Abstract: Armed combat as a frontal clash of opponent forces compromises development of thousands of years. The engagement of land troops executes the realisation of military strategic concepts. The essay will describe the most important elements chronologically and view them closely through famous battles. From the early phalanx to cannons in the late Middle Ages to tanks during the First World War… several manifestations are to be discussed.

Problem statement: How were land manoeuvres formed from the ancient world to the 20th century?

So what?: The consideration of history helps with every military-strategic analysis. The long process of modernisation and the increase of scientific concepts should contribute to the understanding of successful operations and integrate their essence for the future.

Source: shutterstock.com/Morphart Creation

An Advance at Scale

“Manoeuvre is an advance at scale to a position of advantage in the enemy’s rear or flank. It allows an attacking force to gain a position from which it can inflict insupportable damage on its enemy.”[1] Considering the definition of manoeuvre warfare, it is common to separate it from attrition. Surprising and threatening the enemy through encirclement or different ways of flanking may provide a superior position on the battlefield. However, it is necessary to separate modern theories and concepts from historical facts and sources.

Manoeuvre is an advance at scale to a position of advantage in the enemy’s rear or flank.

In the history of military developments, one must especially show the means available–those in armament and mobility. There has been great diversity over the many thousands of years, such as different approaches to armour, tools for close or distant combat, and the use of war animals.

Paying attention to historical developments is advisable to gain a military advantage. Flank attacks yearned to anticipate during combats and have been used constantly. However, manoeuvre warfare is a modern phenomenon with a narrow definition opposing attrition tactics. Military success through surprise attacks is often a feature of this definition.

There are several historical examples when those manoeuvre strategies were used to achieve other goals (perhaps more latent and delayed ones), such as attacks against supplies and logistical goods or routes. What can be observed in innovative manoeuvres–be it with Alexander the Great, Caesar or Napoleon–is the quick solution to enemy offensives when they seemed inferior or lacked initiative. The risk of letting the enemy soldiers penetrate their ranks for encirclement is considered a successful method of clever tactics. However, defining these manifestations as entirely manoeuvre warfare is not always accurate. On the one hand, in earlier times, there was not always such a dichotomy between attrition and manoeuvre, and in historical war examples, various elements can be found simultaneously. In addition, many “manoeuvres” emerged in the event’s emotion, spontaneously out of necessity without any prior fixed strategy.[2] In contrast, the classic manoeuvres as training and military exercises naturally had a historically grown tradition.

Ancient Times…

In ancient societies, military conflicts were constant,[3] which can be seen as a socio-psychological burden. A large part of the population had war experience and, therefore, probably had a certain degree of traumatic dispositions. In Greek art, war was dealt with collectively. For the aristocracy, military careers provided identity.

The origin of war lies in the animal kingdom. War is characterised as organised violence. Combat operations have already been documented in the Paleolithic. The oldest weapons were wooden lances. As an example, the massacre in Talheim (Germany) around 5000 B.C. should be mentioned here. Since the Copper Age (4th millennium B.C.), the earliest weapons were daggers.

War is characterised as organised violence.

War technology has always been considered essential for general progress. Various studies confirm the overall cultural benefit of weapon technology. The possibilities of defence and the necessity of innovation are indicators of civilisational progress.[4] In the early Bronze Age, there were so-called “hilt plate swords” (up to 60 cm), and possibly the first spearheads in the early period (in Greece, for example, these were made of obsidian). These had slots in the leaf for attachment (found in Sicily, Spain and Saxony). By the middle of the 3rd millennium, the royal tombs on Ithaca already contained many weapons. Therefore, the Greek aristocracy had a special connection to the army and hunting.[5]

Palatial Period and the Iliad

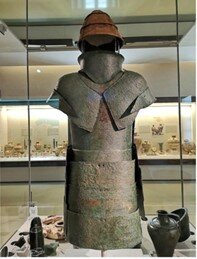

When Schliemann found the mask of “Agamemnon” in shaft grave A at Mycenae (approx. 1700 – 1500 B.C.), new types of swords and lances were found in the uncovered areas.[6] There were extremely long lances, which, due to their difficult handling, established a new technique–the lance thrust. The sword types A and B, which were also long (up to 1 m and with a centre of gravity far to the front), were very narrow and decorated with elaborate ornaments. The handles were often made of marble (Mycenae had great wealth and status from the beginning). Overall, from here on, sword fighting and its mastery were seen as a unique prestige and still reserved for the elite. In addition, the famous boar’s tooth helmet was added during this period; the shield was body-sized and often strapped on. Chariots with lances about 3 m long were also used. The armour of Dendra (approx. 1400 B.C.) was designed for chariots and made of bronze. The armour was powerful and resisted sword strikes.

New swords appeared in the following Palatial period (types C, D, F, G). In the Post-palatial period, the Naue II sword was the most widespread (oval cross-section, eastern Central Europe) and was similar to the Greek F and G swords.[7] The continental European Naue II sword was, therefore, not an innovation. Nevertheless, Naue II prevailed in the post-palatial period and remained for centuries. In the palace period 1400 – 1200 on Mycenae, the ruler’s legitimacy was based not primarily on war but religion. The Mycenaean army relied on mercenaries. The boar tooth helmet was also used, as were modern greaves. An infantry formation battle scene can be seen in vase paintings in Mycenae (Late Helladic IIIC). Then came the hedgehog helmet, the round shield and the use of two lances. The first iron tips/iron weapons appear in the early Iron Age (900 – 700 B.C.).

In the Iliad, Homer describes the following combat elements:

- Infantry (distance between the opponents) with the “promachoí” in front;

- Chariots – no squadrons, one lead alone;

- Loose setup – breaks were allowed;

- Phalanx attachment; and

- No melee! Only a few leave the formation.

Ranged weapons were crucial. These points fit very well into the late Geometric period.[8]

In the Greek Bronze Age, very long swords (decorated with various materials) were initially used, until after the Palatial period, the Naue II sword became widely accepted in Europe. As early as the 7th/6th century B.C., a prototype of the phalanx was developed. The military descriptions in myths and on art objects (vase of Chigi) serve to reconstruct ancient armies.

Dendra panoply, Mycenaean era, 1400 B.C.; https://grecorama.com/en/mycenaean-dendra-cemetery.

Mycenaean sword with golden and bronze handle; https://www.worldhistory.org/image/13805/bronze–gold-mycenaean-sword/.

Phalanx, Alexander and War Elephants

Since 800 B.C., the Greek city-states were constantly at war. Wars were omnipresent in the Greek polis and determined the chronological division of this era—the various wars are primarily used as historiographical key points.

