Abstract: In tandem with her decades-old practice of using the law to advance revisionist territorial claims, Beijing passed its Coast Guard Law, drawing both apprehension and ire from the claimants of the South China Sea, Japan, and the U.S. Increased traction and controversy surrounding the law are due to entrusting of military-associated functions to what is essentially a civilian agency.

Problem statement: What are the contemporary and potential implications of the law, and how have the regional stakeholders responded?

So what?: The CCG – till now – has avoided using kinetic force, but its sustained presence and coercion necessitate the immediate strengthening of naval capabilities by the parties to the dispute with the aid of the U.S. and other defence partners. The littoral states also need to reach a common understanding with China on the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea draft.

Source: shutterstock.com/Igor Grochev

The People’s Republic of China as a Maritime Great Power

Ever since Chinese President Hu Jintao addressed the Great Hall of the People during the 18th National People’s Congress in 2012, there have been some striking developments regarding the CCG. During his speech, the outgoing head of the CCP made a determinant assertion to implement the strategy for becoming a “maritime great power”.[1] China, alongside other significant developments, created the world’s largest Coast Guard in less than a decade. The Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress passed the Maritime Police Law in January 2021. The legislation has since attracted a fair degree of consternation from the international community since it has essentially granted defence and security functions, among other duties, to the coastal force, which according to domestic law, is not a defence agency. This should not be particularly striking as the ruling party in 2018 placed the coastal force under the overall command of the CCP’s Central Committee and Central Military Commission (CMC) and altered its structure, making it analogous to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).[2]

China, alongside other significant developments, created the world’s largest Coast Guard in less than a decade.

This law can be viewed as an instrument to realize its long-drawn territorial claims by hook or crook, which is not unusual in the Chinese playbook as many legislations, including Land Borders Law, Maritime Traffic Safety rules and Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), and Continent Shelf Act involve expansionist designs.[3] Beijing uses domestic law not only for territorial aggrandizement but also to give a semblance of responsible power. The influence behind this legal approach lies in Sun Tzu’s “Art of War”, which talks about the skill of satiating national interests without fighting and occupying the adversary’s mind.[4] Legal warfare is one of the three pillars of the official “Three Warfares” Strategy, which was incorporated into PLA’s Political Work Regulations in 2003. This approach to warfare uses the law as a weapon to constrain an adversary’s operational space. Using psychological and public opinion warfare as lynchpins creates hesitance in an adversary’s mind regarding the legality of retaliation. This is so because the latter is deemed culpable of violating the law. CCG law is especially concerning when viewed against the backdrop of China’s instrumentalist view of the law. Recourse to legal means is intended to undermine the constestors’ political will and is usually exercised before initiating hostilities.[5]

Recourse to legal means is intended to undermine the constestors’ political will and is usually exercised before initiating hostilities.

Problematic Provisions

The law authorizes CCG Organizations at all three levels to safeguard national sovereignty and security, and protect maritime rights and interests, among other duties. Albeit some of the provisions represent the cause for serious concern. The essence of the problem lies in undefined phrases like ‘illegal entry’ and ‘the sea areas under the jurisdiction of the People’s Republic of China’. These phrases seem like a deliberate response to illicit maritime manoeuvres and the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) 2016 ruling against China’s official claims of ‘historical rights’ over the nine-dash line. While official sources such as the EEZ Act of 1998,[6] a map along with a note verbal sent to the UN,[7] Defense White papers[8] and statements by the CCP members have repeatedly asserted historical waters, its precise extent has never been made explicit. However, there seems to be a general consensus among experts on the confines of the nine-dash line. This approximately covers ninety per cent of the South China Sea, which is manifold more than the standard limit of maritime boundary as per the UNCLOS.[9]

The legislation under the guise of protecting sovereignty and maritime rights authorizes CCG to use coercive measures like detention, forced towing, and inspection of foreign ships. More importantly, some of the provisions violate International Law. For instance, Article 3 does not differentiate between different legal maritime zones as required by the UNCLOS and authorizes CCG to uniformly carry out law enforcement activities throughout the seas and airspace under its jurisdiction. Thus China could deny the legal right of innocent passage to foreign ships throughout the nine-dash line. Furthermore, Article 21 treats foreign government and military ships used for non-commercial purposes in jurisdictional waters as a violation of domestic law and authorizes the CCG to take punitive measures.

