Abstract: The longstanding relationship between terrorism and the scramble for resource poses significant challenges to global peace, which is contested time and time again. The activities of insurgent groups in the Sahel affect its inhabitants’ livelihood and human rights while worsening the pressure on the rest of West Africa – precipitating the Boko Haram scourge in Nigeria and attracting ISIS and ISWAP into the region.

Problem statement: What is the link between the drug trade, illegal mining, and the multinational firms co-existing in the Sahel region?

Bottom-line-up-front: Addressing the socio-economic and political causes of the insecurity in the Sahel has taken a hundred years. It is argued that poor governance fueled by foreign interest is responsible for insecurity in the Sahel.

So what?: Regional security organizations such as ECOWAS have the potential to enhance much-needed bilateral exchange among law enforcement and intelligence agencies to address the security threat. Likewise, countries implementing the UN global strategy against terrorism should considerably monitor the activities of multinationals and drug cartels in the Sahel to moderate the unease.

Source: shutterstock.com/Bumble Dee

The Sahel – An Unwitting Ground Zero

The Sahel region that encompasses northern Mali and northwestern Niger – often referred to as Azawad and mostly inhabited by Tuareg pastoralists – is a geopolitical epicenter in and of itself. It is an unwitting ground zero and staging ground for some of the most radical Islamic forces currently reshaping international and regional political order.[1] The balance of terror and the political realities of sub-Saharan Africa, especially Sahel geopolitics, arouse fear and worry. Of course, and on their own accord, canons, deep cultural beliefs, and fundamental core values are difficult to unlearn. Indeed, in Afghanistan, the Middle East, or South America, when old ways are disturbed, it is almost always a recipe for and often a stimulus that elicits rebellion and armed conflict.

The balance of terror and the political realities of sub-Saharan Africa, especially Sahel geopolitics, arouse fear and worry.

Like the Bedouins found primarily around Israel, Jordan, and Syria – the Tuareg of West African Sahara and Sahel, with an ancestry stemming from the Berbers, have lived for centuries in an environment that promoted lifestyle in an arid, harsh, and sparsely populated region, until the arrival of foreign interests in the late 1800s.[2] Europe’s advance into Africa suddenly quickened between 1880 and the first decade of the twentieth century, leading to the former’s acquisition of colonies and a means of obtaining raw materials and access to foreign markets.[3] The 1885 Berlin Conference was a turning point, leaving the Tuareg divided across Mali, Niger, Libya, and Algeria. The artificial boundaries and introduction of ungainly laws by the French broke up Tuareg’s economic structure, leaving them bewildered. Despite it metaphorically being too late in the day to dwell on acts that were inimical to common interests, it bears mentioning that former colonial powers threatened the safety of the common people without cause.

France is interested in securing oil and Uranium, which Areva S.A. (wholly owned by the French government),has been extracting for decades in neighboring Niger. Also, to give its activities some credibility, Paris sought shared responsibility when it urged a multilateral intervention with a few European countries, including Belgium.[4] Often and at the same time, African troops are sent to the front. Thus, sponsored terrorist activities overshadow the illicit mining of Uranium and other natural resources while frequently reinforcing one another. In fact, terrorists engage directly or indirectly in organized crime activities such as trafficking, smuggling, extortion, and kidnapping for ransom. The uprising in Saharan Africa is not particularly singular; yet, such conflicts are often localized and seldom spread far until they become interrupted by external events. This is the emphasis: it takes the French and their cohorts’ intervention for an escalation to occur on a large scale and spread further to other states.

On the Tuareg

The Tuareg first resisted colonial rule and later defied their inclusion in the postcolonial states. Furthermore, their wish for an independent state is full of reminiscence but also distinct in two ways. While secessionism is strong enough among the Tuareg of Mali and Niger to potentially result in armed rebellion, there has been no formal irredentism, as in no structural efforts to unite all Tuareg into one territorial state.[5]

While secessionism is strong enough among the Tuareg of Mali and Niger to potentially result in armed rebellion, there has been no formal irredentism, as in no structural efforts to unite all Tuareg into one territorial state.

