Abstract: The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has prioritised identifying suspicious transactions carried out through the financial sector. The countries’ compliance with this recommendation is evaluated through mutual evaluation. This study sets out to understand what would be the objective of promulgating a recommendation on reporting suspicious transactions to the centralised authority of collecting suspicious transactions or, in other words, the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) and whether the FATF has achieved the said objective. Although the FATF’s scope covers money laundering, and the financing of terrorism and proliferation, the scope of this research was limited to terrorism financing and the reported suspicious transactions. The findings of this research will provide insight into the fact that the objective of the FATF has to be comprehensively delivered to the bottom line of the reporting entities without leaving any grey area.

Problem statement: What would be the objective of the Financial Action Task Force introducing the recommendation on filing a suspicious transaction?

So what?: Reporting suspicious transactions to the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) is one of the main sources of obtaining information regarding money laundering, and the financing of terrorism and proliferation. If this source of receiving information does not effectively operate, it may harm the holistic framework of anti-money laundering, countering the financing of terrorism and proliferation. Therefore, understanding what has been covered and not covered under the recommendation on suspicious transactions will enable policymakers to address the policy gaps in the said recommendation.

Source: shutterstock.com/NicoElNino

FATF Obligation on Reporting of STRs

FATF is the international policy setter on anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism and proliferation. It has stipulated in its recommendation 20 that “if a financial institution suspects or has reasonable grounds to suspect that funds are the proceeds of a criminal activity or are related to terrorist financing, it should be required, by law, to report its suspicions to the Financial Intelligence Unit promptly.”[1] The interpretative note to recommendation 20 broadens the scope of reportable transactions to include attempted transactions. In general, suspicious transactions cover criminal acts that constitute a predicate offence for money laundering and terrorist financing. The FATF further elaborates that terrorist financing includes financing terrorist acts and also terrorist organisations. Although the FATF recommended reporting suspicious transactions, it was not clear what it was required to uncover under ‘suspicious’ and precisely how the reporting institutions needed to adhere to this recommendation.

If a financial institution has reasonable grounds to suspect that funds are the proceeds of a criminal activity, it should be required to report its suspicions to the Financial Intelligence Unit promptly.

The FATF requires countries to make an obligation on institutions that are covered under the FATF to report suspicious transactions in accordance with recommendation 20. To comply with the said recommendation, first, it needs to clarify what is meant by terrorism or terrorism financing. It was said that one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.[2] There is no coherent definition given for terrorism or terrorism financing. Still, for the purpose of this research, the definition given for terrorism financing by Sri Lankan law has been followed. Accordingly, Section 3 of the Convention on the Suppression of Terrorist Financing Act, No. 25 of 2005, as amended, defines the offence of terrorism financing as follows:“ Any person who, by any means directly or indirectly, unlawfully and willfully provides or collects funds or property with the intention that such funds or property should be used or having reason to believe that they are likely to be used, in full or in part, to commit

- “An act which constitutes an offence within the scope of, or within the definition of any one of the Treaties specified in Schedule 1 hereto;

- Any other act, intended to cause death or serious bodily injury, to civilians or to any other person not taking an active part in the hostilities, in a situation of armed conflict, or otherwise and the purpose of such act, by its nature or context is to intimidate a population or to compel a government or an international organisation, to do or to abstain from doing any act; or

- Any terrorist act, shall be guilty of the offence of financing of a terrorist act, a terrorist or terrorists or a terrorist organization…”[3]

The absence of a universally accepted definition of terrorism financing presents significant challenges for collecting data. The lack of a coherent definition of terrorism and terrorism financing is a challenge for collecting data. When there is no cohesive definition of terrorism or terrorism financing, what is covered under one country may differ from another. A similar approach can be reflected in defining the offences of money laundering and the financing of the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. Further, a country’s tolerance level also needs to be considered when identifying terrorist activities. On the other hand, over the years, the status of a person may also be changed. For example, a patriotic can be transformed into a terrorist and vice versa. While accepting that countries have the sovereignty to draft the national laws and provide definitions, it also needs to be considered that countries need to adhere to international conventions to be part of global trade and other economic activities. Therefore, the definition given in national laws needs to comply with international recommendations and conventions when drafting legislation relating to terrorism financing. If so, the data collection challenge can be addressed somewhat. The same argument stands valid for defining money laundering and the financing of proliferation that were covered under FATF’s mandate.

