destroyed their illegal coca plants and began harvesting legal crops, the government would offer cash to assist and pay farmers for these crops. In addition to legal crops paid for by the government, transport would improve, as many trade routes have already been developed thanks to the coca production and additional cash payments. As could be assumed, these cash subsidies dried up, as did many of the government promises, and many of these farmers have returned to the lucrative coca business.

If farmers destroyed their illegal coca plants and began harvesting legal crops, the government would offer cash to assist and pay farmers for these crops.

Point Four of the Accord centers around the coca industry and the drug problem the nation faces. As of 2019,[8] only 6% of the Governments programs for substitution of illicit-use crops had been completed. These programs were targeted at coca farmers and intended to see them switch from coca to a government-subsidized market of legal crops. Within the same data set, public health and drug prevention programs had no percentage of completeness, with 56% of these programs having failed even to start. As mentioned time and time again in this piece, the government’s failure to roll out policies and programs that give ex-combatants and civilians who were reliant on the FARC drug trade a way out of that life has doomed the country.

Source: shutterstock.com/F.A. Alba

A Neglected Main Effort?

The issue is that the Government has focused too much on the ceasefire agreement and less on the other aspects of the Accords. One of the most striking data points that the Kroc Report[9] highlights is that the main point of the Accords was the ceasefire and abandonment of the arms agreement, which, as of 2019, was about 97% complete. This demonstrates a huge success in removing arms from former guerrilla members and an overall agreement to the abandonment of arms. The same Kroc Report shows that only 14% of the safety guarantees had been completed, with around 70% of these guarantees not even initiated. Many ex-combatants are returning to arms and breaking from traditional FARC group as they feel the government has left them out to dry. The larger, more salient point is that irrespective of the government’s promises, the entire Accord is at risk of backsliding if it fails to hold up its end of the bargain. Weapons and arms are easy to come by, and the government’s praise of this part of the Accord should be considered a false-positive rather than a secured win.

Many ex-combatants are returning to arms and breaking from traditional FARC group as they feel the government has left them out to dry.

According to a Washington Post[10] article, some believe that President Duque’s right-wing administration is the main culprit for the lack of progress made on the Peace Accord, calling on the Biden Administration to show a stronger will and moral obligation to answer the call to uphold the agreement. Only through external pressure will the Duque administration begin to take their own Accord seriously. UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet has pleaded several times for the Colombian Government to do something about the rise in murders of prominent social activists. However, it will require more international pressure. The US is in a prime position to employ its economic strength in the hopes of pressuring President Duque to listen.

Yet, even if the Accords were properly implemented and promises kept, the agreement’s inherent shortcomings could jeopardize its success. Civilians initially voted down the 2016 peace agreement, only to be overturned by a Congressional decision; the initial rejection highlights Colombians’ many issues with the Accords. One of their biggest qualms is that by offering amnesty to ex-combatants and only seeking jail time for a handful of top-level commanders, most Colombians will have no choice but to sit and watch as their loved ones’ killers, torturers, and kidnappers go free. Due to vague wording, the agreement grants amnesty to any of those ex-combatants who take the stand and speak openly about their time with the FARC. Essentially, the government is seeking to understand the scope of the group’s work and connectivity throughout the country without blaming anyone. This creates conditions by which civilians feel they must take justice into their own hands. Since the early 2000s, several paramilitary groups have been created in an attempt to take governance into their own hands since the military and government could not be trusted. Despite the peace agreement, many of these militant groups still seek retribution against former FARC members.

One of their biggest qualms is that by offering amnesty to ex-combatants and only seeking jail time for a handful of top-level commanders, most Colombians will have no choice but to sit and watch as their loved ones’ killers, torturers, and kidnappers go free.

The underlying security issues stem from improper governance, corruption, and inequality that has plagued Colombia for centuries – and an Accord cannot solve these with the FARC alone. The disarmament of the FARC is a necessary first step. Still, as we have seen, for the peace agreement not to risk backsliding, the Accord must put the tangible benefits of victims first, rather than perpetrators. The government should seek to retake the rural and impoverished regions that the FARC has relinquished control of. Seeking to improve even the most basic qualities of life would result in a more substantial, more viable government presence in places where gangs and militant groups now control.

The Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (DDR) plan that the Colombian Government has sought to expand across the country has largely failed. What was initially seen as a win (i.e., the relinquishing of arms to UN Peacekeepers) has now proven to not even scrape the surface of the justice that the Colombian people deserve. Failing to address the equity issue and failing to deliver on several of the most basic promises of the agreement, the Duque administration now is at serious risk of the Accord backsliding into utter chaos.