During the 7th century B.C., a prototype of the phalanx was developed with a tight formation. A turning point was the introduction of the Corinthian helmet and the hoplite shield. Added to this was the hoplite phalanx (heavily armed rows) with the promachoí in the front row. These were mostly aristocrats. Horses were never a symbol of prestige in this era (contrary to the Middle Ages). There are depictions of mounted riders but no cavalry yet. Horses were still used here for chariots (until the 7th century). It is, therefore, appropriate to mention the Iliad as a war myth because Aristotle later informed Alexander the Great about this (including the norms and values). At the battle of Marathon in 490 B.C., the Greek commander Miltiades relied on his flanks, as they were also the weakness of the Persians. The cavalry supported the Persian flanks, but a breakthrough did not succeed. The Greek army (thinned out line, but steadfast) created an encirclement where the Persians were rounded up in the middle.[9]

A turning point was the introduction of the Corinthian helmet and the hoplite shield.

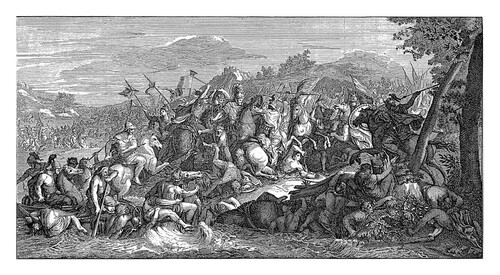

The Battle of Gaugamela is now considered one of ancient Greece’s most important land battlefields. On October 01, 331 B.C., 35,000 Macedonian foot soldiers faced 240,000 Persian soldiers and 40,000 cavalry.[10] War elephants had already been used, and the Persians used several scythed chariots. The Macedonian phalanx soldiers used much longer spears than the former hoplite phalanx. Darius III was provoked to start an attack. He ordered his chariot formations to ride through the Macedonian units, but this was a terrible mistake, as they got encircled. Alexander’s cavalry managed (due to excellent preparation) to start a massive counter-attack, and the Macedonians succeeded. The Persian king tried to flee but was assassinated by the satrap governor of Bactria.

The following battle example is the innovative manoeuvre of Alexander’s army against war elephants at Hydaspes. Alexander had a decisive disadvantage when he marched against King Porus in India. Horses shy away from elephants. So, he had to regroup the phalanx to attack the elephants directly (with arrows) so the cavalry could attack from the left. Alexander’s strategy succeeded as his cavalry completely compressed the Indian line. Since elephants act monstrously but highly unstable, the constriction caused the Indian infantry and cavalry to lose control.[11]

Alexander the Great demonstrated special skills in individual strategy on the ground during his manoeuvres. He did not shy away from directly attacking the opposing ruler on the battlefield. Inferiority could be compensated for with skilful flank attacks. The selection of war animals often had a decisive influence on the design of the manoeuvre. Heavily armed infantry formations (phalanx) became apparent. Especially Alexander used precise flanking manoeuvres and pushed for the enemy’s immediate annihilation. At Gaugamela, Alexander let the enemy get through a gap so that he could achieve a clever encirclement manoeuvre. In Gaugamela, “it was characteristic of Alexander´s cavalry to attack at an angle and not frontally, in order to cause confusion and prevent them from being bypassed by the enemy on the right side.”[12]

In Gaugamela, “it was characteristic of Alexander´s cavalry to attack at an angle and not frontally, in order to cause confusion and prevent them from being bypassed by the enemy on the right side.”

Alexander´s approach against the sickle chariots were based on javelin throwers. Alexander implemented a bold change in manoeuvre strategy here: the first phalanx line let the few unharmed charioteers through, who could then be knocked down by the second row. Therefore, Alexander´s phalanx arrangement demonstrated a successful situation adaptability.

Rome – Professionalisation and Structure

In Rome, it is appropriate to first look at Caesar’s battle of the civil war (49-45 B.C.) against Pompey–the Battle of Pharsalus, which was held in 48 B.C. As commander of around 54,000 legionnaires and 7,000 cavalry, Pompey opposed Caesar’s 22,000 legionnaires.[13] Pompey had obtained an increase in cavalry from the Senate, not including auxiliary troops. Psychologically, Caesar had an advantage because his legionnaires were fresh from the successful wars in Gaul and loyal to him. Pompey’s soldiers were mostly mercenaries. Caesar formed three lines of battle (under Sulla and Marcus Antonius). Pompey was well positioned (including on the left flank with three legions), but Caesar quickly detached his third line and made a fourth out of it in a hook formation so that the fourth line could hardly be seen. Caesar’s cavalry was quickly defeated, but the foot soldiers in the rear ranks held firm. Pompey tried a flanking manoeuvre.[14] As Pompey’s cavalry advanced, Caesar deployed spear throwers to the side. Pompey also fled with the horsemen, and Caesar took over the main line of battle. This manoeuvre approach was mainly successful due to an unexpected tactic during the battle.

Rome, from the 3rd century B.C., the “gladius” became the standard among swords and was used until the 3rd century A.D. The blade was about 55 cm long, and the handle could be made of wood, horn, or ivory. The short blade made it very stable and ideal for close combat. Also worth mentioning are the Roman catapults, which could throw bolts or stone balls hundreds of meters.

Augustus boasted in the depictions as the “pater patriae” who ended the phase of civil wars. Emperor Claudius succeeded in occupying Britain in 43 A.D., and Emperor Diocletian dedicated himself to defending the empire’s borders using fortifications. The professionalisation of the army is considered the flagship of Roman antiquity. From the 3rd century onwards, mobile field armies (mobile army, comitus) were used for the inland provinces. Structure and logistics were among the Roman army’s greatest strengths. The brilliant road construction, particularly, was the greatest aid to the land manoeuvres.

Structure and logistics were among the Roman army’s greatest strengths.

At the time of the Republic, there was an annual enlistment of men of military age (mostly farmers); recruitment was usually carried out by force. The principle of “Divide et imperais” also applied to military leadership. In the East, for example, there were five commanders-in-chief (magister utriusque militae) to avoid giving too much power to one individual. Several armies were also stationed in the West. The so-called “foederati” were purely Germanic troops, but they were an exception. M. Livius adapted some of the Macedonians’ military considerations, such as the appointment of several commanders instead of one. This meant that supply, storage location, schedule and setup were the responsibility of several people. In addition, in Rome, there was a “primacy of politics”,[15] according to which the military leaders were bound to the decisions of the Senate.