The absence of a universally accepted definition of terrorism financing presents significant challenges for collecting data.

No specific definition of an STR has been given. In general, a report that is submitted to the FIU containing information relating to suspicious activity or transactions is referred to as a ‘suspicious transaction report’. Gowhor proposes that a STR is a financial intelligence tool.[4] Before proceeding further, the difference between information and intelligence needs to be clarified. In general, ‘information’ refers to facts, whereas ‘intelligence’ refers to an external process that uses data from all accessible sources to lower a decisionmaker’s degree of uncertainty.[5] Although the FATF does not specifically mention whether recommendation 20 refers to reporting facts about a suspicious transaction or financial intelligence, from the literal meaning of the words, it is deemed that the FATF would intend to take immediate action on the suspicious transaction irrespective of the nature of reporting: information or intelligence.

This raises the question of whether a mere report of facts submitted by a reporting entity can prompt the FIU to take regulatory action, such as issuing a freezing order or seizure. In the absence of specific guidance issued by the FATF at the discretion of the FIU, the FIU may take regulatory action on the suspicious transaction or collect more information on the suspicious transaction. If the FIU collects further details, the FIU can make an informed decision on whether to proceed with regulatory action or not. To take regulatory action at any stage, what needs to be contained in an STR matters: information or intelligence. On the same note, when implementing a recommendation on reporting suspicious transactions, the FATF needs to be aware that transforming information into intelligence is time-consuming. This is because, to transform information into intelligence, the FIU needs to collect information from open sources as well as the information maintained by government and private institutions that have limited access to the public and authorities. Thereafter, the information collected from various sources needs to be analysed to see the holistic picture of the suspicious transactions. The collection of information includes the volume and value of transactions, the related parties, mule accounts (if any), and the beneficiary accounts. Taking action on a suspicious transaction should not be limited to freezing a particular account or transaction. It has to be extended to freezing a specific account or transaction and all the other related accounts and transactions. To elaborate further, if the wrongdoer had transferred money into another account of his own or to a third party, the cause of action has to cover not only the initial bank account but also the other accounts maintained by the wrongdoer that may be in different banks and with third party account holders.

If the wrongdoer had transferred money into another account of his own or to a third party, the cause of action has to cover the initial bank account and also the other accounts maintained by the wrongdoer.

This leads to the question of what information is needed to take regulatory action or decide whether such a transaction or an attempted transaction is suspicious. Gowhor proposes that the STR serves as a financial intelligence tool, and the content serves three key purposes.[6] Firstly, a STR provides a source of financial intelligence that can be used to identify potential criminal activities. Secondly, the financial intelligence revealed in an STR can be used for investigative purposes. Thirdly, a STR can be used to deter criminals from entering the global financial system. Gowhor states that the striking features of an STR are that it has the capacity to produce actionable intelligence and that, once disseminated to law enforcement authorities, actions can be taken based on financial intelligence.[7] As illustrated by Gowhor, reporting information relating to suspicious and attempted transactions is not limited to freezing accounts but can be further used to facilitate investigations.[8]

The Global Terrorism Index has categorised the risk of terrorism under three categories: (1) the risk of terrorism occurring as a result of an ongoing larger conflict, (2) the risk of terrorism when there is no conflict, and (3) the risk of unexpected and severe attacks on individuals and businesses that are referred to as ‘black swan’ attacks.[9] It needs to identify whether the STR can address all the categories mentioned in the Global Terrorism Index. In the first scenario, when there is an ongoing conflict, law enforcement authorities may have an idea about the trends and patterns of terrorism financing that provide financial resources to the conflict. Once the indicators are given, the officers overseeing suspicious transactions may be able to detect and report STRs. The effectiveness of the STR may be attributed to the indicators that were provided by the law enforcement authorities to a certain extent. In the second scenario, when there is no conflict, financial institutions need to search for unusual and suspicious transactions through millions of financial transactions to identify the possibility of terror financing. Furthermore, financial institutions need to search for the names in watch lists. Thirdly, black swan attacks refer to unexpected attacks such as cyber-attacks. The likelihood of identifying such attacks through STRs may be limited. In light of the above context, the applicability of STRs varies according to the risk of terrorism.

