Abstract: The manoeuvrist approach is highly relevant for militaries facing stronger adversaries, and its principles are, therefore, taught in the Estonian Military Academy. For evaluating the effectiveness of teaching methodology and its outcomes, essential maneuverist principles were identified, and their prominence was determined by analysing interviews with the lecturers and, thereafter, student’s written assignments. The study highlights both the principles that are generally adhered to and those that are missing while also addressing the challenges of their teaching and assessment.

Problem statement: How to prepare officers to apply the principles of the manoeuvrist approach?

So what?: Military academies should strive to prepare officers efficiently. Considering Russia’s increased threat, Estonia must revise and assess its current practices.

Source: shutterstock.com/Oleg Proskurin

The Preferred Way

The manoeuvrist approach, as NATO’s overarching approach for conducting land tactical operations, is widely accepted as the preferred way of solving tactical problems and achieving success while conducting military operations and activities. This is an indirect approach,”[…] which seeks to gain a position of psychological advantage over the adversary”,[1] and thereby emphasises the importance of perception created by different lethal and non-lethal means. While battles are often won in the minds of opposing commanders, the execution of necessary military actions on the battlefield still remains crucial. Therefore, the quest for the most effective methods of engaging military forces in land tactical operation is ongoing. The manoeuvrist approach aims to minimise losses, limit damage, and conserve resources while effectively restricting the adversary’s freedom of action, even with inferior forces.[2] This strategy is vital for small states with limited armed forces that must defend themselves against a superior enemy. The Estonian Defence Forces are organised as a reserve-based army with limited personnel and equipment. To hold ground until NATO reinforcements arrive, Estonia has prioritised the development of land-centric armed forces. These forces are tasked with defending critical terrain and key areas essential for the successful integration of incoming allied support.

The manoeuvrist approach, as NATO’s overarching approach for conducting land tactical operations, is widely accepted as the preferred way of solving tactical problems and achieving success while conducting military operations and activities.

For NATO’s border states, such as Estonia, which must be prepared to defend against a potential adversary like Russia with minimal reinforcements from allies in the initial phases of conflict, it is vital to adopt a military mindset that focuses on outmanoeuvring the aggressor and achieving victory with more agile and lighter land formations than those of the opponent.

The Estonian Defence Forces, even as part of the NATO Force Structure, will likely have to face heavier[3] and better-supported enemy land formations. Although the manoeuvrist approach is traditionally applied at the formation[4] level, smaller armed forces must also integrate these principles at the unit and even sub-unit level.[5] This necessitates that officers in the Estonian Defence Forces actively understand and adopt the manoeuvrist approach, starting at least at the battalion commander level or even below. For professional military education institutions, this presents the challenge of developing an effective method to teach the application of the manoeuvrist approach.

Although the manoeuvrist approach is traditionally applied at the formation level, smaller armed forces must also integrate these principles at the unit and even sub-unit level.

As noted by McCoy and others,[6] the principles of manoeuvre warfare have been established as a core philosophy for warfighting in the U.S. Marine Corps for decades. Yet, their practical application is seldom observed in training environments. At the Estonian Military Academy (EMA), the teaching of the manoeuvrist approach dates back about 20 years, with more advanced study designs, materials, and tasks being implemented over the past two years.

The Estonian Defence Forces’ Manoeuvrist Principles

The NATO doctrine does not provide a specific definition of manoeuvrist principles. Instead, it outlines the aims of the manoeuvrist approach, which are “to seize and hold the initiative, and to attack the adversary’s understanding, will, and cohesion.” It describes the methods to achieve these goals. NATO identifies eight key fundamentals—tempo, surprise, pre-emption, momentum, simultaneity, exploitation, and avoiding culmination—as universal methods for seizing, holding, and retaining the initiative. These fundamentals are not tied to any specific type of operation or branch of the land forces. In addition, NATO doctrine describes three ways to attack the enemy’s understanding, will, and cohesion: dislocation, disruption, and destruction. These concepts are similar to the ‘defeat mechanisms’ defined in U.S. doctrine as “methods through which friendly forces accomplish their mission against enemy opposition.”[7] Although the terminology and number of mechanisms differ between NATO and U.S.[8] doctrine, the fundamental idea of describing ways to achieve victory in battle is the same.

