Abstract: As an output of strategic culture, a State Defence Strategy should set the direction of the defence policy and focus on defence system development and employment. As the main effort line to shape plans to be a reliable alliance member, the Slovenian Defence Strategy takes over the burden of collective defence (capabilities and operations). It fosters democracy, human rights, and civil and parliamentary military control. Strategic culture as a result of a “negotiated reality” built over time is the sum of values specifically for Slovenia’s culture, still partially based on the Second World War revolutionary character, comradeship, patterns of nonalignment foreign policy behaviour and ideologies of the one political party system. Emotional instead of rational responses to the legacy Total People’s Defence concept are presented at parliament and leading Slovenian newspapers.

Problem statement: How to exlain strategic incompetency by analysing strategic culture or strategic “personality”?

So what?: The Slovenian state should set the conditions for strategic cultural innovation, mindset change, and a new Way of War.

Source: shutterstock.com/irena iris szewczyk

Politics by Other Means

Policies are untested hypotheses that provide the overall direction and approach for achieving success while focusing on maintaining order. Strategic culture can be understood as a set of shared beliefs, assumptions, and modes of behaviour in war, derived from shared experiences and accepted narratives, that shape collective identity and determine ways of war,[1] for achieving political objectives.

One of the most cited political and military scholar’s war prophets, Carl von Clausewitz’s ideas, is that “war is the continuation of politics by other means”. If war belongs to politics, it will affect states involved in the Way of War they conduct and involved states’ war character. If the politics are megalomanias, like Slobodan Miloševič Yugoslavia, Vladimir Putin, Russia or Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel, the states conducting the way of wars might be the same.[2] Megalomanias and magnificent war characters suppose the absence of law and custom of war respect during warfighting. Political leadership intentions and biases define when and how a state’s military forces go to war and the type of war they intend to fight. The 20th anniversary of the Republic of Slovenia’s NATO membership is marked by the unsuccessful development of the Slovenian defence system, which should have resulted in a defence system and a Slovenian army capable of cooperating with allies in high-intensity wars. After 20 years of Slovenia’s membership in one of the most successful alliances in history, Slovenian defence ministers still repeatedly adhere to the concept of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia’s TPS&SSP concept. During two decades of unsuccessful development under governments from various political options, a substantial problem of no-solving ethics can be noted. The same result and consequences for the Slovenian Defence Strategy point to deeper causes of strategic incompetence, an absence of strategic thinking by Slovenian strategists, if there is any. Discovering these deeper causes will enable a broader discourse and the elimination of the trend where decision-makers in defence policy search for solutions without strategic thinking, relying on the legacy concept in the Slovenian case TPS&SSP concept, without awareness of the consequences for the state and citizens.

If the politics are megalomanias, like Slobodan Miloševič Yugoslavia, Vladimir Putin, Russia or Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel, the states conducting the way of wars might be the same.

Such research is vital because strategic culture can inform the personnel who define and control the implementation of policies on using armed forces along with ways of conducting warfare and behaviour in war. The ways of wars during the dissolution of the second Yugoslavia, marked by genocide, ethnic cleansing, and war crimes—in short, the absence of respect for all norms and agreements of warfare—must be appropriately addressed.

The Defence Strategy approved by the government in 2024 is analysed to fulfil its intent. Until 2020, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) staff assessment of the development of Slovenia’s capabilities, publicly announced in 2020, is used as a result or outcome of Defence Strategies.

In addition, the published articles and speeches, all from government-affiliated papers, and public statements from 2024 on two critical events, the 20th anniversary of Slovenia’s membership in NATO and the 75th anniversary of NATO, are included in the analysis, too.

Slovenian National Character, Strategic Culture and Way of War

Strategic culture as context relies on the view that strategic culture is, in many ways, unchanging, nation-specific, and should be studied through historical accounts. Suppose policymakers fail to craft a strategy and understand the war they are preparing for, as in the Slovenian case. Consequently, a defence strategy based on the TPD&SSP concept with roots in Slovenian strategic culture and the NATO strategy, which shapes a Defence Strategy based on collective defence with roots in current policy, is misaligned. The effect could be a failure in the overall war, likely defence against Russia or how armed forces are used, stabilising as now and likely manoeuvre one in the future. In contemporary wars, Russia and Israel plan manoeuvre wars with main objectives: first, to demilitarise and second, to destroy the opponent military with the end state annexing territories and fulfilling imperial or religious imperatives. Observation can be made that both wars ended in long attrition wars where the opponent will be, at best, degraded.

The type of war states wage is related to national character and strategic culture; consequently, no one is immune. As part of their national character, some nations understood war and related brutality as a tool to spread revolutionary ideology or religion, such as communism, Zionism, or several Balkan nationalisms. The linear causal relationship between strategic cultures – a type of war exists. Nations have distinct traditions, rituals, and customs passed down through generations. These may include festivals, food, art, music, and language, as well as how nations fight wars or the type of war that embodies the nation’s history and beliefs. Village burning and ethnic cleansing have, as the Carnegie Endowment pointed out, traditionally accompanied Balkan wars. As Hadžič rightly observed. It is impossible to overlook the similarities in the type of war and the way it was conducted between the dissolution of the Kingdom and Socialist Yugoslavia,[3] the occupation from 1941 to 1945, the immediate post-war events, the breakup of Socialist Yugoslavia, and the collapse of Milošević’s Yugoslavia only confirm similarities. Moreover, the post-war extrajudicial killings in 1945 of the Slovenian National Army, returned from Austrian Carinthia to Soviet Slovenia, are very similar to the massacres of the Muslim male population in Srebrenica in 1995.

The type of war states wage is related to national character and strategic culture; consequently, no one is immune.

Policies are guidelines to achieve specific goals and ensure consistent decision-making. Influences of ideology, communism or democracy, and religion on a state’s decisions influence policies today. In governmental and allied policy alignment, there is no gap between doctrine and Way of War and the concepts of manoeuvre or attrition warfare. Doctrine is the body of formalised principles and best practices that guide activities. Ways of using force are described in doctrine and are based on the type of war and type of operations, as well as basic abilities supported by capabilities. The doctrine gets its guidance from official governmental and NATO policy.