When instructions were given to the financial institutions followed by on-site supervision, it was observed that the over-role compliance with the anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism framework had improved. The outcome of the on-site inspection done by the Italian Financial Intelligence Unit denotes that the on-site examination increased the number of filings STRs and the bank staff skills.[10] On the same note, filing an STR depends on the staff member’s skills and to enhance the said skills, training should be given beyond learning on the job. Vineer proposes that bank staff need to be given training that the specialists deliver.[11] Although the findings of the Vineer were focused on questioning the customers, the same principle can be applied to detect STRs. The findings of the above sections indicate that financial institutions are obliged to report suspicious transactions: however, it was not clear whether more reporting will be sufficient to comply with FATF recommendations.

When instructions were given to the financial institutions followed by on-site supervision, the over-role compliance with the anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism framework had improved.

Present Framework on Reporting STRs

Without FATF providing a format to report suspicious transactions, the FIUs may instruct reporting institutions to submit information in a particular format. For example, FIU-Sri Lanka has provided a format to follow when reporting a suspicious transaction.[12] The FIU-Sri Lanka, by their regulation made under the provisions of the Financial Transactions Reporting Act, No. 06 of 2006, has given specific instructions to the reporting entities in 2017.[13] Accordingly, banks and finance companies, stockbrokers, insurers and authorised money-changing companies were given schedules from I to IV, respectively. If any institution does not fall under the above categories, such institution may report suspicious transactions as per schedule V. When further analysing schedules from I to IV, it was observed that each schedule had been divided into parts from A to F. Through these parts, information pertaining to the customer and details of the suspicious transaction have been collected, apart from the administrative information such as details of the report, details of reporting officer and compliance officer and some information for office use.[14] There is a difference in the content referred to in Part D as it specifically provides instructions on forming a suspicion relating to the nature of the business. With this information, it was observed that FIU-Sri Lanka has given a tailormade form to report suspicious transactions without relying on one form that fits all.

It is also needed to understand whether providing an STR format will fulfil the objectives of the FATF recommendations. This includes who should file the STR and what the content of the STR needs to be. When unveiling who should file an STR, it is observed that STRs can be generated at the ground level, as the officers facing the public will have the opportunity to understand that the transactions do not tally with the economic profile of the customer. Identifying suspicious transactions is closely associated with personal judgements or an objective view of the circumstances of the staff officer, and therefore, it opens a pace to being biased. The next point, based on the content of the STR, can be divided into two parts: defensive reporting and excessive reporting. Defensive reporting refers to filing STRs only to avoid regulatory actions and without paying much attention to the facts revealed, which is insufficient to initiate an investigation.[15] Excessive reporting is commonly referred to as ‘crying wolf’, where reporting institutions report suspicious transactions to achieve the target. In this situation, reporting institutions may report fewer suspicious transactions.[16] In both defensive and excessive reporting, sufficient information will not be provided to lead to an investigation. On this premise, introducing an STR format will streamline filing an STR, but there are still questions about whether the required information can be obtained through the said format.

Excessive reporting is commonly referred to as ‘crying wolf’, where reporting institutions report suspicious transactions to achieve the target.

Providing training for the staff officers of the reporting entities can overcome the filing of an STR without sufficient grounds for suspicion. Overall knowledge in the areas of money laundering and terrorist financing is proposed. While doing so, specific investigative training rather than general training on the subject matter must be given to the staff officers of the reporting entities.[17]

Methodology

In general, an STR can be raised for criminal activities that fall under the category of money laundering and terrorist financing. Out of the above categories, to fulfil the objectives of this research, several STRs that have been reported to the FIU in relation to terrorism financing have been collected from the FIU Annual Reports from 2006 to 2022.[18] STRs on money laundering have also been extracted to provide an in-depth analysis. The Sri Lankan FIU was established in 2006, and the number of STRs reported since then has been considered.[19] The data on terrorism financing was compared with the data on terrorist activities reported for the same period by the Global Terrorism Database.[20] The Global Terrorism Database is an open-source database that records terrorist events from 1970 to 2020. Out of the said database, the terrorist attacks that occurred from 2006 to 2020 have been extracted to analyse this research. The data gathered through the FIU annual reports and Global Terrorism Database has been used to assess the validity of the hypothesis of whether the number of STRs reported by reporting institutions correlated with the terrorist incidents.

