Abstract: The nature and underlying causes of what is happening in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region have a long trajectory. While the international community began to hear about the protests in Hong Kong only a few years ago, the reality is that the tension between both parties goes back to Hong Kong’s roots, from the very moment when the famous rule of ‘One country, two systems’ was created. Although the principles of ‘peaceful coexistence’ and ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ of the People’s Republic of China corresponding to the capitalism prevailing in Hong Kong would be ensured by the Basic Law guaranteeing respect for the institutions and freedoms established by the former British Empire, the reality is much more complex. The rules and laws established in Hong Kong cannot always be applied in their entirety.

Problem statement: How to understand the dynamics between HKSAR wanting to gain greater independence while the PRC has a growing interest in not allowing control of the administered region to slip completely out of its hands?

Bottom-line-up-front: This controversy between Hong Kong and China could be due to certain failures of foresight and understanding in the legal and juridical framework on which the foundations of the system of governance and control in the Hong Kong region are based. The region has been judged from a Western perspective and biased by the Orientalist syndrome.

So what?: The future outlook seems to point to the problematic of what is known as ‘The Hong Kong Question’ still being present in the international community for long and enduring years to come due to a lack of understanding on both sides.

Source: shutterstock.com/Jimmy Siu

A 99 Years Lease

Hong Kong is currently in a period of turmoil. Despite the efforts of China, the concept of ‘One Country, Two Systems’ seems not to have come to fruition in the Hong Kong region, and the prospects for governance and mentalities are different between the two sides. The signing of the Treaty of Nanjing in August 1842 marked a turning point in history, especially in Chinese diplomacy, since it meant the cession of the territory of Hong Kong to the British Empire, whose dominion also ended up extending to the three main regions of Hong Kong (the Kowloon Peninsula and the New Territories).[1] The British Government, in 1898, signed what was to be a 99-year lease for the territory that was to expire in 1997. As that date approached, the time came to negotiate. Thus, in 1984, the cession of the territory of Hong Kong to China was signed between the former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Deng-Xiaopin. Both countries, especially the Chinese giant, knew that this cession would mean a great change for Hong Kong’s residents. With the signing of this cession agreement, also known as ‘Joint Declaration’ (1984), the so-called ‘Basic Law’ was also concluded, which guaranteed a series of conditions and concessions that the Chinese Government had to consider with its new administrative region.[2] The Joint Declaration was ratified and entered into force in 1997 with an effective period of 99 years. China committed itself to administering the region through its famous ‘One Country, Two Systems’ concept.

The Construction of the Legal Framework of Hong Kong and the Impact of the Umbrella Revolution

To understand the current situation in Hong Kong, it is necessary to understand the basic pillars of its legal system, which date back to the 1984 agreement between China and Great Britain. The British granted the territory to the Chinese, but with certain conditions, such as maintaining universal suffrage and a certain relative political freedom, maintaining the capitalist system in the region and, of course, maintaining separation of powers[3] from mainland China.[4]

The legal system of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region is based on the Basic Law enunciated by the National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) following Article 31 of the Constitution of the PRC. In addition, HKSAR has a Chief Executive responsible for administering the region and maintaining bilateral relations between the Chinese Government and the administered region.[5] The executive’s functions include creating, elaborating, and implementing various policies, as well as conducting administrative matters, taking into account the position of the Executive Council. The Chief Executive of the administered region is Carrie Lam, having been elected in 2017 by the Central People’s Government (CPG) of the PRC for a five-year term. Lam grew up in Hong Kong, and she has been committed from the very beginning to trying to respect the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ principle that characterizes Hong Kong.[6]

The legal system of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region is based on the Basic Law enunciated by the National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China following Article 31 of the Constitution of the PRC.

The unicameral parliamentary legislature of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region is a semi-democratically elected body consisting of 70 members, 35 of whom are elected through five geographical constituencies under the proportional representation system and the remaining 35 members through functional constituencies based, for example, on commerce and with limited electorates. The term is granted for a maximum of four years, although the pandemic caused by Covid-19 has been postponed for one season.[7]

In addition, there is also an Electoral Committee composed of approximately one thousand people who have the right to vote, in addition to selecting and proposing the Chief Executive, a chief who generally has the approval of the Chinese Government. This committee has a majority of people loyal to Beijing. This fact may provide some advantages and cause dissatisfaction among the Hong Kong population, a population increasingly at odds with Beijing.