According to Hoffman,[9] the U.S. Marine Corps doctrine does not explicitly refer to defeat mechanisms, but these concepts are well understood by its officers. Hoffman also notes that the UK land doctrine[10] lists the same three methods (destruction, dislocation, disruption) to attack an opponent in land combat as NATO, referring to them as constructs with the same aim: to describe how to fight. The UK Army’s approach goes further, naming this as a “philosophy of war, manoeuvrism, or a manoeuvrist approach,” yet the essence of the theory remains aligned with NATO doctrine. Despite the variations, the concept is widely accepted across Western military doctrine as a universal approach to combat.[11] The challenge in teaching this universal concept lies in providing tangible explanations and battlefield examples to convince learners to adopt it in their planning and execution of land operations. While the learners understand the principle in theory, it is often difficult to illustrate the concept with practical examples from training events. In other words, we grasp the philosophical idea behind the manoeuvrist approach, but we struggle to effectively explain it using tactical actions on the battlefield.

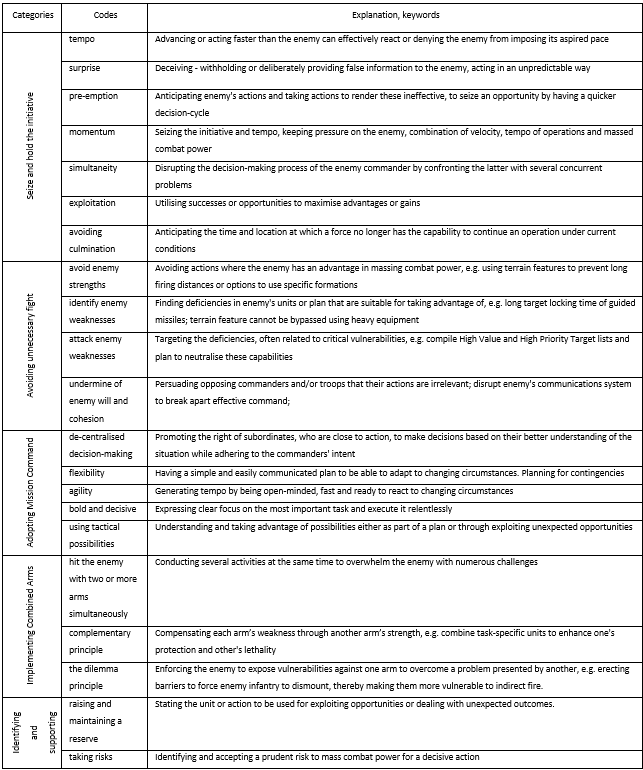

Previous studies at the Estonian Military Academy have sought to apply the theory of the manoeuvres approach to lower levels of land combat, specifically from the perspective of a manoeuvre unit.[12] This study focused on how an infantry battalion could use the manoeuvrist approach against a more powerful enemy force in the defence of Estonia. The primary goal was to identify practical guidance for an infantry unit commander on implementing the manoeuvrist approach when planning and executing offensive operations. Although the study concentrated on offensive actions, the theoretical analysis was broadly applicable, independent of the specific type of operation. The study ultimately formulated four key principles of the manoeuvrist approach that are vital for successful military operations: “avoiding unnecessary fights, adopting mission command, implementing a combined arms approach, and identifying and supporting the main effort.”[13] These principles are not new, as they have been referenced by various authors and described in different doctrines. However, the study aimed to describe how these principles would manifest in unit-level military operations. The findings are intended to enhance training methodologies and help formulate criteria for planning products that adhere to the manoeuvrist approach.

Previous studies at the Estonian Military Academy have sought to apply the theory of the manoeuvres approach to lower levels of land combat, specifically from the perspective of a manoeuvre unit.

![Principles of Manoeuvrist Approach in Estonian Defense Forces (Based on Aija, 2011[14]).](https://tdhj.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Kirschbaum_Saalik_Aija_1.png)

Principles of Manoeuvrist Approach in Estonian Defense Forces (Based on Aija, 2011[14]).