Secondly, the ideal of national independence has never been raised in official negotiations with the states from which the Tuareg fought. From accounts, boundaries are non-existent and inconsequential to the Bedouins and the Fulani tribes across West Africa. Thus, it is highly likely that the restraints introduced by France were a proverbial watershed and major cause of conflicts in the Sahel region. Perhaps, even the beginning of armed resistance and the formation of the MNLA in northern Mali.

The Formation Of the MNLA

The National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) is ethnologically driven, and mainly fights for the rights of Mali’s minority Tuareg community. The MNLA – a successor to previous rebel groups – was formed in 2011. Hitherto, many Malian Tuareg had occupied Colonel Muammar Gaddafi’s military, a move that brought relief to an embattled Malian government which was troubled by the Tuareg’s militant affairs within its borders. After Gaddafi’s capture and killing in 2011, the Tuareg returned to Mali, bulging the ranks of the MNLA as it spearheaded an uprising against the Malian army. The Tuareg who were in Libya also brought weapons, including surface-to-air missiles. These returnees, thus, formed the MNLA in 2011 as the political-military platform to continue their fight for self-rule.

Though widespread across the Sahel, the Tuareg are about three million people; close to one million inhabit Mali alone. Following Mali’s independence from France in 1960, a series of droughts affected the northern cities of Timbuktu, Kidal, and Gao.[6] Being one of the Sahel’s least developed regions, the state of Mali failed to ensure holistic and inclusive development across all regions. In the end, the government ignored the northern part and now finds itself crushed by the ever-increasing weight of climate change.

Though widespread across the Sahel, the Tuareg are about three million people; close to one million inhabit Mali alone.

However, it is not only this occurrence that provokes the current feud. The Tuareg’s homeland has the largest energy deposits in Africa. Their dream of an independent state, separation from Mali, and the right to govern their own land, which they called Azawad, was escalated by the involvement of global superpowers scrambling for resources. Expectedly, the presence of the Western powers triggered the interest of Al Qaeda in the region. Thus, poor governance, Western interests and attraction of the Islamic fundamentalists incite passion and threaten the five neighboring states – a stake that has the potential to elicit a conflict in the Sahara similar to that of Afghanistan and the Middle East.

The Axis of Evil mantra is also consistent with the events in the Sahel. As Jihadists were displaced in another axis, Africa became the next safe haven. Until a few decades back, the French operated in the Sahelian without much trouble. Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Syria greatly influenced Algeria and Northern Mali. The Gulf Wars and subsequent revolutionary ideas in Libya undoubtedly echo the episodes in Northern Mali. Inadvertently, these affairs not only expatriated some Mujahedeen from Iraq and the Middle East region, they equally magnetized Islamic fighters from Afghanistan, Sudan and elsewhere into Azawad. In other words, Northern Mali and the Sahel region generally became an alternate and, to a large extent, a rallying point for the mujahedeen.[7] Yet, the internal debateswithin Al Qaeda’s hierarchy about the same period, concerning waning support for the Iraqi and Algerian insurgencies and the failure of Islamist revolutionaries, further stimulated the interest of hardened fighters to engage in Mali.

MNLA: Achievements And Failures

Tuareg fighters of Malian origin had departed Libya with great enthusiasm. They hoped to bring peace and affluence to the region and revive the dying pastureland – their only source of livelihood. Unfortunately, the meddling by more radicalized factions with alternate agendas subsequently dashed these expectations.

MNLA’s alliance with the Islamists collapsed. Ansar Dine and (Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa) MUJAO drove MNLA’s forces out of the main northern towns. The MNLA’s influence waned after it ran out of money, causing many of its fighters to defect to Ansar Dine and MUJAO. Albeit, Tuareg returnees had been part of Gaddafi’s mercenary army and returned to northern Mali with sophisticated weaponry – it was an exodus from profusion to despair, having experienced the wealth of Libya, and now suddenly being back in their home country that was beset with lack, famine, and disease; and most significantly: the non-existence of a central government.

Tuareg returnees had been part of Gaddafi’s mercenary army and returned to northern Mali with sophisticated weaponry.