Strategic culture is stronger than ideology. The traumatic division within and among the nations did not bother in 1945, the Slovenians in particular and Yugoslavs in general communists; on the contrary, it became an additional generator of the renewal of “revolutionary energy”. The permanent revolution ended with a continuous (fifty-year) “struggle” against the same enemy. So, the last Yugoslav wars are just a continuation of the previous war.[4] The First and Second Balkan Wars, the First World War, national liberation wars, and wars for the borders of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the Second World War, a War for nation survival with embedded Civil war, and Wars for the dissolution of Second Yugoslavia are marked by genocide, ethnic cleansing, and War crimes on all involved sides. Strategic culture defines the way and type of war is conducted.

The traumatic division of the Slovenian nation is a consequence of World War II on Slovenian soil and the events during and after the war. The presence of “revolutionary energy” and the absence of catharsis cannot be overlooked today in Slovenian public and political discourse. The type of war and the approaches used in Croatia between Croats and Croatian Serbs, as well as between Serbs, Croats, and Bosnians in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and between Serbs and Albanians in Kosovo, are very similar to the conflicts during the Second World War.

The traumatic division of the Slovenian nation is a consequence of the Second World War on Slovenian soil and the events during and after the war.

The strategic culture’s resistance to changes is shown from the last Balkans wars. The war otherwise displayed new armies of new states of official and covert continuity of the Yugoslav People’s Army (YPA). The national militaries of the resulting states emerged from the war with a new image and ideology: all symbols, organisation, system and command language, models of completion, and logistic support were changed. With the abolition of the Second Yugoslavia, the new countries could not abolish the socio-historical heritage and environment, nor did they become immune to the “YPA syndrome”.[5]

The new armies emerged from the Balkan wars of the nineties with a new image, ideologies, symbols, organisation, system and language of command, completion models, and logistic support. The new army can be self-sufficient to the extent that countries have abolished the authoritarian regime of the former Yugoslavia. With the abolition of Yugoslavia, the new countries could not abolish the socio-historical succession of the YPA. The silence about the YPA links the new and old armies, as evidenced by the absence of sociological and military-political analyses.

The YPA was the last line of defence of the communist ideology; the new armies only replaced the communist ideology with a new nationalistic one. Party-political suitability is a criterion for selecting candidates; the criterion in the new armies is replaced by national suitability. Lack of social, political, and value assumptions for maintaining fighting morale results in (un)preparedness for fighting. The personality cult of Josip Broz was the foundation of political power, and the search for a replacement figure to establish a new personality cult in the form of former Yugoslav and Serbian president Slobodan Miloševič (used King of Yugoslavia and later Tito White Residence at Dedinje, YPA Guard Unit, armoured Mercedes), first president of Croatia Franjo Tudjman (appear in white Field Marshal uniform), first president of Slovenia Milan Kučan (leadership by secret deals behind the scene), lead only to risen popularity of Josip Broz – Tito.

The YPA was the last line of defence of the communist ideology; the new armies only replaced the communist ideology with a new nationalistic one.

Armies born out of YPA, Slovenian–because of short war not seen or detected at first look, Croatian, Bosnian Serbs, Bosnian Federation Army, Serbian Army, Montenegrian Army, Kosovo Army all inherited YPA organisational culture. The result may be a misalignment between the strategic culture of the new states and the organisational culture of defence systems, as in the case of Slovenia. A potential consequence could be the forms and methods of conducting any future war, which would be in significant patterns no different from the recent Balkan wars between 1991 and 1999.

Total People’s Defence Concept

The influence of the TPD&SSP concept on Slovenian Strategic culture will be addressed, which should promote self-awareness in international readers and alert us to the dangers of inertia (“that’s the way we’ve always done it”) and groupthink in policy development and decision-making.

The concept of TPD&SSP was developed in communist Yugoslavia during the 1960s as a response to the threat of foreign aggression and internal subversion. It aimed to mobilise the entire population for defence by decentralising military structures in Territorial Defence and combining civilian and military efforts. The system was integrated into all levels of communist society, ensuring national defence and defence of the communist system with the collectivisation of the defence area as a collective responsibility.

Communism as a state ideology was introduced after the Second World War in Eastern and some Central European Countries. Not all East European communist countries collapsed as Yugoslavia in the last decade of the 20th century; some, such as Czechoslovakia, disintegrated peacefully into two states, Czechia and Slovakia. One of the possible causes was described by Miroslav Hadžić. In most countries, communism was imported and violently maintained by Russian military forces occupation. The absence of collapse showed that communist ideology was not being integrated into the strategic culture, and it enabled the Eastern bloc states’ militaries, as in Poland or the Baltic States, to distance themselves emotionally from the communist system and ideology, allowing an easier ideological turn. Consequently, Eastern European countries were not involved and destroyed by wars by their armies as in the Yugoslavian case where YPA found themselves as armed guardian of revolution and communist system. The ideologies of socio-revolutionary authenticity, as in the Slovenian and Yugoslavian cases, built their faith in the eternity of the revolutionary army, communism, and power on this fact.[6]

The ideologies of socio-revolutionary authenticity, as in the Slovenian and Yugoslavian cases, built their faith in the eternity of the revolutionary army, communism, and power on this fact.

Davor Marjan examined the TPD&SSP system. Values are the roots of strategic culture, particularly in the Slovenian case; the primary value of “revolutionary character “best describes Total People’s defence system. Political revolution and inherited “character or strategic personality” during World War 2 in Yugoslavia and Slovenia was accompanied by “social revolutions” in which old property relations in the form of capitalism were overturned with communism. Tito’s speech summarised revolutionary tradition in TPD&SSP: “The concept of total people’s defence is nothing but a consistent and decisive application of the experience of the national liberation war in the present circumstances.”[7] The Yugoslav and Slovenian National Liberation War 1941-1945 included a Leninist type of communist revolution parallel with civil war.