In pursuit of her expansionist plan to establish de-facto sovereignty and create “no-go” areas, the CCG has been given the power to delineate ‘temporary maritime security zones’ in virtually any situation. Thus effectively denying the legal right of innocent passage to foreign vessels.

The legislation under the guise of protecting sovereignty and maritime rights authorizes CCG to use coercive measures like detention, forced towing, and inspection of foreign ships.

Taking advantage of the ambiguity in the UNCLOS[10] and Saiga case ruling[11] of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), the CCG law lists various circumstances under which the CCG may use force. Inclusion of ‘obstacles’ and ‘nuisances’ faced while promulgating duties reflects the strong likelihood of pre-emptive aggression. This is due to the broad nature of responsibilities assigned to the CCG, ranging from the protection of maritime boundaries to laying submarine optical cables.[12]

Implications for the South China Sea

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) Foreign ministry labelled the law as a “normal activity of National People’s Congress” while reiterating its position on maritime issues, which remains ‘unchanged’.[13] This naturally evoked sharp and anxious responses from claimant states such as Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, Taiwan, and Malaysia. The Philippines’ response was the sharpest, labelling the CCG law as a “verbal threat of war”.[14]

To impose its diktat in the first island chain, Beijing knows the prerequisite for her ambitions lies in possessing military advantage. While maintaining that its deployments are defensive, China has never ruled out using force.[15] This is conspicuous by the CCG law itself. Foreseeing potential risks, even if the weapons are not used in the short term, China’s territorial intrusions into the contester’s sovereign waters are likely to rise with the establishment of administrative units by Beijing on the Spratlys and Paracel islands, a multitude of artificial, militarized islands within the contested territories. This is due to the nature of responsibilities assigned to the CCG, including protecting maritime boundaries, important maritime targets, activities, islands, artificial islands, and utilization of uninhabited islands. In addition to this, authorizing the CCG with duties to safeguard maritime rights and interests, such as scientific research and marine resource exploration, means that intrusions under the guise of law enforcement would make the regional states more prone to surveillance of strategic assets and exploitation of their respective sovereign resources.[16] The responsibilities assigned to the CCG reflect that the law is rooted in China’s grand strategy. As the legislation remains ensconced in the core national interests of the protection of sovereignty and security along with the maintenance of sustained development.[17] Control over the South China Sea is not only seen as key to China’s prosperity but also tied to CCP’s legitimacy. This is why there is a recurring emphasis on ‘maritime rights’ throughout the law draft.

Authorizing the CCG with duties to safeguard maritime rights and interests means that intrusions under the guise of law enforcement would make the regional states more prone to surveillance of strategic assets and exploitation of their respective sovereign resources.

The law also obligates the coastal agency to prevent and demolish foreign organizations’ structures and buildings, including floating devices. This could have serious ramifications and stoke escalation as all the littoral states except Brunei have outposts on several geographical features claimed by China. These provisions are emblematic of the contemporary sea denial policy of China, in the pursuit of which there has been increased deployment of patrolling ships, and maritime personnel, along with ‘joint flotilla’ operations.[18] The legislation in the pursuit of controlling access to the region contains several provisions to deny the right of innocent passage. The act gives tremendous scope to the coastal force for constraining manoeuvering space of regional stakeholders, with a long-term goal in mind. This is an attempt to buy time to build a ‘world-class’ military to eventually counter what CCP views as ‘long-arm jurisdiction’ by the U.S.[19] With the regional military presence of the U.S. in mind, Beijing remains resolute about developing counter-intervention capabilities, especially the Anti-Access Area Denial (A2AD) Systems, to deter American intervention.[20]

China desires to build capability for ‘informationized local war’ since it has experienced several unsuccessful attempts when denying access to offshore resources to the littoral states.[21]