Indeed, the Tuareg’s ambition was limited to overthrowing government control in the Northern sector. The Tuareg aimed to control their natural endowment to emancipate their population of one million from oppression. They equally perceived the central government as a willing tool in the hands of the imperialists, the French. However, the seemingly modest ambition to establish a home for the Tuareg people failed.[8]

What happened in Mali could be likened to the revolutionary activities that swept through America and resulted in the American Declaration of independence in 1776.[9] It was very succinct as to why the British colonies of North America sought independence in July of 1776.[10] What is remarkable in the American case is the opening preamble stating categorically that there are certain unalienable rights that governments should never violate. These rights include the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. The document went further to decree that when a government fails to protect those rights, it is not only the right but also the duty of the people to overthrow that government.[11] In its place, the people should establish a government designed to protect those rights.[12]

Pierre Boilley, a professor of Contemporary African History at the University of Paris, remarked that. “at the beginning, this was essentially a political movement, but with the return of the Tuareg from Libya, it became military as well as political”.[13] Colonel Meshkenani Ag Bela of MNLA, one of the fourth generations in his family to rise against Mali and its forerunner colonial friends, stated, “We have a deep-rooted and bitter history, we fought French imperial forces until they left. We never accepted French colonialism or when France gave our land to Mali without our consent.[14] And so by March 2012, just one year after the formation of MNLA, the Tuareg toppled the Malian government forces and declared the independent state of Azawad in what had been northern Mali. Analysts observed that the Tuareg MNLA and Islamist Ansar Dine rebel groups came together and pronounced northern Mali an Islamic state. In 2018, Ansar Dine began to impose Islamic law in Timbuktu, while Al-Qaeda in North Africa endorsed the deal.[15]

Challenges Of Azawad – Northern Mali

One of the reasons adduced by the MNLA while declaring its independence on April 06, 2012, was that Mali is an anarchic state. Therefore, they decided to put in place an army capable of securing their territory and an administrative office capable of forming democratic institutions. The general idea they were advocating for was a state of cultural, ethnic, tribal, and racial standing and nothing more than greater autonomy from the larger group, which is Mali. What was not apparent were the self-motivated and contending needs within the rank of the pugilist and extraterritorial influence.

The general idea they were advocating for was a state of cultural, ethnic, tribal, and racial standing.

Sociopolitical Triggers of Insecurity

Ab initio, when compared to Boko Haram (BH) in Nigeria, MNLA is differently structured. However, with the infiltration of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) into the BH activities in Nigeria, BH began assuming a different structure and dimension, like Al Shabab and the MNLA. What is fundamentally similar about the groups is the pervasiveness of violence, which has grabbed the world’s attention regarding their operations. As with the assessment of terrorism in Nigeria, three groups of theories are prominent. These are economic and social integration, resource mobilization, and cultural theories. Poor democratic culture, poor leadership and prevalent human rights abuses in Nigeria further bolster the theories.[16]

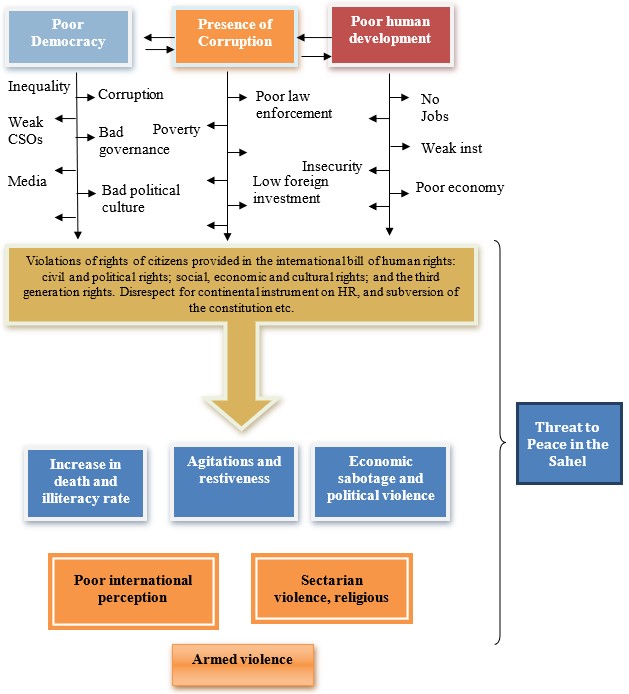

Threats to peace in Sahel; Source: Author

There are social, political and economic conditions that feed fundamentalism and intolerance, which make ordinary people susceptible to terrorist recruitment. They include poverty and hunger, lack of access to quality education, unemployment, political manipulation of religion by the elite class, and struggle over controlling state resources.

