Abstract: There is a plethora of studies on suicide terrorism from different aspects, but researchers have failed to identify suicide attacks as a weapon of choice. This reluctance may stem from the fact that suicide terrorism does not fall under the strict terminology of ‘weapon’. Suicide attacks have been used as a weapon to accomplish both hard and soft targets. To carry out a suicide attack, gender has not been a barrier. A suicide attack may not fall under the strict interpretation of a weapon. Still, it can be used as a weapon to accomplish a target, subject to the availability of the so-called resources of suicide bombers.

Problem statement: Under what circumstances is suicide terrorism considered to be a weapon of choice?

So what?: Policymakers need to understand the pull and push factors that relate to becoming or not becoming a suicide terrorist and take multidimensional approaches, including political, social and economic reforms, to prevent people from being converted to human bombers.

Source: shutterstock.com/Antonio Gravante

New Approach to Define a ‘Weapon’

In the legal context, as defined in Black’s Law Dictionary, the word weapon captures an instrument that is used to injure or kill a person or any device that can be used to attack or defend in combat. This includes items such as knives or any other device that can be used to inflict bodily harm. When perusing the literal meaning of weapon, it is observed that the said meaning of weapon has concentrated on a device. This research explores the possibility of expanding the definition of a weapon beyond devices. There is a rise in the popularity of suicide terrorism worldwide, but little evidence remains to understand whether suicide terrorism falls under the interpretation of a weapon. This research aims to understand whether suicide terrorism can be considered as a weapon and, if so, under what circumstances. It is also observed that terrorist organisations and small cells use suicide terrorism to accomplish their targets. When perusing the organisational structure, the terrorist organisations have structured organisational patterns, while small cells are organised in an unstructured manner. As such, it is interesting to know whether there is any difference in deploying suicide attacks by terrorist organisations and small cells.

Suicide Terrorism

In this research, the words suicide bombing and suicide terrorism will be used interchangeably. Yoram Schweitzer[1] defines suicide terrorism as “a politically motivated violent attack perpetrated by a self-aware individual (or individuals) who actively and purposely causes his death through blowing himself up along with his chosen target. The perpetrator’s ensured death is a precondition for the success of his mission.” Similarly, Horowitz[2] defines suicide terrorism as “an attack where the death of the bomber is how the attack is accomplished.” What is common in both definitions is that, in suicide terrorism, the target is predetermined, and it is about to be achieved through sacrificing the life of the executor.

…an attack where the death of the bomber is how the attack is accomplished.

Understanding what drives a person to sacrifice their life to achieve a target is worthwhile, and why it cannot be achieved through other means. Studies on suicide terrorism are diverse,[3] but there are common perceptions on why suicide terrorism is used on an organisational or individual basis. Suicide bombers can act as smart bombs or clever bombers because of their thinking ability. Smart bombers can deviate from the original plan if necessary to cause greater damage or to evade detection by law enforcement authorities. Bombs that are implanted or controlled remotely do not offer this benefit.[4]

Research has revealed that suicide terrorism has not been carried out for personal gain but to achieve a public good: independence, nationalism, religious belief or a political goal.[5] The gain of public goods by sacrificing one’s life was affirmed by Ward,[6] stating that suicide bombers in Sri Lanka, Afghanistan and Iraq were not paid. However, this is not the case with Palestinian suicide bombers, as Palestinian families have received monetary gain after the death of the family member who executed a suicide attack.[7]

To continue the discussion on understanding why (or why not) people become suicide terrorists, most researchers have focused on answering this question by trying to understand the root causes of suicide terrorism.[8] As proposed by Horowitz, it is difficult to find the root causes of suicide terrorism as suicide bombers come from different types of communities, from different situations, times, and spaces. What is important in this context is that, irrespective of the cause of motivation, such as whether to achieve a public or private good, or to commit suicide, the militant has chosen the best method to accomplish their target. Put differently, regardless of the motivation, suicide bombing has been identified as the best mode of operation to reach their target.

As revealed in interviews conducted by Nasra Hassan[9] with prospective suicide bombers and the family members of the successful suicide bombers, the suicide bombers are educated and hardly poor. The level of education suicide bombers possess could be another benefit of suicide attack deployment. Since educated people can find ways to finance terrorist activities through their education, they do not need money for their military operations, which makes the degree of education and its relationship to suicide bombers significant. The law enforcement authorities might not notice if professional or educational abilities meet the financial criteria. However, to obtain this advantage, either educated or skilled individuals must be radicalised into becoming suicide bombers, or those chosen to carry out suicide bombing must receive the appropriate education or vocational training to become skilled assets. Azam[10] asserts that most suicide bombers have postgraduate degrees. It is safe to conclude that Azam is referring to the level of education of suicide bombers in general because he did not clarify whether or not the suicide bombers were affiliated with a terrorist organisation while discussing their educational backgrounds.

