Abstract: Information Warfare and Influence Operations (IW/IO) are offensive tools in countering state and non-state disinformation. If applied in the context of statecraft, IW/IO can be an offensive deterrence strategy to any would-be adversary. Evidence suggests the shortcomings of traditional public affairs/public relations campaigns. Dealing with a large body of data of adversarial disinformation, we must embrace the non-linear, non-symmetric approach to Information Warfare and Influence Operations (IW/IO). An urgent need for intellectual innovation, resources, and resourcefulness, technology and drawing from the rich tapestry of the history of Information and Influence Operations (IIO) is underutilized. This paper adds to the growing number of voices warning policymakers of falling into a pattern of predictability of traditional but flawed manual-like responses.

Bottom-line-up-front: The Information Warfare and Influence Operations’ historical records show consistently a determined campaign influences political, economic, and social outcomes. The European Union should create a more sustainable strategic Information and Influence Operation concept beyond the tactical or only military application. This requires resources, skills, out-of-the-box approaches beyond a limited accounting cycle and should not be mistaken with PR campaigns to get ahead in the battle of ideas.

Problem statement: How to assess and understand the need to transition research on Information Warfare from “problem stating” to holistic solutions in the policy space and a strategic context?

So what?: Russian disinformation practice is as valid today as it was three decades ago. And like during the height of communism, the threat was initially under-estimated in the early 2000’s. Disinformation remains a recognized threat to the domestic and external stability of the European Union and its allies. Little has changed to curtail or defeat hostile adversarial actions. Institutional knowledge was lost despite Information Warfare and Influence Operations being part of legitimate statecraft and requiring a non-traditional, non-linear process, innovative thinkers, hands-on operational experience, and expertise to apply a forward-leaning approach to protect our societies.

Source: Pixabay.com/TheAndrasBarta

World War III is a guerrilla information war with no division between military and civilian participation

(Marshall McLuhan, 1970)

Information Warfare and Influence Operations (IW/IO) are the current axioms in the strategic and policy spaces within the European Union Security and Defense realm. Routinely featured in the European Union, NATO, and the United States debates, it is neither the question of policy or technology but the absence of expedient operational flexibility, innovational approaches to counter adversarial disinformation or influence operation. The European Union consistently shows a haphazard, overly bureaucratic, and administratively burdensome[1] response. Speed, agility, and volume is the coinage of Information and Influence Operations.

This paper critically addresses this complex topic with the view of recognizing that Information and Influence Operations play in today’s political, social, and economic landscape[2]. However, all parties agree that the topic is neither new nor revolutionary[3]. It is part of genuine statecraft[4] committed by all actors. Yet, the digital revolution raised the stakes. Research shows a 150% increase in social media manipulation campaigns since 2017 underscores the critical nature[5]. Research shows that China is estimated to employ between 300,000 to 2,000,000 people working in disinformation. The counter forces are rather thinly spread[6]. This paper aims to trigger a perhaps more forward-leaning outlook while engaging in Information or Influence Operations as a discipline within the European Union national security framework.

The Costs of the Rough End of Soft Power

In particular, the impact of Information Operations on the economy, a pillar for the European Union, is seldom addressed. Whereas economic warfare is part of US strategy, the European Union continues to hold a somewhat archaic view on the implications of hostile Information Operations. Economic impacts such as the weaponization of energy and “collaboration of suitable economic, business and political projects” go beyond Russia and Chinese interests[7]. A 2019 economic study revealed that disinformation costs the global economy annually $78 billion[8]. The UK House of Common 2019 report added $39 billion losses every year due to disinformation[9].

The figures must concern us. Investments in the Information and Influence Operations measures pales compared to the losses the European and its allies suffer. The 2019 Oxford university study also shows a consistent growth of the global disinformation campaigns[10], [11] regardless of the policies efforts by European Union. The study identified at least 70 countries engaged in political disinformation campaigns demonstrating the popularity of disinformation. Consequently, the IIO’s response needs to be viewed with a strategic rationale. Paul Stockton, in a 2021 study, wrote, “But today’s IOs differ from the coercive pressures that the United States could face in an edge-of-war confrontation in the South China Sea, the Baltics, or other potential conflict zones. Coercion relies on threats of punishment to convince an adversary to yield in a crisis”[12]. But disinformation campaigns go beyond the political realm and requires the intellectual depth to understand the complexities of the Russian and Chinese disinformation and counter-information “game”.

