Abstract: Major Pete Ellis shaped the United States Marine Corps with his mentor, General John Archer Lejeune. Marine Commandant Lejeune utilised Ellis’s works to define the future of the Marine Corps. Ellis also influenced the United States Navy and the United States Army with his amphibious operational theory. Like the 1940s, the United States military confronts a near-peer in the Indo-Pacific region while ill-prepared for war.

Marine Major Pete Ellis is essential to understanding the Marine Corp’s amphibious development, and Ellis remains relevant. Since Ellis was a visionary, the Marine Corps needs to continue to evaluate Ellis’s notions and apply any concepts that would strengthen the military.

Problem statement: How did Major Pete Ellis’s amphibious operational theory impact the Marine Corps, and what Ellis’s concepts should the Marine Corps apply in the 21st century?

So what?: The Ellis Group (Marine Corps think tank) and the United States Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory need to review Ellis’s ideas and utilise the concepts as launching points for the Marine Corps of the 21st century. The Marine Commandant must listen to his combat-experienced Marines and not throw out old tactics and strategies that were successful before, such as the Corps not having tanks anymore. With the tanks, Marine platoons shot flamethrowers to reveal well-hidden enemies. If the Marines have to wait for the Army to bring a tank, the Marines become high-risk targets.

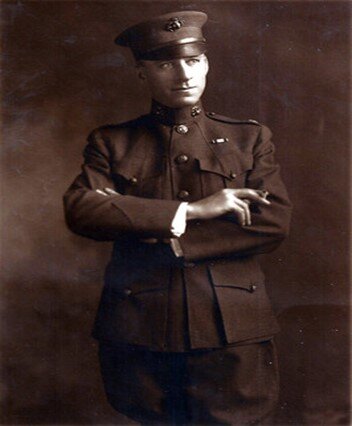

Earl H. “Pete” Ellis Collection (COLL/3246); Courtesy of the Archives Branch, Marine Corps History Division, https://www.flickr.com/photos/usmcarchives/49757290627/in/album-72157710446176952/.

An Overlooked Marine Officer

After the Spanish-American War (1898), the victorious United States became recognised as an emerging power after the United States Navy and Marine Corps demonstrated its dominance and strength. Sixteen years later, Marine Commandant George Barnett sent Marine officers to observe European military organisation, weapons, and tactics occurring in the first year of World War I. Colonel John Archer Lejeune led the European studies, and Lejeune and his staff continued the examinations throughout 1915.[1] During this time, Major Earl Hancock Ellis (Pete), as the aide-de-camp to Commandant Barnett, developed a friendship with Lejeune. Two years later, President Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany and appointed General John Pershing to command the American Expeditionary Force. Commandant Barnett, meanwhile, convinced the Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels, to permit one Marine Brigade to deploy with the Army’s American Expeditionary Force (AEF) to France. For Lejeune and Ellis, the Great War illustrated their leadership and vision. Once the Great War ended in 1918, Lejeune received the honour and responsibility of the Marine Commandant. As part of Lejeune’s staff, Ellis became Lejeune’s protégé.

Marine Commandant George Barnett sent Marine officers to observe European military organisation, weapons, and tactics occurring in the first year of World War I.

Lejeune sent Ellis on a special mission to the Far East. When Ellis returned, he wrote his amphibious operational theory and titled the document “Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia.”[2] However, Ellis’s untimely death provided Marine General Holland Smith an opportunity to become the face of amphibious operations of World War II since he was the commander of the V Amphibious Corps.[3] Although Ellis remains obscure, “Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia” became the cornerstone of amphibious operational doctrine, shaped the island-hopping strategy of the Pacific, and started the transformation of the United States Marine Corps.