Another notable concern is the recent synergy of operations between the CCG and PLAN in training and patrolling. This was even replicated in the western Philippine Sea standoff just after a month when the law was passed.[22] Such manoeuvres are not capricious but largely draw upon the law as it also seeks to strengthen coordinating mechanisms for ensuring national security. The law is guided by Beijing’s military strategy, which seeks to implement military strategic guidelines for active defence. The White Paper on military strategy strives to build a ‘combined, multi-functional and efficient marine combat force structure’, so as to enhance naval capabilities for strategic deterrence, maritime manoeuvres, counter-attack, joint operations at sea, and comprehensive defence. This indicates that Beijing’s military objectives in the naval domain are analogous to functions delegated to the CCG by the law.[23]

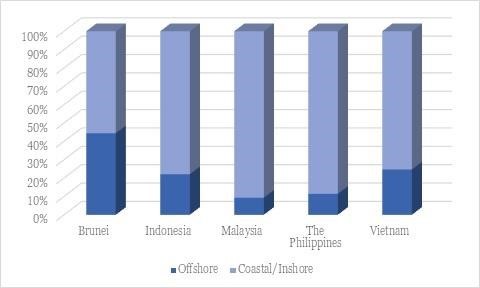

Surface Patrol and Combat Vessels of the countries involved in the South China Sea dispute; Source: International Institute of Strategic Studies

In stark contrast to the growth witnessed in Chinese naval assets, with the CCG fleet of 190,000 tons, the capabilities of other disputed parties are far from ideal. Except for Brunei, the share of claimant states’ offshore patrol and combat ships is below thirty per cent of their aggregate assets. The antiquated nature of some operated vessels, including those of the Philipines commissioned during the Second World War are exacerbating the grave situation.[24] Offshore vessels serving the Navy and Coast Guard are key to a meaningful and sustained presence in exclusive economic zones. Therefore, possession of such vessels is an existential imperative for the claimant states, given recurring incursions by Beijing. Albeit in some of the cases, there has been a strong pushback upon EEZ transgressions, especially by Indonesia and the Philippines,[25] there is no escaping Beijing’s forceful seizure of Mischief Reef[26] or Scarborough shoal[27] from Manila’s de facto control or CCG’s recurring drilling operations and harassment of oil rigs of the littoral states in their respective EEZ.[28] Given Beijing’s widespread buildup and militarization of artificial islands, such as the Paracel, Spratly, and Woody Islands, including deployment of cruise missiles, persistent land reclamation projects, a plenitude of unexplored hydrocarbons and overall balance of power deficit in the contested region,[29] China will always be reluctant to any sincere resolution effort as that could result in compromising on its long-held claims. This was evident in Xi’s last bilateral meeting with the Ex-president of the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte, where he expressed pessimism about the possibility of a resolution anytime soon.[30] In times where major powers determine the rules of the playbook, the balance of power often is an inerrant safeguard of freedom.[31] With no formal central authority to enforce the international rule of law, peace is likely only if symmetry of power exists. This is particularly the case in contemporary geopolitical affairs, wherein many nations confront security dilemmas. Forming foolproof assessments regarding other’s intentions is believed to be far-fetched.[32]

Given Beijing’s widespread buildup and militarization of artificial islands, China will always be reluctant to any sincere resolution effort as that could result in compromising on its long-held claims.

Thus, besides American support, bolstering offshore naval capabilities remains the need of the hour for the parties to the dispute, especially when seen in the backdrop of power projection capabilities that the CCG has gained through the bases at artificial islands, allowing them to patrol across the disputed waters for prolonged periods without returning to the mainland.[33]

Implications for Tokyo and Responses

In Japan’s case, the Maritime Police Law again involves potentially serious consequences for Senkakus/Diaoyu Islands. The ramifications of CCG Law are already beginning to show. For instance, just a week after the law was passed, the Senkakus were circumvented by ten Chinese Coast Guard vessels, compared to six during the previous month. In fact, the monthly average of intrusions into contested islands has grown three-fold after the law’s passing.[34] CCG has attempted to impose fishing regulations around the disputed islet, with several harassment cases reported by the Japanese Coast Guard (JCG). This has continued despite recurring complaints by Japan through diplomatic channels.[35] These cases are likely to increase as PRC aspires to administer the islands to eliminate the possibility of U.S. intervention, which remains guaranteed by the 1951 US-Japan Security Treaty[36] but only on sovereign Japanese territories.