The lack of innovation and comprehension by the policy and business community leaders is staggering. Almost none of the business community is engaged in Information Operations, left to the government, although the business community is routinely a victim of disinformation campaigns[13]. One aspect of disinformation operations is the very tangible outcome of losing market share or market space denial[14]. Hence, Information Operations cascades throughout the social fabric of the state, business[15] and society[16] if applied as an offensive response to adversaries. It warrants a more in-depth examination of the impacts of Information Operations in support of economic warfare.

Developing an offensive capability is a logical choice of improving the toolbox of the European Union and within the state-norm to protect the interests of the European Union. However, Influence Operations are inherently an offensive tool and should be used as such.

China’s emerging as a powerful[17] force in the global disinformation landscape is considered one of the most significant developments of the past years[18]. Operating beyond the traditional realm of Chinese territories, Chinese influence operations surface in the Balkans, Africa and elsewhere. Like Russian, Iranian, Turkish, and other interests, it is imperative that Europe’s defensive capabilities are rapidly bolstered.

Developing an offensive capability is a logical choice of improving the toolbox of the European Union and within the state-norm to protect the interests of the European Union.

The Threat Never Vanished

Despite the development of highly detailed EU policies, think-tank papers, technology initiatives, conferences of experts in hybrid and asymmetrical warfare, semi-hysterical responses by mainly western media outlets[19], ‘old-hands’ of the cold war days snuggle at the suddenly revived interest in adversarial disinformation. A certain ‘Schadenfreude’ of we-told-you-so circulates within the small community of old hands. For the now older generation of counter-information/-propaganda operations experts, the threat had never vanished despite the Soviet Union’s collapse thirty years ago. It continues to evolve, metastasize, and adopt[20], utilizing technology and political support with ease and great success. In contrast to Europe and the United States, active measures are part and parcel of Russian and Chinese doctrine. Increasingly adopted by newer actors such as Iran, Turkey, and extremists’ movements such as the Taliban and non-state actors, the Europeans have considerable room for improvements.

For the now older generation of counter-information/-propaganda operations experts, the threat had never vanished despite the Soviet Union’s collapse thirty years ago.

The US, and particularly the Europeans, still struggle and engage in knee-jerk reactions[21], semi-panic political (ab)-sense of leadership given the adversaries almost mythical, perceived powers of Information Warfare/Information Operations aimed to influence western policy[22]. Ukraine[23], Crimea[24], South China Sea[25], Afghanistan, the Western Balkans[26] and Africa[27] are sufficient examples of how the various actors successfully applied Information Warfare. Some literature argues that the absence of rigor fails to recognize the diversity of mis- and disinformation, its forms, motivation, and dissemination[28]. In particular, the process of ideological ‘redpilling’, feeds the public distrust contributing to the radicalization of societies[29]. With the digital landscape, traditional approaches are insufficient to counter the massive volume of hostile actors.

Viewed from the sidelines, the European Union was caught sleeping, responded sluggish and slow with a predictable response. The Brookings Institute wrote, “The EU’s attempt to share information and spot trends through an early-warning system about Russian propaganda has produced no alerts and is struggling to be relevant”[30].

In its response, the almost linear, bureaucratic approaches by the European Union make the counter-information actions predictable and therefore limited in effectiveness with the targeted audiences. Judy Dempsey wrote that the Russian disinformation campaigns are systematic, well resourced, and perpetrated on a large scale than similar campaigns including China, Iran, and North Korea[31]. Watts and Rothschild provide some sense of the colossal size of disinformation facing democracies[32].

One of the trademarks of Information Operation is fluidity and rapid responses, not necessarily the grammatically accurate representation of facts. For mass mobilization, negative influence, as seen in Hong Kong, speed matters over the accuracy of narratives. Today some argue that notions of propaganda aptly describe the contemporary information campaigns conducted by many activists[33]. Therefore, any counter-response demands to go beyond one-dimensionality-tit-for-tat strategies. It is a flaw of the western approaches to Information Warfare that attempts to achieve perfection in response, missing the emotional issues surrounding disinformation/counter information. In the digital space speed, imperfection, and volume matter.

For the now older generation of counter-information/-propaganda operations experts, the threat had never vanished despite the Soviet Union’s collapse thirty years ago.