However, according to Sprinzak,[11] the educational background of suicide bombers may not be a significant factor when they are used by terrorist organisations such as the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Azam’s findings are important because they demonstrate how education changes people’s views on public goods, such as freedom and independence, and provides access to lucrative employment opportunities. There is a cost in executing terrorist attacks, and how terrorist organisations and small cells meet these costs is different. When terrorist organisations execute terrorist attacks, members of the terrorist organisation don’t need to bear the expenses, as they may have external parties or donors to provide the funding. In a small cell, when they form and plan to carry out terrorist attacks without an affiliation to a terrorist organisation, it is necessary to consider how they bear the expenses for terrorism; therefore, the educational attainment of the members and their earning capabilities are essential factors that need to be considered.

The educational background of suicide bombers may not be a significant factor when they are used by terrorist organisations such as the Kurdistan Workers’ Party.

In this research, suicide bombing has been analysed from a different point of view to understand its role as a weapon of choice. It raises intellectual curiosity as to why suicide bombing has become one of the best options or the only option to accomplish a target. For this purpose, suicide bombing as the modus operandi to accomplish a target has been analysed mainly under two limbs: (1) from an organisational perspective and (2) from an individual perspective. From an organisational perspective, it is a known fact that suicide squads were maintained, and these squads are an integral part of achieving the objectives of the organisation.

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) maintained a suicide squad, known as the Black Tigers. Black Tigers were highly trained professional soldiers tasked with accomplishing a specific target as part of winning the war.[12] Sprinzak states that to be selected for the Black Tiger squad, the terrorist needs to demonstrate their ability and devotion during the tough military selection program. However, this level of motivation and devotion does not apply to all suicide attackers. The PKK, as an example, recruited young women with no special professional skills as suicide bombers. In contrast to the terrorist organisations, such as Palestinian Hamas and the PKK, the LTTE tended to plan more suicide attacks with their suicide squad, namely the Black Tigers. This illustrates that, although suicide terrorism may be economically advantageous, it also has drawbacks, such as the difficulty in finding sufficient resources (suicide cadres or hardcore terrorists).[13]

Suicide bombing has also been used by small cells, and it is believed that these small cells adopt the self-starter phenomenon. First, the ISIL followers adopt the self-starter phenomenon to promote global Jihadist ideology. Kirby[14] refers to the self-starter cells as “groups that have little or no affiliation with the original Al-Qaeda network, made up of individuals who have never attended a formal terrorism training camp and whose attacks occur seemingly spontaneously, without orders from a number of the known Al-Qaeda leadership.” Kirby’s research was based on the London bombers; therefore, the self-starter phenomenon was interpreted using Al-Qaeda as an example. What is important with the self-starter phenomenon is operational autonomy. When terrorists operate spontaneously, there is no obligation on the main organisation to fund the unaffiliated terrorist attacks. The attacks in the formation of self-starter cells do not create a financial burden on the terrorist organisation.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

Money is a limited resource; therefore, it is equally important to understand not only why people commit suicide terrorism but also the cost-benefit analysis of suicide terrorism. From an economic perspective, suicide bombing is less expensive than other forms of terrorist activities. As an example of a battle, the weaker side has employed suicide terrorism as a method to counterbalance the imbalance caused by a powerful adversary, the state army.[15] For instance, the LTTE deliberately uses the Black Tigers to compensate for their military shortfall against government forces and to carry out difficult tasks, such as the killing of very important persons (VIPs), without having the burden of organising and funding an escape plan. Suicide terrorism, therefore, may be successful in reaching hard targets as it reduces the cost of financing terrorism since it eliminates the need for post-operation support, such as carrying out an escape plan that would involve creating fake passports and visas and offering lodging. The LTTE used suicide terrorism not only to reach hard targets, but also soft targets, such as unarmed civilians.

The weaker side has employed suicide terrorism as a method to counterbalance the imbalance caused by a powerful adversary, the state army.