To reach the enemy’s critical vulnerabilities in a land battle, one must avoid committing troops to engagements with enemy security forces unless it directly impacts the enemy’s actions. As Lind suggests,[16] the goal of the manoeuvrist approach is not to engage in direct destruction but to bypass and defeat the enemy by achieving a positional advantage. This requires identifying gaps in the enemy’s formation, where we can bypass main defensive positions to strike at the critical vulnerability.[17] These gaps, often referred to as “soft spots,” must be identified before engaging the enemy. It is important to note that these gaps may not only be areas with no troops but also areas where the enemy’s forces are less capable or not fully prepared for combat. To avoid unnecessary fights, conducting a thorough analysis of both the enemy and the environment where the battle will take place is crucial.

Adopting mission command is a prerequisite for achieving the principle of avoiding unnecessary fights. It ensures that commanders on the ground make decisions on the battlefield rather than by higher headquarters. NATO defines mission command as “the preferred command and control philosophy for allied forces,” a style of command that describes the ‘what’, without necessarily prescribing the ‘how’”.[18] This command philosophy is considered the most effective way to overcome the uncertainty and chaos of combat.[19]

This command philosophy is considered the most effective way to overcome the uncertainty and chaos of combat.

Mission command is more than just the decentralised execution of a battle plan – it is a philosophy that embodies values such as openness to innovative ideas and the flexibility to change plans or actions when necessary. The openness to new ideas is not something that has always been characteristic of today’s Western society, especially in such a conservative field as the military. We are still stuck in the desire to avoid mistakes at all costs and to feel secure in our decisions. Taking risks is not inherent to us. To achieve this flexibility, the battle plan itself must be simple enough to allow for adaptation. Any changes require boldness and decisiveness, focusing on exploiting every tactical opportunity and generating greater tempo. Tempo in turn, enables commanders to move faster within the OODA loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act) and is not possible without agile actions by the troops on the ground. Agility, on the other hand, is not possible without well-rehearsed drills.

Identifying and supporting the main effort refers to ensuring unified action on the battlefield. It is not just about maintaining tempo; actions must also have the ‘right focus.’ In Western military doctrine, this ‘right focus’ in planning and executing military operations is known as the ‘main effort,’ or perhaps even more aptly in German as ‘Schwerpunkt’. The main effort is defined as ‘a concentration of forces or means in a particular area and at a particular time to enable a commander to bring about a decision”.[20]

At the tactical level, the main effort is typically a sub-unit that plays the most significant role in achieving the higher unit’s mission. In the context of the manoeuvrist approach, the main effort means that the commander has made a deliberate decision and taken risks to concentrate forces where success is most desired. To maintain momentum, the commander must have a reserve ready to exploit the success of the main effort.[21] All other actions and effects must support this effort.

Implementing a combined arms approach can manifest itself in trying to achieve the dislocation[22] of the enemy and not so much destroying it. This approach, introduced in the context of land battles by Lind and Leonhard,[23], [24] emphasises the need to create multiple dilemmas for the opponent. The combined arms concept seeks to attack the enemy with two or more arms simultaneously so that the opposing commander’s actions to defend against one threat make them more vulnerable to another.

Method

As the principles of manoeuvrist approach are considered highly relevant aspects of contemporary military competence, the current study aimed to research teaching it from input – the lecturers’ perception of what should be taught and how – up to the outcome presented by students. A qualitative approach was chosen as a research method to reveal patterns in understanding the manoeuvrist approach in military education and to trace the manifestations of the manoeuvrist approach principles in students’ assignments.

As the principles of manoeuvrist approach are considered highly relevant aspects of contemporary military competence, the current study aimed to research teaching it from input up to the outcome presented by students.

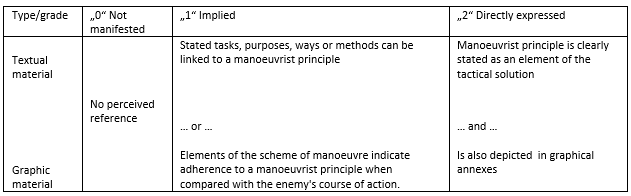

First, three semi-structured interviews with lecturers were conducted. Their perception helped to understand the current state of implementing the manoeuvrist approach principles in preparation for future field grade officers, as well as to prepare the method of the study, to choose the most suitable materials of students’ work and to complete the codes and categories of the coding guidelines. Then, a set of student assignments (both written and graphic material) were analysed using qualitative content analysis. The coding guidelines were prepared according to the principles of manoeuvre warfare theory[25], [26] and modified to suit the Estonian context.[27]

The Coding Guidelines; Source: Authors.