Under this legal framework in the region, tensions began to simmer. The major turning point between Hong Kong & Mainland China was the outbreak of the ‘Umbrella Revolution’, also known as ‘Occupy Central’ (because the protesters occupied the central institutions) in 2014. The protests, in which protesters often utilized umbrellas to shield themselves from tear gas and police force, were the first act of civil disobedience carried out by the administered region and lasted for a long time.[8], [9]

The major turning point between Hong Kong & Mainland China was the outbreak of the ‘Umbrella Revolution’, also known as ‘Occupy Central’ in 2014.

This movement of civil disobedience against the central authorities was not unexpected because there have been signs pointing to the gestation of a latent discontent among the Hong Kong population about the legislation developed by the Chinese regime, as well as the limits to the tolerance that once stood towards the conservative government of president and leader Xi Jinping.[10]

After the Umbrella Revolution: Analysis of the Situation in Hong Kong

After the aforementioned revolution, further events have continued to damage bilateral relations and continue today. The year 2017 saw new elections to the executive branch, placing Carrie Lam in charge of leading the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, who, although hailing from Hong Kong, has a style of governance loyal to Beijing’s policies. Carrie Lam herself spoke out at a press conference in June 2021, arguing that the Hong Kong people must defend the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party so that the rule of ‘One Country, Two Systems’ can be upheld. Specifically, she argues that the country’s constitution must be respected to ensure the implementation and maintenance of the rule enunciated by former leader Deng Xiaoping.[11]

How the Chinese Policies and the 2019 Extradition Law Affected the Hong Kong Population

One of the most contentious issues (also a consequence of the revolution and discontent in Hong Kong) between both parties is the two sides’ different understanding of law and order. Since the beginning of the Umbrella Revolution, Chinese official agencies, as well as the ‘People’s Daily’ newspaper, have claimed that the protests were illegal and against law and order of Hong Kong itself, causing serious consequences.[12]

The protests lasted several weeks, and Beijing’s police deployment to quell the protests resulted in an escalation of tensions that ended in police violence towards the protesting population. This was a clear sign of the political and social awakening of the Hong Kong territory.

The Chinese Communist Party’s policies regarding Hong Kong’s values of freedom and democracy have varied over the years. While in 1998, the Special Administrative Region held its first elections where the Chief Executive was elected by universal suffrage, it is true that over the years and after observing the tremendous economic and business potential, the Chinese regime has become more interested in the internal affairs of the region. Thus, when the Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region is renewed every five years, the new president is now elected through the Election Committee, effectively restricting suffrage despite China’s agreement with the British. Beijing’s political and business interests in this committee usually prevail over the rest. While Beijing announced in 2007 that it would grant the expected universal suffrage in the 2017 elections, in 2014, the Chinese central government introduced the condition that election candidates had to be chosen through the famously Beijing-leaning Election Committee.

While in 1998, the Special Administrative Region held its first elections where the Chief Executive was elected by universal suffrage, it is true that over the years and after observing the tremendous economic and business potential, the Chinese regime has become more interested in the internal affairs of the region.

The Committee is, therefore, a way for Beijing to attend ‘de facto’ to the democratic needs of the region it administers while still exerting control over its great economic, business, and interests. Since the signing of the Sino-British Agreement, the region has followed the Western economic and social model at a general level in all areas. Moreover, bilateral relations between Mainland China and Hong Kong would worsen even further with the advent of the problematic Extradition Law in 2019 (that did not even go into effect), known as the ‘Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation (Amendment) Bill. The proposal of this new law implied that the cases would be reviewed individually to offer a legal solution to those crimes that cannot be solved since there are no extradition agreements. Pro-democracy activists demanded that the government should explain why this new draft law also included extradition mechanisms with Mainland China.[13]

The new proposed law eventually generated a great deal of backlash among the people of the HKSAR because it once again demonstrated Beijing’s opaque attempts to gain increased control over the Hong Kong judicial system. In effect, this law would make it so that any action committed by a citizen of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region that causes problems or causes discontent in Mainland China could result in the legal extradition of those committing the action for trial in Mainland Chinese courts.[14]