According to several research studies on the subject, suicide terrorism is cost-effective and advances the goals of the terrorist organisation. However, this is not the case with small cell members and lone actors. As explicit in the Easter Sunday attacks and the London metropolitan attacks, the suicide missions were carried out by small cells targeting unarmed civilians, and they also executed the terrorist attacks by wearing backpacks filled with explosives that are freely available in the market for commercial purposes. Both terrorist organisations and small cells use suicide terrorism for unarmed civilians, and it is necessary to know why they target unarmed civilians. Suicide bombers target unarmed civilians to spread fear.[16] On this premise, suicide terrorism seems to be inexpensive to deploy attacks to reach targets where situational crime prevention methods raise the bar and spread fear among society.[17]

Suicide terrorism seems to be inexpensive to deploy attacks to reach targets where situational crime prevention methods raise the bar and spread fear among society.

Sprinzak’s research has focused on terrorism and neglected how these suicide attacks were financed. Previous research on money laundering has identified the rational launderer, who may possess knowledge and skills in technical expertise gathered through their criminal career.[18] There is no such research done on the part of terrorist financing to identify whether terrorists need any special skills or expertise to handle the economic resources to manage funding for their terrorist activities. Since the knowledge of terrorist financing is limited, it is difficult to understand the potential terrorists who could finance their terrorist activities.

Rationale

It is important to understand what might be the rationale for deploying suicide attacks from an economic perspective. This includes understanding how a terrorist organization or a small cell makes a (rational) decision to carry out a suicide attack under the scarcity of sources of funding. To understand the justification for committing suicide terrorism, it is necessary to analyze the scenario through the lenses of criminological theories. Criminological theories that explain crime illuminated from situational or environmental circumstances have limited application to the offence of terrorist financing, as these theories discuss preventing or reducing the capabilities to commit crime: terrorism. The applicability of rational choice theory depends on how the terrorist asserts rationality in a particular situation.

Since terrorist groups encompass diverse ideologies, the rational choice theory explains the micro aspect of the unitary actor. Rather than building a holistic model for criminal disposition, rational choice theory asserts that offenders choose specific crimes for specific reasons.[19] This answers the question of why some attacks were executed in the form of suicide terrorism. Policy papers such as FATF[20] discuss terrorist financing as a separate subject, but it is observed that terrorist financing always combines with terrorism. Terrorists employ various methods to finance their activities, and the amount of funding required to accomplish them varies according to the specific case. As an example, there is a difference between the amount of money needed for knife attacks and the 9/11 attacks.[21] To overcome this difficulty, a case-by-case analysis is necessary to understand how terrorists think to finance their activities, whether they act rationally, irrationally, or with bounded rationality.

There is a debate in the literature about whether rational choice theory can be applied to understand the offence of terrorism. This is based on the premise that rational choice theory is developed to explain conventional crimes. Becker’s[22] application of rational choice theory is limited to explaining crime from an economic perspective. Within this context, committing a crime is based on an exogenous element: the pursuit of profit with minimal losses. Paternoster et al.[23] expanded the application of rational choice theory from self-interest to test other-regarding preferences, including spiritual or emotional attachment and concerns for others. Studies conducted to analyse self-serving motivation are subject to limitations in collecting empirical data. Paternoster et al.’s study is based on a sample of undergraduate university students; therefore, it is doubtful how far the research findings can apply to a terrorist/terrorist financier.

There is a debate in the literature about whether rational choice theory can be applied to understand the offence of terrorism.

In conventional crimes, it may be easier to explain human behaviour through their choices, such as personal enrichment and monetary benefits, but this is more complex in the case of terrorism. The terrorist/terrorist financier may be motivated by either exogenous (peer pressure) or endogenous factors (religious beliefs, self-glorification, and self-esteem). Durkheim disagreed with explaining crime, religion or any other social factor through a psychological perspective, as empirical findings and conclusions were detached from personal beliefs about God.[24] According to Durkheim, it is necessary to understand the social conditions and circumstances that lead to committing a crime or a type of crime.

The common social phenomenon of committing a crime, such as unemployment, poverty, or drug addiction, has limited application to terrorism. When it comes to suicide bombers, they possess a high level of education and secure a rewarding future.[25] Azam pointed out that these suicide bombers are educated in Western countries, mostly in technical or engineering disciplines and ruled out that poverty and unemployment breed terrorism. Kis-Katos et al.[26] Criticise the literature on terrorism, stating that these studies consider all terrorists’ acts equally, irrespective of the heterogeneity of these terror groups and their different ideologies.

The concept of cost-benefit analysis from rational choice theory can be applied to terrorism; however, this calculation varies according to the nature of the crime, including the expected cost and expected benefit.[27] Further, it can be observed that the cost-benefit analysis of the terrorist and the terrorist financier may not be the same, as they have different objectives. The cost-benefit analysis of the terrorist may be based on the target selection, such as the country of location, the type of target, the frequency of the events and the methods used to achieve these targets against the expected benefit: unleashing terror and drawing public and political attention.[28] When it comes to terrorist financing, the terrorists’ targets incur a cost and need money. The cost-benefit analysis needs to explain the cost of committing a specific attack (such as a suicide bombing) or regular attacks (to control a territory) and the modes of financing, subject to the minimum risk of seizure, freezing, and confiscation of monetary assets.