One legion had three ranks: 1. hastati, 2. principes, 3. tiarii (= reserve, experienced soldiers). Hastati and Principes had swords, two javelins and a long shield. A legion consisted of around 5,000 foot soldiers and 300 cavalry. At the end of the 2nd century A.D., there was an innovation: 6 centurias formed 1 cohort of 480 men (as a unit under the command of a centurion).[16]

In Rome, the chariot, especially the “briga”, had a high status, as it was used not only in war but also in ceremonies and for sporting purposes. The brigae had harnessed two horses, and the driver was standing. Then there were the triga, quadriga and even the seiuga (chariots with three, four or six horses). The Roman Empire had achieved a high degree of professionalisation in military policy. Nevertheless, the primacy of politics prevailed in the republic. Manoeuvres aimed at expansion had to be supported above all by clever logistics. The army’s leadership was concerned with the distribution of power to prevent too much concentration, and it was necessary due to the expansion of the Roman Empire (“divide et impera”). Caesar succeeded in wars using several flank attacks and as a competent commander. The Roman “gladius” became the standard sword until the 3rd century, but also catapults were used.

The Middle Ages

There has been little interest in military strategy in the research streams of medieval studies in recent decades. Mainly, there were cultural-historical references to legends. An exception here is research into war narratives in the Nibelungen, Willehalm or Roland´s Song. In the “chanson de Roland” or “Priest Konrad´s Song of Roland” (about 11th century), the focus is on “militia Dei”, i.e. military service for God. The theme of the crusades against the Muslims (“heathens”) is also about the religious fight against evil and immorality.[17] However, in contrast to the individualistic heroic epic, the poetry of the Crusades, for example, is also of a military-political nature. Wolfram v. Eschenbach’s Willehalm, along with his battle descriptions, is important in this regard. The Willehalm epic stands in clear contrast to the Roland song. Here, everyday war life is not portrayed in a heroic and glossed-over manner. There is no war propaganda or religious calls for crusades against Muslims. The “bellum iustum”, invoked in Roland’s Song, plays little role. Rather, v. Eschenbach describes the cruelties of battles and the suffering that comes from them. Since the patterns in the narrative regarding descriptions of war appear so different and multifaceted, literary studies have recently paid more attention to this complex of topics.

The theme of the crusades against the Muslims is also about the religious fight against evil and immorality.

Historical discourse analysis also finds a lot of information in these (courtly) poetry sources. However, more precise Middle High German texts were used to interpret weapons and tactics. The literary texts of the Middle Ages function as reflections with which a reconstruction should succeed. Historical science strives to integrate literary sources, but it is still important to keep them strictly separate. The approaches of the linguistic turn in historiography implemented the idea that language represents reality. Discourse analysis also leads to the examination of the narrative in texts. In the heroic epics, the suitability of a warrior and the “killing competence of the hero” are particularly relevant, especially concerning the character.[18] In courtly poetry, heroic epics and especially in “Parzival”, the Christian element is strongly pronounced in a moral context. The stories about chivalry focus on the character’s development and how they prove themselves in life. Battle descriptions seem to represent a minority compared to other motives.[19]

One also relies on artistic representations of battles. However, combats were not always realistically portrayed.[20] Generally, the beginning and end of a battle are the most important moments in pictorial representations, while dying in the battle played little role. There was also very close combat and hardly any clear separation of the fronts.

The following weapons are shown in the battle depiction of Bicocca 1525: long pikes, halberds, cannons, and stones. It is, of course, known that the horse was a prestige object. Because the knight in full armour was immobile without a horse. Weapons were specifically developed that could knock the rider off the horse. The jousting as an elite event was long considered a military exercise but was largely phased out in the early modern period. In addition to the various swords, the soldiers had the Warhammer, aimed at smashing the enemy’s helmet and armour thanks to its special shape.

In the 16th century, new and better weapons also required innovation – “radically altered infantry and cavalry tactics indirectly changed the pace of war”.[21] Firearms were already relevant in the battles of Bicocca and Pavia in 1525. Gunpowder was also used for defence (not just for fortifications). Because of new tactics, discipline became mandatory. However, England was weak at innovation, partly because of the traditional “romantic transfiguration of the bow and arrow.”[22] As a result, it was said that modernisation was difficult to accept. At that time, the “pike squares” had become established in Switzerland. However, the pikes were complicated to use and required long training.

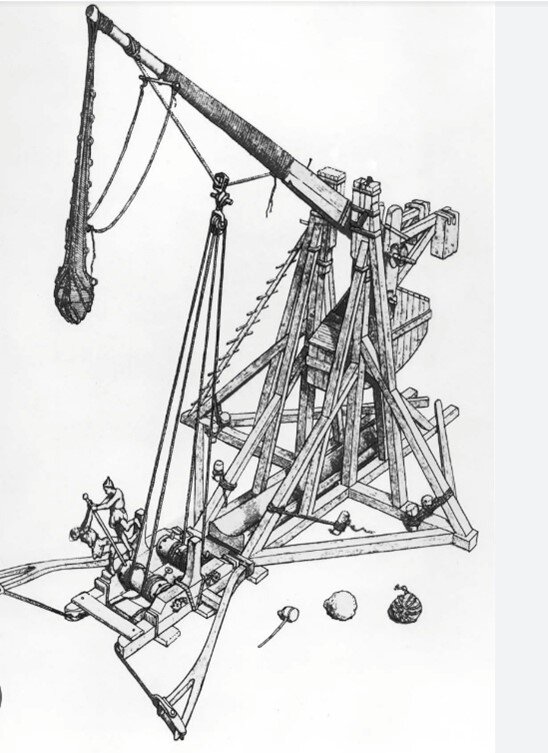

Looking at one of the well-known land battles of the Middle Ages, the siege of Orléans in 1428/29, the following parameters emerge: the English occupying troops tried to maintain the occupation of their forts. The French gained increasingly with massive storms and ever-increasing reinforcements, although the English set up entrenchments (bastilles) along the Loire. Nevertheless, the Bastille St. Lour was stormed, and the English occupiers were forced to retreat from Orléans. These conflicts were characterised by the use of various weapons–arrows, swords, catapults, lances, morning stars, and pikes.

Medieval operations could have formed three ranks with archers and crossbowmen in the front. The infantry seemed the most important unit, whereas heavy cavalry became increasingly unattractive in the late Middle Ages. In addition to skirmishes, the war tactics of the Middle Ages were largely sieges with cannons (very static due to the mass). The ‘rules’ for medieval wars were determined by the church using catalogues of fines.

The infantry seemed the most important unit, whereas heavy cavalry became increasingly unattractive in the late Middle Ages.

The Battle of Towton in 1461 between the Yorks and Lancasters is considered one of the bloodiest battles, although the manoeuvre only lasted a few hours. Again, it became clear that the number of soldiers did not have to mean victory. The inferior York soldiers supposedly had the advantage because of the wind in that their arrows flew well, but those of the Lancaster soldiers got stuck in front of their opponents. A bitter melee followed this. The Lancaster army fled, its soldiers being killed or drowned in the river.[23]

Since the siege of fortresses and castles was an essential aspect of medieval land warfare, powerful catapults were used. A device that came from China was particularly feared in Europe since the 6th century: the trebuchet. Its area of operation extended across Asia, the Mediterranean region, and Europe. In contrast to standard catapults, the trebuchet could throw projectiles weighing 1000 kg. In the Islamic world, this weapon was found to be very much mentioned in the scriptures and was widely used in their armies.[24] The number of weapons in the Middle Ages was large and diversified. Among the cannons, for example, the French field cannon (culverin) should be mentioned, which was used until the early modern period. Attached on a two-wheeled mount, it could fire relatively small balls between 0.5 and 5 kg. The culverin served as a precursor to the later field guns. The all-purpose weapon knight’s sword had an average length of 1 m and weighed up to 1.3 kg. Armoured cavalry used this type until the 14th century, primarily as a slashing weapon.