The primary data utilised in the analysis of the Advanced Officer Course students’ assignments was derived from two types of sources. The first type were written commander’s decisions where students, following a brief introduction to the brigade’s battle plan, drafted an infantry battalion commander’s assessment, intent and planning guidance for the forthcoming operation within 60 minutes. The decisions involved eight different tactical problems varying in operational conditions, types of objectives and force composition but only four decisions from 10 students (out of 25) were analysed. Out of these, three were offensive operations with tasks to seize, destroy and secure in addition to one defensive operation with a task to retain.

The second source comprised of 12 operation orders composed during staff planning exercises. In these exercises, the students assumed the roles of commander and staff officers, respectively, for the purpose of conducting battalion defensive operations. In comparison to the first source, this afforded them sufficient time to conduct a comprehensive analysis and planning.

As for the textual material, such as interview transcripts or students’ written assignments, a clear-meaning component was used as a coding unit either explicitly or latently. For the interviews, a combined approach of content analysis was used, taking sub-themes of manoeuvre warfare theory as a basis for the categories but leaving the creation of codes open and inductive to grasp the perception of interviewees as originally as possible. Graphic materials in the operation orders’ annexes were interpreted to specify, confirm or refute the findings, complimentary to textual findings. For example, the enemy’s courses of action overlays were compared to the battalion’s scheme of manoeuvre to identify if the codes of pre-emption, simultaneity and avoiding enemy strengths were manifested in the battle plan. Multiple codings were allowed in case one coding unit depicted ideas about different codes. The students’ assignments were assessed to determine whether the manoeuvre principle was expressed directly (2 points), implied (1 point) or not manifested at all (0 points).

Student Assignments’ Grading; Source: Authors.

What Do we Mean by the Manoeuvrist Approach? The Lecturers’ Perception.

The interviews with three leading lecturers responsible for the Advanced Officer Course revealed that most aspects of the maneuvrist approach theory occurred in their understanding, meaning that the theoretical treatment of topic in the lessons is expected to cover the theme sufficiently. However, the perception varied, whether it is the opposite to war of attrition or not and what are the stressed focal points necessary to teach. The following paragraphs use quotes from lecturers to give more detailed examples of these results.

According to the interviews, the manoeuvrist approach is a mindset, a way of thinking, a philosophy of “how to beat the enemy with minimal resources”,[28], [29] or “a way of fighting that assumes exploiting opportunities, initiative, creating confusion and using up the opponent’s confusion, breaking up the enemy, taking huge risks, causing a mess etc”.[30] However, the perceptions may also vary: either it is “the opposite to the war of attrition”[31] or, it is “…often mistakenly indicated [as such] in several books, for example by Leonhard, or taught in academies, because the opposite to the manoeuvre warfare is rather a methodical warfare”.[32] The interviewees say several examples from the past could be found, starting from the Mongolian era, the Second World War and German rapid risky attacks, the Georgian War or Nagorno-Karabakh, and some events in Ukraine during recent years. This all brought the interviewees to the conclusion that manoeuvre warfare as such is not dead. Still, it is supposed to be rather common sense in the military and definitely needs to be taught.

The manoeuvrist approach is a mindset, a way of thinking, a philosophy of “how to beat the enemy with minimal resources”, or “a way of fighting that assumes exploiting opportunities, initiative, creating confusion and using up the opponent’s confusion, breaking up the enemy, taking huge risks, causing a mess.

Different aspects of manoeuvre warfare were emphasised differently in lecturers’ perceptions, referring to the relative importance or neglect of those aspects of the manoeuvrist approach. Main effort and combined arms were only briefly mentioned: the first one is also referred to as either Schwerpunkt or decisive action, and the second is something that should manifest itself in schemes of manoeuvre. These aspects are taught in theory during the lessons, but the lecturers pointed out that the students would probably truly comprehend their essence only when conducting practical exercises.