Furthermore, the introduction of defence studies to the central universities of the second Yugoslavia resulted from the doctrine of total people’s defence and societal self-protection. The total people’s defence concept was based on the defensive socialisation of citizens through education. After 35 years, nothing much has changed in defence education.

Social and Cultural Shifts in the form of democracy versus working people dictatorship societal norms, values, and diversity awareness would require a push for inclusive, equitable education and updated curricula that reflect everyday European realities. For 30 years, the Slovenian state or government coalitions have not been able to build accredited Professional Military Education (PME) institutions and programs. Marjan Malešič, a long-term member of the Defence Research Centre at the University of Ljubljana and professor at the Faculty for Social Sciences, described development at a Slovenian university: “A key point in the process of creating scientific knowledge was the abandonment of the word ‘total people’s defence and societal self-protection’ and the introduction of the term ‘defence studies’”.[8] The renaming program alone cannot shape and modernise education systems from mainly TPD&SSP based on communist ideology. An understanding of our past and new curricula with a new democracy-oriented orientation must be introduced to set the condition for the strategic culture change process to evolve with ethical and straightforward extremisms.

Defence or “Talking” Strategy

A critical note on the Slovenian Defence Strategy will be presented using Richard Rummelt’s characteristics of bad strategy.[9] In the book Good Bad Strategy, grandiose phrasing and vocabulary create an illusion of expertise that does not correctly define the specific challenge. It fails to narrow down the Defence Strategy scope. Dubious objectives and the absence of implementation guidance distinguish good from bad strategies.

Strategy is an assumption about theory and approach outlining how to reach long-term objectives. The overall Republic of Slovenia defence concept described in the Defence Strategy from April 2024 appear to be modern and aligned with collective defence; it is still connected with the total people’s defence concept while referring to the success of the Slovenian Independence War of 1991 and defence concept in place that time. The idea of total people’s defence is antithetical and does not coincide with the concept of collective defence. With the new April 2024 defence strategy, the Republic of Slovenia has goodwill for upgrading the processes and activities of the whole defence system, adapting to the current and possible security conditions at the national level and in NATO and the European Union. Slovenian Defence strategy from 2024 in the introduction part relies on vocabulary to create an illusion of expertise and dangerously connects with strategic culture from the last Balkan wars, characterised by ethnic cleansing, breaking the rules of international laws as follows: “It also draws from the experience of the war of independence in 1991, when it was at a high-level defence preparedness of the country and the operation of the Territorial Defence and the police”.[10] Grandiosity refers to a sense of specialness and self-importance. The reality is that Slovenia is a small, less critical alliance member, and the Defence Strategy should be based on that. As an alliance member, your contribution to common defence is important, as well as an explanation of how common defence will work.

Strategy is an assumption about theory and approach outlining how to reach long-term objectives.

In the second part of the Defence Strategy, the international security environment of the Republic of Slovenia is described from a nonalignment perspective. Second, Yugoslavia was an important part of the nonalignment movement, and Tito was one of the founding fathers. Mental operating system or strategic culture still today in that period emphasises international organisation first and Alliance as only an addition: “Taking into account international law and the principles of the United Nations and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the Republic of Slovenia will continue to commit and advocate for and contribute to ensuring international peace, security and stability in the future. The most important entities in the Euro-Atlantic area will continue to be NATO and the European Union”.[11]

The Republic of Slovenia has been a NATO member since 2004, and this paragraph points out that NATO is a framework rather than the most important single element of Slovenian defence. Whether the EU can establish a strategic culture or “strategic personality” is debatable. Optimists contend that there are signs that European strategic culture is already developing through socialisation. Pessimists, the Slovenian case is in support, charging that Europe lacks the capabilities and will to establish a common foreign and security policy in the foreseeable future.

The Defence Strategy does not correctly define the specific challenge Slovenia faces in the defence area. When the problem is not explicitly named, it can’t be adequately addressed: “Since 2010, it has been possible to detect a pronounced destabilisation of the Middle East, which was increased by the War in Gaza. The conflict in the Red Sea and the destabilisation of North and Sub-Saharan Africa, dominated by local and regional asymmetric threats, accelerate destabilisation and cause a resource security threat to Europe. A similar trend has also been in Eastern Europe since 2014. After the outbreak of the War in Ukraine in 2022, relations between the West and Russia worsened, and as a result, the risk of an outbreak of a very large-scale armed conflict has also increased.”[12]

After the outbreak of the War in Ukraine in 2022, relations between the West and Russia worsened, and as a result, the risk of an outbreak of a very large-scale armed conflict has also increased.

The Defence Strategy addresses Russia not as an enemy but as a cause for worsening relations with the West. As a NATO member, Slovenia is participating in great power competition with Russia as a member of Western democratic Euro-Atlantic states. Furthermore, Russia explicitly stated in 2022 that NATO should continue before the 1997 design, which means that while Slovenia joined in 2004, Russia believes it should leave NATO. The defence strategy focuses on peace and security goals instead of collective deterrence and defence methods to overcome challenges.[13]

The defence policy of the Republic of Slovenia is described in paragraph four of the Defence Strategy, but there are no objectives or guidance for achieving goals. Instead of ways, significant activities and programs to achieve objectives, only principles and background “The purpose” as a basis for Defence policy is described;” The purpose of the defence policy of the Republic of Slovenia is to provide optimal ways. It means for their realisation based on the defined interests and goals of the country in the field of defence and the assessment and evaluation of threats and risks to national security”.[14]

The defence strategy fails to narrow its scope, instead focusing on too many objectives or, as in the Slovenian case, many objectives summarised in one line. For example, Slovenia cannot deter military Russia; it can only be part of an alliance deterrent strategy and related programs or significant activities. It also sets unrealistically ambitious objectives but does not provide helpful guidance on how to achieve them: “The Republic of Slovenia will assert its defence interests by realising defence goals:

- deter military and other threats and risks to the national, collective, and common security;

- to defend the independence and territorial integrity of the country and interests within the framework of collective and common defence;

- to ensure the uninterrupted functioning of the state and society”.[15]

Defence goals for a small central European country member of NATO and the EU would be developing a niche element of Joint Forces, maintaining a regional balance of power where Croatia and Serbia are involved in a regional arms race, and changing the TPD&SSP defence mindset.