In the Middle Ages, the attacks and manoeuvres often took the form of siege battles. Accordingly, weapons and protective devices were developed and improved. Chivalry and mounted knights as a romanticised ideal were greatly reflected in poetry, but the most important unit was the infantry. Military operations often had to take place through hand-to-hand combat. The military service of certain families also established their later political and social positions of power. Since wars have always been expensive for princes to enforce their claims, major decisive battles with high losses were avoided. The “Landsknechts” were the most common phenomenon in the late medieval army. They did their military service for the highest pay.[25] Most of the weapons they used were lances, swords, bows, and pikes, but also heavy artillery at the end of the Middle Ages. The medieval infantries could also be formed as phalanxes. Cavalry units were not obligatory during engaging attacks (e.g. in the Swiss army). The introduction of gunpowder, i.e. firearms, was revolutionary and made the horsemen with simple lances inferior.

The “bastard culverin” cannon, France; https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/812566.

The “trebuchet” catapult; https://www.britannica.com/technology/trebuchet.

Early Modern Period

While close combat was crucial in the Middle Ages, there has been a greater turn to long-range weapons in modern times. The Thirty Years’ War can be considered exceptional in warfare: it was predominantly shaped by guerrilla tactics.[26] Mercenary troops were deployed in relatively small units, and commanders avoided major field battles. General Wallenstein even permitted looting. In general, the barbaric raids of looting to terrorise the population were accompanied by the terrible results of various epidemics and periods of famine. The 19th century, in particular, was characterised by innovations and a focus on land manoeuvres. Speed was the top priority here regarding the fighter’s body and the transmission of messages.

The Thirty Years’ War can be considered exceptional in warfare: it was predominantly shaped by guerrilla tactics.

The late Enlightenment was, of course, also reflected in military-political considerations, although its dogmas were also abused (e.g., the reference of the French Revolutionary Wars to Rousseau, “War is only a matter between states”; the declaration of war in 1792 was also formulated with the defence of citizens and property). However, there was increasing doubt about the legitimacy of these French revolutionary and later expansion wars from 1792 to 1799.[27] A paradigm shift took place here when one can state that “the consensus of the late Enlightenment thinkers described by Geoffrey Best for the late 18th century was replaced after 1815 in the area of ius in bello by a consensus of the monarchs.”[28]

From Napoleon to The Hague

In the 18th century, the French army had renewed far-reaching strategies for more successful operations through modern approaches. Even before the Napoleonic Wars, others pointed to the importance of using more powerful artillery. France still relied heavily on foreign regiments. During the upheavals, the militia was finally disbanded in 1791. Under Marquis de Lafayette, the National Guard was formed. Together with the process of the “levée en masse”, the modern people´s army was created. With the Conscription Act, there were also troop reserves.

In the 18th century, French military theorists dealt with the problem of linear tactics.[29] Then, the focus on the offensive and the importance of artillery arose. As a formation of the “colonne d´attaque” (about 800 men), the armed forces were to advance. Operationally, they had to abandon rigid linear tactics by observing the American War of Independence and turn to petty wars. In the past age of manoeuvre strategy, it had become increasingly important “because its objects of attack were less (…) the line infantry itself, but the lifelines in need of protection in the hinterland between the magazine base and the camp disposition.”[30] Here, the French already used elements of manoeuvre tactics when they undertook deceptions, mock attacks and “permanent battles against the front posts”[31] during the Revolutionary Wars.

Napoleon then perfected these concepts and used his own manoeuvres, and he had a unique approach to spontaneous planning when transitioning to a tactical situation.[32] His Grande Armée achieved a mythical status and was considered invincible for a long time. At this point, the French army demonstrated a “masterful command of the operational art”.[33] Napoleon recognised the importance of propaganda early on with the regular military bulletins. This propaganda was obligatory when the population’s approval came through the permanent state of war. The arguments of the “bringer of civilisation”, like Alexander, also played a role. What was essential in Napoleon’s reforms was the centralisation of command. The French General Staff would not criticise in times of victory.

Napoleon recognised the importance of propaganda early on with the regular military bulletins.

The strength of the Grande Armée in land manoeuvres also resulted from the destruction of the French navy at Trafalgar in 1805. Napoleon consistently used the ‘manoeuvre sur les derrières’, where the main forces focused on the enemy’s rear ranks to achieve a massive breakthrough. “His was a philosophy of warfare which demanded that an army remains on the strategic offensive, a reality that in turn coloured Napoleon’s operational and tactical precepts. Each operation, each manoeuvre, and each battle was carefully designed to create the circumstance for a decisive engagement, a battle of annihilation.”[34]

Despite all his achievements, Napoleon also made ill-considered mistakes in dealing with his divisions, causing him to lose control more and more, especially evident after the defeat in Russia in 1812.[35] 1805, Napoleon let the Russian army advance in Austerlitz and surrounded the strategically ill-acting Russians. Then, he was able to carry out the counterattack after General Kutusov deliberately avoided the right flank of the French.[36]

The most famous European battle at the beginning of the 19th century was undoubtedly the Battle of Leipzig, in which over 500,000 soldiers were involved. The coalition warfare brought together three armies (Bohemian, Silesian and Northern Army) against Napoleon, who, despite the losses in Russia, was later able to recruit over 300,000 men into his army (In the Russian campaign of 1812, Napoleon had 610,000 men at his disposal). Napoleon’s strength was again the artillery (previously, he relied more on fast mobility), but his cavalry had weaknesses this time. Napoleon wanted to relaunch a separate attack, but his small cavalry could not prevent the encirclement. In the spirit of the “Balance of Power”, Coalition warfare was required to prevent Napoleon from dominating European politics once again.[37]

Apart from military decisions, political liberalism had dominant features in European politics in the 19th century and, thus, a regulation of bilateral relations. The suffering of the soldiers also had to be curbed. For this purpose, the Geneva Convention of 1864 stipulated the creation of private aid societies with neutral medical personnel under the umbrella of the Red Cross. The agreement in the form of the Petersburg Declaration of 1868 prohibited the signatory states from using projectiles with an explosive force of less than 400 g. In 1873, the Institut de Droit International was founded as a multilateral organisation to monitor compliance with the rules. This was followed in 1899 by the Hague Declaration on the Prohibition of the Use of Projectiles Containing Asphyxiating or Poisonous Gases and the Declaration on the Prohibition of Projectiles that Easily Expand or Flatten in the Human Body.