Data Analysis

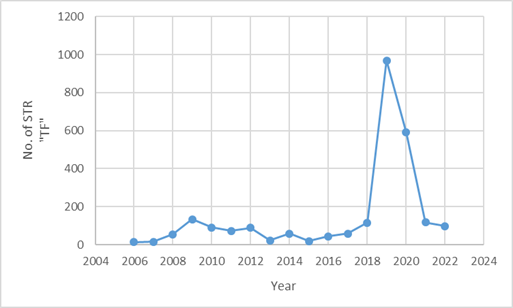

In the data analysis, it was considered whether introducing an STR would impact the number of suspicious transactions reported on terrorism financing by reporting entities. For this purpose, the number of STRs filed for the period from 2006 to 2022 has been graphed as below:

Number of suspicious transaction reports; Source: Financial Intelligence Unit of Sri Lanka Annual Reports (2006 -2022).

The number of STRs filed has steeply increased from 2018 to 2019. From the data, it was unclear whether the increase was attributed to the introduction of suspicious transaction formats in 2017.[21] Comparatively, there was an increase in 2009, but compared with 2019, the increase in 2009 was negligible. Sri Lanka faced decades of conflict with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), and the LTTE was militarily defeated in 2009. Still, the number of STRs submitted for the period of 2006 to 2009 remains low despite the ongoing conflict with the LTTE at that time.[22] Through the recorded number of STRs, it was not explanatory why the number remains low;[23] it may be due to other factors, such as the offence of terrorism being subjected to different national laws, regulations, and rules.

For example, when Sri Lanka was on a war footing, emergency regulations were made under Public Security Ordinance No. 25 of 1947.[24] Emergency regulation has the authority to prevail over the other laws as and when necessary and empower authorities or persons designated to confiscate property, including the money lying credited to the bank accounts, without being referred to the other authorities to take regulatory actions. The funds lying credited to the Tamil Rehabilitation Organisation amounting to LKR 71 million and 18 million, which is equivalent to USD 242,341 and USD 61,438.7 (USD 1 = LKR 289.56 as of 25.11.2024, Oanda Currency Converter),[25] were forfeited to the state in July 2008 and January 2009, respectively, with the operation of the provisions of the regulations made under the Public Security Ordinance without operating the provisions on the Conventions on the Suppression of Terrorism Financing Act, No. 25 0f 2005.[26] As the FIU data related to the actions taken by the FIU, the statistics may not reflect the comprehensive data concerning terrorism financing.

Again, it was doubtful whether the rise of STRs recorded in 2019 was due to the multiple terrorist attacks in the same year. As stated by Gowhor, if the STRs on terrorist financing were reported before the multiple terrorist attacks, such information could be treated as actionable information.[27] If reported after the attack, the information revealed in the STRs can be used for investigations. To clear the doubt on the cause of the increase in STRs, reports filed for the suspicion of money laundering have been considered.

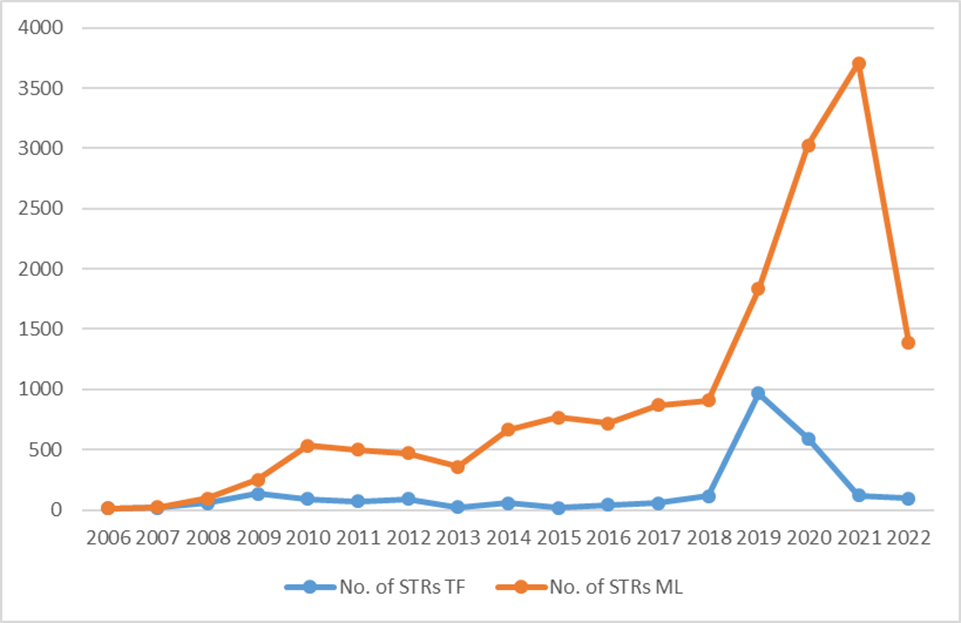

Reported STRs on terrorism financing and money laundering; Source: Financial Intelligence Unit of Sri Lanka Annual Reports (2006 -2022).