Citizens could learn about implementation guidance presented as based on the Defence Strategy in one of the government-affiliated web portals. The government party’s interpretation mentioned before shows how the total people’s defence system and ideology in support are ironed in strategic culture. Likely, it is a failure of civilian and parliament control of the military from a functioning democratic point of view to have a defence strategy and implementation guidance that is not aligned with the guidance published in the portal affiliated with a particular government party. Parliament should approve laws and strategies, and the government should implement them. Political parties who “own” the Defence area interpret defence strategy in their own way, as was one of the features of communism, where a one-party system allows no civilian and parliamentary control. Theoretical starting points, according to Samuel Huntington,[16] argue that civilian control over the armed forces requires high military professionalism and officers’ awareness of the limitations of professional competence, effective subordination of the army to elected civil officials, and recognition of the civilian authority’s professional competence and the army’s autonomy. The ruling elite must not be allowed to freely use the military for their internal or external political goals, as in the Slovenian case. On the other hand, it is necessary to prevent the military’s political interference so that the military elites do not impose narrow corporate interests on society. There is no army or generals elite in Slovenia, so, no even option for generals to interfere in politics.

Consequently, instead of developing the Slovenian Armed Forces (SAF) and Defence System for Collective Defence, defence officials, with the support of SAF leadership, built their army in line to practice the TPD&SSP concept.

The article focused on shaping the mind of the Minister for Defence and inform citizens about way, from the magazine “Mladina”: “Program on how to invest two per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in defence without buying weapons consist of projects: Military windmills 60 million EUR, Military housing 100 million EUR, Military two-way rail track 50 million EUR and 15 missiles land air less, Military second rail track 353 million EUR, Military stadium 20 million EUR and 16 surface-to-air missiles less, Military hospital 305 million EUR, Military farms, and military bees 5 million EUR and one 8×8 less”.[17] From a technical point of view, the article develops some elements, particularly programs and fewer activities, of a good strategy compared to the actual Defence Strategy. However, from a national security point of view, it misleads citizens and shows that civilian and parliament control is not working.

Conflating goals and strategy shows incompetency and an absence of strategic thinking. If the strategy is deterrence, the goal should be a means of capability, e.g. air defence, to allow deterrence to work. In the case of Slovenian, the goal is to develop and employ allies’ agreed capabilities in Slovenian case two manoeuvre battalions. Not to be precise, allow muddling through the defence area. Young noted one of the main characteristics of conflating goals with strategy. “The problem is that the policy framework remains ‘cast in concrete’. Policymakers still struggle to link policies and priorities. The worst part is that by spending a lot of money on training people, you’ll have a great opportunity to know how to solve problems you’ll never have”.[18]

The problem is that the policy framework remains ‘cast in concrete’. Policymakers still struggle to link policies and priorities.

In support of Young’s statement, after 20 years, Slovenian policy still has no priority in developing and employing two mechanised battalions. Having in place two equipped and trained according to NATO standards battalions Slovenia could contribute to alliance deterrence and defence. Not having that other alliance member must take the Slovenian burden. In case of absence or poor plans for transforming the Slovenian Armed Forces, the army and the leadership are left to self-transformation outside the public view. Practice reduces the possibilities for the rational regulation of civil-military relations and the appropriate transformation of the inherited military organisation.

The Slovenian defence strategy was developed by an expert group and overseen by the ministry’s leadership. However, after its presentation to the parliamentary defence committee and government approval, the implementation does not follow a written or “talking strategy”, namely the execution of key programs and activities. Still, it follows its logic based on the mindset of TPD&SSP or “acting strategy”. The defence strategy should address military capabilities in deterrence and defence by specifying areas of engagement and strategic partners such as the United States and Italy and neighbouring allies Hungary and Croatia, with neutral Austria. In the case of increasing societal resilience, specific areas such as critical infrastructure or societal resilience are to be addressed with concrete programs to achieve the goals, which are also financially evaluated.

Total People’s Defence Myth

The loss of the Yugoslav threat in 2000 led to a divergence. The larger population, politicians, and Yugoslav officers, either from YPA or Territorial Defence, still viewed territorial defence as the core task of the SAF. At the same time, the NATO-aligned leading elite in the military profession held international operations, deterrence, and defence of the interests of the Euro-Atlantic area as the core task. Slovenian strategic culture changed from a preference for homeland defence to a preference for international operations as the core task.

The NATO-aligned leading elite in the military profession held international operations, deterrence, and defence of the interests of the Euro-Atlantic area as the core task.

The general characteristic of assessing the success and effectiveness of the Yugoslav strategy of TPD&SSP is that it is lacking. Typically, the written part consists either of the memoirs of leading politicians and generals from that period or testimonies of the accused and witnesses before the Hague Tribunal for war crimes in the former Yugoslavia. The historical results or outputs of the TPD&SSP concept in other parts or now new states formed on the territory of Second Yugoslavia are not mentioned or examined by either Defence Strategy authors or academic institutions. Several politicians such as Borisav Jovič, Stjepan Mesić, Milovan Djilas and Franjo Tudjman, authors such as Sabrina Ramet and Walter Roberts, journalists present and reporting from 1990 to 1999 from the area as Tim Marshall and Tim Judah, as well as generals Veljko Kadijevič and Konrad Kolšek examine causes, development and finish of last Balkan wars drama in memoirs or books, but no one address successes or failures of TPD&SSP concept from military point of view. The former explain their roles and justify their decisions and actions, while the latter justify the procedures and adherence to international laws of war. In the case of Slovenia, a general conclusion is drawn that the strategy successfully defended the territory and independence, which is generalised to the entire strategy based on the concept of total people’s defence. No one questions why the strategy did not work in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, or Serbia, and conclusions are then formed examining all wars for the dissolution of the Second Yugoslavia.