The concept of cost-benefit analysis from rational choice theory can be applied to terrorism.

As an example, Sandlera and Enders[29] state each terrorist activity has a per-unit price that includes the “value of time, resources and anticipated risk to accomplish that act.” Based on these circumstances, to accomplish an act, a terrorist financier must consider the modes of financing. This includes financing their terrorist activities or through external sources: legal, illegal or both. Furthermore, the terrorist financier must devise a method to transfer money to the ultimate recipient. When analysing types of terror attacks, it is observed that some forms of attacks align with both the cost-benefit analysis of terrorists and terrorist financiers. As an example, suicide bombing is used as a promising method to face a trained state army with sophisticated weapons.[30] Further, suicide bombing requires less funding, as it does not need money to arrange alternative methods or finance escape plans. There are other options where terrorists can go for lethal attacks with minimal or no funding at all. In 2016, the Nice attack, in France as an example, was carried out by a lorry driver and killed 84 people.[31] These facts underscore the need for a case-by-case application of the cost-benefit analysis rather than a blanket approach to terrorism as a whole.

The ability of an individual to act rationally to maximise utility has been criticised in the academic debate on several grounds.[32] These arguments may hold valid with the rational thinking of the terrorist financier. To overcome the constraints of the traditional theory, the concept of the terrorist financier needs to be evaluated in light of the developments in rational choice theory. Firstly, Becker argued that an offender is motivated to commit a crime by the exogenous element of profit.[33] In contrast, van Um states in advanced rational choice theories, the motivation is not limited to a single factor, and it can be derived from political, economic or any other factor.[34] Secondly, rational choice theory states that people need to be motivated to commit a crime. Yet, personal variables and a range of human behaviours cannot be summarised into a set of predetermined parameters. The properties that may offend may vary according to motivation, ability, experience, expertise, and personal preferences.[35] Thirdly, there is a lack of research focusing on terrorist financiers and their ability to maximise utility.

Kahneman,[36] van Gelder,[37] van Gelder and de Vries,[38] and Pogarsky et al.[39] extend the cost-benefit analysis of the rational choice theory by integrating emotions into the decision-making process: hot (fast) or cool (slow). Emotions were considered not to eliminate the notion of a calculation of an offender but as a plausible explanation of how a criminal choice can be influenced through feelings and provide a realist view of the criminal decision-making process. All these studies share the common perspective that the norm of human nature is effortless thought (fast thinking), which comes into the mind spontaneously and effortlessly, but slow or cool thinking needs conscious, deliberate, cognitive reasoning. In contrast, Shiloh et al.[40] propose that when analysing the dual process of thinking, individual differences were not given attention, and therefore, it is difficult to generalise that one mode of thinking is more applicable to heuristic processing than the other. Theoretical perspectives, although they predict criminal behaviour successfully, there are gaps between the findings of the dual process of thinking and its applicability to serious criminal offences. For example, empirical studies on the role of feelings in criminal choice are based on a wide array of criminal acts, and most of these offences fall under the category of trivial or everyday affairs.[41] The data relating to suicide bombings were classified under the subheadings of year, purported target, modus operandi of the attack, and gender of the suicide bomber.

The data relating to suicide bombings were classified under the subheadings of year, purported target, modus operandi of the attack, and gender of the suicide bomber.

Methodology

This research has analysed data related to suicide terrorism that took place in Sri Lanka from 2000 to 2020. Thereafter, content analysis was done to understand the rationale behind suicide terrorism with the application of the rational choice theory. Sri Lanka has been selected based on the extensive use of suicide terrorism and also the suicide bombings that the LTTE influenced other terrorist groups, mainly carried out. The tactics used by the LTTE in their suicide missions were studied and copied. The data was extracted from the Global Terrorism Index, a publicly available database maintained by the University of Maryland. Accordingly, 64 incidents have been reported as suicide bombings over 20 years. The Sri Lankan government entered a ceasefire agreement with the LTTE on 22 February 2002.[42] Section 1.2 of the said agreement states that “neither party shall engage in any offensive military operation. This requires the total cessation of all military action …”. The government of Sri Lanka declared that it would abolish the ceasefire agreement on 4 January 2008, and the notification came into effect on 16 January 2008. Even though there was a ceasefire agreement in operation, the LTTE had launched suicide terrorist activities, including other military operations, from 2002 to 2008.