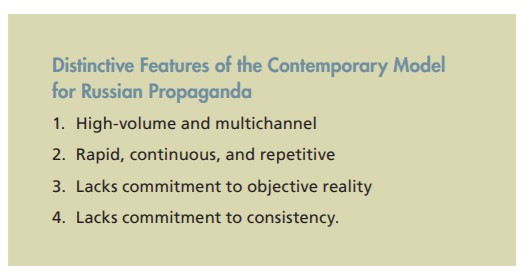

RAND, The Russian “Firehose of Falsehood” Propaganda Model

Information Operations targeted audience can be summarized as: a) the public, b) incapacitating or paralyzing the leadership, c) influencing the military and d) influencing political decision making. Creating fear and panic causing distrust in the population is the strategic objective. Influence and Information Operation provide the fertilizer to tip behavior of adversaries as a cost-effective alternative[34]. Although undoubtedly relevant, quantity over quality is a constant misperception held by the high powers of Information Operation. The RAND study wrote, “Russian propaganda is produced in incredibly large volumes and is broadcast or otherwise distributed via a large number of channels. This propaganda includes text, video, audio, and still imagery… propagated via the Internet, social media, satellite television, and traditional radio and television broadcasting…. The channel [RT] is particularly popular online, where it claims more than a billion page views. If true, that would make it the most-watched news source on the Internet. ….In addition to acknowledged Russian sources like RT, there are dozens of proxy news sites presenting Russian propaganda, but with their affiliation with Russia disguised or downplayed”.[35]

In the Counter-intelligence ecosphere of Information Operation, one of the dead-giveaways is the attempt to prove in chapter and verse, preferably with hyperlinks, the falsehood of the argument, submitted to the academic, legal, moral, and other rigor of the response. However, it misses the audience, their interests, and their concern. By the time the counter-narrative is responded to, the digital world of disinformation has moved on, the audience rolled their eyes, and the narrative is lost in the tsunami-like volume what a RAND study called the Russian “Firehose of Falsehood”[36]of daily misinformation by the adversaries. Research suggests that all other things being equal, messages received in greater volume and from more sources will be more persuasive. Quantity does indeed have a Quality of its own. Volume does matter[37].

…In an information environment characterized by high volumes of information and limited levels of user attention and trust, the tools and techniques of computational propaganda are becoming a common – and arguably essential – part of digital campaigning and public diplomacy….

Whereas World War Two and the Cold War has a long history in countering disinformation after the collapse of the Soviet Union, thirty years ago, both institutional knowledge and skills were relegated to the dusty archives of history. By 1992, the cold warriors countering Soviet propaganda were retired, their experiences boxed up and archived. Institutional knowledge, personnel, linguistic and operational knowledge was lost and largely forgotten. Brian Raymond argued that the United States and the European Union needs a Counter-Disinformation strategy and cold war era tactics are not enough[38].

With the rise of Russia and China,[39] the political propaganda saw an equal adaptation by Islamic State, the Taliban, and other extremists. By 2014/15, the return of propaganda was seen in the false stories of the Polish president insisting on Ukraine to return former Polish territory, or the Islamic State joining pro-Ukrainian forces, to name a few. Information Warfare/Influence Operations is a first-strike option supporting military operations. Hence the absence of a counter-information program creates a political vacuum that could lead to misjudgment by the adversaries.

With Islamic State for the first time, we saw a dramatic shift in Information Operations. In the case of Afghanistan[40], similar efforts were underway[41], but once more, political shortsightedness within the policy decision-makers, the absence of strategic and political consistency created ambiguity and the absence of strategic (not to be confused with tactical) direction. Emerson Brooking illustrates that a strategic counter-ideology strategy is needed and that the Taliban has waged-and now won- a singular, focused, twenty-year information war. Taliban has clearly articulated the purpose of its regime[42]. In the broader context of Europe’s need for an Information warfare strategy, the west has no such purpose.

Back to the Roots!

Not so for the strategic competitors of the European Union. Information Warfare and Influence Operations are integral parts of Russian and Chinese, Turkish, Iranian, and other political interests. Although claimed by the United States as a ‘policy of the weak’[43], [44], [45], it is an oversimplification and disregards the strategic comprehension by western interpretation of adversarial Information Operation.

It represents a policy of hubris adopting this view by the European Union, NATO, and the United States, given the significant contribution by the Double Cross System, also known as the “XX”-system by the Twenty Committee to defeat Nazi-Germany. Forgotten or largely unknown in Europe are the works of Too Chee Chew, better known as CC Too, who was a major exponent of Information Operations in countering the communist threat in Malaya. His psychological warfare section was responsible for many of the tactics and innovations even in use today.