Avoiding unnecessary fights was brought out by lecturers as a crucial aspect for the Estonian field grade officers to comprehend when deciding on their command and actions because Estonia is a small country with rather limited military resources against a massive, highly mobile enemy. Avoiding unnecessary fighting was described as avoiding enemy strength, breaking down the enemy’s mentality, and cohesion. Yet, the true meaning of it all needs to be clarified to the students, as it may very often be misunderstood as a choice not to follow orders, while in reality, there could be no option to avoid anything (“if our task is to keep the enemy from crossing Narva River, then what is there to avoid?”[33]).

Mission command as a relevant part of the manoeuvrist approach was addressed by the interviewees in terms of the philosophy of leadership with mutual understanding and trust at the centre of it. Mission command appears to be hard to detect explicitly on papers and orders because it is rather a latent phenomenon manifesting itself in a positive atmosphere and synergy amongst the planning staff and subordinate commanders serving some time, working together. “To make this bunch work together, they need to fight it out, argue, get to results, fail a few times… and maybe the prettiest, honest-to-goodness thing won’t come out after all, but the guy is better than before after it”.[34]

Teaching the Manoeuvrist Approach at the Military Academies – What, How and to Whom?

According to McCoy et al.,[35] the responsibility of manoeuvre warfare can be transitioned to the small unit leaders. The leading lecturers at the EMA stated that the manoeuvrist approach should be taught to all levels of officer courses. Describing it as a pyramid going up, drills are highly important on lower levels, while the manoeuvrist approach is a mindset of bold new ideas and decisive risky actions, growing more important on higher levels. As for Estonia, it came clearly out that we have no other option than to apply the manoeuvrist approach, because “in the attrition warfare we get beaten, in the methodical warfare we will be defeated as well”,[36] “we have no geography nor resources for the attrition warfare”,[37] thus we claim that it needs to be taught as effectively as possible.

We have no geography nor resources for the attrition warfare.

The lecturers considered the commander’s assessment and intent, as well as ways of thinking about how to overcome the enemy the most important aspects of what, and how to teach to attain competence in the manoeuvrist approach. In addition to using compulsory literature and examples from the past, teaching must go beyond the theory – it also needs examples of practical use during exercises. Still, one should exercise caution when considering the use of strict checklists and, concurring with the standpoint of McDoy et al.,[38] because the manoeuvrist approach is based on outwitting the opponent, creating confusion, deception if needed, and taking risks, quickly exploiting the emerged opportunities, and that needs inventiveness and bold decisions.

Methods of teaching the manoeuvrist approach should include case studies from history, solving tactical problems, war games, creating plans according to the commander’s intent and playing it through. There is an important issue about the practical part, games and solving situations – it needs more time and thorough discussion about the reasoning and options. Thus, it needs more staff and mentors to be present and observe throughout the practice. As Matlary brought out, in the U.S. Marine Corps, developing critical thinking by discussing the reasoning behind decisions is also considered important and is used to teach tactics to junior officers.[39]

In the U.S. Marine Corps, developing critical thinking by discussing the reasoning behind decisions is also considered important and is used to teach tactics to junior officers.

As for assessing such competence, the interviewees agreed it is rather complicated, to some extent detectable from adequacy of the intent or schemes based on the commander’s intent, scheme of manoeuvre. However, the most important nuances would manifest themselves subjectively, in the atmosphere of the working environment, in the ways the commander presents his or her intent or solves problems. Thus, it must be considered at the military academies, how to include such subjectively perceived yet crucial aspects among the assessed elements of training, and even more, how to differentiate between sufficient, good and very good presentations of creating such an atmosphere, necessary for building trust, for example.

Assessing the Manifestation of the Manoeuvrist Principles in Students’ Assignments

As suggested by the lecturers, the elements of mission command were challenging to discern. In a few instances, students highlighted the significance of boldness, simplicity and flexibility. However, a comprehensive evaluation of these intrinsic qualities would necessitate the implementation of rigorous wargaming or command exercises. Similarly, the principle of combined arms was largely evident, manifesting as many combinations of effects through indirect fires, engineering, and the cross-attaching subunits of diverse specialities.