As a visionary, Major Pete Ellis remains an overlooked Marine officer. Since Ellis was the director of the intelligence section of the Division of Operations and Training (DOT), he had a vital role in forming the present-day United States Marine Corps (USMC). Acting Editor, B.A. Friedman compiled 21st Century Ellis: Operational Art and Strategic Prophecy for the Modern Era, which showcases several documents penned by Ellis. Friedman states, “While Ellis’ works were prescient in his time and ours, he was hugely influential in the creation of the modern United States Marine Corps. The father of the modern Corps is Gen. John A. Lejeune, but it is the ideas and intellectual work of his protégé, Ellis, that provided the organisation’s foundation. [original text “organization’s]”.[4] His intelligence reports about Japan were astute since Ellis observed the Japanese and their methods of war. Major Pete Ellis analysed Japan through the lenses of the symbiotic relationship between the sea and land, and the geopolitical and economic conditions, which would lead Japan to seek a war of attrition against the United States.[5]

A Visionary

As a Marine, Major Ellis penned two articles for the Marine Corps Gazette, a magazine for Marine Corps officers to discuss ideas and analyse past battles. His piece “Liaison in World War” describes how communication broke down with too many liaison officers and how it slowed down the correspondence between command posts and the soldiers on the ground. Ellis describes liaison officers as a hindrance since the commanding officers receive the messages after the liaison delivers the correspondence to a liaison attached to the ground troops. On two occasions, Ellis observed the liaison officers as a distraction. His first example occurred at St. Mihiels. Ellis describes a phone conversation as a waste of time. With the commanding officer and liaison officer at different locations, both men had different observations, and the communication caused confusion between the two officers. At Meuse-Argonne, Ellis watched as a soldier almost knocked down a runner as he sought a liaison officer. By the time the man realised there were zero liaison officers, the runner had delivered the communication. Since the liaisons received the information first, sometimes the Commanding Officers acquired the intelligence or orders too late. Ellis recognised the necessity of liaison officers in technical roles like artillery but wanted the number reduced in other areas, such as infantry. In his experience, there were numerous ineffective liaison officers with only the title. Furthermore, Ellis concluded that the infantry commander should communicate with his officers and the officers to the soldiers and Marines.[6] Regarding liaison officers in 2003, Colonel Nicholas E. Reynolds, USMCR, penned that the Marines operated effectively with fewer liaison officers than required by the Army-Marine manning document.[7]

Ellis recognised the necessity of liaison officers in technical roles like artillery but wanted the number reduced in other areas, such as infantry.

Tackling counterinsurgency (COIN), Ellis discussed in “Bush Brigades” the phases of COIN. In the article, Ellis looks at the difficulty of keeping the support of the civilians, with rogue warriors utilising force to terrorise or bribes to comply. One hundred years later, Ellis’s ideas about COIN remain relevant.[8] In the Afghanistan and Vietnam Wars, the American military needed to have the support of the locals to defeat the enemy. In the Vietnam War, the Marines in I Corps (the provinces of Quang Tri, Thua Thien, Quang Nam, Quang Tin, and Quang Ngai) utilised two programs: CAP (Civilian Action Program) and MEDCAP (Medical Civilian Action Program). Both programs embedded Marines with the Southern Vietnamese. In the CAP program, the Marines lived in the village and worked with the villagers to patrol the area. For the villagers, the MEDCAP provided immunisations, first aid, and general medical care. With both programs, the Marines had made some inroads with the Vietnamese, but Army General Wes Westmoreland had not supported the program, which ultimately stopped the Marines’ progress. Like Vietnam, the American Armed Forces wanted to earn the Afghani tribes’ trust, but the apprehension among the tribes complicated the American effort. While there were some successes; nonetheless, it failed.