Forgotten or largely unknown in Europe are the works of Too Chee Chew, better known as CC Too, who was a major exponent of Information Operations in countering the communist threat in Malaya.

More important, CC Too was a research assistant, a teacher, but an avid reader of the enemy’s propaganda. He had no military training, nor was he a battle-hardened veteran who bore arms. He was a reader of the adversary’s narrative. The works of CC Too Psychological Warfare Section are overlooked by the shallow interpretation of what constitutes the space of today’s counter-information campaigns, often applied as an extension of a military campaign rather than a comprehensive all-out effort of governments. Other examples show, “Mattis told the committee that CENTCOM lawyers had determined the activities were “strictly within the guidelines of the law” and that “in today’s changing world, these are now traditional military activities. They’re no longer something that can only be handled by Voice of America or someone like that.” …. In this environment, it is difficult to pass down a coherent IO [information operations] plan from the strategic to the tactical level. Each geographic location is unique.”[46]

Other more contemporary examples such as the Gulf War in the 1990s or Operation Earnest Voice (OEV) in Iraq first deployed against Al Qaeda with a 200 million USD budget, but by 2011 the program was still ‘experimenting’, making a point of a cohesive strategy was absent. The program focused on old, mainstream, TV and radio transmissions and public-affairs blogging[47]. On the other hand, in 2002, the Taliban activated its media arm and used Facebook, WhatsApp, and other live feed media. For example, far-left extremists in Australia linked to Indonesians residing in Hong Kong were linked to the Kalifate of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan as early as 2010 through a Facebook account.

In areas with low interconnectivity, illiteracy, mainstream broadcasting of a narrative will need non-traditional distribution channels to reach the hinterlands of the Western Balkans, depths of Africa or other regions of interest. In the global Information and Influence Operation landscape, the battlespace is not geographical limited to physical borders in Europe. Battles over Turkey are fought in Qatar, Azerbaijan, or Kazakhstan. Once more, large volume matters.

Despite the historical successes, the European Union views IW/IO as an after-thought, often defensive or reactive (“tit-for-tat”) response rather than a sustained strategy. Although hybrid threats are seen as a threat to the external and internal stability of the European Union, the counter strategies are ambiguous and often fragmented responses. An organizational and cultural transformation of the European Union policy is needed. One aspect is clear: Information Warfare and Influence Operations are here to stay.

Marc Dubois, specializes in operating counter disinformation campaigns, lectures on the subjects such as counter-terrorism, far-left extremists, fringe radicals, intelligence reform, radicalization of society, disinformation operations by non-state actors. The views contained in this article are the authors alone.

[1] European Parliament, Russia’s disinformation on Ukraine and the EU’s response, November 2017, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2015/571339/EPRS_BRI(2015)571339_EN.pdf, accessed on 12 October 2021.

[2] U.S. Committee on Foreign Relations U.S. Senate, 10 January 2018; https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/FinalRR.pdf, 2, accessed on 13 October 2021.

[3] Hossein Derakshan, Claire Wardle, Annenberg School for Communications 15-16 December 2017, Understanding and Addressing the Disinformation Ecosystem, https://firstdraftnews.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/The-Disinformation-Ecosystem-20180207-v4.pdf, 7, accessed on 11 October 2021.

[4] Julie Posetti, Alice Matthews, A short guide to the history of ‘fake news’ and disinformation, 23 July 2018, https://www.icfj.org/sites/default/files/2018-07/A%20Short%20Guide%20to%20History%20of%20Fake%20News%20and%20Disinformation_ICFJ%20Final.pdf, accessed on 14 October 2021.

[5] Chris Delatorre, Digital Impact, Computational Propaganda and the Global Disinformation Order, 22 October 2020, https://digitalimpact.io/report-roundup-03-computational-propaganda-disinformation-order/, accessed on 23 October 2021.

[6] Ibid., 18.

[7] European Think-tank Network on China (ETNC), China’s Soft Power in Europe Falling on Hard Times, April 2021, https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2021-04/Report_ETNC_Chinas_Soft_Power_in_Europe_Falling_on_Hard_Times_2021.pdf, accessed on 20 October 2021.

