Abstract: Russia is the only non-NATO country among all Arctic neighbouring nations. It is uniquely placed, both in terms of the capacities it possesses and the challenges it faces while operating in the Arctic. The US, unlike Russia in the Arctic region, enjoys the support of the majority of the Arctic states. However, possessing the largest territorial area, Russia owns a huge territory in the Arctic. The Northern Sea Route (NSR) runs along the Russian Arctic coast. The US claims the NSR is an international waterway, whereas Russia claims the waters are historically its own. The Arctic represents an important chapter of the US-Russia relationship from the beginning to current times.

Problem statement: How to understand Russia’s former and potential future role in the Arctic?

Bottom-line-up-front: Despite the Russian invasion of Ukraine causing several deadlocks and placing countries at diplomatic loggerheads, dissolving the Arctic Council seems unthinkable. However, having no neutral members may undermine the council’s credibility, yet the Arctic Council has been successful in resolving any dispute previously. The US is aware that any organisation in the Arctic region with NATO members may encourage other sub-Arctic states to interfere in Arctic politics and cause more dangers in the future.

So what?: According to Russia, one reason for the crisis was the reaction to expanding the membership of NATO. Moreover, Russia may have also not understood that the world is now multipolar. Russia must avoid retaining the Cold War’s bitterness and continue scientific research. It must remember that the mandate of the Arctic Council in which security issues were eliminated by noting that their inclusion could sour the relationship between NATO and Russia. The Arctic Council mandate was itself an assurance of maintaining collaboration on the Arctic Environmental issue under all the conditions.

Source: shutterstock.com/Peter Hermes Furian

The Arctic: A Geopolitical Hotspot

The Arctic is the world’s smallest and shallowest ocean but is surrounded by some of the largest, most dominant global players. Of the Arctic nations, Russia, Canada, and the US are unique by virtue of having continental shelves in three oceans: the Pacific, the Arctic, and the Atlantic. Initiating any cooperative treaty amongst the Arctic states during the Cold War seemed almost impossible. Especially because it was already an arena ripe with discontent ever since the Alaska Purchase of 1867, this agreement which ceded Alaska to the US, has remained a cause for disagreement between the US and Russia: it led to friction regarding the division of maritime boundaries in the Bering Sea.[1]

Of the Arctic nations, Russia, Canada, and the US are unique by virtue of having continental shelves in three oceans: the Pacific, the Arctic, and the Atlantic.