Fumio Kishida administration’s response to the law has been steadfast, giving room for optimism. Tokyo has eschewed the long-drawn ambiguity on the use of force by its Coast Guard, coming out with a bold interpretation of the Police Duties Execution Act.[37] JCG can now fire on foreign vessels in case they encroach or attack. The government also has plans to acquire a dozen additional patrol ships by the end of this year, a clear signal of threat perception which is also conspicuous by official strategic documents, including the Annual Defense Report of 2022, with its emphasis on increasing civil-military fusion of the Chinese, CCG’s intrusions and non-transparent military policies.[38]

Furthermore, the Liberal Democratic Party government has planned to boost its defence expenditure to record levels, i.e., over 2 per cent of the GDP. It has discussed the significance of building ‘counter-attack capabilities’ in light of increased Chinese aggression in both the South and East China Sea.[39] This shows that Tokyo certainly seems to be cognizant of the gravity of the challenge it faces from CCP’s ambitions and its law.

Response of the U.S.

In sync with her Indo-Pacific Strategy, the American administration was quick to express concerns about the CCG Law, with the U.S. State Department stating that “China may invoke this new law to assert its unlawful maritime claims in the region”.[40] Besides the Taiwan issue, preventing Beijing’s expansionism in both the disputed seas has been the main rationale behind increased American presence over the years.

Since 2013, Beijing has ramped up its pace in creating and fortifying islands and advanced military deployments. This has enhanced China’s offensive capabilities. Military infrastructure on some islands means that China can potentially blockade shipping vessels of the claimant states and swiftly take military action on Washington’s allies, the Philippines and Taiwan.[41]

Military infrastructure on some islands means that China can potentially blockade shipping vessels of the claimant states and swiftly take military action on Washington’s allies, the Philippines and Taiwan.

In the aftermath of the law, the U.S. has furthered its naval presence in both the disputed regions, along with the supply of advanced weaponry, particularly to Taiwan and the Philippines.[42] Besides flexing its muscles, Washington promised to ‘revitalize’ decades-old security treaties with its main regional allies, Japan and the Philippines. This is imperative for resisting Beijing’s aggression since the means of deterrence provided under the treaties have been helpful but far from ideal.[43] In tandem with her commitment, the U.S. has expanded the 2014 Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement with the Philippines, which besides giving Washington access to four additional bases within Philippine territory, grants $ 100 million to modernize the moribund forces of the Philippines.[44] The two allies are also working on restarting the joint patrols in the South China Sea, suspended in 2016 by former President Rodrigo Duterte over apprehensions of antagonizing China.[45] Furthermore, the White House has also expanded the 2010 Memorandum of Cooperation (MOC) with Japan to include a joint operation SAPPHIRE (Solid Alliance for Peace and Prosperity with Humanity and Integrity on the Rule of Law-based Engagement), providing capacity-building support to the Coast Guards of Philippines and Vietnam and enhancing operational synergy among the maritime agencies.[46]

Washington remains aware that Beijing’s ‘excessive maritime claims’, with soaring naval capabilities, could snowball into affecting her security interests. China’s EEZ claims in the East China Sea extend as far as the Nansei archipelago. This territory includes Okinawa Prefecture, wherein a majority of the U.S. forces in Japan and over 31 military facilities are stationed.[47] Given its proximity to Taipei, the naval bases at Okinawa are also crucial for keeping a check on Chinese cross-strait aggression and defending Taiwan. China might have the largest navy in terms of overall fleet and personnel. Still, it remains superseded by that of the U.S. in terms of warships and sophistication in technology.[48] Nonetheless, developing the naval capabilities of her allies and the littoral states is a must for the U.S. to effectively deal with Beijing’s grey zone tactics[49] and maintain the defence of the first island chain.