At the Naval War College, Commandant Major General William P. Biddle (USMC) invited Ellis to become a student for a short six-week program. Ellis attended in 1911 and stayed on for the year-long program on war planning. While Ellis studied at the Naval War College, Admiral William L. Rodgers of the United States Navy (USN) requested that Ellis extend his time at the college to become an instructor. Ellis stayed on, and he taught the cadets about advanced base warfare. In 1921, the Marine Corps Division of Operations and Training created a pamphlet with Ellis’s Naval War College lectures. The lessons were: “Naval Bases: Locations, Resources, and Security,” “The Denial of Bases,” “The Security of Advanced Bases and Advanced Base Operations,” and “The Advanced Base Force.” The Marine Corps used the pamphlet to train officers on amphibious operations and planning.[9] Besides the Naval War College, Ellis deployed to diverse locations such as Hispaniola, France, and Micronesia, and he had a variety of assignments, for example, Adjutant 4th Marine Brigade, the Executive Officer (XO) 5th Marines, and Marine liaison to France.[10]

Deadly Amphibious Operations

As a result of the disastrous British Gallipoli campaign (1914-1915), the militaries around the globe declared amphibious operations as no longer viable. For Great Britain, the lesson was costly since the British suffered severe casualties for zero gain in territory. After the calamity that was Gallipoli, other militaries analysed the battle, and they viewed amphibious operations as deadly and impossible with the new armaments developed during the Second Industrial Revolution (1870-1914). The nascent weaponry included High Explosive (HE) mortars and more accurate and lethal ammunitions that could travel over longer distances. Furthermore, trench and chemical warfare brought new challenges to the world’s militaries. In response to the horrors of the Great War, new theories developed in the nascent field of air power. One of the prominent air power theorists is Generalissimo Gulio Douhet (1839-1930). Douhet believed that in the next war, air power alone would win the war. In Command of the Air, Douhet penned that by having command of the air, a nation retains its air power and the ability to protect its territory. Furthermore, Douhet stated to win the conflict, a country should strike the enemy’s air bases and population centres. By attacking the civilians, the masses would demand a cease-fire to end the war, and the conflict would conclude.[11] Douhet wanted to increase the size of the air force by decreasing the army and navy, which moved the army and navy into a supporting role.[12]

After the calamity that was Gallipoli, other militaries analysed the battle, and they viewed amphibious operations as deadly and impossible with the new armaments developed during the Second Industrial Revolution.

Another development in the interwar years (1919-1941) was the Washington Naval Conferences (1921-1922). In the Five-Power Treaty, Great Britain, France, Italy, Japan, and the United States agreed to reduce the tonnage of warships, stop building capital ships, and scrap old naval vessels. Signing the Four-Power Treaty, France, Great Britain, Japan, and the United States agreed to communicate any intentions to act in the Far East. The final treaty was the Nine-Power Treaty (Belgium, China, France, Great Britain, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Portugal, and the United States). The signatories had agreed to respect the territory of China, Japan kept control of Manchuria, and China promised to treat each nation fairly in business without any discrimination.[13]

Rising Above the Struggles

As the United States Armed Forces downsized and made adjustments, the Joint Board of Army-Navy started to look ahead to the next war and formulated a series of plans called the Rainbow Plans. Each colour represented a nation. War Plan ORANGE, for instance, represented Japan and covered the United States’ war plan against Japan. At the same time, the Army, Marine Corps, and Navy struggled with shoestring budgets and intra-service rivalry. For instance, the Army’s cavalry and infantry had to fight over the Army’s budget, and the Marine Corps only received their share of the naval funds after the Navy took its expenditures out. Resisting this, the Marine Corps rose above the struggles and developed into an elite amphibious force.

Appointed in 1920, Marine Commandant General John Archer Lejeune began modernising the Marine Corps. As an officer with the American Expeditionary Forces, Lejeune observed the Battle of Belleau Wood (June 06, 1918 – June 24, 1918). He noticed the involved 4th Marine Brigade had not received the proper training or equipment. His beloved Marines had adapted to the German tactics and strategies and would triumph at Belleau Wood; nevertheless, the victory came with terrific casualties as the Germans slaughtered the Marines when they marched into Belleau Woods. After Lejeune’s observations, he made changes to reflect his conviction that the Marines needed to continue education and keep current combat strategies, tactics, and operations up-to-date.