The new proposed law caused great discontent and protests among Hong Kong people because, like pro-democracy critics, they feared that Beijing would take advantage of this new law to arbitrarily detain Hong Kong people who openly disagreed with the Mainland Chinese government. The greatest fear was the loss of freedom of speech, as they feared they could be charged and convicted for expressing an opinion contrary to the Chinese Government. In the meantime, there were diverse opinions in which Western and Hong Kong experts alike argued that this new law would be a new attempt by Beijing to exert more control over Hong Kong. When the proposed law was introduced in February 2019 in the Legislative Council, it was immediately criticized by those favoring democracy. A clear example of opposition came from then Camp Convener Claudia Mo, who described the new proposed law as a ‘Trojan Horse’ that could undermine the barriers between Mainland China’s and Hong Kong’s legal systems. Specifically, Mo expressed that this new proposed law caused concern that the Hong Kong population had lost confidence in the Mainland’s judicial system. Therefore, there was great fear that Hongkongers and dissidents could face charges that violated their freedom of speech.[15]

A clear example of opposition came from then Camp Convener Claudia Mo, who described the new proposed law as a ‘Trojan Horse’ that could undermine the barriers between Mainland China’s and Hong Kong’s legal systems.

What began as simple opposition to a new law retroactively affecting Hong Kong people and professionals soon turned into a major pro-democracy revolt, with millions taking to the streets within six months. The protests were set to stay, leading to one of the largest riots in Hong Kong’s history, comparable with the Umbrella Revolution. The riots continued throughout March and April of 2019 after the law’s first proposal in February. In May, the government tried to end the riots by adding several concessions to the bill, such as limiting extraditable offenses, but critics and activists were still unsatisfied. Beijing, for its part, decided to delay the approval of the law, but this did not stop the protesters either, since one of the objectives of the revolution was to achieve the democracy they longed for finally and to put an end to a law they considered arbitrary and unjust for good, and not simply to delay it. Beijing never stated at any time that they were going to cancel this law. This caused the persistent shadow of a law that threatened the interests of the Hong Kong people. However, while the Extradition Law was at last suspended in June and declared de facto ‘dead’ in July, the protesters expected a complete withdrawal which Carrie Lam finally announced in September. This withdrawal marked a milestone in the history of the human rights revolution in Hong Kong. It was a small step towards victory for human rights in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region that still continues today.[16]

Two Different Perspectives: Public Opinion of Hong Kong vs. Official Version of the Government of China

While Mainland China tries to maintain the rule of ‘One country, two systems’ set out by former leader Deng Xiaoping at the time of the administration of the Hong Kong territory, their capacity for action goes a step further, as they inevitably know the great economic and technological power that the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region possesses and are aware that, by becoming more involved in the affairs of that region, this can benefit them to achieve one of their goals set out in their five-year plans. Beijing has tried to incorporate the administered region of Hong Kong under the concept of ’One China. ‘ This approach has strained bilateral relations between both parties, leading to numerous disagreements between them.

Xi Jinping spoke out against Hong Kong’s demonstrations at the Fourth Plenary Session of the party’s Central Committee in 2014, alleging that ‘Some people [in Hong Kong] want to use seeking democracy as a pretext to break away from the jurisdiction and administration of central authorities.'[17]

Since the Umbrella Revolution, the viewpoints between Mainland China (defending the principle of ‘one China’) and the Hong Kong Administrative Region (defending their Basic Law and respecting their capitalist system) have been very diverse. Still, this revolution was unique in that it achieved global attention, gaining support from activists and intellectuals in Mainland China and the international community, including NGOs.

Since the Umbrella Revolution, the viewpoints between Mainland China and the Hong Kong Administrative Region have been very diverse.