Election malpractices, poor governance and corruption abate in Mali also. The society is thus in a state where the majority are disenfranchised and marginalized. Ethnic and religious differences are also a veritable tool in the hand of politicians to settle their scores, leading to further uncertainty. In their establishment, the MNLA was out to redress perceived inequalities, restraints and a lack of responsiveness by their rulers.

Election malpractices, poor governance and corruption abate in Mali also. The society is thus in a state where the majority are disenfranchised and marginalized.

Observers were not astonished that Azawad could not succeed as expected, primarily grounded in sociopolitical and economic reasons. However, what has arisen from this failure and the current situation on the ground has become clearer under organizational characteristics and activities in Azawad. The Jama’at Nusra al-Islam wa al-Muslimeen (JNIM, also known as the Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims, or GSIM) has become a major concern not only in Northern Mali but across the Sahel. It is undoubtedly one of the world’s deadliest and most promising among those operating in the semi-arid Sahel region within the Sahara Desert and the South of it.

Network Of Terrorist Groups In the Azawad

The Azawad region appears as a cauldron of lawlessness and unrest, and it is difficult to clarify the complex situation that currently whelms the enclave precisely. Some may see it as a dangerous development, but for the jihadist, it seems thrilling. Clearly, Northern Mali is a diverse blend of religious fighters, ethnic militias and secularists.

There is the core MNLA that would prefer a secular and egalitarian regime. They seem to promote a political system in which the state has substantial and centralized control over social and economic affairs. Within the group, the fundamentalists seemingly do not share this view – a faction that can be classified as the Islamists. The Islamist faction among the group wanted to establish Islamic rule with an all-inclusive ultra-violent takfirist and sectarian strategy. Among this group were jihadists that owed their ideology to the Islamic state, including al-Qaeda, AQIM, and MUJAO.

Azawad And the Uprising In West Africa

Violence is currently tearing the Sahel apart and spreading across West Africa. It becomes important to ask who the armed groups behind the bloodshed are. Moreover, where are international actors stationed in the region? Much has been said about the AQIM and Ansar al-Din. However, as a primer to deeper analysis, it is significant to highlight that the AQIM is al-Qaeda’s North African wing, rooted in Algeria. One of the top commanders is the Algerian Abdelmalek Droukdel, also known as Abu Musab Abdel Wadoud. AQIM consists mostly of foreign fighters, focusing on spreading Islamic law, liberating Malians from the French colonial legacy, and raising its funding through drug trafficking and kidnapping.

MUJAO is an AQIM splinter group that formed in mid-2011. The split, essentially, was because AQIM’s method of jihad was unwieldy, and Arab commanders largely subjugated this cluster. From the beginning, MUJAO had a clear Sahelian orientation, framing that historically, jihads fought in the region during the 19th century and openly promoted the recruitment of Sahelian and sub-Saharan Africans. MUJAO controlled Gao but maintained contact with AQIM and Ansar al-Din during the occupation.

The Signed-in-Blood Battalion is essentially an offshoot of AQIM. The group was led by the Algerian Mokhtar Belmokhtar and had a strong alliance with Ansar Dine and MUJAO, who was part of the administration of Gao after MUJAO seized it. All these militants follow the Saudi-inspired Wahhabi/Salafi sect of Islam, making them unpopular with most Malian Muslims who belong to the rival Sufi sect.

From the beginning, MUJAO had a clear Sahelian orientation, framing that historically, jihads fought in the region during the 19th century and openly promoted the recruitment of Sahelian and sub-Saharan Africans.