It was observed that after the FIU introduced specific formats in 2017, there was an increase in the number of STRs on money laundering and terrorist financing filed by the reporting institutions. Through these data, it was not clear whether the increase in the number of STRs on terrorism financing was attributed to providing a specific format because Sri Lanka faced the deadliest terrorist attacks in 2019, which killed 266 people and injured at least 500.[28] There was an increase in the number of STRs on money laundering from 2017 onwards. When comparing the number of STRs on money laundering reported before 2017 and after 2017, it was observed that the numbers are high on money laundering after 2017. On this basis, it can be assumed that providing a specific institutional format will enable the reporting institutions to trace more suspicious activities concerning money laundering and terrorist financing.

Firstly, the main element of reporting an STR is that the money must enter the formal financial sector. The FATF recommendations provide indications or red flags to identify suspicious transactions in the formal financial sector, and they do not penetrate the underground economy to trace suspicious transactions. To explain further, the financial transactions done in the underground economy will not be captured through the FATF recommendations. To make FATF recommendations effective, the FATF needs to pay attention to shrinking the underground economy. Secondly, the FATF recommendations on terrorism financing were implemented as a result of the attacks in the USA, which are known as the 9/11 attacks.[29] The focus of the FATF was to identify large and complex transactions financed through the international financial system.[30] To determine the effectiveness of raising STRs on small cells, as a pre-requisite, it needs to identify whether the small cells used the formal financial sector.

The FATF recommendations on terrorism financing were implemented as a result of the attacks in the USA, which are known as the 9/11 attacks.

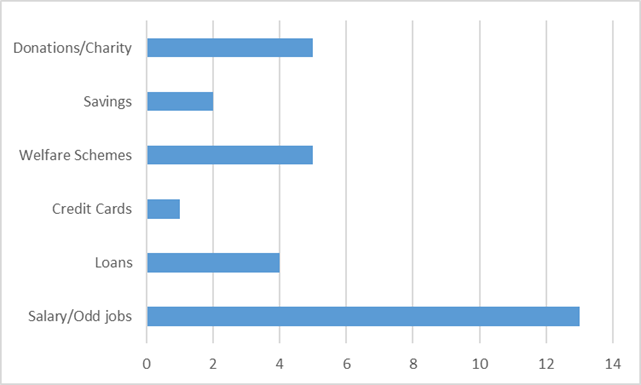

For this purpose, data was collected from the research done by Oftedal on 25 small cells operated in Europe.[31] According to the findings of the Oftedal, these small cells used several methods to finance their terrorist activities. However, it has to be noted that since there is no separation between the financing of terrorist activities and day-to-day activities, the money may be intermingled with terrorism financing and day-to-day activities. Further, a small cell may receive money from several sources, such as the London underground bombing. The small cell that executed the London underground bombing received funds from salary or odd jobs, bank loans and personal loans, and credit card debts.[32] A few members were supported by their families during day-to-day activities. The common methods of the source of funds for small cells are (I) salary/odd jobs, (II) bank loans and personal loans, (III) credit card debts, (IV) supported by family, (V) supported by a terrorist organisation, (VI) welfare schemes, (VII) savings, (VIII) donations and charity, (IX) petty crimes, (X) serious criminal offences such as drug trafficking, (XI) sale of a property and (XII) other.[33]

Of these twelve methods, it was reasonable to assume that bank loans and personal loans, credit card debts, and welfare schemes may have proceeded through the banks subject to the FATF recommendations. Further, it can also be assumed that donations and charity, savings and salary and payments for odd jobs may also be processed through the banking sector if no payments were given in cash. The data below shows that small cells do use the facilities provided by the banking sector.

Sources of income by small cells; Source: Oftedal, 2015.