Furthermore, you will not find an analysis that will underline the differences between people’s defence concept and the Scandinavian type of Total Defence concept. Scandinavian model lacks “people” in Total Defence. People are connected to socialism and the defence of the socialist system and not to the state’s defence. In 1991, YPA and its generals did not defend Second Yugoslavia as a state. They defended socialism. To learn about the level of understanding of TPD&SSP, is there an explanation note made by Hadžić: “What binds the new old armies together is the silence about the YPA. There is the evident lack of fundamental documents, including internal analyses of the military-political and social nature of the YPA, and thus the essence and cause of its military engagement, which ended with its disbandment”.[19]

No professional military education institution and/or program established by the Slovenian state integrated into the state public education system, or think tanks on the military science area or scientific event shadowing Theresan Military Academic Forum to deeply examine one of the pending issues related to contemporary wars. Consequently, citizens cannot be better prepared to understand the causes and effects of the government and political parties’ programs and actions in the defence area. So, citizens must note and understand the consequences of the type of warfare the government is preparing for with the Defence Strategy and Ministry of Defence activities. To stick with the declared policy of NATO Collective Defence, citizens can expect manoeuvre warfare. To follow the Total People’s Defence policy, they should be allowed to learn that they can expect attrition warfare, similar to one Europeans experienced in the Balkan in the 1990s.

No professional military education institution and/or program established by the Slovenian state integrated into the state public education system, or think tanks on the military science area or scientific event shadowing Theresan Military Academic Forum to deeply examine one of the pending issues related to contemporary wars.

Finally, silence about YPA and without the possibility of citizens learning and practising PME, the war from 1991 has become mythologised; there are many 1991 war analyses, but they are mainly emotional and delivered or repeated from a political level: “We won this war, even though everyone from the outside told us that it was a story doomed to failure,” emphasised Damir Črnčec as the State Secretary at Ministry of Defence.[20]

To properly understand the statements above, it should be noted that related battles and engagements in 1991 were planned and conducted, not simulated, on the tactical and operational levels. The Slovenian Territorial Defence Forces’ performance was excellent on the tactical level. From today’s perspective, fighting at the tactical level helped Serbs adapt and transform YPA for decade-long wars in the Balkan theatre.

Only by using one reliable source, which demonstrates rigour linkage between strategic culture and actual behaviour, out of Slovenia, can one find facts different from the prevailing narrative in Slovenia. Those who serve citizens or do academic research must consider all relevant facts when interpreting and using War for Independence 1991 to avoid being biased by ideological interpretation: “In January 1991, a secret agreement between Serbia and Slovenia was concluded. Slobodan Milošević signalled to Milan Kučan that the Slovenians could leave Yugoslavia if they did not hinder Serbian plans regarding the rest of Yugoslavia”.[21]

Since wars are won or lost at the strategic level, the agreement between Milan Kučan and Slobodan Milošević signalled, if not set, the outcome of the Slovenian War of Independence. At the very least, it requires a comprehensive investigation and independent interpretation of the effectiveness of the concept of TPD&SSP; the Slovenian case included was perceived as only success.

The candidate for Defence Minister in 2022 stated: “The defence concept must be changed. Among his first tasks at the Ministry of Defence, he will tackle changes to the concept of defence policy”.[22] Considering what we know about the TPD&SSP concept and related strategic culture statements, it is unsurprising.

The positive attitude to the mythologise Total People’s Defence concept of the parliamentarian coalition government’s most prominent political party was shared by Miroslav Gregorič at the parliament committee for Defence examining Defence Strategy, who stated that: “The defence and military strategy are equally important documents, but added that an action plan with a timeline is missing. I want the Slovenian army to have 20.000 professional soldiers and 120,000 reservists.”[23] One can conclude that a Cold War-type mass military is an end state.

I want the Slovenian army to have 20.000 professional soldiers and 120,000 reservists…

A mental operation system or strategic culture in the TPD&SSP concept shapes the Acting Strategy. Not surprisingly, from a strategic cultural perspective, the communist common practice was that the party central committee decided. However, the implementation used decisions only as suggestions and likely nothing has changed on the ground. Defence Strategy is based on the Collective Defence Concept and was published by the Slovenian Government Gazette when approved. Guidance on how to put Defence Strategy goals into reality is published in the web portal and is based on the TPD&SSP concept; consequently, misinformed citizens. They are published during government approval of the Defence Strategy and not in line with the Strategy, first with a conceptual or ideological introduction: “By joining NATO, we forgot about total people’s defence concept. We went toward a professional army with a contractual reserve, an army that does not have these clear depth reserves. The abolition of conscription in 2003 also contributed to this”.[24]

The new and old armies are linked by the silence about the YPA, as evidenced by the absence of sociological and military-political analyses. So, the TPD&SSP concept’s main line can be presented as a “golden solution” to citizens and critics only as heretics. The YPA was the last line of defence of the communist ideology; the new armies only replaced the communist ideology with a new one. Party-political suitability is a criterion for selecting candidates; the criterion in the new armies is replaced by national suitability. Lack of social, political and value assumptions for maintaining fighting morale resulted in (un)preparedness for fighting. The personality cult of Josip Broz was the foundation of political power in Yugoslavia. The failed search for a replacement figure to establish a personality cult in new states born out of Yugoslavia’s dissolution only raised Josip Broz’s popularity even nowadays.

Slovenian Strategic Culture Dubious Results

As a broad summary of the evolution of Slovenian defence in the post-Cold War era, one could say that Slovenia has gone from being capable of mobilising close to 70.000 citizens for the defence of the country to lacking the ability to mobilise a planned 10.000 soldiers with the same Slovenian “mental operation system” or Strategic culture in place.