After the 2011 killing of bin Laden, Zarqawi’s Iraq campaign was repeatedly criticized for its sectarian agenda and killing of Muslims.Thelate AQ’s American media advisor Adam Gadan was so concerned that AQ’s branches were hurting the parent organization’s reputation that he advocated ending links to its regional appendages.[17] Bin Laden lamented the near enemy focus of his affiliates and reproved the emirs of AQIM, AQI, AQAP and Al Shabaab for their improper execution of his brand of jihad. Meanwhile, in August 2013, MUJAO and its military command under the Gao Arab Ahmed Ould Amer (Ahmed al-Tilemsi, later killed by French forces) joined Mokhtar Belmokhtar’s Katibat al-Mulathimeen and Katibat Mouwaqun bi Dima (“those who sign in their blood”) to form al-Mourabitoun. Al-Mourabitoun is a reference to the Almoravid empire that burst forth from the Sahara in the medieval period and eventually conquered much of North Africa and Spain.

The MUJAO split in 2015, with part of the group’s fighters becoming the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara under Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahraouian. The rest remained with al-Mourabitoun, eventually joining Nusrat al-Islam, officially known as Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin’ (JNIM), a militant jihadist organization in the Maghreb and West Africa formed by the merger of Ansar Al Dine, the Macina Liberation Front, Al-Mourabitoun and the Saharan branch of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb.

One al-Mourabitoun leader was part of JNIM’s founding group, Hassan al-Ansari, an Arab fighter from the Tilemsi valley north of Gao. He was killed near the Algerian border by French forces in February 2018, along with a few other important figures from JNIM. Al-Mourabitoun has carried out some of AQIM’s and JNIM’s larger-scale attacks. The group, led by Iyad Ag Ghaly, specializes in complex attacks on soft targets. They include the following attacks: Radisson Blue hotel in Bamako (November 2015), the Cappuccino Café and HOTEL TK in Ouagadougou (January 2016), and Grand Bassam in Côte d’Ivoire (March 2016). Nevertheless, the group has also targeted hardened military bases, like the attack on the Mécanisme Opérationnel de Coordination (MOC) in Gao in January 2017, which killed dozens of people.

The MUJAO split in 2015, with part of the group’s fighters becoming the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara under Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahraouian.

Three categories describe the recent events in Mali: Reason, Action and Outcome. The Tuareg have reasons for seeking an independent Azawad, but multiple engagements in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Syria inflame and obfuscate a localized civil uprising. Furthermore, the most probable outcome is becoming evident – tearing West Africa into shreds. Nigeria, though remote, has been destabilized as a corollary of these engagements. Gaddafi’s overthrow forced thousands of his Malian-Tuareg mercenaries back to their home country and gave the impetus to irredentist and separatist passions. Having failed in prior insurgencies against the central government in Bamako, Tuareg rebels found their capabilities enhanced by the flow of mercenaries and their advanced Gaddafi-era weapons. Again, political freedom and economic opportunities are not widespread in Northern Mali, leading to an upshot of terrorist activities in Niger, Chad, Nigeria and other West African states.

Involvement In Criminal Activity

Besides the relationship between criminals and terrorists and their activities, the structure of MNLA or AQIM and their logistical requirements also warrant further scrutiny. There is no gain in downplaying the notion of a nexus between criminality and terrorism. However, it is difficult to concede under certain conditions that terrorists and criminals would cooperate for mutual benefit. Again, there are many factors responsible for this state of affairs. For instance, in the geopolitical environment of the Sahel, poor governance, prolonged marginalization or persecution by the state (including perceived), and longstanding ethnic or nationalist discord may create opportunities for geographic vulnerabilities. Lack of legitimate opportunities for social advancement, chronic or perceived inequality and the failure of state service delivery could further incite organized crime.

Though drug trafficking and its use ensued in Mali long before the emergence of MNLA or AQIM, the global initiative against transnational organized crime claims that illicit trafficking defines the nature of the Malian crisis and has led to the militarization of the Sahelian protection economy. Of course, drug cartels in West Africa buy more than real estate, banks and businesses; they buy elections, candidates and parties, and power.[18] Since the French and UN intervention in 2013, counternarcotics policy reform debates in Northern Mali have wrongly focused on the theory that jihadists may be in control of the drug trade in Mali and the wider Sahel. Yet, this conviction is attributable to the dismal success of Mali counternarcotics and drug use prevention operations. The Malian government and UN officials within the country seem to be less excited by the premise that jihadists may be controlling the drug trade and consequently making millions of dollars.[19] There is, however, some level of government involvement in the business of illicit drug trade in Mali.