However, even after being placated by the central government, protests over Beijing’s anti-Hong Kong Basic Law policies and unfulfilled promises of long-awaited electoral reform to give greater autonomy to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region brought about a new violent and tense political scenario, especially on the part of People’s Republic of China. The protests became so troubling for Beijing that they tried to devise a strategy to bring in the military to quell the riots. The central government was being severely damaged domestically with the erosion of relations with the administered territory of Hong Kong and internationally, giving the image of a country whose control over Hong Kong was slipping from its grasp. The protests continued into 2019 to the point where protestors were able to blockade the airport. As a result, Beijing began accusing these protesters of ‘riots'[18] and claiming that such actions involved serious charges that could result in years of imprisonment. The situation was becoming increasingly serious, and Beijing’s use of police force to placate the so-called ‘riots’ contributed to a rift between society and the police forces. Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam also contributed to the dispersal of the protesters by ordering that they could not cover their faces so that the police could recognize them and impose appropriate penalties. Since that year, the protests have diminished. Still, they continued because, over the years, various Hong Kong protesters and even Hong Kong MPs have been convicted for having organized or participated in the famous protests. This has continued until 2021. Since then, there has been a rift between the two sides that has been impossible to reconcile, and the visions for the future between the two sides are becoming increasingly different.

So, despite the wide international support received in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, supporting the protests in favor of the achievement of human rights in the region and criticizing the Central Government of Mainland China, Beijing remains firm in its ideals criticizing and pointing out the Hong Kong protests as a violent act that goes against the interests of the ‘one country, two systems’ rule. While troops have been sent to the Hong Kong border and within the administered territory, it claims that this has not been to interfere in Hong Kong’s internal affairs but rather to safeguard Chinese national security.

A key pillar of Beijing’s posture is its persistence in the principle of ‘One China,’ thus rejecting all kinds of secessionist acts, dissidents, and foreign international interference in China’s internal affairs, an aspect they consider vital to safeguard their national security as a country.[19] Therefore, the central government recognizes these dissidents and activists who have organized and participated in the Hong Kong pro-democracy protests as secessionists who go against the country’s interests.

A key pillar of Beijing’s posture is its persistence in the principle of ‘One China,’ thus rejecting all kinds of secessionist acts, dissidents, and foreign international interference in China’s internal affairs, an aspect they consider vital to safeguard their national security as a country.

Carrie Lam, the Chief Executive of Hong Kong, has also clearly positioned herself in favor of Beijing’s interests, claiming in June 2021 that Hongkongers must uphold the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party as well as respect the Chinese Constitution to uphold and ensure the rule of ‘One Country, Two Systems.’ While she has opposed protests against the central government, her perspective is that if Hong Kong citizens stand aside and respect Beijing’s decisions, there could still be a solution to the already complicated relations between the two sides. With such a statement, one can see how Lam, despite having grown up in Hong Kong, is still firm in her will and commitment to the decisions and policies that Beijing makes towards the region she administers.[20] Nevertheless, the central government’s position remains strong. They advocate a robust national and international view of China’s sovereignty over its administered territories and try to remain calm to avoid raising attention.

A Way Forward: Activist Demands in Hong Kong

Since 2019, when the most recent large-scale protests took place, activists have made five proposals for the Beijing Government to address. The first was to abolish permanently and not postpone the Extradition Law as they state a clear danger to the freedom of expression of Hong Kong protesters, professionals, and media who may be against Mainland China’s policies. The second is a reform of the electoral law to obtain universal suffrage so that the citizens can democratically elect their leaders without the interference of the Chinese Government, as has been accused in past elections. The third demand seeks an amnesty for all protesters whom the Chinese Government had charged as ‘rioters’ and that no criminal charges or offenses be applied against them. Also, the fourth petition alleges that the central government ceases the protesters’ accusations by classifying them with the definition of ‘riots’ as such classification entails specific penalties.

Finally, the fifth demand of the Hong Kong protesters is to get their longed independence from Mainland China to avoid once and for all that the Central Government interferes anymore in their internal affairs. However, this demand is one of the most complex ones because, in general terms, international recognition is one of the requirements to be recognized as a country. It is clear that many countries or even whole continents, due to their economic relations and commercial interests with China, might not dare to recognize Hong Kong as a fully autonomous country because of the consequences of such a decision.

Finally, the fifth demand of the Hong Kong protesters is to get their longed independence from Mainland China to avoid once and for all that the Central Government interferes anymore in their internal affairs.

All the demands are a key pillar for understanding the aforementioned problematic position of Hong Kong, and they have been widely debated in the international community. However, China resists acceding to the demands despite the international attention and instead prefers to maintain a low profile in its actions towards Hong Kong, always keeping their principle of ‘One China’ concerning their differences.