Conclusion

For China, one of the main purposes for becoming a ‘maritime great power’ seems to be the pursuit of territorial aggrandizement. This project has not served it well in terms of international credibility. This is why Beijing has developed an ingenious approach which attempts to varnish its illicit acts as legitimate. The future course of action from the regional stakeholders should not only be unified but also multipronged, leveraging all elements of comprehensive national power, including diplomatic clout for expediting the negotiations on the long-stalled Code of Conduct (COC) in the South China Sea, which needs to be binding and inclusive of all the disputed geographic areas.

For China, one of the main purposes for becoming a ‘maritime great power’ seems to be the pursuit of territorial aggrandizement. This project has not served it well in terms of international credibility.

Much also depends on Washington’s pro-activeness in broad-based securitizing cooperative arrangements with its allies and the claimant nations surrounding the South China Sea. Since the promulgation of the Chinese law, U.S. support to the affected nations has been robust, and it would not be unsafe for the conflictual parties to hedge on American support. Going by Beijing’s previous maritime legislation,[50] the potential geopolitical risks and economic fallouts that virtual implementation of CCG law entails, regional consternation wouldn’t seem understandable, but if Chinese nefarious ambitions or military activities post PCA ruling are any indicators,[51] the claimant states would be well advised to prepare for the future that seems to be muddled with collision course as China sets foot in the era of ‘new great struggle’ in her pursuit of ‘national rejuvenation’.

Araudra Singh is a Diplomacy, Law, and Business student at the O.P Jindal Global University. He is an author of Life in Quotes and has published opinion pieces in The Daily Guardian, The Geopolitics and Chanakya Forum. His interests lie in maritime security of the Indo-Pacific, Chinese foreign policy, South Asia and India’s foreign and security policy. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone.

[1] cn, China, “Full Text: Report of Hu Jintao to the 18th CPC National Congress,” china.org.cn, 2012, http://www.china.org.cn/china/18th_cpc_congress/2012-11/16/content_27137540.htm.

[2] Shigeki Sakamoto, “China’s New Coast Guard Law and Implications for Maritime Security in the East and South China Seas,” Lawfare, August 31, 2021, https://www.lawfareblog.com/chinas-new-coast-guard-law-and-implications-maritime-security-east-and-south-china-seas.

[3] Brahma Chellaney, Edgardo Tsorng, Harsh Ray, P. Kamath, and Rajiv Chopra, “China’s Global Hybrid War: By Brahma Chellaney,” Project Syndicate, December 13, 2021, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/china-xi-jinping-three-warfares-by-brahma-chellaney-2021-12.

[4] Lionel Giles, “Attack by Stratagem,” Essay, In: Sun Tzu on the Art Of War, 17–26. London, UK: E.J BBILL, LEYDEN, 1910.

[5] Dean Cheng, “Winning without Fighting: Chinese Legal Warfare,” The Heritage Foundation, 2012, https://www.heritage.org/asia/report/winning-without-fighting-chinese-legal-warfare/#_ftnref2.

[6] National Congress, “Exclusive Economic Zone and Continental Shelf Act.” un.org, 1998. https://www.un.org/Depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/chn_1998_eez_act.pdf.

[7] Permanent Nations, “Submissions to the CLCS.” United Nations, 2009, https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/commission_submissions.htm.

[8] Anthony H. Cordesman, “China’s New 2019 Defense White Paper,” CSIS, 2019, https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-new-2019-defense-white-paper.

[9] Bec Strating, Chulanee Attanayake, John West, and Rodger Shanahan, “China’s Nine-Dash Line Proves Stranger than Fiction,” lowyinstitute.org, November 09, 2021, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/china-s-nine-dash-line-proves-stranger-fiction.

[10] Sea Division, “UNCLOS – Table of Contents,” un.org, 1982, https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/UNCLOS-TOC.htm.

[11] International Sea, “The M/V ‘SAIGA’ (No. 2) Case (Saint Vincent and the Grenadines v. Guinea),” The M/V “Saiga” (no. 2) case (Saint Vincent and the Grenadines v. Guinea), 1999, https://www.itlos.org/en/main/cases/list-of-cases/case-no-2/.

