Abstract: Cognitive warfare has taken advantage of the 21st century’s technological advances to evolve and alter the way humans think, react, and make decisions. Several stages utilise cyber security technological infrastructure, especially in the initial stages of content creation, amplification and dissemination. In fact, evidence points to the use of cognitive threats as a means of inciting wider cyberattacks and vice versa. The war in Ukraine has accounted for 60% of observed cognitive incidents, with Russia being the main actor in this context. The DISARM framework outlines the two nations’ prominent Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) as the development of image-based and video-based content, the impersonation of legitimate entities, degrading adversaries, and the use of formal diplomatic channels. Combining the DISARM and ATT&CK frameworks could enhance the analysis and exchange of threat intelligence information.

Problem statement: How to analyse the relationship between cyber security and cognitive warfare and what lessons can we learn from the war in Ukraine?

So what?: Although the DISARM framework is still in the early stages of its development, it provides an invaluable step towards opening up the dialogue on and understanding of FIMI behaviours across the community. Adopting cyber security concepts for the rapid build-up of capacity and resilience in the cognitive domain would be beneficial. In parallel, educating a multi-disciplinary workforce (and society as a whole) against combined scenarios of cognitive warfare and cyberattacks would help to improve their resilience.

Marking a Step in an Ever-Evolving World

While militarisation continued to decrease across the globe for 15 years prior to 2022, the world has not become more peaceful. According to the 2022 Global Peace Index, 70% of countries have reported a decline in peace over the past 15 years, with discourse, polarisation, social division, violent demonstrations, and conflict affecting societies globally.[1] The prevalence of misinformation and disinformation is considered to be the most significant catalyst. The underlying aim of the two is ostensibly rooted in destabilising trust in information and political processes among the masses. Misinformation and disinformation are also seen as potentially posing a more severe threat than a hot conflict or weapons of mass destruction over the next ten years. At the same time, cyberattacks consistently remain among the top 10 risks in global risk rankings, and their significant impact highlights the need to boost our level of preparedness across the globe.[2]

According to the 2022 Global Peace Index, 70% of countries have reported a decline in peace over the past 15 years, with discourse, polarisation, social division, violent demonstrations, and conflict affecting societies globally.

Relating the Concepts

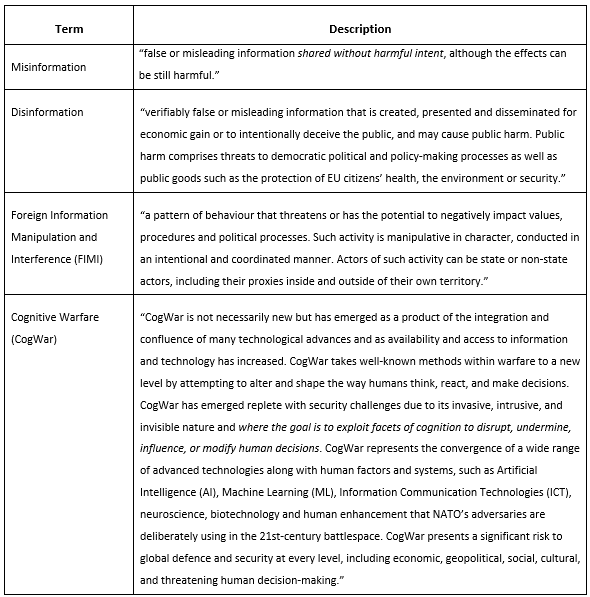

As a first step towards investigating the relationship between cybersecurity and cognitive warfare, it is important to consider relevant terms. Due to the dynamic nature of the threats in question, terminology may vary depending on the source or the time of publication. In other words, the terms below, including disinformation and FIMI (explained below), are not mutually exclusive semantically. This suggests the need to review such overlaps by adopting an interdisciplinary approach and perspective. It is also important to recognise that conventional warfare is expanding into cyberspace and the information space, where FIMI threats are expected to play a significant role (e.g., using cyberinfrastructure to dismiss or distort information on casualties or the impact of conventional warfare operations).

Based on the definitions above, there are many similarities between misinformation and disinformation, but also between FIMI and cognitive warfare. According to the 1st European External Action Service (EEAS) Report on Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference Threats (FIMI) and the EEAS Strategic Communications (STRATCOM) Activity Report, both misinformation and disinformation are defined as fake content, but disinformation is distinguished by the intentional creation and sharing of false information. The same report introduces FIMI threats, which are characterised by their intentional nature and coordinated manner, and which also have actors, intentions and features in common with cognitive warfare.[3], [4] The NATO Science and Technological Organization (STO) Human Factors and Medicine (HFM) Exploratory Team (ET) 356 describe Cognitive Warfare (CogWar) in greater depth and highlight its reliance on human factors and technology, such as ICT, AI, neuroscience, biotechnology and human enhancement.[5]

Professor Seumas Miller also recognises that cognitive warfare focuses on altering how a target population thinks, and hence how it acts by weaponising public opinion to influence public and governmental policy and destabilise public institutions. Furthermore, he identifies the origins of cyber warfare in psychological operations (PSYOP) and information warfare, noting its heavy reliance on new ICT technologies, social media platforms, cybertechnologies (e.g., bots) and, notably, AI. He also pinpoints disinformation and sophisticated psychological manipulation techniques as key features of cognitive warfare.[6]

Cognitive warfare focuses on altering how a target population thinks, and hence how it acts by weaponising public opinion to influence public and governmental policy and destabilise public institutions.