Since the French and UN intervention in 2013, counternarcotics policy reform debates in Northern Mali have wrongly focused on the theory that jihadists may be in control of the drug trade in Mali and the wider Sahel.

It is difficult to exonerate government institutions in Mali. At the same time, drugs are moved brazenly from adjourning states by road and transported under escort through the desert to destinations further north towards Europe.[20] For instance, government ministers and senior army and intelligence officers close to President Touré are believed to have been involved in the infamous crash landing of a Boeing 727 in Tarkint (near Gao, Northeast Mali) on November 2, 2009, which had originally come from Venezuela and carried an estimated five to nine tons of cocaine.[21] The jet was reported to have first successfully landed on a makeshift airstrip about nine miles from Gao, in an area controlled by Tuareg and Islamist insurgents. It later crashed under suspicious circumstances and was then torched by the traffickers. President Touré described the incident as a threat to Mali’s national security but did not call for an official investigation into the matter until three weeks later.[22] It appears that romance with drug activities in the highest levels of governance emboldened the terrorist organizations in Northern Mali, particularly AQIM, to become deeply involved in drug trafficking activities in the Sahel.[23]

By 2012, MNLA influence had waned, as seen in the loss of territories and influence to AQIM. Consequently, AQIM and ally Islamist group Ansar Ed-dine imposed a regime of despotism within the north that included extrajudicial killings, the obliteration of historical monuments in Timbuktu, and the subjugation of women. David Brown, previously the Senior Diplomatic Advisor at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, revealed that illicit drug trade provides tens of millions of dollars, which terrorists use to finance their operations in the Sahel.[24]

Wolfram Lacher, an expert on North Africa at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin, contended that the drug trade is just one of a range of illicit activities in which they engage; and that the existence of a “drug-terror nexus” in West Africa and the Sahel, on the scale that it has been reported, is misleading. Lacher reasoned that the drug trade was more of an individual and their cohorts, driven by multiple and, at times, conflicting motivations.[25] It was also reiterated that members of the political and business establishment in northern Mali, Niger, and the region’s capitals, as well as leaders of supposedly ‘secular’ armed groups are complicit. Thus, an emphasis on narco-jihadism. Lacher’s prognosis obscures the role of state actors and corruption in allowing organized crime to take root and grow”.

Drug trade is just one of a range of illicit activities in which they engage; and that the existence of a “drug-terror nexus” in West Africa and the Sahel, on the scale that it has been reported, is misleading.

On one occasion, the concept note prepared by France for the December 2013 UN Security Council debate on drug trafficking and transnational organized crime stated that violence in Mali by criminal networks attempting to control the drug trade fostered radicalization. It was based on the premise that those radicalized individuals participate in the drug trade. The concept note stated, “Cocaine and cannabis trafficking enables extremists to generate income, which in turn finances rebellions” (Report of the Security Council, 2014). Compellingly, global interest concerning anti–drug agenda in the Sahel would only align upon reduced complicities among the multinationals operating in Northern Mali and political corruption by the region’s governments.

Strategic Shifts And Trajectory In the Sahel

Today’s situation differs from the crisis that erupted in 2012, when a Tuareg group, the MNLA allied with Ansar Dine and the MUJAO to fight for an independent state in northern Mali. The fronts have since shifted due to external influence. For instance, Ansar Dine – full name in Arabic being Harakat Ansar al-Dine, which translates as “movement of defenders of the faith” – is seen as a homegrown movement. A renowned former Tuareg rebel leader Iyad Ag Ghali, whose objective is to impose Islamic law across Mali, led the Ansar Dine. The militant groups that were chased out from the major towns by the French ‘Operation Serval’ in 2013 dispersed, reorganized and spread. The first spread of militant groups was from northern Mali to central Mali in early 2015 (under the impetus of the Macina Liberation Front); the second was in late 2016 to western Niger (mainly the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) and northern Burkina Faso (Ansarul Islam – a local Burkinabe group with links to Al-Qaeda); the third expansion of militant groups took place in early 2018, to eastern Burkina Faso where all groups (JNIM, ISGS and Ansarul Islam) have established bases.[26] The fourth wave will likely see militant groups expanding their reach to Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Togo and Benin.