NATO’s Strategic Concept 2022 describes conditions for adaptation to the new security environment marked with great power competition and was adopted by Heads of State and Government at the NATO Summit in Madrid on June 29, 2022. One of the authors of the NATO Strategic Concept, Stephen Covington, argues that it made “the background for Deterrence and Defence of Euro Atlantic Area implementation, which is based on Modernised Plans, Forces, Alert System, Command and Control, and Exercises.”[25]

As long as Slovenia does not develop two manoeuvre battalion groups, it cannot take over responsibility inside NATO’s deterrence and defence role and cannot execute a collective defence strategy. Without combat-ready battalions or forces, Slovenia cannot participate in NATO exercises and execute modernised plans, fully implement the NATO alert system, or be integrated into NATO command and control on a tactical level.

As long as Slovenia does not develop two manoeuvre battalion groups, it cannot take over responsibility inside NATO’s deterrence and defence role and cannot execute a collective defence strategy.

To enforce the above, the NATO Defence Planning Staff notes the long-term results of the Slovenian Defence Plan. It describes them in NATO’s assessment of Slovenian Defence System capacities: “Slovenia states that its main priority in terms of capabilities is the creation of two medium battalion battle groups. In practice, this priority is challenging to identify. Even the opposite; it could be concluded that the defence planning priorities of Slovenia and NATO are not coordinated.”[26]

The Slovenian prime minister, whose government, at the beginning of the mandate, broke the signed contract to buy 40 Armoured Fighting Vehicles for one battalion alongside the NATO summit, stated: “The government performed a new calculation and adopted amendments to the Development Program Plan 2023-2026. Instead of purchasing boxers worth 412 million EUR, a new project was planned, which envisages the purchase of 106 combat-wheeled 8×8 vehicles with a starting price of 695.2 million EUR, including VAT. According to the government’s calculations, this should save 498 million EUR, or about 3.5 million EUR per vehicle, if you decided to buy Finnish Patria.”[27]

New calculations put in place money-related narratives with the intent to fix immaterial problems by delaying strategic investment and misleading citizens with false narratives. Material investments are often profoundly appreciated by the population but not those related to military capabilities. Dominating in the mental or cognitive domain is the only way to protect the longevity of communist practices. The new calculation represents a misleading strategy in the era of high inflation and increased demand due to the Russo-Ukrainian War, which means more expenses for the same or worse quality armoured fighting vehicles (AFV). Acting Strategy based on Total People’s Defence strategic culture will postpone the purchase of AFVs and is likely designed only to show the Allies Slovenian government goodwill.

A Long Way to Go

Strategic culture can change as new experience is absorbed, coded, and culturally translated. Culture, however, changes slowly. Finetuning and fundamental change are options. There are four main approaches to understanding and analysing strategic culture.[28] The first contextual approach emerged in the 1970s, emphasising the influence of a nation’s history, geography, and political culture on its strategic behaviour. The paper begins with this tradition, focusing on the deep-seated cultural, historical, and geographic factors influencing the Slovenian state’s decision-making in security matters.

Strategic culture can change as new experience is absorbed, coded, and culturally translated.

To emphasise tradition still alive today, in an article published by the Slovenian Armed Force’s leading professional and scientific publication by Igor Kotnik, one of the authors of the April 2024 Defence Strategy noted historical and geographical factors that influence Slovenian state decision-making: “In conceptual terms, the downsizing and restructuring of the SAF culminated in 2010 with the abolition of the compulsory military reserve and the Military Territorial Commands. The abolition of the compulsory military reserve reflected the peak of utopian idealism about transforming the military organisations of developed industrialised countries into post-modern expeditionary forces.”[29] Developing Military Territorial Commands with number or non-territorial units or empty ones is an activity to reinforce the TPD&SSP concept. So, the reimplementation of the TPD&SSP is ongoing. Combat-ready battalions in support of Collective Defence are seen from the Defence Strategy writer’s perspective as “utopian idealism”.

The second generation or school of thought, the constructivist approach, shifts the focus toward the role of ideas, beliefs, and identity in shaping strategic culture. This approach emphasises the importance of norms, symbols, and discourse in how strategic behaviour is developed and maintained over time.

One of the main pillars of YPA combat readiness was communist morale. The SAF evaluated itself as not being ready for combat for a decade now but is prepared for non-combat missions and tasks at home, which shows the primacy of ideology over the profession, permanently disabled the SAF militarily and politically. Even though the ordinary communist/socialist and Yugoslav history has been discarded, the foundations of the Power Generation System are still in place and have not been removed. The YPA’s genetic attachment to socialism and revolution made it a predominantly ideological institution. Consequently, the total people’s defence concept with an attrition approach was tragic in the decade-long Balkan wars of the 1990s.

The third generation of the strategic culture school of thought, the behaviour approach, looks at strategic culture from a more empirical and behavioural perspective. It focuses on how decision-makers within a state perceive threats and opportunities based on their cultural predispositions. The behavioural approach emphasises decision-making processes, organisational behaviour, and psychological factors. In the Defence Strategy part, the behaviour and decision-making process were examined. In addition, if the defence strategy purpose failed to address Tucker’s Defence System purpose requirements, it should be considered: “Purpose must provide the unifying focus for military theory and doctrine. Political policy, which provides the purpose, also determines the ways and means available to the military to accomplish its tasks. Policy determines where and for what purpose military force will be brought to bear.”[30]

Purpose must provide the unifying focus for military theory and doctrine. Political policy, which provides the purpose, also determines the ways and means available to the military to accomplish its tasks.

The first three schools or approaches’ inability to explain the change in strategic culture led to the fourth generation. Subculture studies became central, implying that knowing the context is essential for studying change. The United States of America Marine Corps doctrinal publication argues that each nation, state, or political entity has its distinct character. This character is derived from various sources: location, language, culture, religion, historical circumstances, etc. While a national character constantly evolves, changes occur only over decades and centuries and may be imperceptible to the outside observer. As such, national character can be considered a norm or constant.[31] National character and related strategic culture are difficult to change. A common agreement based on observation is that massive external political events, such as the communist revolution during the Second World War in Slovenia and/or the military collapse of the German Army after the Second World War, may alter the historical makeup of a state’s strategic culture.