The definition of cyber security has also evolved to reflect its ubiquity, pervasiveness, and rapidly evolving nature. The latest ISO/IEC TS 27100:2020 standard defines it as “safeguarding of people, society, organisations and nations from cyber risks. Safeguarding means keeping cyber risk at a tolerable level”. Cyber risk is defined as “[the] effect of uncertainty on objectives of entities in cyberspace, where cyber risk is associated with the potential that threats will exploit vulnerabilities in cyberspace and thereby cause harm to entities in cyberspace”. In turn, cyberspace is defined as “[an] interconnected digital environment of networks, services, systems, people, processes, organisations, and that which resides on the digital environment or traverses through it”.[7]

Cyber Security for Representing and Understanding FIMI Threats

One example of interdisciplinary collaboration within the FIMI defender community is the creation of the DISARM (DISinformation Analysis & Risk Management) framework, designed to represent a knowledge base and taxonomy of known FIMI adversarial behaviours, as well as defences against them.[8], [9] It is inspired by MITRE ATT&CK®, a curated knowledge base and model for cyber adversary behaviour from the cyber security domain. Both frameworks are open source, aiming to fight cyber and FIMI threats respectively by sharing threat intelligence data, conducting analyses, and coordinating effective actions. The DISARM Red framework represents Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) of incident creator FIMI behaviours, whereas DISARM Blue describes potential response options.

When examining the cognitive warfare operations in the war in Ukraine, one can identify numerous examples of FIMI threats that the DISARM framework can shed light on. According to the 1st EEAS Report on FIMI threats, the war in Ukraine accounted for 60% of observed incidents.[10] In the context of the invasion, incidents have sought to distort the narrative and shift the blame onto other actors, such as Ukraine or the EU. Russia is the main actor, utilising a plethora of techniques, the most prominent of which are outlined by the DISARM framework as follows:

● Develop image-based and video-based content (T0086, T0087)

● Impersonate legitimate entities (T0099)

● Degrade adversaries (T0066)

● Use formal diplomatic channels (T0110)

The development of fabricated images and video content was used to distort facts by reframing events, degrading an adversary’s image or ability to act, and discrediting credible sources. Aiming to reach a wider audience, the content was translated into multiple languages. Observed incidents featured at least 30 languages, 16 of which were EU-based. Formal diplomatic channels were used to deliver content, distort facts by reframing the context of events, and degrade adversaries. Fabricated content was then amplified and distributed by cross-posting across multiple groups and platforms, which propagated it to new communities among the target audiences or to new target audiences.[11]

Russia’s cognitive warfare operations in Ukraine are evidently designed to:[12]

● Dismiss allegations: e.g., claiming that Kyiv staged the Bucha massacre to discredit the Russian army.

● Distort the narrative and twist the framing: e.g., the alleged discovery of U.S. biolabs in Ukraine to justify the “special military operation”.

● Distract attention and shift the blame onto a different actor or narrative by “scapegoating”: e.g., claiming that the West demonises Vladimir Putin and hinders negotiations.

● Dismay to threaten and frighten opponents: e.g., intimidating Russia’s political opponents.

● Divide to generate conflict and widen divisions within communities: e.g., spreading the hoax that a Ukrainian court had ordered the demolition of an Orthodox church.

According to the 1st EEAS Report on FIMI threats, the war in Ukraine has also provided evidence of alignment and support between Russia and the People’s Republic of China (PRC), with some content (such as the alleged U.S. military biolabs in Ukraine) being amplified by PRC-controlled media and official social media channels. There were also instances of providing a platform for sanctioned Russian media outlets.[13]

According to the 1st EEAS Report on FIMI threats, the war in Ukraine has also provided evidence of alignment and support between Russia and the PRC, with some content being amplified by PRC-controlled media and official social media channels.

FIMI threats utilise cyber security technological infrastructure, especially in the initial stages of content creation, amplification, and dissemination. In fact, specific cyberattacks could be considered a precursor to FIMI incidents and vice versa, which further supports the case for using both the DISARM and ATT&CK frameworks in combination. For instance, cyberattacks could be used to obtain information that could later become the basis for fake content creation in information operations. Similarly, stealing voter registration data could support and develop specific narratives, whereas obtaining personal email addresses could be used to disseminate content. Fake accounts could be created, existing accounts compromised to establish legitimacy, and websites hacked to display fake content.[14]

Finally, one example which illustrates that FIMI incidents serve as a precursor to cyberattacks would be the March–October 2022 incidents, where content was routinely posted by a hacker group through Telegram, and systematically amplified by Russian state-controlled outlets to incentivise with cryptocurrencies any cyberattacks against Westerners “lying” about the Ukrainian invasion.[15]

It is also important to consider the effect that FIMI threats could have on the cyber security domain. As the emergence of deepfakes and “disinformation-for-hire” services could lead to novel, highly sophisticated and successful impersonation attacks and deception techniques, understanding FIMI adversarial behaviours would also help build our resilience against them and maintain our security posture.[16]

Although the DISARM framework is still in the early stages of its development, it marks an invaluable step towards facilitating the dialogue on, and understanding of, FIMI behaviours across the community. It paves the way for improving the analytical maturity of FIMI threats and standardising threat intelligence information exchange. Moreover, it exemplifies the benefits of adopting cyber security concepts in the cognitive warfare domain, illustrating that cyber security could contribute to the rapid build-up of capacity and resilience in the cognitive domain.