The data relating to suicide bombings were classified under the subheadings of year, purported target, modus operandi of the attack, and gender of the suicide bomber. Further, data relating to suspected terrorist organisations have also been recorded. When classifying data, incidents were taken into consideration rather than the number of suicide bombers involved in a particular incident. As an example, it was revealed that 14 militants were engaged in a suicide mission to launch the attack targeting Bandaranaike International Airport. For this research, the incident of attacking Bandaranaike International Airport was taken as one event, even though 14 militants were engaged in the said suicide mission.

The data relating to suicide bombings were classified under the subheadings of year, purported target, modus operandi of the attack, and gender of the suicide bomber.

While collecting data, there was an ambiguity about whether certain scenarios could be taken as suicide bombings. One such scenario is when militants blow themselves up before reaching the target, which can be taken as a suicide bombing. In this research, the said situations were taken as a suicide bombing even though the militant was not able to accomplish his target. Still, based on the modus operandi, the militant was about to deploy a suicide attack. In the second scenario, some militants consume cyanide to avoid detention by law enforcement authorities. This category was not taken as a suicide mission, as the modus operandi of the attack was not deployed like a suicide bombing. Consuming cyanide is more a part of the escape plan than accomplishing the target. It is warranted that if there is no life threat, the militant will not consume cyanide.

Data Analysis

Data relating to suicide attacks in Sri Lanka can be mainly categorised into two categories, based on their affiliation with the terrorist organisation or not. In the first category, suicide attacks were carried out as per the commands given by the terrorist organisation, namely the LTTE. The Sri Lankan Government proscribed the LTTE on 26 January 1998. The delisting of the LTTE came into effect on 4 September 2002, followed by the entry into a ceasefire Agreement with the Sri Lankan government and the LTTE. The ceasefire agreement was in operation until January 2008; thereafter, the Sri Lankan government discontinued it. From 2000 to 2009, the suicide attacks were carried out as per the instructions given by the LTTE. It could be inferred from the research findings that the suicide attackers had only to follow the commands and reach the target. In contrast, the financing, training, providing equipment such as suicide vests, and background information to reach the target were provided by the terrorist organisation.

Even to accomplish certain attacks, the terrorist organisation has deployed more than one suicide bomber. Based on the records, it was revealed that the LTTE deployed fourteen suicide bombers to attack the Bandaranaike International Airport. In contrast, a wave of suicide attacks was launched in Jaffna against the army to regain the territory that was under the control of the LTTE. These factors show that the LTTE not only decide whether to launch a suicide attack or not, but also how many suicide attackers are needed to deploy such an attack.

In the second category, suicide attacks were carried out based on the self-starter phenomenon. In this segment, suicide attacks were executed based on the autonomous decision taken by small cell members. Data relating to suicide attacks that had been carried out in Sri Lanka in 2019 has also been taken into consideration.

Frequency of Suicide Attacks

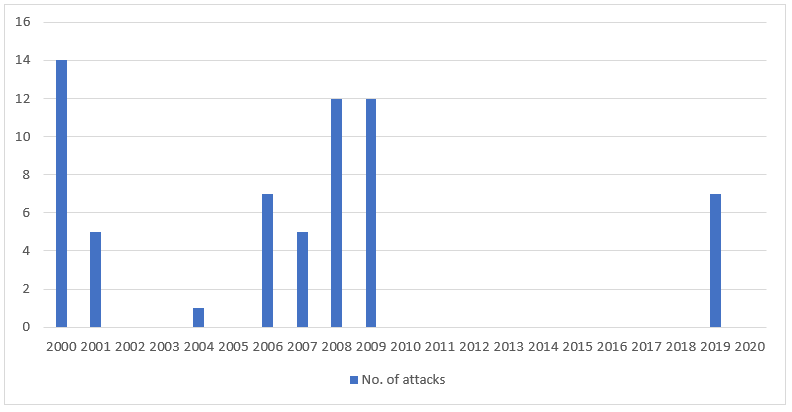

Sri Lanka had three decades of war with the LTTE, and the LTTE was militarily defeated in 2009. Between 2000 and 2009, it was observed that the LTTE had deployed suicide attacks as their weapons of choice. There was no suicide attack reported in 2002, 2003 and 2005. This may be as a result of the ceasefire agreement. According to the data, in 2003, three LTTE carders blew themselves up while the Sri Lanka Navy intercepted, but this incident was not recorded as a suicide bombing. After 2009, there were no suicide attacks reported that claimed to be done by the LTTE. Further, in 2019, seven suicide attacks were reported. These attacks were done by a small cell that claimed to embrace ISIS ideology. Graph 1 depicts suicide attacks that have been carried out from 2000 to 2020.