Finally, on October 18, 1907, the essential agreement concerning the laws and customs of land warfare appeared. It was determined which weapons were allowed.[38] The convention aimed to help wounded soldiers from armies in the field. Firearms were influential in land manoeuvres in the 19th century. Since the Middle Ages, weapons technology has been based on using black powder. In the 19th century, the aim was to make it easier for soldiers to handle weapons and to increase shooting speed (magazine storage of many cartridges). However, an average infantry rifle only managed a few shots. Hence, the bayonet had to be attached for later close combat, and the blade length was variable—improvements followed in the holder.

The wars of the early modern period showed further innovations when there were deviations from classic manoeuvres of the land forces. The trend was now more in the direction of long-range weapons. Innovations in military strategy, more effective artillery from the middle of the 18th century onwards and the emergence of major coalition wars shaped the modern era. In particular, establishing international standards was considered a turning point in the 19th century. The reconceptualisation of warfare, coming from France and Napoleon in particular, is essential to implementing manoeuvre tactics. In particular, advancing heavy artillery as a relevant unit in its own right is an achievement.

Innovations in military strategy, more effective artillery from the middle of the 18th century onwards and the emergence of major coalition wars shaped the modern era.

Two World Wars

The First World War is classified as an “epochal shock”.[39] Since this military turning point, the war has become noticeable to the general population, and its characterisation as an industrialised war also illustrates the violence.

During the manoeuvre of the Austro-Hungarian Army in 1911, those responsible deliberately chose strenuous conditions. The manoeuvre area was moved to rugged mountain terrain due to command, safety and communication strains. Franz Ferdinand and Baron von Hötzendorf led the manoeuvres. Some military attachés also took part. Red and blue armies were divided. Archduke Franz Ferdinand assessed in a letter on 15 September 1911: “(…) Although both parties were already faced with difficult tasks by the grouping in the initial situation, which were exacerbated by the pathless, confusing and mountainous terrain, the cooperation of the individual columns (…) was very good and showed significant progress compared to previous years. Above all praise, however, was the marching ability and the good spirit of the troops, who overcame the exertions in the resource-poor terrain with great freshness (…).[40] During this manoeuvre, the first and second Army Theatre Commands were responsible for securing the country´s means of transport, food (a major problem was cattle slaughter due to rampant diseases) and sanitary care. Ambulance transport also had to be regulated via routes and light railways.

Since 1866 and 1871, Germany initially had an outstanding position in land manoeuvres. Not only were the Prussian weapons and tactics exceptional (e.g. Dreyse needle rifle with seven shots/minute and high accuracy added to this were the advantages of weak leadership in Austria-Hungary and France, which made the “German war-making” so pretentious.[41]

However, the political decisions leading to war in 1914 demonstrated the inability of anticipation in Germany and Austria-Hungary. The German politicians could not imagine that the Russian Empire could intervene in Serbia this time, as it didn’t during the Balkan War. Austro-Hungarian ministers and diplomats debated in June 1914 how to proceed with the Serbian case. Emperor Franz Joseph turns to Wilhelm II. Diplomatic alliances and mutual declarations of war provoked a world war that had been supposed to stay just local.

The political decisions leading to war in 1914 demonstrated the inability of anticipation in Germany and Austria-Hungary.

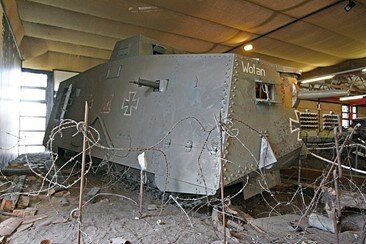

Starting from a quick war like 1870, the weakness of the German military soon became apparent in 1914–long wars. The military leadership of the German Empire was also largely unsuccessful. The First World War brought significant innovations in land manoeuvres, especially in technology. The first tanks were developed in France and Great Britain in 1915 and were used from September 1916. The French prototype of the Renault FT from 1916 was initially designed as a lighter combat vehicle. This was contrasted with the 70-tonne FCM 2C. The German A7V was not used until March 1918 at St. Questing. Before that, the French and British tanks had not yet had a decisive effect on the war. The British army also sent out their I/II from 1916. Furthermore, the German A7V was cumbersome but fast compared to others. Its main weakness was the cooling of the engines.[42]

Horses were also still in active use at this time. Looking at the manoeuvres of T. E. Lawrence, the Bedouin camels played a special role in the skirmishes in the guerrilla war. Moreover, communication also required rapid improvement. Concerning the “Blitzkrieg”, this seems particularly evident with a “flexible, telephone-controlled movement”.[43] In the First World War, telephone communication replaced the physical presence of the commander: “From a media theoretical perspective, the form of communication comes into focus with regard to its apperceptive effects. The first internal military debate that falls within this analytical framework is that of perception and the commander’s ability to lead under the conditions of presence or absence.”[44] Radio technology also allowed psychological guidance after 1918. From 1914 onwards, the tactics were often on the defensive, although they were on the mobile offensive–to save forces. Protective devices against artillery were set out in separate regulations (field fortification regulations as early as 1908, e.g. wooden shrapnel roofs). About 6m of earth was necessary against howitzers. A continuous line with a “permanent position” was favoured; the gaps between were protected with supporting flank fire.

As late as 1918, Germany, in particular, was shaping the field of military science with its own universities as a response to a “tendency towards bellification across society”.[45] Scientific knowledge should be conveyed to political and military leadership. The effects of the First World War on soldiers were also particularly evident in a new psychopathological illness: war tremors/shell shock. This form of shaking neurosis was so widespread that not only psychiatrists and psychoanalysts but also writers such as Karl Kraus dealt with it. Establishing its military psychology highlights the urgency of ensuring the psychological hygiene of soldiers. This was particularly true for the ground forces. General hygiene and disease prevention can also be described as a key element of land warfare.[46]

As late as 1918, Germany, in particular, was shaping the field of military science with its own universities as a response to a “tendency towards bellification across society”.

For Great Britain, imperial dominance was a major concern parallel to the confrontation with Germany. British military historians state, for example: “Germany for its part abandoned the focus that was its Prussian heritage, and fought two world wars with what amounted to no strategy at all.”[47]

Soviet military theorists and commanders realised that singular “battles of annihilation” on a limited battlefield no longer seemed appropriate. According to theorists of the 1930s, the Red Army had to use shock armies in deep operations (equivalent to the German stormtroopers), which were supposed to break through into enemy lines during an attack. However, this required support from air forces in preparation.[48] Soviet manoeuvres didn’t seek for one decisive battle. The Red Army operated in waves due to its superior manpower. The doctrine of “deep battle” (e.g., by Georgij Isseron in the 1930s) showed a combination of several manoeuvre tactics and how to build up deep defence lines. These strategic thoughts and realisation in the Second World War were based upon many experiences since the defeat against Japan in 1905. A massive breakthrough was intended, but the annihilation of really important targets like infrastructure was the long-term goal.