On March 03, 1921, Lejeune penned “Establishing the Advanced Base,” which was Marine Corps Order No. 7. Within the directive, Lejeune instituted two training centres at Marine Barracks, Quantico, VA, and at Marine Barracks, San Diego, CA. The First and Second were composed of an artillery regiment, an infantry brigade, and a technical regiment. The 1st and 2nd, Lejeune’s new name for the troops receiving schooling at the two billets, had training in artillery, fire control, submarine mines, searchlights, signals, and engineering.[14] With Major Ellis’s amphibious operational theory, Lejeune began the transformation of the Corps.

As the Joint Army-Navy Board continued planning for war, Lejeune discovered an opportunity for the Marines to put its imprint on War Plan ORANGE. Since Ellis had written about Japan as a world power and a threat, Lejeune deployed his trusted friend Ellis on a fact-finding mission in the Far East. After Ellis returned, he penned “Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia,” also known as Operation Plan 712. He included a brief description of Japan in the areas of readiness for war and experience in offensive ship-to-shore operations. General Lejeune approved and endorsed Ellis’s Operation Plan 712 in 1921.[15]

Operation Plan 712

As a remarkable visionary, Ellis’s “Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia,” Operation Plan 712, is a groundbreaking paper. Ellis’s text had a significant influence on the American Armed Forces. Since Operation Plan 712 included the Corps’ part of War Plan Orange, “Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia” had the Marines’ amphibious route mapped out for World War II, which the Marines followed except for adding the Gilbert Islands. The Battle of Tarawa, moreover, was the first long-distance amphibious operation from an air carrier, and the Marines proved Ellis’s amphibious theory.[16] Since Operations Plan 12 influenced the Corps’ writing the Tentative Landing Manual in 1933, he also affected the Navy, who penned the Landing Operations FTP 167 using the Corps’ amphibious manual. Likewise, the Army built upon the Tentative Landing Manual and FTP 167 to write the War Department’s FM-35 War Department Field Manual: Landing Operations on Hostile Shore. During World War II, the Army subsequently had the largest littoral amphibious operation at Normandy in France on June 6, 1944. American soldiers launched the amphibious assaults from mulberries in the littorals of Omaha Beach.[17] By the Pacific Theater’s conclusion, the Marine Corps developed into an elite amphibious force as they continually refined the amphibious doctrine to meet its needs to defeat the Japanese foes. With Japan’s surrender, the Marine Corps redefined its role as America’s elite amphibious force for generations.

Since Operation Plan 712 included the Corps’ part of War Plan Orange, “Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia” had the Marines’ amphibious route mapped out for World War II, which the Marines followed except for adding the Gilbert Islands.

A complete plan, “Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia,” describes the two main types of terrain: coral and volcanic.[18] Ellis, furthermore, mentions the difficulties a joint task force may confront. A great example is the communication breakdown at the Battle of Tarawa, which comprised the atolls of Makin, Apamama, and Tarawa. The commander of V Amphibious Force, Admiral Turner, had failed to notify Admiral Hill, commander of the Southern Task Force, of the American submarine in his zone. Admiral Hill ordered the attack on the Nautilus. The Nautilus carried a small contingent of Marines heading to Apamama. Fortunately for the Nautilus, one hit the conning tower, and the other was a dud. The Nautilus delivered the contingent of Marines, and the Marines seized Apamama.[19] In a coral atoll, for example, the only decent landing field is on the beach. Another issue is the coral reefs in the lagoons. At Tarawa, the 2nd Marine Division’s amphibious plan had counted on the tide leaving enough water to traverse the reef, but the tide ebbed, which resulted in the Marines crawling over the reef. The volcanic atolls had deeper lagoons, and it nevertheless had its problems. With mangroves on the shoreline of Papa New Guinea, the mangroves hindered the Marines’ progress moving inland. Discussing the advantages too, for instance, Ellis mentions that the volcanic islands have good drinkable water. Other areas looked at include the population demographics and the economic resources, such as agriculture. Ellis provides a complete geographic picture of the situations on the islands, as he desires to give the troops a precursor to INTEL preparation of the operational area (IPOE) before they deploy to the Far East.[20]

“Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia” has several essential concepts as the ideas prevail through the years. Remaining crucial to amphibious operations is flexibility and mobility. As the Navy delivers the troops to the embarkation zone, it may face ever-changing tides. The Navy may have hidden obstacles in the sea, so the Marines and Soldiers must embark earlier than planned. Consequently, the troops have to have the strength and endurance to overcome any obstacles like coral reefs and tree roots in the lagoons they may confront. It is vital to have troops who arrive swiftly and stealthily. As the landing troops have no capability for offence, they must advance rapidly to the shore and the terrain, where the units may start an offensive campaign. The embarkation team’s only defence is the Naval Gun Support and the aeroplanes as they cover them.

Remaining crucial to amphibious operations is flexibility and mobility. As the Navy delivers the troops to the embarkation zone, it may face ever-changing tides.

Unity of command is another essential component. With clearly defined roles, the Navy and Marine Corps need to work together. Foremost to the success of unity of command is communication, and an effective means is to divide responsibility between the two services by having a liaison on the command staff. The other central idea is to have one commander in charge, and the Navy is in command on the sea while the Marines take over when on land. By listening to each other, the command structure permits the best-case scenario for the operations with its strategies and tactics. An extension of the unity of command is excellent communication. For the troops spread out over a large landing zone, consistent communications permit the joint task force to operate without any redundancy and, even more significantly, prevent friendly-fire attacks. Another vital notion, the joint task force should only take the equipment required for the mission since the amphibious troops carry all the paraphernalia with them when embarking on an amphibious operation.[21]

Ellis had moreover composed general principles of defence of the advanced bases. A primary requirement is to have the appropriate force ratio to destroy the foe’s maritime and air forces. Another guideline is to defend the anchorage and the port facilities from the enemies’ devastation. In combat, the Navy, Army, and Marines supply the combined task force to ensure familiarity with weaponry and armaments. For fewer days of instruction and to simplify training and supplying, the joint task force should utilise only the equipment and supplies provided by the Quartermaster General.[22] Another vital section of the “Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia” was the summary and description of strategy, tactics, materials, personnel, and the organisation. Ellis presented a summation of Operation Plan 712, and in the strategy subsection, he had included sub-objectives, such as a reduction of a base as the fleet required a port for the convoy. Major Ellis also covered the tactic and emphasised close, rapid fighting combined with operations carried out with surprise and swiftness. To illustrate the proposed task establishment, Ellis created a chart. The summary exhibited a straightforward brief of Ellis’s amphibious operational theory.[23]

Ellis presented a summation of Operation Plan 712, and in the strategy subsection, he had included sub-objectives, such as a reduction of a base as the fleet required a port for the convoy.

Ship-to-Shore

Amphibious operations have advantages and disadvantages. One significant benefit occurs when the landing force nears a landmass, as the amphibious operation permits a vast array of lines of approach. The amphibious mission presents the opportunity to use a feint to trick the foes. It, moreover, assists in concealing the objective while allowing the joint task force to retain a reserve fleet. The last advantage is that it produces an opportunity to capitalise on the initial success of the amphibious operation. For the disadvantages, they are: missions take a longer time to launch, extremely little intelligence at first, resupply is a challenge, support is only as good as the communication and cooperation among the troops, and the naval guns are the only support for the Marines as they embark to the shore.[24]

Ellis, unfortunately, would not live to see the fruition of his life’s work. Yet, Major Pete Ellis had an advocate of amphibious operations with General Lejeune, who took Ellis’s “Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia,” and he had his Marines participate in the Civil War exhibitions. The Marines would reenact the Civil War battle first and then illustrate how the combat would appear as an amphibious assault. From December 1923 to February 1924, the Marines participated in fleet exercises (FLEX). The FLEXs revealed problems like communication and transportation. In the spring of 1925, General Lejeune requested the opportunity to have his Marines prove amphibious operations still had a place in the United States operational plans by planning and executing an amphibious landing. The Marines ran the smoothest run exercise, and nevertheless, it still had a problem with the deficiency of adequate landing craft.[25] Scarcity in the development of amphibious landing craft remained until World War II began in Europe.