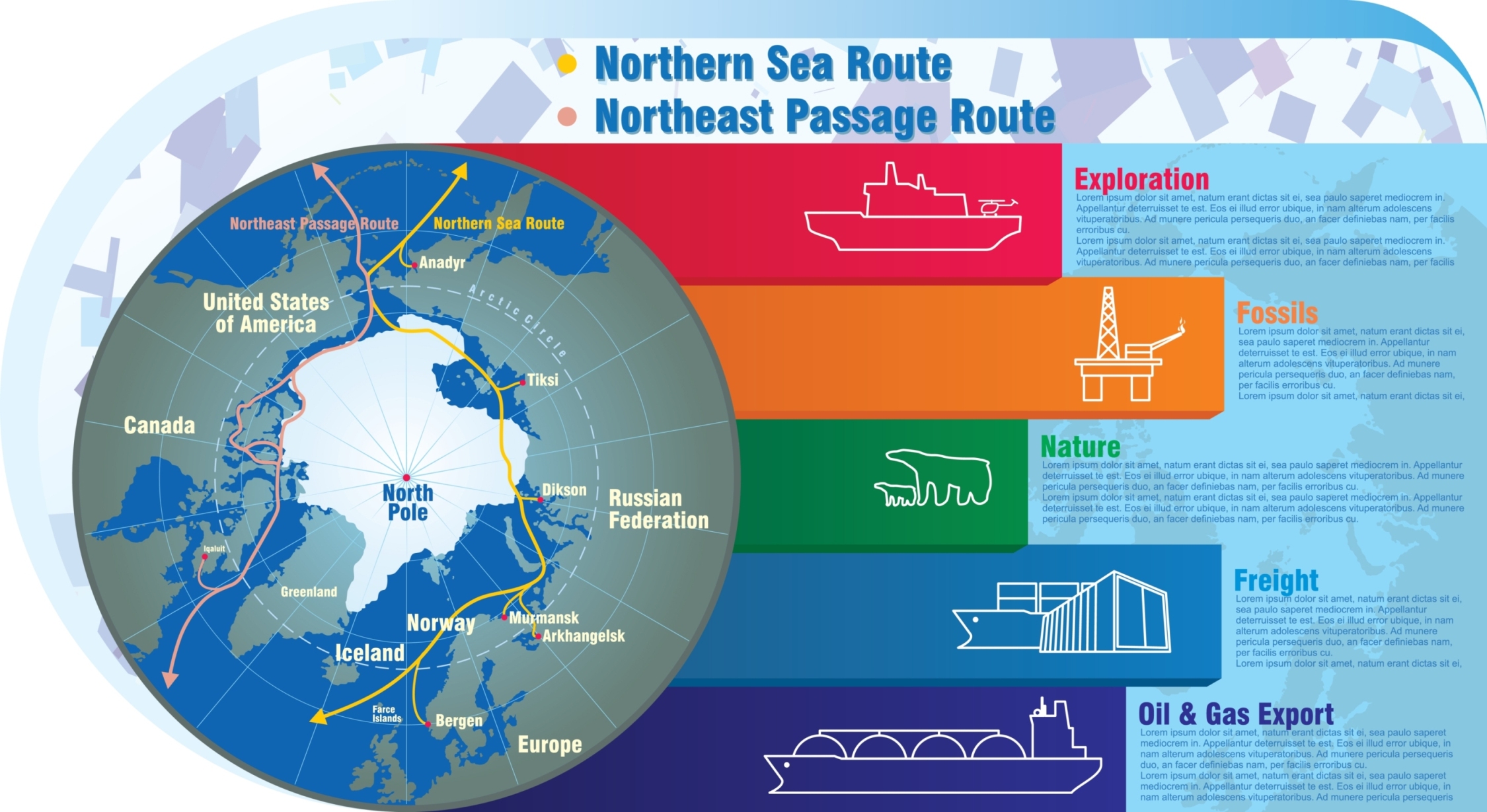

The question of sovereignty over the NSR or Northeast Passage (NEP) is another reason for friction between the US and Russia. The US and its European allies claim the NSR as an international strait.[2] However, Russia differs, claiming historical and comprehensive Russian authority over these waters. The US also opposes its closest ally, Canada, to counter the Russian position, arguing that the waters in the Northwest Passage (NWP) are historically theirs.[3] The US maintains that the waters in the NWP running through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago (CAA) are international. Russia and Canada own territories in the Arctic through which the potential sea lanes may pass. Here too, the challenges are similar, with the main being the issue of sovereignty over the passages. This has promoted Russia and Canada to maintain corresponding positions against the US. Canada is also looking for solace in Russia on matters of sovereignty. In such a situation, Russia finds it prudent to support Canada against the US. Another irritant between the US and Russia is the US’s refusal to endorse the United Nations Convention on the Law of Seas III, 1982(UNCLOS III).[4]

The Alaska Purchase of 1867 (or the Treaty of Cession)

The first instance of Russian-American interaction in the Pacific featuring “high politics” — strategic interests involving the States — was the Alaska Purchase of 1867.[5] The Alaska Purchase involved long-term Russian geopolitical interests. Its first aim was to limit the influence of the UK, then the imperial power controlling Canada, and maintain a stable relationship with the US. This relationship provided Russia with the leverage to challenge the British position. Under Tsar Alexander II, Russia experienced an economic downturn. It was forced to sell Alaska, yet choosing the US as the buyer was a Russian objective as it would create difficulties for its traditional enemy, the UK.[6] The Alaska Purchase became crucial in shaping geopolitics in the Arctic. It added several dimensions to it by making the Arctic a superpower battleground with the emergence of the bipolar world order. Noting the differences between the US and Canada, it became the catalyst for Russia-Canada relations in the Arctic, which, subsequently, often challenged the US attitude in the Arctic.