In the offensive, the Red Army had certain procedures: no pause, not to allow the enemy to retreat or realign strategically.[49] The “shock armies” method can be seen as an element of attrition, i.e., the successive complete destruction of the enemy–with the aim of rapid advance (several dozen kilometres per day).[50] In particular, the advance from March/April 1945 to Lower Austria (as well as the advance of Soviet soldiers coming from Hungary in general) forced the Wehrmacht to retreat in an often uncoordinated manner.[51] Although the balance of forces in the final phase of the war was in favour of the Red Army, not all objectives could be achieved. The reason was that there was too little ammunition for the Soviet artillery in the early stages.[52]

Although the balance of forces in the final phase of the war was in favour of the Red Army, not all objectives could be achieved.

Innovations in technology and mobility among the Axis powers and Allies were characteristic of the Second World War. The tank battle near Kursk in the summer of 1943 was considered one of the key moments of the Second World War. This manoeuvre in Operation “Citadel” demonstrated an offensive against the Soviet line of 150 km. The German troops brought together around 800,000 soldiers, over 1,000 aircraft, and over 2,000 tanks against more than 4,000 Soviet tanks and 1.3 million soldiers.[53] The German offensive could not use the element of surprise, and the breakthrough was not achieved (only a few kilometres at certain points). There were significant losses on both sides, including material ones. However, the Soviet Union was able to compensate for this better. The Soviet tanks would have been much more agile in close combat than the German models.[54]

The Second World War was a period of the greatest advances in military history–weapons, mobility, medical services, and intelligence; all areas were improved. In France, for example, the focus was on funding for ground troops and less on the air force. Therefore, the Germans were able to get through French airspace quickly. The aviators (including bomber squadrons) had a significant influence on the success of the German Blitzkrieg. Bombing cities was a popular method.

Advanced motorisation determined the design of manoeuvres. “Combined forces of tanks, motorised infantry and artillery penetrated an opponent’s defences on a narrow front, (…). Radio communications were the key to effective Blitzkrieg operations, enabling commanders to coordinate the advance and keep the enemy off balance.“[55]

The Blitzkrieg manoeuvre was no strategy in itself; it seemed to be a term to define this German operating approach somehow, but it was also used for propaganda intentions. By the summer of 1942, the German force achieved operational triumphs. But from Kursk at the latest, the Wehrmacht and SS divisions were forced to build deep defensive lines (often, these were entire villages). In land manoeuvres, the German weapons were at least equal to, and sometimes better than, those of the Allies. The tactic now also included a lot of mines. The perfected tanks were the innovation of the war strategy. On the German side, it was the Panther/ Tiger/ Sturmtiger/ Jagdpanther, and on the Soviet side, it was the T-34/85, which became the most famous and internationally recognised model (from 1944). Panthers and Tigers, in particular, pushed the Soviet Union to improve. Although victorious at Kursk, the Soviet Union was nervous about the Panther’s three times greater range.[56]

Some military scholars are critical of the adaptation of modern manoeuvre warfare concepts to historical wars, as well as theoretical writings or mislead interpretation. These objections refer to an inadequate methodology of a (new) potential manoeuvre representation of the past. “The [U.S.] Army’s use of manoeuvre warfare can be marked by the 1982 version of the FM 105-1 Operations, which introduced the operational doctrine of “Air, Land, Battle”. It has a complex background of thought involving the Wehrmacht legacy and the mirror image of the Soviet deep-operations doctrine. The learning about the Wehrmacht and Soviet Army during this period was not historical but ideological.“[57]

The [U.S.] Army’s use of manoeuvre warfare can be marked by the 1982 version of the FM 105-1 Operations, which introduced the operational doctrine of “Air, Land, Battle”.

The alleged Blitzkrieg strategy was not a Wehrmacht doctrine but rather a paraphrase for a new type of overwhelming offensive. Here, the fact has caught up with the theory. This example shows that the phenomenon cannot always be attributed to a precise strategy but that special features can also be recognised in every military conflict.

The two World Wars had lasting effects due to their industrialised and all-encompassing dimension. Motorisation and advances in mobility, new forms of command communication, and scientific efforts in the military led to profound innovations. Nevertheless, it has been shown repeatedly that many manoeuvres often require spontaneous restructuring due to external conditions (e.g. the factor of low tide on D-Day).[58]

German tank A7V; https://www.welt.de/geschichte/article161744907/Enge-Gestank-und-ohrenbetaeubender-Laerm.html.

Conclusion

Manoeuvres are designed to enable one’s own armed forces to succeed through targeted attacks–through initiative, surprise or penetration through enemy flanks. Encirclement can be seen as another strategy. One of the most common manoeuvres in antiquity was the flank attack. From the hoplite warriors in Greece to the soldiers in the Roman Empire, this tactic was often used to turn around difficult situations in current battles.

In the Middle Ages, rulers or generals increasingly relied on mercenaries (Landsknechts), but avoided large battles for fear of loss. As compensation, the armies sometimes used raids to weaken the opponent—the siege wars aimed at destroying the political centre, often involving the civilian population. Ultimately, the common infantry was the mainstay of the medieval army. Modern times brought about a change to distance weapons and thus to new manoeuvre considerations. While innovations in the early modern period were still muted, 18th-century Europe saw a remarkable turn to heavy artillery.

The conduct of war in the Thirty Years’ War was characterised by minor skirmishes. Napoleon (and other French military strategists) forced the use of strong artillery. The encirclement became increasingly visible during the World Wars in the 20th century. The first tanks were a technological milestone for dynamic mobility in war. However, due to their imperfections, they still played a subordinate role in the First World War and were not decisive.

The first tanks were a technological milestone for dynamic mobility in war.

Military innovations spread very fast and contributed to the overall cultural development of a society. The effectiveness of an army was often not characterised by troop numbers but rather by situational flexibility. This specific point is well described in “The Art of War” by Sun Tzu. To describe the historical development of the manoeuvres, consideration must be given to whether there is an adequate definitional distinction from other land war tactics. In summary, the combination of manoeuvre strategies and attrition can often be seen in retrospective analysis. However, it is particularly evident in the pre-modern period that to what extent skilful adaptation developed into clever manoeuvres, a rigid separation of manoeuvres is often not given. The idea of generating such an advantage on the battlefield through targeted strategy in the operation phase was not always a previously considered concept by the commanders. However, looking at the 20th century can reveal an increased discovery of manoeuvre warfare. Nowadays, there is a lot of discussion about the current relevance of manoeuvre warfare, and some military theorists even talk about the death of this strategy. For historical science, the solution may lie in the individual analysis of the development of the art of war in specific studies.