National Security Law, 2021 Electoral Process and Global Impact

The situation in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region continues to be a matter of debate, especially in countries, institutions, and bodies such as the United States, the UN, and the European Union. Despite the incendiary protests of 2014 and 2019, the Chinese Government has continued to make efforts to exert greater control over Hong Kong. These efforts include the 2020 National Security Law, also referred to as the “Law of the People’s Republic of China on Safeguarding National Security in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region,” which kicked off fresh ire among the Hong Kong population. With continued flare-ups between China and Hong Kong, international observers are also taking notice and engaging in debate about what should be done next; key observers include the UN, the EU, and the United States.

Since then, the region’s situation has become even tense, to the point that this new law has affected many media or social networks. Citizens and media not sympathetic to Beijing fear for their freedom of expression because, as stated above, the Beijing government has not delimited which acts are classified as offensive or not; they have limited themselves to offering a wide range of categories that may not offend. As a result, the demonstrations have not ceased, although they have been carried out less provocatively compared to previous ones to avoid the weight of the new law falling on them. Even so, numerous Hong Kong and foreign demonstrators and professionals have been arrested following (unauthorized) protests against the new National Security Law.[21]

The Case of the Apple Daily and International Impact

One of the most notable cases since the entry of this problematic new law has been the closure of the independent and pro-democratic Hong Kong newspaper ‘Apple Daily.’ This is one of the longest-running newspapers in the history of Hong Kong. It has remained firm in its commitment to democracy and the rights of the administered territory. In 2021, the paper ceased its operations after announcing that certain articles published in the newspaper had violated the principles of the National Security Law. Simultaneously with the newspaper’s closure, six members and executives were arrested by the police.[22] For Hong Kong’s pro-democracy activists, this closure marks a dark day in the region’s history of freedom of expression. This freedom is increasingly being challenged, particularly at the international level, and especially criticized by European parliamentarians in favor of liberal and democratic values.

The European Union has not been the only one to speak out in favor of rights and freedoms in Hong Kong. US President Joe Biden has also questioned Beijing’s position on freedoms in the region, highlighting the case of the Apple Daily newspaper. In response, the Chinese Government has told the US president to stay out of the country’s internal affairs.[23] Even so, while China limits itself to asking for respect for the country’s internal affairs and tries not to interfere too much in international opinions contrary to its sovereignty, criticism from democratic countries and non-allies does not cease.

The European Union has not been the only one to speak out in favor of rights and freedoms in Hong Kong. US President Joe Biden has also questioned Beijing’s position on freedoms in the region, highlighting the case of the Apple Daily newspaper.

In another instance of international outcry, the German Reinhard Bütikofer, member of the Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance and chairman of the Delegation for Relations with the PRC, expressed in his speech on July 8, 2021, in Strasbourg: ‘It is important that we do so because we support Hong Kong’s struggle for its freedoms and democracy. This is not an internal matter. In Hong Kong, freedoms that were once guaranteed for the next 50 years are being systematically dismantled.’[24]

Another key statement to understand the postures from the European Union on this matter is that of Evelyne Gebhardt, member of the Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament and vice-chair of the Delegation for Relations with the PRC, who strongly expressed her opposition to the situation in Hong Kong in the Strasbourg debate: ‘The Member States of the European Union must immediately sanction those responsible in the Hong Kong and Mainland China administration and support the democracy movement in Hong Kong’.[25]

In general, the European Union has criticized the electoral reform in Hong Kong and has anticipated that it will provide greater support to civil society in the region to prevent the ‘one country, two systems’ policy from declining. Josep Borell in Strasbourg expressed that ‘The EU calls on China to act in accordance with its international commitments and legal obligations and to respect the high degree of autonomy of Hong Kong.‘[26]

The Hong Kong Electoral Reform and Its Results in the 2021 Electoral Process

The Apple Daily case and the problematic National Security Law have not been the only topic that has attracted national and international attention to Hong Kong. The delayed electoral process has also drawn criticism. With the advent of Covid-19, Hong Kong’s legislative elections have undergone numerous changes due to the management of the pandemic. Elections had to be delayed twice, but Chief Executive Carrie Lam set December 19, 2021, as the final date for the Legislative Elections. This election has been referred to as the ‘patriots only’ Legislative Elections.