US-Russia Hostility During the Cold War

The Bering Sea Dispute

The Purchase Agreement defined a marine boundary between Russia and the newly acquired US territory. The deal of 1867 determined two geographical lines: one in the Bering Sea and the second in the Arctic Ocean. These lines delimited American and Russian territories. However, in the case of the Bering Sea, the agreement did not only apply to maritime territories. It was not intended to delimit the Exclusive Economic zone (EEZ) — a concept that did not exist when the treaty was created. When UNCLOS III was adopted, the 1867 Treaty line became the most contentious maritime boundary in the world because of the indistinct language in the purchase agreement between Russia and the US. Thus, it failed to define the type of line, map projection, and horizontal datum used to illustrate this boundary.[7] Neither of the two countries in the dispute possesses original or other authenticated maps used during the negotiations to resolve the issue. When the US and the Soviet Union implemented 200-nautical mile EEZs in 1977, they exchanged diplomatic notes indicating their intent “to respect the line outlined in the 1867 Convention” as the limit for each country’s fisheries jurisdiction where the two hundred nautical mile boundaries overlapped. Though this dispute was supposed to be resolved in a 1990 document known as the “Baker-Shevardnadze Agreement” between the United States and the USSR, today, the situation remains unclear. Though both the countries made compromises, the US still controls a far more significant amount of area in the Bering Sea than the new agreement proposed, based on the equidistant line principle typically used in international boundary disputes. The US quickly ratified the 1990 Agreement; however, the USSR did not.[8]

Dispute Over the Northern Sea Route

Russia claims sovereignty over the NEP, which has become navigable following the melting of the ice in the Arctic Ocean. Still, the US opposes it by claiming these waters are international.[9] Opposing the Russian position in August 1967, the US Coast Guard icebreakers, Edisto and Eastwind, traversed the NEP via the Vilkitsky Strait, less than twenty-four nautical miles wide. On August 28, 1967, the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs advised the American Embassy in Moscow that the passage of certain US ships through the Vilkitsky Straits “would be a violation of Soviet frontiers”.[10] Though at that time, the limit of the territorial waters was only three nautical miles, Russia was not in agreement and adhered to the twelve nautical miles territorial sea limitation. Against the American argument of “innocent passage” being applicable in any condition for the ships in question, Russia defended itself by saying, “the coastal state may, however, suspend temporarily in specified areas of its territorial seas the innocent passage of foreign ships if such suspension is essential for the protection of its security”.[11] Despite this severe disbarment as was visible globally, and when Russia violated the rule of three nautical miles’ territorial sea, the US did not even protest. This incident reveals the American stance of supporting another power implicitly yet showcasing the disagreement globally.

Against the American argument of “innocent passage” being applicable in any condition for the ships in question, Russia defended itself by saying, “the coastal state may, however, suspend temporarily in specified areas of its territorial seas the innocent passage of foreign ships if such suspension is essential for the protection of its security”.

Russia has the largest territory in the Arctic (1,75,000 km in length) and the largest Arctic population. The area is rich in hydrocarbons and mineral deposits, like diamonds and gold. Hydrocarbons have provided significant leverage for Russian foreign influence.[12]

The US-Russian rivalry has remained quite different in the Arctic region. Unlike in other parts of the world, both countries have never been involved in wars and military conflicts against each other, despite undoubtedly having massive military build-ups in the Arctic. Though the US as a NATO leader, enjoys a majority in the High North as three other Arctic rimming nations (Canada, Norway, and Denmark) are NATO members, peaceful neighbourly relationships exist due to its military capacity and huge territory Russia maintains a strong position in the Arctic.