Dr. Simone Weninger, BA, MA. As a contemporary historian, my field involves political, cultural, scientific, military and diplomatic history from the 19th century to the present day. Latest publications: “Niederösterreichische Politik 1934 – 1938, PhD diss., University of Vienna 2022. “Kriegsgräberfürsorge in Niederösterreich”, published in: Truppendienst (October 2023). https://www.truppendienst.com/themen/beitraege/artikel/kriegsgraeberfuersorge-in-niederoesterreich. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone.

[1] Anthony King, “Is Manoeuvre Alive?,” October 2022, https://wavellroom.com/2022/10/07/is-manoeuvre-alive/.

[2] William F. Owen, “Just Call It ‘Warfare’: Why Manoeuvre Warfare Retards Progress in the Profession of Arms,” The Warfighting Society, February 18, 2022, https://www.themaneuverist.org/post/just-call-it-warfare-why-manoeuvre-warfare-retards-progress-in-the-profession-of-arms-by-william.

[3] Mark Cartwright, “Warfare in Classical Greece,” April 2020, https://www.worldhistory.org/collection/73/warfare-in-classical-greece/.

[4] “Evolution: wie die Waffentechnik die Entwicklung der Menschheit vorantrieb,” https://www.psychologie-aktuell.com/journale/gesellschaftskritik/bisher-erschienen/inhalt-lesen/evolution-wie-die-waffentechnik-die-entwicklung-der-menschheit-vorantrieb.html, accessed on November 2024.

[5] The Megaron was centralised and controlled by elite warriors. The crisis of the palace centres arose from a weakness against foreign mercenaries – the fortresses were easy to take.

[6] Heinrich Schliemann, Trojanische Alterthümer. Bericht über die Ausgrabungen in Troja, (Leipzig, 1874), 16, in Deutsches Textarchiv, https://www.deutschestextarchiv.de/schliemann_trojanische_1874/22, accessed December 18, 2024.

[7] Florian Ruppenstein, “Weapons and Warfare in Ancient Greece,” lecture at the Institut of Classical Archaeology Vienna, (winter semester, 2011).

[8] Josho Brouwers, “Swords in Ancient Greece,” Ancient World Magazine, November 25, 2015, https://www.ancientworldmagazine.com/articles/swords-in-ancient-greece/; see also: Oliver Dickinson, The Aegean Bronze Age, (Cambridge University Press,1994).

[9] Paolo Cau, Die 100 größten Schlachten. Sie haben die Welt verändert. Von Kadesch (1285 v. Chr.) bis heute, ( Kaiser-Verlag, 2007), 27.

[10] Florian Ruppenstein, “Weapons and Warfare in Ancient Greece,” lecture at the Institut of Classical Archaeology Vienna, (winter semester, 2011).

[11] Hans-Joachim Gehrke and Helmut Schneider, eds., Geschichte der Antike. Ein Studienbuch, 2nd ed., (J. B. Metzler-Verlag, 2006), 202.

[12] 80% of the Indian riders and about 80 elephants were killed. In conclusion, one can say that elephants, deployed in a well-structured formation, posed a high level of danger to the opponents. Also because horses instinctively flee from them. Therefore, war horses were occasionally trained alongside elephants (as seen at the battle of Pyrrhus against Sparta in 272 B.C.). Here the Spartans dug pits into which the elephants fell. Of course, the Carthaginian Hannibal and his elephants were also legendary. See: Rainer Pöppinghege, ed., Tiere im Krieg. Von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, (Ferdinand Schöningh, 2009).

[13] Paolo Cau, Die 100 größten Schlachten. Sie haben die Welt verändert. Von Kadesch (1285 v. Chr.) bis heute, ( Kaiser-Verlag, 2007), 35.

[14] Appian, De bello civili, book II, paragraph 49: “Caesar at that time had ten legions of infantry and 10,000 Gallic horses. Pompey had five legions from Italy, with which he had crossed the Adriatic, and the cavalry belonging to them,” https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Appian/Civil_Wars/2*.html;

see also: “Kräfteverhältnisse und Verluste in der Schlacht von Pharsalos während Cäsars Bürgerkrieg im Jahr 48 v. Chr.,” https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1272737/umfrage/kraefteverhaeltnisse-und-verluste-in-der-schlacht-von-pharsalos/, accessed on August 20, 2024.

[15] Myles Hudson, “The Battle of Pharsalus,” September 2019. https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Pharsalus.

[16] Hans-Joachim Gehrke and Helmut Schneider, eds., Geschichte der Antike. Ein Studienbuch, 2nd ed., (J. B. Metzler-Verlag, 2006), 304.

[17] “Die Darstellung des Feindes im Rolandslied. Monströse Darstellung der ‘Heiden’ als Legitimation zur Vernichtung?,” September 20, 2018, https://fantastic-beasts.blogs.uni-hamburg.de/die-darstellung-des-feindes-im-rolandslied/.

[18] Hermann Reichert, Ältere deutsche Literatur, Lecture summer semester 2018, (facultas Verlag, 2018), 116; see also: https://www.unifr.ch/orthodoxia/de/assets/public/Lehre/HS2020_Sakramente/Mensch_Sakrament.pdf.

[19] Christine Grieb, “Schlachtschilderungen in Historiographie und Literatur (1150 – 1230),“ in: Krieg in der Geschichte (KRIG), Vol. 78, (Ferdinand Schöningh, 2015), 61.

[20] In the depiction of the Battle of Tannenberg in 1410 by the Pole Jan Dlugosz, the formation of the Teutonic Order is portrayed as complete chaos, while the Polish army is portrayed in absolute order.

[21] David Eltis, The Military Revolution in Sixteenth Century Europe, (I. B. Tauris Publishers, 1995), 136.

[22] Idem.

[23] John Sadler, Towton: The Battle of Palm Sunday Field 1461, (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2011).

[24] Reinhard Baumann, “Landsknechte,” Historisches Lexikon Bayerns, https://www.historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de/Lexikon/Landsknechte, accessed on December 15, 2024.

[25] The Golden Horde under Genghis Khan is also said to have frequently used the trebuchet; see: Paul E. Chevedeen et al., ”Das Trébuchet – Die mächstigste Waffe des Mittelalters,“ Spektrum, September 01, 1995, https://www.spektrum.de/magazin/das-trebuchet-die-maechtigste-waffe-des-mittelalters/822529.

[26] Karl Vocelka, Geschichte der Neuzeit 1500 – 1918, (Böhlau-Verlag, 2010), 438.