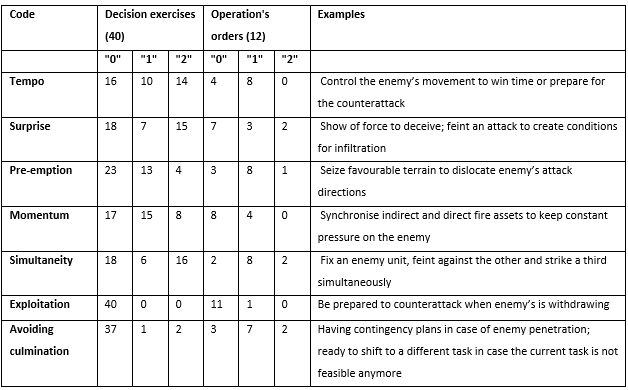

Manifestation of Manoeuvrist Principles–Seizing and holding the Initiative–in Students’ Assignments; Source: Authors.

The significance of the initiative was more evident in the decision exercises. The concept of tempo was primarily operationalised to control the tempo of enemy actions, while momentum served as planning guidance for the staff. The element of surprise was also more prominent in these assignments and was explicitly stated in the assessment and key tasks. It is conceivable that, during the process of staff work, students may lack the requisite experience to effectively apply these principles in the detailed courses of action. It is notable that the exploitation principle is absent from the assignments. In only one instance was the option to capitalise on the enemy’s withdrawal presented, whereas in the others, the end state was limited by the task assigned to the battalion.

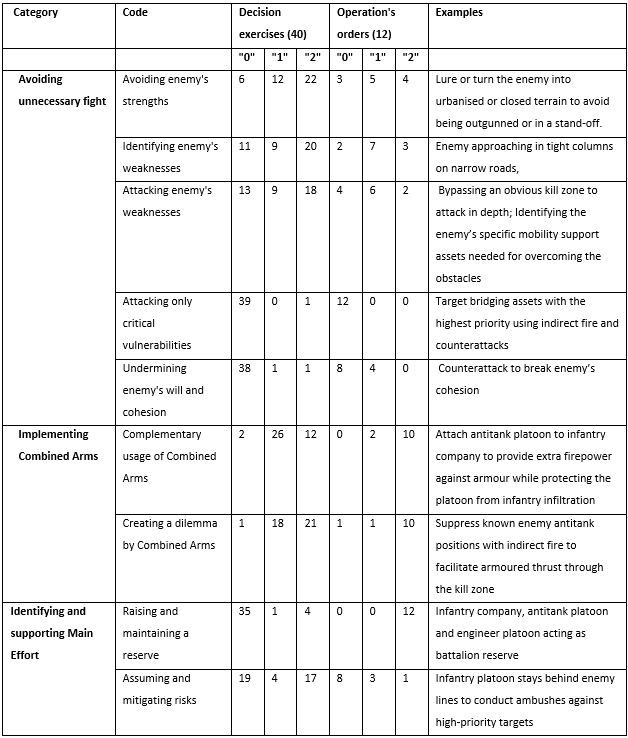

Manifestation of Manoeuvrist Principles in Students’ Assignments; Source: Authors.

In the majority of assignments, the strengths and weaknesses of the opposing forces were identified correctly. However, while the former were avoided successfully, the latter were not commonly targeted. The majority of students (>90%) associated these concepts with utilising appropriate terrain or preventing enemy utilisation through emplacement of obstacles. Therefore, frequently, engineering assets were identified as the enemy’s critical vulnerabilities. Nevertheless, the destruction of these assets was not typically stated as a decisive action, and the responsibility was assigned to combat support units. At the same time, the infantry was tasked with combating the advancing manoeuvre units. Notably, the concept of attacking the enemy on the moral plane by undermining its will was also absent. Two explanations can be given for this phenomenon. Firstly, the student’s knowledge of the enemy is not sufficient, and the 60-minute timeframe allotted for the decision exercise is too short for a comprehensive analysis of the enemy. Secondly, in numerous operation’s orders, other units within the brigade were already tasked with neutralising the critical vulnerabilities, thereby reducing the need to apply this principle.

The principle of the main effort is evident in the construct of decisive action, which was articulated consistently and explicitly in the commander’s intent. The reserve concept was also present in every operations order, yet only manifested in five instances in the decision exercises. In contrast, the concept of tactical risk is more prominent in the latter, serving as an explanation for making the decision. When tactical risk was explicitly articulated (18), it was evident that raising combat power for the main effort was warranted. However, in the operations orders, tasks assigned to the reserve were not directly aligned with supporting the Schwerpunkt, and neither was the reserve’s size and relative combat power sufficient to facilitate exploitation.