Until the US ratifies the UNCLOS, there remains the possibility of worsening disputes with Russia over borders in Arctic seas and the continental shelf boundary. The US already opposes Russia’s attempts to expand the zone of its shelf to the Lomonosov and Mendeleev Ridges. Russia’s application to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (UNCLCS) was rejected in 2001 due to US State Department pressure (2014).[13]

Diplomacy for Power Balancing

Canada has the second largest Arctic territory and, together with the US, they are the most important trading partners; they also work together militarily: both multilaterally through the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) and bilaterally through the North American Aerospace Defence Command (NORAD). Nevertheless, Canada’s claim to sovereignty in the Arctic has proven to be a major irritant in this bilateral relationship. However, this difference worked as an ice breaker in the Russia-Canada relationship; both feel they have extensive jurisdictions and sovereign rights in the Arctic and see the Arctic as their frontier of destiny.[14] The two nations — Canada and Russia — feel entitled to a vast Arctic presence as both countries dominate the Arctic coastline and are often referred to as the ‘king/s of the Arctic’.[15] However, Canada’s dependency on the US for security is a limitation that obstructs its relationship with Russia. This interdependency between the US and Canada emerged during World War II when it was felt that the US could not defend itself effectively against a major attack based on Canadian soil. To the Canadians, it was obvious that their meagre resources in terms of population and military equipment were incapable of protecting the vast reaches of their national domain. Defence cooperation was as inevitable as it was imperative.[16] Canada calls the US its premier partner in the Arctic; the US refers to its unique and enduring partnership with Canada and their mutual interests in the region.[17]

The two nations — Canada and Russia — feel entitled to a vast Arctic presence as both countries dominate the Arctic coastline and are often referred to as the ‘king/s of the Arctic’.

The US has supported Canada’s defence in many respects because it sees the neighbour as an invaluable ally. This collaboration was also meant to limit the NATO presence in the Arctic. Assigning this task to NATO would mean inviting the interference of the other European nations in Arctic matters.

However, there are disagreements between Canada and the US over the status of the NWP in which there is scope for Russia to side with Canada outside defence and security matters. This inclination of Russian policy toward Canada became apparent when the Canadian Government enacted the Arctic Water Pollution Prevention Act (AWPPA) in 1970, after the voyage of the SS Manhattan in 1969. After this, several events revealed that these two Arctic ‘kings’ were coming closer—although not always against the US.

The end of the Cold War and the melting of the Arctic ice has caused a growth of the Russian voice about the Arctic. However, a common interest in sovereignty remained the only factor cementing this relationship. “Agreement between the Government of Canada and the Government of the Russian Federation on Cooperation in the Arctic and the North”, signed by Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and Russian President Boris Yeltsin in 1992, tried to overcome the barriers of West and East camp hostility and tried to develop bonding as good neighbours.[18] The priority areas of cooperation were:

Economic development, including small business; socio-economic and cultural problems; relations and contacts between aboriginal peoples; land use planning and management; construction in the Arctic and northern regions; geology in the Arctic and northern regions; the effects and transport of contaminants; the development of renewable and non-renewable resources; education and professional training; policy and legislation relating to the administration of the Arctic and north territories; hydrometeorological research and monitoring; fisheries; science and technology; Arctic air, land, and marine technology; medical services and healthcare delivery; tourism; transportation; and such other areas as may be mutually agreed (Government of Canada and Russia, 1992).[19]

Again in 2000, the “Northern dimension of Canada’s foreign policy” set four objectives for circumpolar engagement. One of the policy paper’s key priorities was working with Russia to address northern challenges, such as cleaning up Cold War environmental legacies and funding Russian indigenous peoples’ participation in the Arctic Council. “Perhaps more than any other country”, the policy paper declared, “Canada is uniquely positioned to build a strategic partnership with Russia for the development of the Arctic”.[20]

One of the policy paper’s key priorities was working with Russia to address northern challenges, such as cleaning up Cold War environmental legacies and funding Russian indigenous peoples’ participation in the Arctic Council.