[8] Eillen Brown, Online fake news is costing us $78 billion globally each year, 18 December 2019, https://www.zdnet.com/article/online-fake-news-costing-us-78-billion-globally-each-year/; accessed on 10 October 2021.

[9] House of Commons (UK) Eight Report of Session 2017-2019, Disinformation and ‘fake news’: Final Report 14 February 2019, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmcumeds/1791/1791.pdf, accessed on 13 October 2021.

[10] Chris Delatorre, Digital Impact, Computational Propaganda and the Global Disinformation Order, 22 October 2020, https://digitalimpact.io/report-roundup-03-computational-propaganda-disinformation-order/, accessed on 23 October 2021.

[11] Samantha Bradshaw, Philip N. Howard, Oxford University, The Global Disinformation Order, 2019 Global Inventory of Organised Social Media Manipulation, https://demtech.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/93/2019/09/CyberTroop-Report19.pdf, accessed on 23 October 2021.

[12] Paul Stockton, John Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, Defeating Coercive Information Operations in Future Crisis, 2021, https://www.jhuapl.edu/Content/documents/DefeatingCoerciveIOs.pdf, accessed on 11 October 2021.

[13] Lyric Jain, Fast Company, Disinformation is emerging as a threat to businesses, 5 October 2021, https://www.fastcompany.com/90633225/disinformation-threat-business; accessed on 20 October 2021.

[14] Caroline Binham, Financial Times, Companies fear rise of fake news and social media rumours, 30 September 2019, https://www.ft.com/content/4241a2f6-e080-11e9-9743-db5a370481bc, accessed on 19 October 2021.

[15] Claire Atkinson, NBC News, Fake news can cause ‘irreversible damage’ to companies – and sink their stock price, 26 April 2019, https://www.nbcnews.com/business/business-news/fake-news-can-cause-irreversible-damage-companies-sink-their-stock-n995436, accessed on 21 October 2021.

[16] U.S. Committee on Foreign Relations U.S. Senate, Putin’s Asymmetric Assault on Democracy in Russia and Europe: Implicatons for U.S. National Security, 10 January 2018, https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/FinalRR.pdf, 2, accessed on 13 October 2021.

[17] In Frank/Vogl (eds.): China’s Footprint in Strategic Spaces of the European Union. New Challenges for a Multi-dimensional EU-China Strategy, Schriftenreihe der Landesverteidigungsakademie No. 11/2021, https://www.bundesheer.at/pdf_pool/publikationen/book_chinas_footprint_05_chinas_narratives_hybrid_threats.pdf, accessed on 29 October 2021.

[18] Davey Alba, Adam Satariano, The New York Times, At Least 70 Countries Have Had Disinformation Campaigns, Study Finds, 26 September 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/26/technology/government-disinformation-cyber-troops.html, accessed on 25 October 2021.

[19] Reid Standish, Why Is Finland Able to Fend Off Putin’s Information War? Foreign Policy 1 March 2017, https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/01/why-is-finland-able-to-fend-off-putins-information-war/, accessed on 12 October 2021; …..Elsewhere in the Baltics and former Soviet Union, Russian-linked disinformation has worked to stoke panic and force local governments into knee-jerk, counterproductive responses that have boosted Kremlin goals across the region….

[20] Margaret L. Taylor, Combating disinformation and foreign interference in Democracies: Lessons from Europe, 31 July 2019, Brookings Institute, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2019/07/31/combating-disinformation-and-foreign-interference-in-democracies-lessons-from-europe/, accessed on 14 October 2021.

[21] Reid Standish, Why Is Finland Able to Fend Off Putin’s Information War? Foreign Policy 1 March 2017, https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/01/why-is-finland-able-to-fend-off-putins-information-war/, 57, accessed on 12 October 2021.

[22] Duncan Allan and et.al.; Myths ad misconceptions in the debate on Russia. May 2021, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2021-05/2021-05-13-myths-misconceptions-debate-russia-nixey-et-al.pdf, accessed on 10 October 2021.

[23] Ibid., 70.

[24] Ibid., 75.

[25] Dexter Roberts, Atlantic Council, China’s Disinformation Strategy, December 2020, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/CHINA-ASI-Report-FINAL-1.pdf, accessed on 19 October 2021.

[26] Jelena Jevtić, Security Distellery, The Russian Disinformation Campaign in the Western Balkans, 28 April 2021, https://thesecuritydistillery.org/all-articles/the-russian-disinformation-campaign-in-the-western-balkans, accessed on 14 October 2021.