Still, the Marine Corps made some headway in building an amphibious force. With the Joint Board of Army and Navy (FTP155) new directive issued in 1927, a change occurred for the United States Marines. It stated the “Marine forces-Marines organised as landing forces perform the same function as above stated for the Army, whether operating with the Navy alone or in conjunction with Army and Navy [original text “organized”].[26] The document created a new avenue for the Marines as a landing force. The FMF (Fleet Marine Force) would have dual operational control depending on the location of the Marines. The Fleet Commander, for instance, retained mission control when the Marines had engaged in combat or fleet exercises at sea or in port, and the Marines’ commander had command once the Marines reached land.[27]

The United States Marines determined the best method of developing a manual to teach the basis of amphibious operational doctrine. In 1933, the Marines closed down all the classes to create its textbook under the leadership of Colonel Ellis B. Miller. They analysed the Gallipoli disaster besides Operation Plan 712. With Colonel Miller, the students developed The Tentative Manual for Landing Operations. With a few adaptations, The Tentative Landing Operational Manual became the foundation for the amphibious warfare manual.[28]

In 1933, the Marines closed down all the classes to create its textbook under the leadership of Colonel Ellis B. Miller. They analysed the Gallipoli disaster besides Operation Plan 712.

In 1931, the Marines recognised the necessity of acquiring ship-to-shore vessels to transport the Marines to the shore. The Marines bypassed the bureaucracy to attain the Higgins boat designed by Andrew Jackson Higgins. He reformulated the Higgins boat with armour for the Marines. In addition, the Marines noticed Roebling’s Alligator as the Alligator could handle moving on land and in rivers. The Marines found the maker of the amtrac or LVT (Landing Vehicle, Tracked), which became a staple of long-distance amphibious operations.[29]

Marine Major General Holland M. Smith and the Marines completed the last step by seizing the amphibious doctrine and planning when they put into action the concepts of amphibious doctrine that Ellis had penned twenty years before. For the Corps, the Pacific Theater of World War II became its amphibious proving ground. Holland Smith’s Marines would solve the issues as they battled on the islands of Guadalcanal and Tarawa. By the time Operation NEPTUNE happened on June 06, 1944, the joint task forces in the Pacific had resolved the problems of amphibious operations, which had slowed down the amphibious missions.[30] As the largest amphibious assault, Operation NEPTUNE became the turning point of the European war for the Allies. World War II assured the role of amphibious operations as part of the American Armed Force’s future combat operations. Ellis’s Operation Plan 712 was the basis for the amphibious operations of World War II and helped the Allies to win the war in the Pacific Theater.

Launched from the Sea: An Amphibious Military Operation

The conclusion of World War II was not the end but just the beginning of modern American amphibious operations. Amphibious operations have occurred in Afghanistan, Iraq, Korea, Pakistan, and Vietnam, and they are still a part of the American military. For the Air Force, Army, Coast Guard, Marines, and Navy, the Joint Chiefs of Staff published Joint Publication 3-02 Amphibious Operations in January 2019 and recertified in 2021,[31] and the JCS defined amphibious operations as, “… a military operation launched from the sea by an amphibious force (AF) to conduct landing force (LF) operations within the littorals. The littorals include those land areas (and their adjacent sea and associated air space) that are predominantly susceptible to engagement and influence from the sea and may reach far inland.”[32] In today’s geopolitical environment, amphibious operations will remain critical, particularly in the Pacific.