The words reflect that the Canada-Russia ties are not on defence or military issues which can disturb the defence relations between the US and Canada. Despite the possibility that Russia could maintain good relations with its Arctic neighbours, Russia hardly looked serious in its endeavour. Yet, Mikail Gorbachev’s Murmansk speech was welcomed and significantly changed the Arctic region’s fate.

The Murmansk Speech and Creation of the Arctic Council

The landmark Murmansk Speech was the most remarkable event in changing the face of Arctic politics. Mikhail Gorbachev delivered the speech in Murmansk in October 1987. This speech has been viewed as a symbolic turning point in the pattern of international relations in the circumpolar North due to the weakening of the Soviet economy. In 1987, when the Soviet economy was experiencing a slump, the Russian President again took the lead role in changing the geopolitical scenario in the Arctic. He announced that the Arctic should be made a rule-based region, called for international cooperation to create an organisation that made the indigenous community partners, and assured everyone that Russia would take the initiative.[21]

In his speech, Gorbachev set forth a multidimensional programme of cooperative initiatives in the North, including the creation of a nuclear-free zone; restrictions on manual interventions causing damage to the Arctic environment in the North; peaceful cooperation in the development of Arctic resources; the coordination in scientific research; a partnership in protecting the Arctic environment; the opening of the NSR; and the recognition of the indigenous peoples. Gorbachev also called those interested in the region to join forces to form the Arctic into “a genuine zone of peace and fruitful cooperation”.

The Soviet proposals for increased cooperation in scientific research and resource extraction in the Far North were motivated by its interests in the resources of the Arctic. To be able to extract resources, Russia required Western technology and know-how. The Soviets hoped to gain from Western expertise and experience in exploiting offshore oil and gas cost-effectively.[22] The Arctic countries welcomed the initiation of bilateral or multilateral cooperation in the Arctic region.

To be able to extract resources, Russia required Western technology and know-how. The Soviets hoped to gain from Western expertise and experience in exploiting offshore oil and gas cost-effectively.

The Canadian External Affairs Minister, Joe Clark, welcomed Gorbachev’s proposal for promoting bilateral and multilateral cooperation in the Arctic in non-military areas, like energy, science, and the environment, creating an Arctic Sciences Council, and developing cultural links among the indigenous peoples of the North. However, a series of questions and counter-questions from the Canadian side emerged during this speech, and the Soviet authorities gave several clarifications. Thus, the Murmansk speech ultimately paved the way for bilateral and multilateral negotiation cooperation in non-military fields in the Arctic.[23]

Source: shutterstock.com/piscari

Russia and the Arctic Council

Mikhail Gorbachev’s initiative could not mitigate the East-West gap completely, yet it represented the first step by an Arctic State towards a cooperative arrangement in the Arctic. Occasional tensions between Russia and NATO remained a matter of grave concern. There was a fear that the Arctic Council might be caught up in the crisis that followed Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March 2014. Indeed, a rift was created in the Canada-Russia relationship. Canada boycotted a meeting of a task force on black carbon in response to “Russia’s illegal occupation”. However, Canada stated that it would “continue to support the important work of the Arctic Council”. But, after this, the subsequent meetings were attended by all the eight member states, and cooperation on practical, shared challenges continued. In April 2015, Russia’s Minister of Natural Resources and Environment, Sergei Donskoi, joined the Iqaluit Declaration.[24] In doing so, Russia agreed to adopt the US programme for its two-year Chairmanship. Although Canada was against Russia’s actions in Ukraine during the Iqaluit ministerial summit, the practical work of the AC continued. Russia supported the creation of the task force. In this meeting, the members unanimously agreed to establish a task force named ‘Task Force on Arctic Marine Cooperation’ (TFAMC), with a mandate to prepare a mechanism to foster cooperation in marine-related issues against emerging future challenges.[25] Another limitation of the Arctic Council is that it has no mechanism to resolve disputes even within the Arctic region.