Sri Lanka had three decades of war with the LTTE, and the LTTE was militarily defeated in 2009. Between 2000 and 2009, it was observed that the LTTE had deployed suicide attacks as their weapons of choice.

Number of Suicide Attacks (2000 – 2020); Source: Global Terrorism Database

The above graph shows that suicide attacks have not been limited to one segment of terrorism, as it has been used by both terrorist organisations and small cells in Sri Lanka. Let us now move on to understand what the targets are that the militants have taken as a suicide mission.

Target

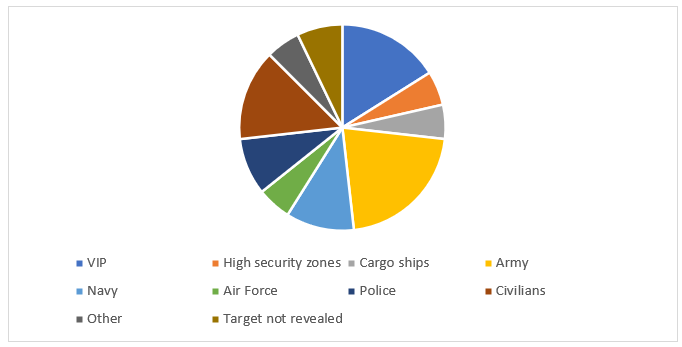

In a military operation, the weapons of choice become vital in accomplishing a target. It is necessary to understand why militants are tempted to deploy suicide attacks in taking specific targets and the possibility of reaching the said targets with other weapons. When analysing the targets taken as suicide attacks, it was observed that mainly targets are concentrated on military forces, namely the Sri Lanka Army, Sri Lanka Navy and Sri Lanka Air Force and that amounts to 33 per cent of all suicide attacks. Suicide attacks on the Sri Lanka Army intensified in 2009 as the Sri Lanka Army advanced troops in the LTTE-controlled area and regained control of the territory for the Sri Lanka government.

Police officers were subjected to suicide bombs when they apprehended suspects with suspicious behaviours and tried to question them. With the said findings, it can be inferred that the planned target was different, although the militant exploded near a police officer or within the premises of a police station. According to the available data, only 8 per cent of suicide explosions had occurred under this category. The other targets taken by suicide attacks are very important persons (VIPs) that represent the category of commanders of the tri forces and ministers, apart from civilians and cargo ships that transported food and other supplies to the conflict areas. As mentioned above and more fully depicted in graph 2, the LTTE, as a terrorist organisation, had deployed suicide attacks on various targets ranging from soft targets as civilians, to hard targets as military commanders.

Targets taken by Suicide Attackers; Source: Global Terrorism Database

The data above excludes the suicide terrorist attacks in 2019. The multiple suicide attacks that occurred in 2019 were aimed at civilians in three luxury hotels, namely Cinnamon Grand Colombo, Kingsbury Hotel and Shangri-La Hotel and churches, namely Shrine of St. Anthony Church, St. Sebastian’s Church and Zion Church. Later on, the same day, members of the same small cell carried out suicide attacks in another hotel named Tropical Inn and within a housing complex where some of the suicide members lived. With this data, it is explicit that the small cells go for suicide attacks on soft targets such as unarmed civilians.

Modus Operandi

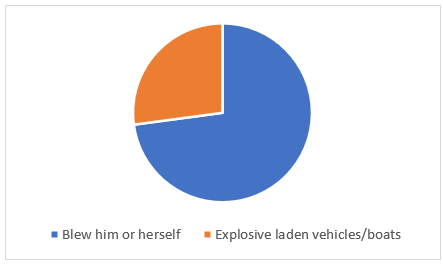

When analysing the modus operandi of suicide bombing, it was observed that most of the attacks were carried out by blowing up the person. For this purpose, the suicide bomber wrapped him/herself with explosives, and later, it was advanced to wearing a suicide vest. If a suicide vest is worn, it may be difficult to be seen by the public or the law enforcement authorities, which enables the militant to reach the target. Another point that can be drawn from wearing a suicide vest is that the military group or the terrorist organisation to which the militants were attached has the technological know-how to design a suicide vest to be operated by the same person who is wearing the vest. The same technology was not available to small cells and lone actors, and therefore, they deployed suicide attacks by carrying backpacks or rucksacks.