Thirdly, suppose the money was entered into the banking sector. In that case, it needs to be investigated whether the banking sector is capable enough to trace the suspicious transactions that led to the identification of the perpetrators. To identify the capability of the banking sector with respect to the financing patterns, the data presented in the annual reports published by the FIU were compiled. The statistics extracted from the Annual Reports of the Financial Intelligence Unit of Sri Lanka were compiled according to the time period below:[34]

- 2006 – 2009

- 2010 -2017

- 2018 – 2022

The data was categorised from 2006 to 2009 based on the fact that the Sri Lankan military defeated the war with the LTTE in 2009. After that, 2017 was taken as a benchmark because the STR format was introduced in 2017. Data relating to before and after implementing the STR format was compiled separately.

The period from 2006 to 2009 covers data on where the LTTE was operated. The LTTE is a territory-controlling terrorist group; hence, it can be assumed that the FATF recommendations were capable enough to capture suspicious transactions. Research identifies the methods of terrorist financing, particularly the LTTE and other similar organisations.[35] When there is an ongoing war, it can be assumed that the number of STRs reported should be high. However, the number of STRs reported remains comparatively low compared to the latter part of the graph. It was interesting to identify the causes that remain a smaller number of STRs. Since the annual reports were published in 2011, there is no reference to why the number of STRs remains low. It can be inferred that due to the operation of Emergency Regulations made under the provisions of the Public Security Ordinance, funds connected to terrorism financing may be subjected to Emergency Regulation, which deprives taking actions under the FATF recommendations.

Now, this research is being conducted to understand the STRs reported from 2010 to 2017. For the given period, the number of STRs reported remains low. According to the Annual Report in 2013, the number of STRs reported deceased since 2009; the number decreased with the end of internal conflicts. Further, the annual reports revealed a declining trend in reporting STRs based on non-profit organisations. The 2012 annual report revealed that the STRs were reported based on ‘large or unusual cash deposits or withdrawals not consistent with the known pattern of transactions without any economic rationale and irregular, unusual offshore activity.’[36]

STRs were reported based on ‘large or unusual cash deposits or withdrawals not consistent with the known pattern of transactions without any economic rationale and irregular, unusual offshore activity.’

Again, there was a steep increase from 2018 to 2022. This may be attributed to the Easter Sunday attacks, which occurred on 21.04.2019. Easter Sunday attacks were executed by a small group of people who claimed to have embraced the ideology of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). It was natural to raise the number of STR after the terrorist attack as the reporting entities report data relating to ISIS and the related party. This information revealed can be taken to carry out investigations, and, as mentioned by Gowhor, proving information through an STR covers one aspect of reporting the STR.[37] Similarly, it needs to be understood whether the reporting entities could detect suspicious transactions before the attack as a precautionary method. The explanations given in the annual reports from 2006 to 2022 show no reference to suspicious transactions detected in the new form of terrorism. The new form of terrorism derived money for their terrorist activities through bank loans, government benefit schemes and unemployment benefit schemes.[38]

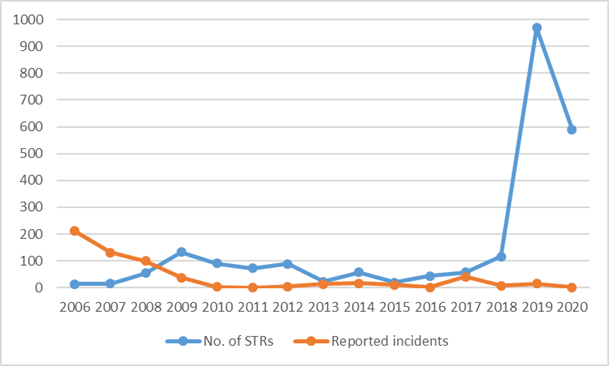

Finally, the question remains whether there is a correlation between the number of STRs reported on TF and the terrorist incidents that took place from 2006 to 2020. It has to be noted that the reported incidents that the Global Terrorism Database identifies as terrorist incidents do not correlate with the number of STRs reported on terrorism financing.

The number of STRs on TF and terrorist incidents; Source: Global Terrorism Database and Financial Intelligence Unit of Sri Lanka Annual Reports.