[27] Daniel Marc Segesser, “Humanising war! You might as well talk of humanising hell,” Recht und die Humanisierung des Krieges in der industriellen Gesellschaft Europas, 391 – 406, in: Krieg in der industrialisierten Welt, Krieg und Gesellschaft, Vol. 4, eds. Thomas Kolnberger, Benoît Majerus and M. Christian Ortner, (Ferdinand Schöningh, 2018).

[28] Ibid., 393.

[29] Siegried Fiedler, Taktik und Strategie der Revolutionskriege 1792 – 1848, (Bernhard & Graefe, 1988), 169.

[30] Ibid., 93.

[31] Ibid., 169.

[32] Ibid., 171.

[33] Alan Forrest, „Die Französische Armee im Napoleonischen Zeitalter,“ 97 – 114, in: Die Völkerschlacht bei Leipzig. Verläufe, Folgen, Bedeutungen 1813 – 1913 – 2013, Beiträge zur Militärgeschichte, eds. Martin Hofbauer and Martin Rink Vol. 77, (Walter de Gruyter, 2017), 97.

[34] Berke Gursoy, „The Eagle’s Rise: Napoleon Bonaparte’s First Campaign and the Birth of Napoleonic Warfare,“ Armstrong History Journal, April 03, 2019, https://armstronghistoryjournal.wordpress.com/2019/04/03/the-eagles-rise-napoleon-bonapartes-first-campaign-and-the-birth-of-napoleonic-warfare/.

[35] Siegried Fiedler, Taktik und Strategie der Revolutionskriege 1792 – 1848, (Bernhard & Graefe, 1988), 171.

[36] Ibid., 178.

[37] In principle, a basic consensus of the powers was required from the 18th century on (treaty of Utrecht 1713), which in reality envisages the distribution or relocation of lands or compensation to rulers for the purpose of the „equality of power“. This concept was particularly established in French journalism and peace philosophy, Although it was a superficial term and difficult to define. In fact, the desire for a “juste équilibre des puissances” was more due to war fatigue than as a reaction to philosophical suggestions. See also: Eberhard Birk, Die “Völkerschlacht“ bei Leipzig vom 16. bis 19. Oktober 1813. Zum Verlauf der Operationen im Spannungsfeld der Koalitionskriegsführung, 115 – 140, in: Die Völkerschlacht bei Leipzig. Verläufe, Folgen, Bedeutungen 1813 – 1913 – 2013, Beiträge zur Militärgeschichte (Vol. 77), eds. Martin Hofbauer and Martin Hink, (Walter de Gruyter, 2017), 118 – 121.

[38] Poisoned weapons were forbidden and surrendering soldiers were not allowed to be injured or killed. Prisoners of war had to be treated with humanity (but could be used for work). It was also said that the population of an occupied territory should not be forced to swear allegiance to the enemy power.

[39] Frank Reichherzer, „Wehrwissenschaften. Zum Wechselverhältnis von Krieg und Wissenschaften im Zeitalter der Kriege,“ 177 – 196, in: Mit Feder und Schwert. Militär und Wissenschaft – Wissenschaftler im Krieg. Wirtschaft, Politik und Gesellschaft, eds. Matthias Berg, Jens Thiel and Peter Th. Walther, Vol. 7, (Frank Steiner Verlag, 2009), 181.

[40] „Die Armeemanöver in Nordungarn im Jahre 1911,“ edited by Operationsbureau des k.u.k. Generalstabes, (Streffleurs Milit. Zeitschrift, 1912), 277.

[41] Jeremy Black, Land Warfare since 1860. A Global History of Boots on the Ground, (New York, 2019), 34.

[42] Peer Körner, „Erster deutscher Panzer: Enge, Gestank und ohrenbetäubender Lärm,“ February 2017, https://welt.de/geschichte/article161744907/Enge-Gestank-und-ohrenbetaeubender-Laerm.html.

[43] Stefan Kaufman, Kommunikationstechnik und Kriegsführung 1815 – 1945. Stufen telemedialer Rüstung, (Wilhelm Fink, 1996), 376.

[44] Ibid., 377.

[45] Frank Reichherzer, „Wehrwissenschaften. Zum Wechselverhältnis von Krieg und Wissenschaften im Zeitalter der Kriege,“ 177 – 196, in: Mit Feder und Schwert. Militär und Wissenschaft – Wissenschaftler im Krieg. Wirtschaft, Politik und Gesellschaft, eds. Matthias Berg, Jens Thiel and Peter Th. Walther, Vol. 7, (Frank Steiner Verlag, 2009), 185.

[46] The hygienist Heinz Zeiss introduced a showpiece work of the new geomedicine (=spatial medicine) with his “Disease Atlas”. Especially in the Third Reich, geomedicine was extremely relevant in the Eastern campaign (spotted fever!). The Waffen-SS even had its own hygiene institute. In 1945 Zeiss’ treatise was expanded into the “World Disease Atlas”.

[47] Keith Neilson and Greg Kennedy, eds., The British Way in Warfare: Power and the International System, 1856 – 1956, edited by Royal Military College of Canada and King’s College London, (Ashgate Publishing Company, 2010), 157.

[48] Pascal Riemer, Von der russischen Kriegskunst. Eine Untersuchung der dialektischen Zusammenhänge von Staatsidee und Militärwesen am Beispiel der Sowjetunion und der Russischen Föderation, (Miles Verlag, 2021), 71.

[49] Markus Reisner, Die Schlacht um Wien 1945. Die Wiener Operation der sowjetischen Streitkräfte im März und April 1945, (Kral-Verlag, 2020), 13.

[50] Ibid., 15.

[51] Ibid., 17.

[52] Ibid., 63.

[53] Arnulf Scriba, “Die Schlacht bei Kursk 1943,” Deutsches Historisches Museum Berlin, September 25, 2022, https://www.dhm.de/lemo/kapitel/der-zweite-weltkrieg/kriegsverlauf/schlacht-bei-kursk-1943.html.

[54] Paolo Cau, Die 100 größten Schlachten. Sie haben die Welt verändert. Von Kadesch (1285 v. Chr.) bis heute, ( Kaiser-Verlag, 2007), 215.

[55] “The German Lighting War Strategy of the Second World War,” Imperial War Museum, https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-german-lightning-war-strategy-of-the-second-world-war.

[56] Victor Schunkow, Die Waffen der Roten Armee. Panzer 1939 – 1945, (Motorbuch Verlag, 2020), 70.

[57] Ren Hongpeng, “The Misuse of Sun Tzu and the Cult of Maneuver,” Military Strategy Magazine (Vol. 9), no. 4 (Summer 2024), 12-17.

[58] The landing manoeuvre on D-Day required well-prepared weather forecasts and maps, as well as manoeuvre training (Exercise Tiger in 1944).