The Ilulissat Declaration, issued in May 2008, became a significant locus of difference in the Arctic Council.[26] In the Declaration, Canada, Denmark (Greenland), Norway, Russia, and the US (A-5 nations) proclaimed that:

By virtue of their sovereignty, sovereign rights, and jurisdiction in large areas of the Arctic Ocean, the five coastal states are in a unique position to address these possibilities and challenges. In this regard, we recall that an extensive international legal framework applies to the Arctic Ocean, as discussed between our representatives at the meeting in Oslo, on 15 and 16 October 2007, at the level of senior officials. Notably, the law of the sea provides for important rights and obligations concerning the delineation of the outer limits of the continental shelf, the protection of the marine environment, including ice-covered areas, freedom of navigation, marine scientific research, and other uses of the sea. We remain committed to this legal framework and to the orderly settlement of any possible overlapping claims.

The Ilulissat Declaration, issued in May 2008, became a significant locus of difference in the Arctic Council.

The A5 unanimously affirmed that UNCLOS III is efficient in governing maritime issues in the Arctic; therefore, no new treaty is required to govern the Arctic Ocean.

Russian Invasion of Ukraine

The Russian invasion of Ukraine set back scientific research and environmental collaboration in February 2022. This happened at the most inopportune time in the history of the Far North and the Arctic Council. All the positive indicators of the past—that the Arctic Council has successfully represented cooperation on the environmental and climate change between East and West after coming into existence in 1996—were disproven. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine abruptly ruined the Arctic Council’s ability to resist geopolitical storms. This spirit of cooperation has been wiped out, and there is a possibility that it can affect the functioning of the Arctic Council in the future.

On March 3, 2022, less than two months after the Arctic Council was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, seven permanent members of the council (excluding Russia) took an unprecedented step by declaring they would be “pausing participation in all meetings of the Arctic Council and its subsidiary bodies”. The forum had previously navigated diplomatic disagreements among member states, including over the Iraq War in 2003, the Georgian War in 2008, and the annexation of Crimea in 2014. Moreover, the disagreement over the invasion of Ukraine was irreconcilable. Not only has this invasion changed the future of Arctic relations, but it has also (temporarily) ended Russia’s participation in one of its few remaining soft power venues capable of meaningful international coordination.[27]

On March 3, 2022, less than two months after the Arctic Council was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, seven permanent members of the council took an unprecedented step by declaring they would be “pausing participation in all meetings of the Arctic Council and its subsidiary bodies”.

Apart from being the most significant Arctic power, Russia (Canada has the most extensive coastline in the Arctic Ocean) also holds the most important share of mining resources and population in the Arctic. The invasion of Ukraine questions the successful functioning of an international organisation like the Arctic Council.

Just as Russia decided to attack Ukraine, a global consortium of permafrost scientists was poised to embark on a multi-year, Arctic-wide monitoring effort that would have helped provide crucial data on how the region is warming. The international uproar and financial sanctions over the invasion immediately stopped scientific collaboration with Russian researchers. While climate scientists agree that the sanctions are necessary, they lament the lost opportunity for vital research in the region, mainly since Russia accounts for nearly half of the Arctic region’s landmass. Only two alternatives can change the Arctic region’s fate: either the Ukraine war should end, or the Russian Chairmanship can finish its two years so that the Arctic Council can begin operations. Somehow, two Arctic States can take the initiative, although they are against the Russian attack on Ukraine and also NATO members: Norway and Canada. Norway is (currently) the only NATO nation sharing an Arctic land boundary with Russia. Despite Norway’s NATO membership, Norway and Russia can negotiate bi-laterally on sovereignty-related issues in the Arctic Region. However, the current scenario does not seem to provide any positive indications for negotiation.

Conclusion

Russian diplomatic overtures in the Arctic p stand against all odds and reveal the possibility of different theoretical approaches. Through the Alaska Purchase of 1867, Russia itself invited its most significant challenge and made the US a next-door neighbour. This deal added interesting aspects to Russian foreign policy. Through this deal, the Russian ambition to exercise a check over the UK through the pincer policy reflected its image as a realist when it decided to sell Alaska to a favourite customer enemy of its traditional enemy, the UK. This deal also let Russia enjoy American support during World War II. Nevertheless, the end of this war caused distance in their relationship.