Conclusion

Implementing a recommendation on reporting suspicious transactions to the FIU as recommended by the FATF may not fulfil its objectives. The main reason is that the objective of implementing a recommendation on reporting suspicious transactions is not comprehensively conveyed to the reporting institutions. The data revealed that introducing specific formats based on the nature of the business has a positive impact on increasing the number of STRs filed by the reporting institutions. However, increasing the number of STRs and the quality of the content has no reference. To increase the number and the quality of the content of the STR, more information must be provided to the reporting entities. Since the national laws are based on international standards promulgated by the FATF, it is recommended that the requirement of filing an STR has to be delivered to the reporting institutions comprehensively.

Noragal Dasni Lakmalee Hemachandra holds the following titles: Attorney-at-Law, LLB, and a Master’s in Economics and Public Policy from the University of Queensland, Australia. Her research interests are money laundering and terror finance. Previous works by her include an article on FATF standards, The Financing of Terrorism and the Characteristics of Terrorist Groups, The International Standards on Countering the Financing of Terrorism, What We Know About Self-Financed Terrorism, Implementing Anti-Money Laundering Laws: Challenges for Law Enforcement Authorities, National Risk Assessment on Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing: Lessons Learned, and How the Promoters of Pyramid Schemes misled the Public. The views in this article are the author’s own and do not represent the views of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka.

[1] “FATF Recommendations,” Financial Action Task Force, last updated November 2023, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/content/dam/fatf-gafi/recommendations/FATF%20Recommendations%202012.pdf.coredownload.inline.pdf.

[2] Harmen van der Wilt and Christopher Paulussen, “The role of international criminal law in responding to the crime-terror nexus,” European Journal of Criminology 16, no.3 (2019): 315-331, https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370819828934.

[3] “Convention on the Suppression of Terrorism Financing Act, No. 25 of 2005,” November 24, 2024, https://fiusrilanka.gov.lk/acts_regulations.html.

[4] Hussain Syed Gowhor, “Effectiveness criteria of suspicious transaction reporting for early detection of terrorist financing activities,” Journal of Financial Crime 2023, http://doi.org/ 10.1108/JFC-10-2023-0254.

[5] Kristan J. Wheaton and Michael T. Beerbower, “Towards a new definition of intelligence,” accessed October 05, 2024, https://law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/wheaton_beerbower_319.pdf.

[6] Hussain Syed Gowhor, “Effectiveness criteria of suspicious transaction reporting for early detection of terrorist financing activities,” Journal of Financial Crime (2023), http://doi.org/10.1108/JFC-10-2023-0254.

[7] Idem.

[8] Idem.

[9] “The Global Terrorism Index 2014,” Institute for Economics & Peace, accessed November 01, 2024, https://www.visionofhumanity.org/maps/global-terrorism-index/#/.

[10] Mario Gara, Francesco Manaresi, Domenico Marchetti and Marco Marinucci, “Anti-money-laundering oversight and banks reporting of suspicious transactions: some empirical evidence,” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 40, no.2 (2024): 434-469.

[11] Annalise Vineer, “Perceptions of barriers to conducting effective AML investigations,” Policing 15, no.4 (2020): 2194-2209.

[12] “Suspicious Transactions (Format) Regulations of 2017,” accessed August 29, 2024, https://fiusrilanka.gov.lk/docs/Regulations/2015-56/2015-56(E).pdf.

[13] “Financial Transactions Reporting Act, No. 6 of 2006,” accessed September 07, 2024, https://fiusrilanka.gov.lk/docs/ACTs/FTRA/Financial_Transactions_Reporting_Act_2006-6_(English).pdf.

[14] Suspicious Transactions (Format) Regulations of 2017, accessed August 29, 2024, https://fiusrilanka.gov.lk/docs/Regulations/2015-56/2015-56(E).pdf.

[15] Annalise Vineer, “Perceptions of barriers to conducting effective AML investigations,” Policing 15, no.4 (2020): 2194-2209.

[16] Elod Takats, “A theory of “crying wolf”: The economics of money laundering enforcement,” The Journal of Law, Economics and organizations 27, no.1 (2011): 32-78.

[17] Laurence Webb, “A survey of money laundering reporting officers and their attitudes towards money laundering regulations,” Journal of Money Laundering Control 7, no. 4 (2004): 367-375.

[18] “Annual Reports,” Financial Intelligence Unit, accessed September 01, 2024, https://fiusrilanka.gov.lk/annual_reports.html.

[19] “Financial Intelligence Unit of Sri Lanka,” Financial Intelligence Unit, accessed August 23, 2024, https://fiusrilanka.gov.lk/.