The first spread of militant groups was from northern Mali to central Mali in early 2015; the second was in late 2016 to western Niger; the third expansion of militant groups took place in early 2018 to eastern Burkina Faso where all groups have established bases.

Undoubtedly, the JNIM is one of the world’s deadliest and most promising terror organizations. The group operates at the fringes of the semi-arid Sahel region south of the Sahara Desert that is poorly governed. The security situation in the Sahel is therefore worsening. The region experienced a massive spike in deadly violence in the first half of 2019 as the militant groups continued their expansion southward, now threatening coastal West Africa.[27]

Azawad Movement And Geopolitics Of Mali

The Azawad movement ended in 2013 when the Malian government and the Coordination of Azawad Movements (CMA) signed the Algerian-brokered peace deal. According to the agreement, the CMA would respect the “unity and territorial integrity of Mali”. Instead of one single elected assembly, Azawad would have five, one for each of the area’s regions: Timbuktu, Gao, Kidal, Taoudeni and Menaka. The last two were to be newly created. The agreement also provided increased representation of Azawad’s regions in Malian state institutions, along with greater economic investment. Remarkably, the promises from Mali for greater political autonomy for the Tuareg in the north have never materialized. As a result, the Malian government has failed to foster a trusting relationship with the Tuareg.

Perspectives On Azawad

The issues in Northern Mali are not as complex as presented by most writers on the subject matter. Indeed, authors are most guilty of increasing ambiguity about the narratives in Mali, Congo (DRC), and larger Africa. According to Malik Ibrahim, US-American planners are well aware that their local partners frequently fuel the very forces that foster violent extremism and instability through their authoritarian governing styles.[28] Malik quickly suggested that Mauritanian President, Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz, pushed his monopolization of political power when he abolished the country’s senate. Thus, on the one hand, it can also be argued that poor governance fueled by foreign interest is responsible for insecurity in the Sahel.

On the other hand, groups that migrated to the region and far beyond have governed Mali interchangeably. Furthermore, for decades, researchers and authors have willfully ignored the fundamentals in Mali. This article concludes that the time is now to establish a theoretical linkage between human rights protection, justice and peace in Northern Mali. The capacity of the USA and its European allies to make Mali great again is not in doubt. Germany and Japan were renewed after the Second World War through the Marshall Plan, a joint effort between the USA and Europe based on the idea that Maoism succeeded only in countries with economic problems. Similarly, terrorism thrives in extreme poverty.

The capacity of the USA and its European allies to make Mali great again is not in doubt.

The threat is on the rise in North Africa and the Sahel, but not yet out of control, said Jean-Pierre Filiu, a professor at the Paris Institute of Political Studies (Sciences Po, Middle East department) and the author of Apocalypse in Islam.[29] Now is the right time to conclude and end the duplicity in Northern Mali.

Kunle Olawunmi; National and International Security Studies; Earlier Publications: COVID-19: Ensuring Continuity of Learning During Scholastic Disruption in Tertiary Institutions in Nigeria, World Journal of Education, 2021; BIO-TERRORISM, IMPERIALISM AND HEMORRHAGIC FEVER EBOLA VIRUS, Academic Journal of Current Research, 2019; Nigeria, Global Peace, and International Protection of Human Rights Comparative and international political science LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing (2019-05-17) -ISBN-13: 978-620-0-09293-9; Department: Criminology and Security Studies, Intelligence, and Terrorism. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of Chrisland University, Abeokuta, Nigeria.

[1] Climate Diplomacy, “Tuareg Rebellions in Mali and Niger in the 1990s,”

[2] Andrew Alesbury, “A Society In Motion: The Tuareg From The Pre-Colonial Era To Today, White Horse Press,” Vol. 17, No. 1, Special Issue: Securing the Land and Resource Rights of Pastoral Peoples in East Africa (2013), 106-125, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43123923.

[3] Thierno Bab, “Colonial Imperialism: The Partition Of Africa at the 1885 Berlin Conference and its Consequences For African Muslims,” https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000260317.