Further, it was observed that the suicide attacks were not limited to blowing themselves up, as they included blowing up boats and other vehicles laden with explosives. When militants target naval boats and cargo ships, it was observed that suicide missions were carried out by blowing up boats and cargo ships with themselves. According to the records, these attacks were carried out by the Black Sea Tigers, who seem to specialise in committing suicide terrorism at sea.

Mode of Operation; Source: Global Terrorism Database

Gender

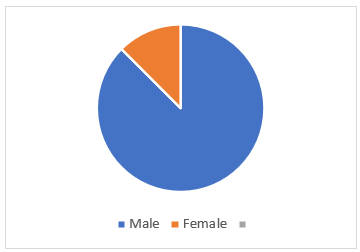

As per the available statistics, both males and females have deployed suicide attacks, but the number of attacks conducted by male suicide bombers is higher. When compiling data under the category of gender, it was observed that gender was not recorded, subject to the fact that if a female did the attack, it was recorded as a female suicide attacker. With this data, it can be concluded that gender has not become a barrier to deploying suicide attacks.

Gender of Suicide Bombers; Source: Global Terrorism Database

Conclusion

This paper has argued that when analysing the research on suicide bombing so far, it has focused on identifying the causes of why a person becomes a suicide bomber and not discussed whether suicide bombing can be taken as a weapon of choice. Therefore, there is a research gap, and this paper aims to fill the said research gap. The findings of this research show that suicide bombing can be used as a weapon of choice, as it is cost-effective and fulfils the objectives of the concerned parties. These concerned parties can vary from terrorist organisations, small cells, to lone attackers. How the concerned parties decide what is the right time to beat the drum or execute the suicide bombing will depend on rational thinking, and this may be subject to bounded rationality. One such method to mitigate the risk of suicide terrorism is to raise the cost of committing a crime by increasing situational crime prevention methods. The findings suggest that, in general, it is needed to strengthen situational crime prevention methods to avoid reaching hard targets such as military camps, advancing troops and VIPs. It has also required focusing on strengthening the security of soft targets, mainly mass gatherings of unarmed civilians, to avoid terrorists targeting such targets. On the other hand, suicide terrorism does not correlate with factors such as poverty and level of education, the methods of spreading the ideology and radicalisation. With the findings of this research, it was revealed that the objective of committing suicide terrorism is multi-faceted.

Noragal Dasni Lakmalee Hemchandra; Attorney-at-Law, LLB, and a Master’s in Economics and Public Policy from the University of Queensland, Australia. Her research interests include money laundering and terrorist financing. Previous works by her include an article on FATF standards, The Financing of Terrorism and the Characteristics of Terrorist Groups, The International Standards on Countering the Financing of Terrorism, What We Know About Self-Financed Terrorism, Implementing Anti-Money Laundering Laws: Challenges for Law Enforcement Authorities, National Risk Assessment on Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing: Lessons Learned, How the Promoters of Pyramid Schemes misled the Public and Does a Suspicious Transaction Report Fulfil the Financial Action Task Force’s Intention. The views in this article are the author’s own and do not represent the views of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka.

[1] Yoram Schweitzer, “Suicide Terrorism: Development and Main Characteristics,” Policy Institute for Counter-Terrorism (2001).

[2]Michael C. Horowitz, “The Rise and Spread of Suicide Bombing,” Annual Review of Political Science 18 (2015): 69-84.

[3] Ehud Sprinzak, “Rational fanatics,” Foreign Policy Sep/Oct 120 (2000): 66-73.

[4] Veronica Ward, “What Do We Know about Suicide Bombing?,” Politics and the Life Science 37, no.1 (2018): 88-112.

[5] Jean-Paul Azam, “Why Suicide-terrorists Get Educated, and What To Do About It?” Public Choice 153 (2012): 357-373.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ehud Sprinzak, “Rational fanatics,” Foreign Policy Sep/Oct 120 (2000): 66-73.

[8] Idem.

[9] Nasra Hassan, “Letter from Gaza: An arsenal of believers talking to the human bombs,” The New Yorker, November 19, 2001.

[10] Jean-Paul Azam, “Why Suicide-terrorists Get Educated, and What To Do About It?” Public Choice 153 (2012): 357-373.

[11] Ehud Sprinzak, “Rational fanatics,” Foreign Policy Sep/Oct 120 (2000): 66-73.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Jean-Paul Azam, “Why Suicide-terrorists Get Educated, and What To Do About It?” Public Choice 153 (2012): 357-373.

[14] Aidan Kirby, “The London Bombers as ‘self-starters’: A Case Study in Indigenous Radicalization and the Emergence of Autonomous Cliques,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 30 (2007): 415-428.