In today’s geopolitical environment, amphibious operations will remain critical, particularly in the Pacific.

Major Earl H. “Pete” Ellis is a visionary and theorist. B. A. Friedman states that Ellis is the first theorist of amphibious operations and has remained the only amphibious theoretician.[33] “Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia” is a document that students should still investigate and analyse as it endures as a revolutionary text. Amphibious operational theory facilitated the formation of the modern Marine Corps. Utilising Ellis’s “Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia” and the Marine Corps’s amphibious doctrine, the Navy and Army created its amphibious precepts. In addition, Ellis planted the seeds for future ideas of the American military, such as combined forces, COIN, and A2/D2.[34] Major Pete Ellis’ “Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia” remains relevant to the United States Military in the 21st Century, particularly the Marines, who still stand as the premier amphibious force. Even though Ellis penned the text in 1921, Plan 712 has continuously impacted modern amphibious doctrine throughout the years. As B. A. Friedman wrote, “In a world in which most developed militaries are expanding their amphibious force projection capabilities, it is right to look back at one of the greatest innovators the United States military has ever produced.”[35]

Lynne Marie Marx graduated from American Military University in 2021 with a MA in military history. Mrs Marx has had her work on the Battle of Chosin Reservoir published in The Saber and Scroll and The United States Military History Review. Her interests are the United States Marine Corps history, amphibious operations, and the period of the Great War through the Korean War. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone.

[1] Allan R. Millett, Semper Fidelis, rev. and ex. ed. (New York: Macmillan Pub. Co., 1991), 287.

[2] Earl H. Ellis, “Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia,”Quantico, VA: Intelligence Section Division of Operations and Training U.S. Marine Corps, 1921, Historical Amphibious File, Box 6, Folder 1, Marine History Division and Archives, Quantico, VA.

[3] As the commander of V Amphibious Force, General Holland Smith directed the amphibious forces in the Pacific Theater, and he was there during the first long-distance amphibious operation, the Battle of Tarawa. He also assisted in the development of the amphibious program.

[4] B.A. Friedman, ed, 21st Century Ellis: Operational Art and Strategic Prophecy for the Modern Era (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2010), 9.

[5] Ibid., 71-74; Ibid., 144.

[6] E. H. Ellis, “Liaison in World War,” Marine Corps Gazette (pre-1994) 5, no.2 (June 1920): 135-141, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy1.apus.edu/docview/206293890?accountid=8289.

[7] Colonel Nicholas E. Reynolds, USMCR, U.S. Marines In Iraq, 2003: Basrah, Baghdad And Beyond: U.S. Marines in the Global War on Terrorism [Illustrated Edition] (San Francisco: Tannenberg Publishing, 2014), 57, ProQuest Ebook Central.

[8] Friedman, 21st Century Ellis, 49, 75, 36, and 16; E. H. Ellis, “Bush Brigade,” Marine Corps Gazette (pre-1994) 6, no. 1 (March 1921): 1-15, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy1.apus.edu/docview/206288008?accountid=8289.

[9] Dirk Anthony Ballendorf and Merrill L. Bartlett, Pete Ellis: An Amphibious Warfare Prophet, 1880-1923 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997),53-54; Friedman, 21st Century Ellis: Operational Art and Strategic Prophecy for the Modern Era, 45; Earl H. Ellis, “Naval Bases: Location, Resources, Denial of Bases, Security of Advanced Bases,” (Quantico, VA: United States. Marine Corps. Division of Operations and Training, 1921),http://edocs.nps.edu/2012/December/1921-Ellis%20Paper%20on%20Naval%20Bases.pdf.

[10] Ballendorf and Bartlett, Pete Ellis: An Amphibious Warfare Prophet, 1880-1923, 76-102.

[11] Giulio Douhet, The Command of the Air, trans by Dino Ferrari, (Auckland, NZ: Pickle Partner Publishing, 2014), 1,24, 29, 58. Kindle.