[4] Rachel Baig / gsw, “French interests in Mali,” January 16, 2013, https://www.dw.com/en/the-interests-behind-frances-intervention-in-mali/a-16523792.

[5] Lecocq and Klute, “Tuareg separatism in Mali,” February 10, 2023, https://journals.sagepub.com/home/IJX.

[6] Abhijit Mohanty, “Mali Crisis: A Historical Perspective of the Azawad Movement,” retrieved May 30, 2020, https://www.geopoliticalmonitor.com/mali-crisis-a-historical-perspective-of-the-azawad-movement/.

[7] Merise Jalali, “Tuareg Migration: A Critical Component of Crisis in the Sahel,” https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/tuareg-migration-critical-component-crisis-sahel.

[8] Abhijit Mohanty, “Mali Crisis: A Historical Perspective of the Azawad Movement,” https://www.geopoliticalmonitor.com/mali-crisis-a-historical-perspective-of-the-azawad-movement/.

[9] “Declaration of Independence broadside, July 1776, Jamestown – Yorktown Foundation,” (1775), America’s Declaration was written by Thomas Jefferson and adopted by the Second Continental Congress at the time.

[10] K. Olawunmi, “Nigeria, Global Peace and International Protection of Human Rights

LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing,” 1–3, (May 17, 2019).

[11] The Declaration of Independence, 1776, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1776-1783/declaration.

[12] Declaration of Independence broadside, July 1776, Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation, (1775).

[13] Idem.

[14] Idem.

[15] “Mali profile – Timeline,” 2018, 2.

[16] K. Olawunmi, “Nigeria, Global Peace and International Protection of Human Rights,” (1st ed., Vol. 1), Mauritius, Mauritius: Lambert Academic Publishing.

[17] N. Lahoud, S. Caudill, and D. Rassler, “Letters from Abbottabad: Bin Ladin Sidelined?,” West Point, United States: Combating Terrorism Center, 1–3.

[18] L. Gberie, “State Officials and their Involvement in Drug Trafficking in West Africa,” February 24, 2017, WACD Background Paper No. 51, retrieved January 11, 2022, http://www.globalcommissionondrugs.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/State-Officials-and-Drug-Trafficking-2013-12-03.pdf.

[19] Idem.

[20] L. Gberie, “Crime, Violence, and Politics: Drug Trafficking and Counternarcotics Policies in Mali and Guinea,” January 05. 2018, retrieved June 01, 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Brookings-Crime-Violence-and-Politics-Drug-Trafficking-and-Counternarcotics-Policies-in-Mali-and-Guinea.pdf.

[21] “Not Just In Transit:Drugs, the State and Society in West Africa An Independent Report of the West Africa Commission on Drugs,” June 2014, https://www.unodc.org/documents/ungass2016/Contributions/IO/WACD_report_June_2014_english.pdf.

[22] “Drugs and Tugs” Africa Confidential, Vol. 50 No. 24, December 04, 2009, https://www.africa-confidential.com/article-preview/id/3337/Drugs_and_thugs.

[23] A. Abderrahmane, “Drug Trafficking and the Crisis in Mali,” August 06, 2012, retrieved May 25, 2022, http://www.issafrica.org/iss-today/drug-trafficking- and-the-crisis-in-mail.

[24] David Brown, Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, retrieved June 01, 2022, 1-3, www.jstor.org/stable/resrep11261.

[25] W. Lacher, “Organized Crime and Conflict in the Sahel-Sahara Region,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 5, https://carnegieendowment.org/2012/09/13/organized-crime-and-conflict-in-sahel-sahara-region-pub-49360.

[26] F. Berger, “West Africa: shifting strategies in the Sahel,” IISS, 2, retrieved from https://www.iiss.org/blogs/analysis/2020/10/csdp-west-africa-sahel.

[27] Idem.

[28] Malik Ibrahim, “America’s Self-Defeating Sahel Strategy,” OPINION, October 26, 2017, https://www.geopoliticalmonitor.com/americas-self-defeating-sahel-strategy/.

[29] Jean-Pierre Filiu, “Apocalypse in Islam,” (University of California Press, 2011).