With the advent of Covid-19, Hong Kong’s legislative elections have undergone numerous changes due to the management of the pandemic. Elections had to be delayed twice, but Chief Executive Carrie Lam set December 19, 2021, as the final date for the Legislative Elections.

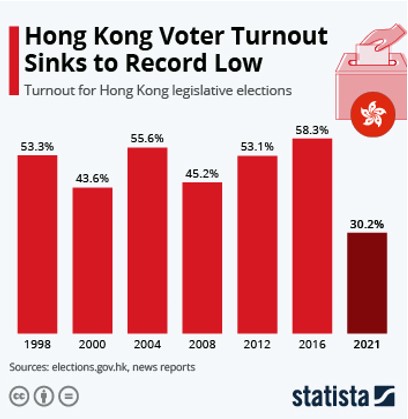

This is due to the new electoral law reform that reserves political power in the HKSAR to those considered ‘patriots’ (supporters of Mainland China). Through this new law, the reform gives Beijing explicit control over the ballot box and leaves little choice for the opposition.[27] Therefore, the turnout has plummeted in these legislative elections, which, being ‘only for patriots,’ have barely left room for the participation of candidates from the Democratic opposition. As expected, the results of the elections have been favorable for the pro-China parties, which have obtained all the seats in an election with a very low turnout of 30.2%.[28]

This graphic representation shows the decline of participation in the 2021 Hong Kong electoral process. This decay could have been fueled because of the electoral reform passed by the Beijing government. Sources: Statista and the official webpage of HK Elections (elections.gov.hk).

The results of these elections also reveal interesting data. In a legislature full of patriots favoring Mainland China, three new political parties emerged to pressure the more traditionalist Beijing loyalists.[29] Hong Kong is still far from an election where the influence of pro-Beijing political and professional parties does not interfere with sovereignty issues, or at least, this is what these “pro-patriotic” elections have shown, where the majority of power has been concentrated in the hands of pro-China parties rather than pro-democracy ones. The international community, led by the G7, has largely condemned the actions of China as suppressing Hong Kong’s right to democracy.

Hong Kong is still far from an election where the influence of pro-Beijing political and professional parties does not interfere with sovereignty issues, or at least, this is what these “pro-patriotic” elections have shown, where the majority of power has been concentrated in the hands of pro-China parties rather than pro-democracy ones.

Conclusions

The Umbrella Revolution and the numerous protests provoked by laws such as the Extradition Law have been clear examples of the opposition of the Hong Kong population and the Hong Kong government against the country that administers them. While there are groups of people who agree with the policies that Beijing is developing to be implemented in Hong Kong, there is also a large majority who are increasingly showing their discontent with what they, along with international supporters, consider a violation of the fundamental rights and freedoms of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

As a result, these protests and dissent against Beijing end up causing a conflict that is ultimately magnified on an international scale. This, consequently, benefits neither Hong Kong nor Mainland China. For the PRC, this is one of the great unresolved internal conflicts that undermines its position as an international actor, as the Chinese giant itself has sought to open up to trade and bilateral relations with other nations, even those that do not share any ideology or worldview. Since its rise to openness and especially since the early 1990s, the goal of the People’s Republic of China has been to grow and become a major power. It is clear that China aims to export its sovereignty to the world through its great economic muscle. Issues such as the “reconquest of Taiwan” and the conflict with Hong Kong are an impediment that obstructs the country’s growth objectives, but this should not and need not interfere with China’s pretensions, as its intentions are purely pragmatic and among the pillars that shape its foreign policy is the demand for non-interference in the country’s internal affairs (Hong Kong, Taiwan, Xinjiang, etc.).

Since its rise to openness and especially since the early 1990s, the goal of the People’s Republic of China has been to grow and become a major power. It is clear that China aims to export its sovereignty to the world through its great economic muscle.