[20] The Global Terrorism Index 2014,” Institute for Economics & Peace, accessed November 01, 2024, https://www.visionofhumanity.org/maps/global-terrorism-index/#/.

[21] Suspicious Transactions (Format) Regulations of 2017, accessed August 29, 2024, https://fiusrilanka.gov.lk/docs/Regulations/2015-56/2015-56(E).pdf.

[22] “Financial Intelligence Unit of Sri Lanka,” Financial Intelligence Unit, accessed August 23, 2024, https://fiusrilanka.gov.lk/.

[23] Idem.

[24] Public Security Ordinance, No. 25 of 1947, accessed August 06, 2024, https://www.srilankalaw.lk/p/968-public-security-ordinance.html.

[25] “Vulnerability of using charitable organization for terrorist financing,” Financial Intelligence Unit of Sri Lanka-Annual Report 2011, accessed August 01, 2024, https://fiusrilanka.gov.lk/docs/AR/FIU_AR_2011.pdf.

[26] “Convention on the Suppression of Terrorism Financing Act, No. 25 of 2005, November 24, 2024, https://fiusrilanka.gov.lk/acts_regulations.html.

[27] Hussain Syed Gowhor, “Effectiveness criteria of suspicious transaction reporting for early detection of terrorist financing activities,” Journal of Financial Crime (2023), http://doi.org/doi: 10.1108/JFC-10-2023-0254.

[28] “The Global Terrorism Index 2020,” Institute for Economics & Peace, accessed November 01, 2024, https://www.visionofhumanity.org/maps/global-terrorism-index/#/.

[29] “The 9/11 Commission Report: Final report of the National Commission on terrorist attacks upon the United States (9/11 Report),” Featured Commission Publications (2004), accessed July 31, 2024, https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/GPO-911REPORT.

[30] Stephen Reimer and Matthew Redhead, “Financial intelligence in the age of lone actor terrorism,” Project craft (2020), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e399e8c6e9872149fc4a041/t/5f68980428978b1bff33f264/1600690203310/CRAAFT_+RB3_Reimer+Redhead.pdf; Stephen Reimer and Matthew Redhead, “A new normal: countering the financing of self-activating terrorism in Europe,”(2021), https://rusi.org/publication/occasional-papers/new-normal-countering-financing-self-activating-terrorism-europe.

[31] Emilie Oftedal, “The financing of jihadi terrorist cells in Europe,” Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (2015),a ccessed August 05, 2024, https://ffi-publikasjoner.archive.knowledgearc.net/bitstream/handle/20.500.12242/1103/14-02234.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[32] Aidan Kirby, “The London bombers as “self-starters”: A case study in Indigenous radicalization and the emergence of autonomous cliques,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 30, no.5 (2007): 415-428.

[33] Emilie Oftedal, “The financing of jihadi terrorist cells in Europe,” Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (2015), accessed August 05, 2024, https://ffi-publikasjoner.archive.knowledgearc.net/bitstream/handle/20.500.12242/1103/14-02234.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[34] Idem.

[35] Ravinatha Aryasinha, “Terrorism, the LTTE and the conflict in Sri Lanka,” Conflict, Security & Development 1, no. 2 (2006): 25-50; Peter Chalk, “The Tigers abroad: How the LTTE diaspora supports the conflict in Sri Lanka,” Georgetown Journal of International Affairs 9, no.2(2008): 97-104; Anton Weenink, “Situational prevention of terrorism. Remarks from the field of counterterrorism in the Netherlands on Newman and Clarke’s policing terrorism,” Trends in Organized Crime 15 (2012): 164-179.

[36] “Financial Intelligence Unit of Sri Lanka- Annual Report 2012,” Financial Intelligence Unit, accessed October 02, 2024, https://fiusrilanka.gov.lk/docs/AR/FIU_AR_2012.pdf.

[37] Hussain Syed Gowhor, “Effectiveness criteria of suspicious transaction reporting for early detection of terrorist financing activities,” Journal of Financial Crime (2023), http://doi.org/ Doi: 10.1108/JFC-10-2023-0254.

[38] “Emerging terrorist financing risks,” Financial Action Task Force 2015, http://www.fatf-gafi.org/publications/methodsandtrends/documents/emerging-terrorist-financing-risks.html on 10/3/2021.