[12] Ibid., 29, 309.

[13] The Washington Naval Conference, 1921-1922, Office of the Historian, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/naval-conference.

[14] John A. Lejeune, “Establishing the Advanced Base Force” Marine Corps Order No. 7 (Series 1921) March 3, 1921, Historical Documents, Orders, And Speeches, Marine Corps University, Marine Corps History Division Quantico, VA, https://www.usmcu.edu/Research/Marine-Corps-History-Division/Frequently-Requested-Topics/Historical-Documents-Orders-and-Speeches/Establishing-the-Advanced-Base-Force/.

[15] Millett, Allan R., Peter Maslowski, and William B. Feis, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States from 1607-2012, 3rd ed.,(New York: Free Press, 2012), 353-354; Ellis, “Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia, 1, 12.

[16] The Battle of Tarawa was the laboratory to prove amphibious operations were viable. On Betio, the island in the Tarawa atoll, the Marines fought a fierce enemy, who had made Betio a defensive stronghold. It took the Marines 72 hours to seize Tarawa from the Japanese. For more information see Across the Reef: The Marine Assault of Tarawa by Joseph H. Alexander, https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/Across%20the%20Reef%20-%20The%20Marine%20Assault%20of%20Tarawa%20%20PCN%2019000312000_1.pdf.

[17] Operation NEPTUNE was the naval component and phase 1 of Operation OVERLORD; “Operation Neptune: The U.S. Navy on D-Day, 6 June 1944” Naval History and Heritage Command, May 28, 2019, https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/1944/overlord/operation-neptune.html; The mulberry was a manmade harbor; Jon T. Hoffman “The Legacy and Lessons of Operation OVERLORD,” Marine Corps Gazette 78, no. 6 (June 1994): 68-72. http://ezproxy.apus.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Ftrade-journals%2Flegacy-lessons-operation-overlord%2Fdocview%2F221460354%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D8289.

[18] Ellis, “Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia,” 4-6.

[19] Joseph H. Alexander, Utmost Savagery: The Three Days of Tarawa (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1995), 219, 221.

[20] Ibid., 4-11.

[21] Ibid., 43,74.

[22] Ibid., 1-8

[23] Ibid., 2-7

[24] Joint Board of the Army and Navy, Joint Action of the Army and the Navy FTP 155, (1927; repr., Washington, DC: United States Government Press, 1935), 74. https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/ref/Joint/index.html.

[25] Millet, Semper Fidelis, 323-329; Ballendorf, An Amphibious Warfare Prophet 1880-1923, 160; Frank O. Hough, Verle E. Ludwig, and Henry I. Shaw Jr., “Evolution of Modern Amphibious Warfare, 1920-1941,” In: Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal History Vol 1 U. S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, (Washington, DC: Historical Branch G-3 Division Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1958), 11. https://ibilio.org/hyperwar/USMC/I/USMC1-1-2.html.

[26] Joint Board of Army and Navy, FTP155, 13; Hough, “Evolution of Modern Warfare,” 14.

[27] Hough, “Evolution of Modern Amphibious Warfare,” 13.

[28] Ibid., 14.

[29] Millett, Semper Fidelis, 340-341; Joseph H. Alexander H., “Hit the Beach,” Military History 25, no.4 (September/October 2008): 35, https://search-proquest-com.ezpoxy1.apus.edu/docview/212674419?accountid=8289.

[30] See note 16.

[31] Joint Chief of Staffs, Joint Publication 3-02 Amphibious Operations (Washington, DC: Joint Chiefs of Staff Publication, 2019), https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/jp3_02.pdf.

[32] Ibid., xi,

[33] Friedman, 21st Century Ellis, 11.

[34] COIN (counterinsurgency) and A2/D2 (area access/area denial).

[35] Friedman, 21st Century Ellis, 82; Ibid., 145.