[27] Pierre Morcos, CSIS, NATO’s Pivot to China: A Challenging Path; 8 June 2021, https://www.csis.org/analysis/natos-pivot-china-challenging-path, accessed on 21 October 2021.

[28] Annenberg School for Communications 15-16 December 2017, Understanding and Addressing the Disinformation Ecosystem, https://firstdraftnews.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/The-Disinformation-Ecosystem-20180207-v4.pdf, accessed on 11 October 2021.

[29] Ibid. , Lewis, Marwick, 18.

[30] Margaret L. Taylor, Combating disinformation and foreign interference in Democracies: Lessons from Europe, Brookings Institute, 31 July 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2019/07/31/combating-disinformation-and-foreign-interference-in-democracies-lessons-from-europe/, accessed on 14 October 2021.

[31] Agnieszka Legucka, Russia’s Long-Term Campaign of Disinformation in Europe, Carnegie Europe, 19 March 2020, https://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/81322, accessed on 14 October 2021.

[32] Watts, Rothschild, Annenberg School for Communications 15-16 December 2017, Understanding and Addressing the Disinformation Ecosystem, page 23, https://firstdraftnews.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/The-Disinformation-Ecosystem-20180207-v4.pdf, accessed on 11 October 2021.

[33] Ibid., 3.

[34] Paul Stockton, John Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, Defeating Coercive Information Operations in Future Crisis, 2021, https://www.jhuapl.edu/Content/documents/DefeatingCoerciveIOs.pdf, accessed on 11 October 2021.

[35] Christopher Paul, Miriam Matthews, RAND, The Russian “Firehose of Falsehood” Propaganda Model, 2016, https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE198.html, accessed on 12 October 2021.

[36] Idem.

[37] Ibid., 3.

[38] Brian Raymond, Foreign Policy, Forget Counterterrorism, the United States Needs a Counter-Disinformation Strategy, 15 October 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/10/15/forget-counterterrorism-the-united-states-needs-a-counter-disinformation-strategy/, last accessed on 12 October 2021.

[39] Ryan Serabien, Lee Foster, Fireeye Threat Research Blog, Pro-PRC Influence Campaign Expands to Dozen of Social Media Platforms, Websites, and Forums in at Least Seven Languages, Attempted to Pysically Mobilize Protesters in the U.S., 8 September 2021, https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2021/09/pro-prc-influence-campaign-social-media-websites-forums.html, accessed on 11 October 2021.

[40] Emerson T. Brooking, Atlantic Council, Before the Taliban took Afghanistan, it took the internet, 26 August 2021,https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/before-the-taliban-took-afghanistan-it-took-the-internet/, accessed on 15 October 2021.

[41] Hazrat M. Bahar, Taylor & Francis Online, Social media and disinformation in war propaganda: how Afghan government and the Taliban use Twitter, 9 September 2020, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01296612.2020.1822634?journalCode=rmea20, accessed on 13 October 2021.

[42] Emerson T. Brooking, Atlantic Council, Before the Taliban took Afghanistan, it took the internet, 26 August 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/before-the-taliban-took-afghanistan-it-took-the-internet/, accessed on 15 October 2021.

[43] Michael Hayden, US Army War College, Retired Gen. Michael Hayden, former Director of the NSA, and Director of the CIA, 30 June 2016, YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jab1rHt8xjI&t=34s&ab_channel=USArmyWarCollege; see: 36 min, accessed on 17 October 2021.

[44] U.S. Senate Hearing, Disinformation: A Primer in Russian Active Measures and Influence Campaigns Panel I; 30 March 2017, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-115shrg25362/html/CHRG-115shrg25362.htm; Testimony Senator King, accessed on 14 October 2021.

[45] Alna Polykova, Brookings Institute, Weapons of the weak: Russia and AI-driven asymmetric warfare, 15 November 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/research/weapons-of-the-weak-russia-and-ai-driven-asymmetric-warfare/, accessed on 13 October 2021.

[46] Walter Pincus, The Washington Post, New and old information operations in Afghanistan: What works?, 28 March 2011, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/new-and-old-information-operations-in-afghanistan-what-works/2011/03/25/AFxNAeqB_story.html, accessed on 14 October 2021.

[47] Jeff Jarvis The Guardian, Revealed: US spy operations that manipulates social media, 17 March 2011, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2011/mar/17/us-spy-operation-social-networks, accessed on 23 August 2021.