The Arctic is the theatre of power projection and power play. The US and Russia are competitors in the global arena. Russia is aware that the US-Canada relationship is based on mutual trust, in which the US plays the role of a critical security provider to Canada. Thus, Canada’s destiny in the Arctic is also tied with the US.

The geography of the Arctic has posed a few critical common challenges, and, in such situations, geography becomes more important than ideology. Russian diplomats need to gain Canadian support as part of their strategy against the US. Canadian support benefits Russia in many ways—such as getting help from other Arctic countries and furthering its interests relating to technical support in Arctic matters. Nevertheless, Canada’s dependence on the US for its security has presented a unique friction point preventing one from imagining the exact nature of Canada’s ties with Russia. Is a dependent Canada on the US a blessing in disguise for Russia? Or is it an obstacle to Russia-Canada cooperation on sovereignty over the NWP? These questions remain unanswered.

Here, it is interesting that the two NATO members oppose each other and Russia; yet they live together as civilised neighbours without disturbing the modus vivendi. Still, they are also not resolving any disputes because settling matters would bring the issues to an end. All three have kept their arguments alive, which always offers opportunities to modify their claims and counter-claims according to demands. Today, Russia is a mature Arctic player and is in no hurry to make decisions akin to a new Alaska Purchase. However, the situation of the Russian invasion of Ukraine has nullified many assumptions discussed above. Now Russia is facing severe opposition from its Arctic neighbours. This has created a situation where Russia’s ability to maintain solidarity with Arctic neighbours (on non-military issues) is put under stress. Can Russia continue supporting ongoing research projects that would have shown accountability and responsibility in its role as the Arctic Council chair? Due to the pause in the Arctic Council, we do not know.

The situation of the Russian invasion of Ukraine has nullified many assumptions discussed above. Now Russia is facing severe opposition from its Arctic neighbours.

Nevertheless, Russia has focused on the Ukraine issue and seems to neglect its role in the Arctic region. Russia has not found any scope to avoid the suspension of the proceedings of the Arctic Council. Furthermore, the “Warsaw Pact bitterness” that existed at the time of the creation of the Arctic Council persists. Still, members of the Council must learn to think beyond their Cold War legacy to protect the Arctic. Russia, which remains cautious in dealing with Canada and Norway on Arctic matters, has portrayed itself as an Arctic leader — yet at present, its leadership is missing. This is most egregious given that from an Arctic perspective, now is the most important place and time for Russia, as is the Arctic chair. Russia’s myopia regarding Ukraine has caused the current silence and frozen relations in the Arctic Council. There are indigenous groups of the Arctic nations that are permanent members. These indigenous groups could be allowed to conduct the Arctic Council’s functions. Their roles have been underscored in the historical Murmansk Speech and mandate of the Arctic Council, also which provided them the status of permanent participants.

Dr. Suprita Suman has been a guest lecturer in the Department of Political Science at Patna Women’s College, Patna University, Patna. She completed her Ph.D. on Arctic issues from the Center for Canadian, US, and Latin American Studies, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Dr. Suman is an independent researcher in the traditional and nontraditional security aspects of the Polar region and maritime affairs. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone.

[1] Valery Konyshev and Alexander Sergunin, “Russia’s Policies on the Territorial Disputes in the Arctic,” Journal of International Relations and Foreign Policy, Vol. 2 (1), 2014, 55–83.

[2] Michael Byers, 6. Arctic Straits: The Bering Strait, Northwest Passage, and Northern Sea Route, 267.

[3] Philip J. Briggs, “The Polar Sea Voyage and the Northwest Passage Dispute,” Armed Forces & Society, Vol. 16 (3), 1990, 437–452.

[4] “The United Nation Convention on the Law of Seas,” opened for signature December 10, 1982, U.N. Doc. A/CONF.62/122 (1893), reprinted in 21l.L.M.1261 (1982), https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf.