A Global Security Policy with Regional Impact

Between 2000 to 2015, the US gave Colombia around $10 billion in aid, but during the Trump administration, aid and efforts dwindled. Through US military assistance, the FARC was pushed to the nation’s periphery and saw much of its usual staple peasant support begin to fade. This decrease in rural support, mixed with US military assistance, showed that the FARC narco-industrial complex could have been feasibly dealt with. Illegal mining and extortion were obviously fueling the fire, but the real interests lie in the cocaine business. One of the main reasons for the US intervention in the first place was the premise of destabilizing one of the largest drug industries plaguing the US. The Biden administration now has a pivotal decision to make. The right one would be to ramp up efforts in counterintelligence to decrease the flow of narcotics in and out of the country and give aid and guidance to the rural reconstruction programs. US security policy is also a global security policy. While it is true that the responsibility lies with the Colombian Government and people, at the end of the day, the US is in a strong position to levy future economic aid and assistance in return for current policy. Cracking down on corruption as part of the terms for sanctions and economic aid would be a wise move from the US. Allowing outside spectators to administer the Accords implementation was a great first step, but as we have seen, it is not enough to talk the talk. The US and the UN could attempt to have a greater impact by offering technical know-how and engineering expertise in terms of infrastructure building and capacity.

US security policy is also a global security policy. While it is true that the responsibility lies with the Colombian Government and people, at the end of the day, the US is in a strong position to levy future economic aid and assistance in return for current policy.

If the government truly wants to see progress, they need to set one thing straight. They need to clarify to the Colombian people that they are prepared and capable of offering solutions that the FARC and other criminal organizations cannot. The FARC became so popular because they created a sense of order in places the government had little to no control. Before it became all about coca and money, the group sought to spurn base-level change in the country through its Marxist ideology of equality. Now, in the vacuum left by the FARC, other groups and gangs have taken hold of these regions. By cracking down on local corruption and building baseline infrastructure for fundamental human rights, the government could regain a foothold in rural parts of the country. Failing to deliver on the social welfare and development promises, such as access to education, sanitation, and clean water as initially promised in the Accord, will risk greater backsliding and chaos.

Andrew R. Arlotto; Foreign Policy, Latin American Studies, Security Studies, Climate Security; Climate Control: The Case of Chilean Destabilization; Global and International Studies.The views contained in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of Finnegan LLP or George Mason University.

[1] “FINAL AGREEMENT TO END THE ARMED CONFLICT AND BUILD A STABLE AND LASTING PEACE,” National Political Agreement, The National Government of Colombia, November 24, 2016, 223.

[2] Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, “Report Four – Point by Point: The Status of Peace Agreement Implementation in Colombia,” University of Notre Dame Keough School of Global Affairs, August 3, 2020.

[3] Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, “Five Years of Peace Agreement Implementation in Colombia: Achievements, Challenges, and Opportunities to Increase Implementation Levels,” University of Notre Dame Keough School of Global Affairs, December 2016-October 2021, https://doi.org/10.7274/0c483j36025 and Echavarría Álvarez, Josefina, et al, Executive Summary, Five Years After the Signing of the Colombian Final Agreement: Reflections from Implementation Monitoring, Notre Dame, IN: Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies/Keough School of Global Affairs, 2022, https://doi.org/10.7274/0z708w35p43.

[4] Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, “Report Four – Point by Point: The Status of Peace Agreement Implementation in Colombia,” University of Notre Dame Keough School of Global Affairs, August 3, 2020, 16, http://peaceaccords.nd.edu/fourthreport.

[5] “EL PREJUICIO NO CONOCE FRONTERAS: Homicidios de lesbianas, gay, bisexuales, trans en países de América Latina y el Caribe 2014-2019,” SinViolencia LGBT, August 2019, www.sinviolencia.lgbt.

[6] Ibid., 27.

[7] Juan Arrendondo, “The Slow Death of Colombia’s Peace Movement,” The Atlantic Magazine, December 30, 2019.

[8] Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, “Report Four – Point by Point: The Status of Peace Agreement Implementation in Colombia,” University of Notre Dame Keough School of Global Affairs, August 3, 2020, 20.

[9] Ibid., 17.

[10] Hanna Wallis, “Colombia’s Failing Peace Process Is Killing Social Leaders. The U.S. Must Help Revive It,” The Washington Post, March 2, 2021.