However, while the Chinese Government promotes non-interference in its internal affairs, the reality is quite the opposite. China has reached a point where the situation with the Hong Kong region is becoming increasingly untenable. Protests continue, and the only alternative that Beijing seems to provide is to impose greater control over the region. This control does not favor either Hong Kong or Mainland China, as their strategy of being recognized as an international power and influential global power is being damaged by the still unresolved problem they have with the Hong Kong region. Thus, this strategy of ensuring the ‘One China’ principle while ensuring its sovereignty with respect to its internal affairs in the region also ends up damaging its image as a country that is not able to listen to its citizens, and that curtails the freedoms that the Hong Kong people are so eager to obtain. This is reflected in international criticism by countries such as the United States, international sanctions, and the momentary loss of agreements that could have been highly beneficial for the Chinese giant, such as the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with the European Union, whose prospects are negative.

Given the vast differences and prospects concerning the Hong Kong issue and the international disapproval of the new electoral reform, the ‘Hong Kong Question’ will remain present internationally because of a clear lack of understanding of both worldviews. While Beijing seeks to position itself as a global power and seek economic and trade partners and allies, it is to be expected that its abysmal differences in policies and conceptions of law will face a rocky road to positive international recognition.

Sandra Ramos Martínez; born in Madrid in 1999; Graduated in International Relations at Francisco de Vitoria University in June 2021 and currently pursuing a Master in Geopolitics and Strategic Studies at Carlos III University of Madrid. She has carried out research projects on historical topics and also collaborates since 2022 in different international magazines and media doing analysis and geopolitical research articles on Chinese foreign policy and society. Passionate about writing and international analysis. Her current lines of research and interest are Geopolitics, Asian and European geostrategy, history of the Soviet Union, analysis of the Cold War and the Missile Crisis. She has a growing interest and specialization in Chinese and Japanese culture and society. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone.

[1] J.K. Fairbank, “Chinese Diplomacy and the Treaty of Nanking, 1842,” The Journal of Modern History 12, no. 1 (1940): 1–30, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1870955.

[2] “UNTC,” United Nations Treaty Collection, last accessed August 02, 2022, https://treaties.un.org/Pages/showDetails.aspx?objid=08000002800d4d6e.

[3] This means that the legal system of Mainland China and the administered region of Hong Kong differ.

[4] Lindsay Maizland, “Hong Kong’s Freedoms: What China Promised and How It’s Cracking Down,” Council on Foreign Relations, May 19, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/hong-kong-freedoms-democracy-protests-china-crackdown.

[5] The Joint Declaration and the Basic Law of Hong Kong affirm that the territory can administer itself. However, those agreements also allow Beijing to nominate and elect the Chief Executive who will administer Hong Kong.

[7] Department of Justice of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, “Department of Justice – Our Legal System – Legislative Council,” Department of Justice, September 16, 2020, https://www.doj.gov.hk/en/our_legal_system/legco.html.

[8] Willy Lam, “The Umbrella Revolution and the Future of China-Hong Kong Relations,” IFRI – Institut français des relations internationales | Institut de recherche et de débat indépendant, consacré à l’analyse des questions internationales et de gouvernance mondiale, noviembre de 2014, https://www.ifri.org/en/publications/editoriaux-de-lifri/lettre-centre-asie/umbrella-revolution-and-future-china-hong-kong.

[9] Hong Kong Free Press HKFP, “Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement – Hong Kong Free Press HKFP,” Hong Kong Free Press HKFP, last accessed August 02, 2022, https://hongkongfp.com/the-umbrella-movement-hong-kong/.

[10] Victoria Tin-bor Hui, “Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement: Authoritarianism Goes Global: The Protests and Beyond,” Journal of Democracy 26, no. 2 (2015): 111-121, doi:10.1353/jod.2015.0030.

[11] Candice Chau, “Leader Carrie Lam says Hongkongers must defend leadership of China’s Communist Party – Hong Kong Free Press HKFP,” Hong Kong Free Press HKFP, June 16, 2021, https://hongkongfp.com/2021/06/16/leader-carrie-lam-says-hongkongers-must-defend-leadership-of-chinas-communist-party/.

[12] People’s Daily, “Zhenxi lianghao fazhan jumian, weihu Xianggang fanrong wending” (Cherish the good development prospect, defend Hong Kong’s prosperity and stability), October 01, 2014.

[13] Kris Cheng, “Hong Kong’s new one-off China extradition plan seeks to plug legal loophole, says Chief Exec. Carrie Lam – Hong Kong Free Press HKFP,” Hong Kong Free Press HKFP, Februry 10, 2019, https://hongkongfp.com/2019/02/19/hong-kongs-new-one-off-china-extradition-plan-seeks-plug-legal-loophole-says-chief-exec-carrie-lam/.