[12] National Congress, “Coast Guard Law of the People’s Republic of China – Air University,” airuniversity.af.edu, 2021, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/documents/Translations/2021-02-11%20China_Coast_Guard_Law_FINAL_English_Changes%20from%20draft.pdf?ver=vrjG35ymdQsmid0NF66uTA=.

[13] Catherine Wong, “China Calls for Nations to ‘Objectively View’ New Coastguard Law,” South China Morning Post, February 04, 2021, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3120580/china-calls-nations-objectively-and-correctly-view-new.

[14] Yan Yan, “Why Stormy Reactions to China’s New Coastguard Law Are Overblown,” South China Morning Post, February 11, 2021, https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3121247/south-china-sea-why-stormy-reactions-chinas-new-coastguard-law-are.

[15] Oriana Skylar, “Chinese Intentions in South China Sea,” Wilson Centre, 2020, https://fsi-live.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/documents/mastro_paper.pdf.

[16] Idem.

[17] Andrew Scobell, Edmund Burke, Cortez Cooper, Sale Lilly, Chad Ohlandt, Eric Warner, and J.D. Williams, “China’s Grand Strategy,” rand.org, 2020. chttps://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/UNCLOS-TOC.htm.

[18] Collin Koh, “Beijing’s Naval Posture in the South China Sea: A Post-Pandemic Update,” Beijing’s naval posture in the South China Sea: A post-pandemic update, 2022, http://www.maritimeissues.com/security/beijings-naval-posture-in-the-south-china-sea-a-postpandemic-update.html.

[19] China, National Congress, “Full Text of the Report to the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China,” fmprc.gov.cn, 2022, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/zxxx_662805/202210/t20221025_10791908.html.

[20] J. Freedberg, “China’s Fear of Us May Tempt Them to Preempt: Sinologists,” breakingdefense.com, July 13, 2016, https://breakingdefense.com/2013/10/chinas-fear-of-us-may-tempt-them-to-preempt-sinologists/.

[21] Council Information, “China’s Military Strategy (Full Text),” english.gov.cn, 2015, http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2015/05/27/content_281475115610833.htm.

[22] Renato Castro, “The Philippines’ Responses to Chinese Gray Zone Operations Triggered by the 2021 Passage of China’s New Coast Guard Law and the Whitsun Reef Standoff,” Taylor & Francis, 2022, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00927678.2022.2121584.

[23] Idem.

[24] Derek Grossman, “Military Buildup in the South China Sea,” rand.org, 2019, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/external_publications/EP60000/EP68058/RAND_EP68058.pdf.

[25] Stephen Burgess, “Confronting China’s Maritime Expansion in the South China Sea: A Collective Action Problem,” Air University (AU), 2020, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA/Display/Article/2331176/confronting-chinas-maritime-expansion-in-the-south-china-sea-a-collective-actio/.

[26] Renato Cruz de Castro, “The US-Philippine Alliance: An Evolving Hedge against an Emerging China Challenge,” Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs, January 24, 2010, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/370828.

[27] Michael Green Kathleen Hicks, Zack Cooper, John Schaus, and Jake Douglas, “Counter-Coercion Series: Scarborough Shoal Standoff,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, June 27, 2017, https://amti.csis.org/counter-co-scarborough-standoff/.

[28] Stephen Burgess, “Confronting China’s Maritime Expansion in the South China Sea,” media.defense.gov, 2020, https://media.defense.gov/2020/Aug/31/2002488087/-1/-1/1/BURGESS.PDF.

[29] Action Center, “Territorial Disputes in the South China Sea | Global Conflict Tracker,” Council on Foreign Relations, Council on Foreign Relations, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/territorial-disputes-south-china-sea.

[30] Priam Nepomuceno, “PH-US Mutual Defense Treaty Revisions ‘Tricky’: Lorenzana,” Philippine News Agency, 2021, https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1155199.

[31] Robert D. Kaplan, “The South China Sea Is the Future of Conflict,” Foreign Policy, August 15, 2011, https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/08/15/the-south-china-sea-is-the-future-of-conflict/.

[32] Glenn Snyder, “Mearsheimer’s World- Offensive Realism and the Struggle for Security,” jstor.org, 2002, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3092155.