Thoughts on Countering Cognitive Threats

Western communities’ level of preparedness for cognitive threats is continuously improving, with threat intelligence communities monitoring, analysing, and preparing defences against such pervasive threats. Having the infrastructure in place to detect, model, study and communicate the evolution of cognitive threats is key to devising effective defence strategies. The strong links and relationships between cognitive warfare and cyber security could be hugely beneficial.

Western communities’ level of preparedness for cognitive threats is continuously improving, with threat intelligence communities monitoring, analysing, and preparing defences against such pervasive threats.

However, technology alone will not suffice; education, simulation, and gamified learning could be useful to support awareness-raising and information literacy campaigns, eventually aiming to improve the resilience of a multi-disciplinary workforce against combined scenarios of cognitive warfare and cyberattacks. Recognising the importance of positive security to support the transition from awareness to a security culture, in which secure behaviour is integrated and becomes the default option, will be key.[17]

Dr Maria Papadaki is an Associate Professor in Cyber Security at the Data Science Research Centre, University of Derby, UK. She has been an active researcher in the cyber security field for more than 15 years, focusing on incident response, threat intelligence, maritime cybersecurity, and human-centred security. Her research outputs include 70+ international peer-reviewed publications in this area. Dr Papadaki holds a PhD in Network Attack Classification and Automated Response, an MSc in Networks Engineering, a BSc in Software Engineering, and professional certifications in intrusion analysis and penetration testing. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent those of the University of Derby.

[1] Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), “Global Peace Index 2022: Measuring peace in a complex world,” June 2022, https://www.visionofhumanity.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/GPI-2022-web.pdf.

[2] World Economic Forum, “The Global Risks Report 2023: 18th Edition Insight Report,” January 2023, https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2023.pdf.

[3] European External Action Service (EEAS), “1st EEAS Report on Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference Threats. Towards a framework for networked defence,” February 2023, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/2023/EEAS-DataTeam-ThreatReport-2023..pdf.

[4] European External Action Service (EEAS), “2021 STRATCOM Activity Report: Strategic Communication Task Forces and Information Analysis Division (SG.STRAT.2),” 2021, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Report Stratcom activities 2021.pdf.

[5] Yvonne Masakowsi, and Janet Blatny, “Mitigating and responding to cognitive warfare,” NATO Science and Technical Organization, March 2023, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/trecms/AD1200226.

[6] Seumas Miller, “Cognitive warfare: an ethical analysis,” Ethics Inf Technol 25, 46 (September 2023), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-023-09717-7.

[7] ISO/IEC 2700, “Information Technology – Cybersecurity – Overview and concepts” (2020).

[8] “DISARM Framework Explorer,” DISARM Frameworks, last modified November 2023, https://disarmframework.herokuapp.com/.

[9] Erika Magonara, Apostolos Malatras, “Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) and Cybersecurity – Threat Landscape,” ENISA, December 2022, https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/foreign-information-manipulation-interference-fimi-and-cybersecurity-threat-landscape/.

[10] European External Action Service (EEAS), “1st EEAS Report on Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference Threats Towards a framework for networked defence,” February 2023, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/2023/EEAS-DataTeam-ThreatReport-2023..pdf.

[11] Idem.

[12] Nicolas Hénin, “FIMI: Towards a European redefinition of Foreign Interference,” EU Disinfo Lab, April 2023, https://www.disinfo.eu/publications/fimi-towards-a-european-redefinition-of-foreign-interference/.

[13] European External Action Service (EEAS), “1st EEAS Report on Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference Threats. Towards a framework for networked defence,” February 2023, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/2023/EEAS-DataTeam-ThreatReport-2023..pdf.

[14] Erika Magonara, Apostolos Malatras, “Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) and Cybersecurity – Threat Landscape,” ENISA, December 2022, https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/foreign-information-manipulation-interference-fimi-and-cybersecurity-threat-landscape/.

[15] European External Action Service (EEAS), “1st EEAS Report on Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference Threats. Towards a framework for networked defence,” February 2023, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/2023/EEAS-DataTeam-ThreatReport-2023..pdf.

[16] Joseph Buckley, and Stina Connor, “Cyber Threats: Living with Disruption,” Control Risks and AirMic, October 12, 2021, https://www.controlrisks.com/our-thinking/insights/reports/cyber-threats-living-with-disruption.

[17] Sidney Dekker, Just Culture: Restoring Trust and Accountability in Your Organization (Third Edition, CRC Press, 2016).