[14] Therefore, if we have a look at the principles of the Joint Declaration where clearly the Chinese Government expressed its respect towards non-interference in the internal affairs of the administered region, we can conclude how the situation has changed, as well as the promises and freedoms that at the time remained to be fulfilled.

[15] Chan Holmes, “Explainer: Hong Kong’s Five Demands – withdrawal of the extradition bill – Hong Kong Free Press HKFP,” Hong Kong Free Press HKFP, December 23, 2019, https://hongkongfp.com/2019/12/23/explainer-hong-kongs-five-demands-withdrawal-extradition-bill/.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Cited in Staff Reporter: “Xi Jinping: Some people want to subvert the heavens,” Ming Pao (Hong Kong), October 31, 2014.

[18] The definition that the Beijing government gave to the Hong Kong protesters, calling them ‘Riots’ has clear negative connotations since they are being accused of causing violent disturbances and violating public order, which, according to the law, entails arrest and the possibility of facing harsh prison sentences.

[19] Candice Chau, “Leader Carrie Lam says Hongkongers must defend leadership of China’s Communist Party – Hong Kong Free Press HKFP,” Hong Kong Free Press HKFP, June 16, 2021, https://hongkongfp.com/2021/06/16/leader-carrie-lam-says-hongkongers-must-defend-leadership-of-chinas-communist-party/.

[20] Idem.

[21] Europa Press, At least 53 detained in a demonstration against the new security law that China wants to impose on Hong, europapress.es, https://www.europapress.es/internacional/noticia-menos-53-detenidos-manifestacion-contra-nueva-ley-seguridad-china-quiere-imponer-hong-kong-20200628200210.html. June 28, 2020.

[22] Amnesty International, Hong Kong: Apple Daily closure is dark day for press freedom, August 17, 2021, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/06/hong-kong-apple-daily-closure-is-press-freedom-darkest day/#:%7E:text=Apple%20Daily%2C%20an%20outspoken%20Hong,executives%20in%20the%20past%20week.

[23] ANI, “China dismisses Joe Biden’s remarks on Hong Kong’s Apple Daily closure,” Business News, Finance News, India News, BSE/NSE News, Stock Markets News, Sensex NIFTY, Budget 2022, June 26, 2021, https://www.business-standard.com/article/international/china-dismisses-joe-biden-s-remarks-on-hong-kong-s-apple-daily-closure-121062600093_1.html.

[24] Reinhard Bütikofer, “Debates – Hong Kong, notably the case of Apple Daily – Thursday, 8 July 2021,” European Parliament, July 08, 2021, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/CRE-9-2021-07-08-INT-4-096-0000_EN.html.

[25] Evelyne Gebhardt, “Plenardebatten – Hongkong, insbesondere der Fall von „Apple Daily” – Donnerstag, July 08, 2021,” European Parliament, July 08, 2021, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/CRE-9-2021-07-08-INT-4-094-0000_DE.html.

[26] Europa Press, “La UE carga contra la reforma electoral en Hong Kong y avisa de que “intensificará” su respuesta,” europapress.es, July 09, 2021, https://www.europapress.es/internacional/noticia-ue-carga-contra-reforma-electoral-hong-kong-avisa-intensificara-respuesta-20210609190335.html.

[27] HKSAR Improve Electoral System, “Improve Electoral System – Improving Electoral System (Consolidated Amendments) Bill 2021,” Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau, June 03, 2021, https://www.cmab.gov.hk/improvement/en/bill/index.html.

[28] Macarena Vidal Liy, “Los partidos pro-China de Hong Kong acaparan todos los escaños en las elecciones ‘solo para patriotas’,” El País, December 20, 2021, https://elpais.com/internacional/2021-12-20/los-partidos-pro-china-de-hong-kong-acaparan-todos-los-escanos-en-las-elecciones-solo-para-patriotas.html.

[29] Natalie Wong, Tony Cheung, “Why three new forces could emerge to give Hong Kong legislature a jolt,” South China Morning Post, December 21, 2021, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3160475/what-hong-kong-election-results-reveal-about-new.