[33] Oriana Skylar, “Chinese Intentions in South China Sea,” Wilson Centre, 2020, https://fsi-live.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/documents/mastro_paper.pdf.

[34] Mayumi Oshige, “China Coast Guard’s Intrusions around Japan’s Senkakus Show Patterns,” The Japan News by The Yomiuri Shimbun, April 06, 2023, https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/politics/defense-security/20230406-101717/.

[35] Idem.

[36] Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Japan-U.s. Security Treaty,” MOFA, 1960, https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/n-america/us/q&a/ref/1.html.

[37] Reito Kaneko, “Japan Can Shoot at Foreign Government Vessels Attempting to Land on Senkakus, LDP Official Says,” The Japan Times, February 28, 2021, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2021/02/25/national/senkakus-east-china-sea-japan-coast-guard-defense/.

[38] Lionel Giles, “Attack by Stratagem,” Essay, In: Sun Tzu on the Art Of War, 17–26. London, UK: E.J BBILL, LEYDEN, 1910.

[39] Tetushi Kajimoto, “Japan Unveils Record Budget in Boost to Military Spending,” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, December 23, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/apan-unveils-record-budget-boost-military-capacity-2022-12-23/.

[40] Reuters Staff, “U.S. Concerned China’s New Coast Guard Law Could Escalate Maritime Disputes,” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, February 19, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-china-coastguard-idUSKBN2AJ2GN.

[41] Kristin Huang, “Fortified South China Sea Islands Help Project Beijing’s Power: Experts,” scmp.com, November 06, 2022, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3198504/fortified-south-china-sea-artificial-islands-project-beijings-military-reach-and-power-say-observers.

[42] Nguyen Thanh Trung, “How China’s Coast Guard Law Has Changed the Regional Security Structure,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, April 12, 2021, https://amti.csis.org/how-chinas-coast-guard-law-has-changed-the-regional-security-structure/.

[43] Subel Rai Bhandari, “US-Philippines Defense Alliance Needs Overhaul, Manila Says,” Benar News, September 13, 2021, https://www.benarnews.org/english/news/philippine/us-philippines-defense-treaty-overhaul-09102021163328.html.

[44] Karen Lema, “Explainer: Why U.S. Seeks Closer Security Cooperation with the Philippines,” Reuters, Thomson Reuters, February 02, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/why-us-seeks-closer-security-cooperation-with-philippines-2022-11-20/.

[45] Reuters, “South China Sea: After Run-in with Chinese Ship, Manila Plans Joint US Patrols,” South China Morning Post, May 08, 2023, https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/southeast-asia/article/3219818/south-china-sea-after-near-collision-chinese-vessel-philippines-says-joint-patrols-us-may-be-months.

[46] Aaron Lariosa, “U.S. and Japan Coast Guards Expand Cooperation, Begin Operation Sapphire,” Overt Defense, May 23, 2022, https://www.overtdefense.com/2022/05/23/u-s-and-japan-coast-guards-expand-cooperation-begin-operation-sapphire/.

[47] Lindsay Maizland, “The U.S.-Japan Security Alliance,” Council on Foreign Relations, Council on Foreign Relations, 2021, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/us-japan-security-alliance.

[48] Benjamin Mainardi, “Yes, China Has the World’s Largest Navy. That Matters Less than You Might Think,” The Diplomat, April 13, 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/04/yes-china-has-the-worlds-largest-navy-that-matters-less-than-you-might-think/.

[49] Bonny Lin, Cristina L. Garafola, Bruce McClintock, Jonah Blank, Jeffrey W. Hornung, Karen Schwindt, Jennifer D. P. Moroney, et al, “How and Why China Uses Gray Zone Tactics,” RAND Corporation, March 30, 2022, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RBA594-1.html.

[50] Zhang Chun, “China Targets Distant-Water Criminals with New Fisheries Law,” China Dialogue Ocean, February 10, 2022, https://chinadialogueocean.net/en/fisheries/12714-china-fisheries-law-distant-water-fishing/.

[51] Oriana Skylar, “Amazon Web Services,” Wilson Centre, 2020, https://fsi-live.s3.us-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/documents/mastro_paper.pdf.