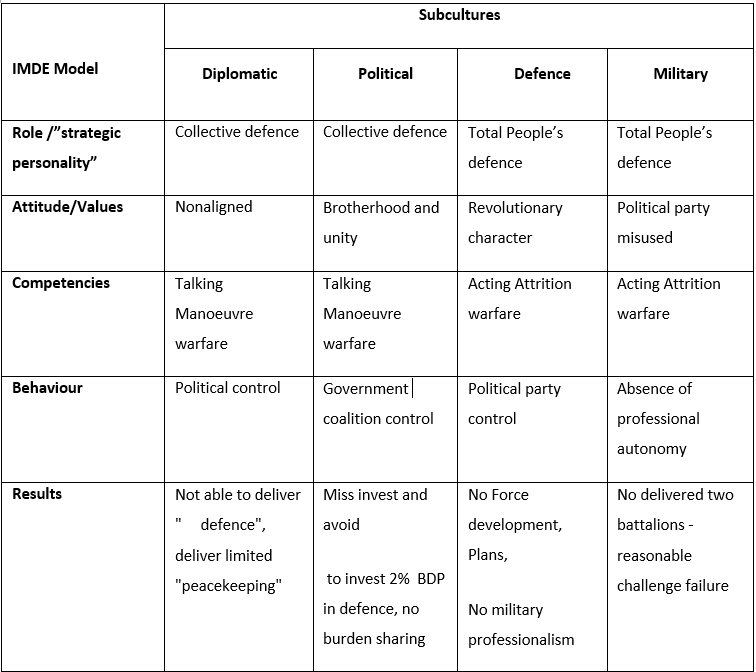

Posture and attitude change theoretical model by Swiss IMDE Company applied to Slovenian Strategic Culture “Subcultures”.

An officer’s academic culture could also be rated organisational when states have independent education systems. However, the officer academic subculture does not exist in Slovenia.

Posture refers to the physical or tangible elements of a state’s strategy. It concerns the capabilities, deployment, and preparedness a state or military maintains to respond to threats or opportunities. On the other hand, attitude refers to a state or organisation’s expressed intentions, beliefs, or rhetoric. It represents how a state communicates its strategic outlook, values, and objectives through diplomacy, public statements, or negotiations. The posture and attitude of a state can either be aligned or divergent. An alignment between posture and attitude indicates that a state’s words and actions are consistent. At the same time, a divergence, as in the Slovenian case, suggests a strategic slack, incompetency or inability.

Conclusions and Recommendation

As was the case during the Second World War, a decade-long period of strategic shock was required to reorient Slovenian strategic culture. A typical component of Central European culture, especially in the Alpine world, is almost overwhelming hard work, discipline, and a positive attitude towards work as an attitude to life.[32] Due to historical circumstances, entrepreneurship, which would foster society relearning central European cultural values and processes and set the ground for strategic culture change, is less emphasised. A decentralised approach, such as entrepreneurship, can speed up cultural change. Half a century of life under communism led to a noticeable departure from these character traits.[33]

The ability of post-communist and socialist Slovenian defence institutions to transform in line with the collective defence concept and democratic governance is weak. Two concepts – collective defence and total people’s defence – ended with meagre results in the defence field, exposing the state to different threats. The principle of total people’s defence tied to societal defence remains a real, if not legal, dominant operational (and mental) concept, which intentionally undermines the principle of collective defence and the foundation of the North Atlantic Alliance. State defence strategy and military strategy are not aligned; defending with total people’s defence is even dangerous, taking into account the Ottoman Empire and Second Yugoslavia’s bloody wars of dissolutions.

The ability of post-communist and socialist Slovenian defence institutions to transform in line with the collective defence concept and democratic governance is weak.

The way communism and socialism operated was on the fundamental principle of absolute, unpredictable, and irresponsible party power. Consequently, civil and parliamentary control is dangerously underdeveloped, and malpractice, say, in defence strategy, is one thing and reward with implementation in defence area another not aligned or directed by strategy. The collective defence concept was challenging to understand and implement in the Slovenian environment. To someone who grew up in a communist environment, money is not perceived as the essential tool for managing an organisation; it is mainly used to pay salaries, contributions, and pensions. Nonalignment and mental self-sufficiency still generate doubts about the values of Allies in collective defence, even if the concept was successful in the First and Second World Wars and the Cold War.

The reader should note that the changes in defence have not only meant a change in force structure or reorganisation of the defence sector under pressure from economic austerity, as in the Slovenian case, but above all, a conceptual change, a change of defence policy, doctrine, and strategy.

In conclusion, it can be argued that a significant Slovenian Defence Strategy—Slovenian Strategic Culture gap is observed. Total people’s defence vs. collective defence culture identity can produce different types of war and related capabilities. Defence Strategy is based on the collective defence concept related to the NATO manoeuvre approach as a way of war. Strategic culture-based Slovenian defence policy influenced by the legacy TPS/SSP concept as a way of war can produce revolutionary war and related attrition approach in the 21st century in Europe, too.

Addressing those problematic challenges will require collective defence concept-based strategic communication and actions, with government responsible behaviour towards Slovenian citizens. This will close the gap between Talking and Acting Defence Strategies. The result will increase citizens’ and state trust as a baseline for strategic culture change.

According to the fourth-generation strategic culture school, a gradual strategic culture change could involve a transition from a trained officer’s corps to an academic one. Individual and later collective capability for independent and critical assessment, distinguishing, formulating, and solving problems, meeting change in the workplace, and searching for and valuing knowledge on a scientific level to follow warfare development could make Defence more relevant.

With its undeveloped education in military sciences for both military and defence professionals and citizens, the Slovenian state is exposed to the risk of who will lead and participate in the next war and how it will be conducted. The following saying well describes a hundred years way of war and strategic culture in the region:

As by the rule in the last Balkan wars, military art and profession were substituted with brutality and the absence of any civilised customs of war while based on a historical national mindset. Moreover, there is a warning message while SAF inherits the YPA character, no reorientation is implemented. There is a high probability that SAF, during the future war, will behave as YPA. YPA exposed itself as an ideological organisation of revolutionary conservatism and, as is shown in the Total People’s Defence model, revolutionary character, which is still present in SAF and Slovenian defence area-related discourse.