The principle of the main effort is evident in the construct of decisive action, which was articulated consistently and explicitly in the commander’s intent.

The analysis of students’ assignments indicated that the manoeuvrist principles were generally adhered to by the students. Still, due to the disparate structures and operation types, the principles, exhibited varying degrees of prominence. While this testifies to the incomparable nature of the tasks, it also suggests that changes in teaching methodology could produce more consistent results for both – more effective teaching of these principles and assessment of the outcome.

The Necessity Remains

Summing up the literature and the perception of the leading lecturers, the necessity of teaching principles of manoeuvrist approach at the military academies remains, especially in the case of unequal power and resources. Thus, to best prepare our officers to apply those principles of manoeuvrist approach, we must come further from the theory, find options for practising both defensive and offensive actions accompanied by competent mentors and deep feedback discussions of reasoning. If we fail in this, we risk having trained a generation of officers who seek to win battles by applying brute force against force, which does not guarantee victory in an unequal balance of power.

If we fail in this, we risk having trained a generation of officers who seek to win battles by applying brute force against force, which does not guarantee victory in an unequal balance of power.

In the students’ assignments, the principle of the combined arms approach was always visible. At the same time, the elements of initiative varied widely, and the aspects of mission command were difficult to detect. In addition to student’s performance, this may be due to the different nature of the missions as well as the structure of the assignments. To improve the appreciation of manoeuvrist principles in the academy, more emphasis should be placed on identifying critical vulnerabilities and influencing the enemy’s will and cohesion. At the same time, risks could be more clearly articulated in operational orders, and the issue of reserve could be expanded in decision exercises to underscore the importance of exploitation.

Major Karl-Erik Kirschbaum holds an MA in Military Leadership from the Estonian Military Academy and is currently a chief lecturer of Infantry Company Tactics. His research has involved Military History, specifically the development of military thought.

Ülle Säälik holds a PhD in Educational Sciences from the University of Tartu and is currently an associate professor at the Estonian Military Academy. Her research focuses on pedagogy and aspects of leadership and educational psychology, focusing on the leader’s identity and role, military morale, and leader development.

Lieutenant Colonel Eero Aija holds an MA in Military Leadership from the Estonian Military Academy. He is a former Commander of the Scouts Battalion and currently leads the Chair of Tactics at the Estonian Military Academy. His research interests include Mission Command.

The views contained in this article are the authors’ alone and do not represent the views of the Estonian Military Academy.

[1] ATP-3.2.1,“Conduct of Land Tactical Operations,“ Edition C, Version 1. (NATO Allied Tactical Publication, 2022), 14.

[2] Idem.

[3] In NATO, manoeuvre units are divided according to their level of armour protection and firepower. The more armoured the vehicles and the more powerful weapon systems the unit encompasses, the heavier it is considered. (NATO Corrigendum Bi-SC Capability Codes and Capability Statements (CC&CS), 2022).

[4] Formation – A common term used to describe a land force’s tactical echelon, normally a division or a brigade.

[5] Unit and sub-unit – A common term used to describe a land forces tactical echelon, normally a unit is considered as a battalion or squadron and a sub-unit is considered as a manoeuvre company or a fire battery.

[6] Neil D. McCoy, Adam D. Duvall, Joshua L. Larson and Luke T. Hudson, “Maneuver Warfare. The way forward,“ Marine Corps Gazette, May 2020.

[7] ADRP 3-0, “Operations” US Army, 2016, 2-2.

[8] The US Army lists four Defeat Mechanism: destroy, dislocate, disintegrate and isolate (US Army ARDP 3-0 Operations, 2016). When comparing the NATO’s definition of ‘disrupt’ and US Army’s ‘disintegrate’, the similarities are well noted. Both aims to attack the enemy’s critical vulnerabilities.

[9] Frank Hoffmann, “Defeat Mechanisms in Modern Warfare,” Parameters 51, no. 4 (2021): 49-66.

[10] UK Land Operations, “Army Doctrine Publication,“ (Land Warfare Development Centre), 5-5.