[5] A. Lukin, “Russia and America in the Asia-Pacific: Will They Ever Move beyond Geopolitics?,” Paper Presented at the Russia and Russian Civilization in the North Pacific Conference, UC Berkeley, May 19, 2011.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Valery Konyshev and Alexander Sergunin, “Russia’s Policies on the Territorial Disputes in the Arctic,” Journal of International Relations and Foreign Policy, Vol. 2 (1), 2014, 55–83.

[8] Vlad M. Kaszynski, “The US-Russian Bering Sea Marine Border Dispute: Conflict over Strategic Assets, Fisheries and Energy Resources,” Russian Analytical Digest, Vol. 20, 2007, Warsaw School of Economics, 2–5.

[9] Philip J. Briggs, “The Polar Sea Voyage and the Northwest Passage Dispute,” Armed Forces & Society, Vol. 16 (3), 1990, 437–452.

[10] Donat Pharand, “Soviet Union Warns United States Against Use of Northeast Passage,” American Journal of International Law, Vol 62, 1968, 92–7935.

[11] “1958 Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone,” April 29, 1958, 15 U.S.T 1606, T.I.A.S. No. 5639, 516 U.N.T.S. 205” (effective September 10, 1964), https://www.gc.noaa.gov/documents/8_1_1958_territorial_sea.pdf.

[12] Margaret Blunden, “The New Problem of Arctic Stability,” Survival, Vol. 51 (5), 2009, 121.

[13] L. Heininen, A. Sergunin & G. Yarovoy, Russian strategies in the Arctic: Avoiding a new Cold War, Международный дискуссионный клуб” Валдай”.

[14] Whiteney P. Lackenbauer, “Mirror Images? Canada, Russia, and the Circumpolar World,” International Journal, Vol. 65, (4), 2010, 879–897.

[15] Haig Cholakian, “Arctic Agenda,” Harvard International Review, Vol. 39, (2), 2018, 48.

[16] H. L. Keenleyside, “The Canada-United States Permanent Joint Board on Defence, 1940–1945,” International Journal,Vol. 16 (1), Winter, 1960/1961, 50–77.

[17] Kenneth Holland, “The Canada-United States Defence Relationship: a Partnership for the Twenty-First Century,” Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, Vol. 20(3), 2014, 241–246.

[18] Government of Canada and Russia, Agreement Between the Government of Canada and Russian Federation Cooperating in the Arctic and North, E10037-CTS, June 18-19, 1992, https://www.treaty-accord.gc.ca/text-texte.aspx?id=100317.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Government of Canada, The Northern Dimension of Canada’s Foreign Policy, 2000, Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, last accessed September 06, 2022, http://library.arcticportal.org/1255/1/The_Northern_Dimension_Canada.pdf.

[21] Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev, “The Speech in Murmansk: At the Ceremonial Meeting on the Occasion of the Presentation of the Order of Lenin and the Gold Star Medal to the City of Murmansk,” October 1, 1987, Novosti Press Agency Publishing House, 1987.

[22] Ronald Purver, “Arctic Security: The Murmansk Initiative and its Impact,” Current Research on Peace and Violence, 11(4).

[23] Arctic Council, Ninth Ministerial Meeting. Iqaluit, Nunavut, Canada, April 24-25, 2015, Information for Press (2015), https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/handle/11374/662.

[24] Ibid.

[25] DECLARATION, TheIlulissatDeclaration.ArcticOceanConference, Ilulissat Greenland, 27–29 May 2008, Ilulissat, Greenland: Arctic Council, retrieved June 13, 2008, https://cil.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/2008-Ilulissat-Declaration.pdf.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Daniel Mc Vicar, “How the Russia-Ukraine War Challenges Arctic Governance,” TheInternationalistandInternationalInstitutionsandGlobalGovernanceProgram, Council on Foreign Relations, https://www.cfr.org/blog/how-russia-ukraine-war-challenges-arctic-governance.