[15] Idem.

[16] Stephen Hopgood, Tamil Tigers 1987-2002 in Making Sense of Suicide Missions (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 43-76.

[17] Aidan Kirby, “The London Bombers as ‘self-starters’: A Case Study in Indigenous Radicalization and the Emergence of Autonomous Cliques,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 30 (2007): 415-428.

[18] Michael Levi and Melvin Soudijn, “Understanding the Laundering of Organized Crime Money,” Crime and Justice 49, no.1 (2020): 579-631.

[19] Derek B. Cornish and Ronald V. Clarke, The Reasoning Criminal: Rational Choice Perspectives on Offending (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1986).

[20] Financial Action Task Force, “Emerging Terrorist Financing Risks,” 2015, http://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/methodsandtrends/documents/emerging-terrorist-financing-risks.html on 10/3/2021.

[21] Featured Commission Publications, The 9/11 Commission Report: Final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (9/11 Report), https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/GPO-911REPORT.

[22] Gary Becker, “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach,” The Journal of Political Economy 76, no. 2 (1968): 169-217.

[23] Raymond Paternoster, Chae M Jaynes and Theodore Wilson, “Rational Choice Theory and Interest in the Fortune of Other,” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 54, no. 6 (2017): 847-868.

[24] Idem.

[25] Idem.

[26] Krisztina Kis-Katos, Helge Liebert and Gunther G. Schulze, “On the Heterogeneity of Terror,” European Economic Review 68 (2014): 116-136.

[27] Eric van Um, “Discussing Concepts of Terrorist Rationality: Implications for Counterterrorism Policy,” Defence and Peace Economics 22, no. 2 (2011): 161-179.

[28] Olive Emil Wetter and Valentino Wuthrich, “What is dear to you?” Survey of Beliefs Regarding Protection of Critical Infrastructure Against Terrorism,” Defense & Security Analysis 31, no. 3 (2015): 185-198.

[29] Todd Sandler and Walter Enders, “An Economic Perspective on Transnational Terrorism,” European Journal of Political Economy 20, no. 2 (2004): 301-316.

[30] Simon Perry and Badi Hasisi, “Rational Choice Rewards and the Jihadist Suicide Bomber,” Terrorism and Political Violence 27, no. 1 (2015): 53-80; Martin Innes and Michael Levi, “Making and Managing Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism,” in The Oxford Handbook of Criminology, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017): 455-477.

[31] BBC News, “Sri Lanka Attacks: What We Know About the Easter Bombings,” April 28, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-48010697.

[32] Idem.

[33] Gary Becker, “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach,” The Journal of Political Economy 76, no. 2 (1968): 169-217.

[34] Idem.

[35] Derek B. Cornish and Ronald V. Clarke, The Reasoning Criminal: Rational Choice Perspectives on Offending (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1986).

[36] Daniel Kahneman, “Maps of Bounded Rationality: Psychology for Behavioural Economics,” The American Economic Review 93, no. 5 (2003): 1449 -1475.

[37] Jean-Louis van Gelder and Reinout de Vries, “Traits and States: Integrating Personality and Affect into a Model of Criminal Decision Making,” Criminology 50, no. 3 (2012): 637-672; Jean-Louis van Gelder and Reinout de Vries, “Rational Misbehavior? Evaluating an Integrated Dual-Process Model of Criminal Decision Making,” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 30, no. 1 (2014): 1-27.

[38] Idem.

[39] Greg Pogarsky, Sean Patrick Roche and Justin Pickett, “Offender Decision Making in Criminology: Contributions from Behavioral Economics,” Annual Review of Criminology 1 (2017):379-400.

[40] Shoshana Shiloh, Efrat Salton and Dana Sharabi, “Individual Differences in Rational and Intuitive Thinking Styles as Predictors of Heuristic Responses and Framing Effects,” Personality and Individual Differences 32, no. 3 (2002): 415-429.

[41] Eric van Um, “Discussing Concepts of Terrorist Rationality: Implications for Counterterrorism Policy,” Defence and Peace Economics 22, no. 2 (2011): 161-179.

[42] UN Peacemaker, “Agreement on a Ceasefire Between the Government of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam,” February 22, 2022, https://peacemaker.un.org/sites/default/files/document/files/2024/05/lk020222ceasefireagreementgovernment-liberationtigerstamileelam.pdf; Reliefweb, “Sri Lanka: Government Abolishes the Ceasefire Agreement from 16 January 2008,” January 04, 2008, https://reliefweb.int/report/sri-lanka/sri-lanka-government-abolishes-cease-fire-agreement-16-january-2008.