[11] According to NATO capstone doctrine AJP-01 Allied Joint Doctrine (Ed F Ver 1, 2022), 82.

[12] Eero Aija, “Manööversõja põhimõtete rakendamine Eesti Kaitseväe kergejalaväepataljoni rünnakus,” (Application of the Principles of Manoeuvre Warfare in a Light Infantry Battalion Attack of the Estonian Defence Forces). (MA diss., Estonian Military Academy, 2011).

[13] Idem.

[14] Idem.

[15] ATP-3.2.1,“Conduct of Land Tactical Operations,“ Edition C, Version 1. (NATO Allied Tactical Publication, 2022), 78.

[16] William S. Lind, “The Theory and Practice of Maneuver Warfare. Maneuver Warfare. An Anthology,” (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1993), 9.

[17] William S. Lind, “Maneuver Warfare Handbook” (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1985), 18.

[18] ATP-3.2.2, “Command and Control of Allied Land Forces. Edition B, Version 1,” (NATO Allied Tactical Publication, 2016), 1-7.

[19] Mikael, Weissmann and Niklas Nilsson (eds), “Advanced Land Warfare: Tactics and Operations,” (Oxford, 2023; online edn, Oxford Academic, April 20, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192857422.001.0001, accessed May 06, 2024.

[20] AAP-6, “NATO Glossary of Terms and Definitions,“ 2019.

[21] William S. Lind, “Maneuver Warfare Handbook,” (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1985), 18.

[22] In the context of manoeuvre theory a ’dislocation’ is an action to deny him the ability to bring his strength to bear or to persuade him that his strength is irrelevant.’ ATP-3.2.1, Conduct of Land Tactical Operations. Edition C, Version 1, (NATO Allied Tactical Publication, 2022), 19.

[23] William S. Lind, “Maneuver Warfare Handbook,” (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1985), 20-21.

[24] Robert R. Leonhard, “The Art of Maneuver: Maneuver-Warfare Theory and Air-Land Battle,” (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1991). 91-110.

[25] Idem.

[26] William S. Lind, 1985, Maneuver Warfare Handbook, (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1985).

[27] Eero Aija, “Manööversõja põhimõtete rakendamine Eesti Kaitseväe kergejalaväepataljoni rünnakus,” (Application of the Principles of Manoeuvre Warfare in a Light Infantry Battalion Attack of the Estonian Defence Forces), (MA diss., Estonian Military Academy, 2011).

[28] Interview 1 with a leading lecturer at the Estonian Military Academy, interviewed by the authors, Tartu, June 13, 2024.

[29] Interview 3 with a leading lecturer at the Estonian Military Academy, interviewed by the authors, Tartu, June 21, 2024.

[30] Interview 2 with a former leading lecturer at the Estonian Military Academy, interviewed by the authors, Tartu, June 21, 2024.

[31] Interview 3 with a leading lecturer at the Estonian Military Academy, interviewed by the authors, Tartu, June 21, 2024.

[32] Interview 2 with a former leading lecturer at the Estonian Military Academy, interviewed by the authors, Tartu, June 21, 2024.

[33] Interview 2 with a former leading lecturer at the Estonian Military Academy, interviewed by the authors, Tartu, June 21, 2024.

[34] Interview 2 with a former leading lecturer at the Estonian Military Academy, interviewed by the authors, Tartu, June 21, 2024.

[35] Neil D. McCoy, Adam D. Duvall, Joshua L. Larson and Luke T. Hudson, Maneuver Warfare. The way forward, Marine Corps Gazette, May 2020.

[36] Interview 2 with a former leading lecturer at the Estonian Military Academy, interviewed by the authors, Tartu, June 21, 2024.

[37] Interview 3 with a leading lecturer at the Estonian Military Academy, interviewed by the authors, Tartu, June 21, 2024.

[38] Neil D. McCoy, Adam D. Duvall, Joshua L. Larson and Luke T. Hudson, Maneuver Warfare. The way forward, Marine Corps Gazette, May 2020.

[39] Philip Matlary, ”Teaching tactics as armies integrate. A comparative case study of United States Marine Corps schools and the Norwegian Military Academy,“ (MA diss., King’s College, 2018), 47.