As by the rule in the last Balkan wars, military art and profession were substituted with brutality and the absence of any civilised customs of war while based on a historical national mindset.

It should be mentioned that addressing long-standing narrative imbalances will require a lot of political courage from citizens, defence and military professionals, and government and defence ministers. Only after public perception changes will the Slovenian armed forces be in a position to deal with imbalances such as hollow units, high-intensity combat training, and the lack of modern combat systems.

Captain(N) Peter Papler holds a Master’s degree in Business and Organization (2005) and a Ph.D. in Defence Studies (2014) from the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. The research statement and teaching portfolio include Strategy, Strategic Leadership, and Management. The latest presentation at the ISMS Conference is “Hacking Strategy” (2023). The views contained in this article are the author’s own and do not represent the views of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the Slovenian Armed Forces or the Ministry of Defence.

[1] Lawrence Sondhaus, Strategic Culture and Ways of War (New York: Routledge, 2006), 9.

[2] Carl von Clausewitz, O ratu (Zagreb: Ministarstvo obrane Republike Hrvatske, 1997), 502-503.

[3] Tim Dzuda, Srbi, Istorija, mit in razaranje Jugoslavije (Beograd: Dan Graf d.o.o., 2003), 75.

[4] Miroslav Hadžić, Sudbina partijske vojske (Beograd: Samizdat B92, 2001), 136.

[5] Ibid., 175.

[6] Miroslav Hadžić, Sudbina partijske vojske (Beograd: Samizdat B92, 2001), 160.

[7] Davor Marjan, “Koncepcija općenarodne obrane in društvene samozaštite – militarizam samoupravnog socijalizma,” Septembar 09, 2021, https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/388135.

[8] Marjan Malešič, “Aktualna vprašanja razvoja obramboslovja,” Teorija in praksa let 50.2/2013, Ljubljana.

[9] Richard Rummelt, Good Strategy Bad Strategy, The difference and why it matters (New York City: CPI Group Ltd, 2017), 77-78.

[10] Vlada Republike Slovenije, Obrambna Strategija, https://www.gov.si/assets/ministrstva/MO/Dokumenti/OS_8n_sprejeta_24_4_2024.pdf.

[11] Idem.

[12] Idem.

[13] Thomas Graham, What Does Putin really want in Ukraine, Council on Foreign Relations, https://www.cfr.org/expert-brief/what-does-putin-really-want-ukraine, May 16, 2024.

[14] Vlada Republike Slovenije, Obrambna Strategija, https://www.gov.si/assets/ministrstva/MO/Dokumenti/OS_8n_sprejeta_24_4_2024.pdf

[15] Ibid.

[16] Samuel P. Huntington, The Soldier and the State, The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), 80-97.

[17] Borut Mekina, Let’s screw up Nato; how to invest two per cent of GDP in defence without buying weapons?, July 26, 2024, Mladina 30.

[18] Thomas Durell Young, Interviju Revija Slovenska Vojska, April 2018, https://www.slovenskavojska.si/medijsko-sredisce/publikacije/slovenska-vojska-v-drugih-publikacijah/.

[19] Ibid., 175.

[20] Aleksander Kolednik, Aleš Žužek, Mihael Šuštaršič, “Pozabljena lekcija iz leta 1991, ko smo Slovenci pregnali okupatorja,” January 20, 2024, https://siol.net/novice/slovenija/pozabljena-lekcija-iz-leta-1991-ko-smo-slovenci-pregnali-okupatorja-624786.

[21] Tim Dzuda, Srbi, Istorija, mit in razaranje Jugoslavije (Beograd: Dan Graf d.o.o., 2003), 154.

[22] G. K., Al. Ma., “Po mnenju odbora Šarec, ki se želi vrniti k Teritorialni obrambi, primeren kandidat, May 30, 2022, https://www.rtvslo.si/slovenija/po-mnenju-odbora-sarec-ki-se-zeli-vrniti-k-teritorialni-obrambi-primeren-kandidat/629129.

[23] Aleksander Kolednik, Aleš Žužek, Mihael Šuštaršič, “Pozabljena lekcija iz leta 1991, ko smo Slovenci pregnali okupatorja,” January 20, 2024, https://siol.net/novice/slovenija/pozabljena-lekcija-iz-leta-1991-ko-smo-slovenci-pregnali-okupatorja-624786.

[24] Idem.

[25] Stephen R. Covington, “NATO’s Concept for Deterrence and Defence of the Euro-Atlantic Area (DDA),” August 02, 2023, https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/natos-concept-deterrence-and-defence-euro-atlantic-area-dda.

[26] NATO defence planning, “Pregled zmogljivosti Slovenije 2019/2020,” October 18, 2020, https://www-gov-si.translate.goog/novice/2020-12-18-pregled-zmogljivosti-slovenije-20192020-v-okviru-natovega-obrambnega-nacrtovanja/?_x_tr_sl=sl&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc.

[27] M.V., 24ur, Ljubljana, 11. 07. 2024(Pre)dragi boxerji in vrnitev k Patrii, (Pre)dragi boxerji in vrnitev k Patrii | 24ur.com.

[28] Lawrence Sondhaus, Strategic Culture and Ways of War (New York: Routledge, 2006), 1-13.

[29] Igor Kotnik, “20 years of Republic of Slovenia in NATO: Some impressions about the tiny part and the whole,” Contemporary Military Challenges 26/1, 2024, 71-75.

[30] Craig A. Tucker, False prophets: The Myth of Manoeuvre warfare and the inadequacies of FMFM-1 Warfighting (Fort Leavenworth, United States Army Command and General Staff College, 1995), 28.

[31] Department of the Navy, Strategy (Washington D.C.: U.S. Marine Core HQ, 2018).

[32] France Bučar, Prehod čez rdeče morje (Ljubljana: Mihelač, 1993), 115-119.

[33] Idem.