Abstract: The recognition of existential threats such as cognitive warfare is crucial to avoid defeat. Western societies must address such threats by leveraging their militaries’ adaptability. Relying solely on the military poses risks, however, necessitating a comprehensive approach to national security. Coordination among all the instruments of power under democratic control is essential for effective outcomes. Western militaries should focus on deterrence and support political decision making. Cognitive warfare targeting civilians requires continuous societal education and enhanced governmental information capabilities. While international law addresses various challenges, there may not be a legal solution for those arising from cognitive warfare. In the face of modern threats Europe may need to defend its values through comprehensive, coordinated and synchronized means.

Problem statement: How can the military instrument of power be used to counter cognitive warfare?

So what?: The modern state has more than just one instrument of power. Coordinated and synchronized, such instruments can achieve the most effective and efficient outcomes in concertation. The military’s role in this orchestra should be twofold. It must ensure credible deterrence while providing valuable processes, procedures and techniques.

Source: shutterstock.com/UladzimirZuyeu

Unfair game; two approaches

According to Herodotus, when threatened by the Persians with such a multitude of arrows that they obscured the sun during the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC, the Spartan warrior Dienekes responded, “Then we will fight in the shade”.[1] In subsequent centuries several statesmen and philosophers have reattributed and reinterpreted this quotation. Its original meaning has evolved. The original statement underlined the paradoxically advantageous effect of fighting in the shade instead of under the blazing sun.[2] Another possible interpretation was added over the centuries, however: forbearance in clear sight of an overwhelming threat.[3] Confronted by an existential threat, ancient Greece, European culture’s cradle, set the scene for winning a war by seeking an advantage in inferiority or defiant resistance.

More than two thousand years later, Europe again faces an existential threat. Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine is not a mere inter-state conflict at the continent’s eastern edges. It is part of a campaign that seeks to eradicate the Western way of life, the recognized international legal framework, European values and supranational cohesion.[4] To this end, Russia and its partners have long waged a hybrid war against Europe. Unlike the Persian Wars, the weapons are no longer arrows. Disinformation campaigns, information warfare and cognitive warfare endanger social cohesion, transnational solidarity and public support for resistance to the external threat.[5] These means clearly fall below the threshold of armed conflict yet still challenge Western societies.[6] Once the threat is recognized and acknowledged, however, Europe may decide how to fight back by finding the advantage in turmoil or defiant forbearance.

Russia and its partners have long waged a hybrid war against Europe.

No response without recognition

The cornerstone of any response to a threat is its official political recognition. As plain as this sounds, Europe especially still lacks situational awareness. Russia’s military intrusions in Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014 were not followed by international condemnation or isolation.[7] On the contrary, a policy of appeasement and the deepening of economic dependence, especially on fossil energy, led to public ignorance of a painful fact: Russia’s assertiveness was no longer limited to the diplomatic domain. Even the Russian government’s blatant – and unfortunately successful – attempts to “hire” former high-ranking European politicians, including former German chancellor Gerhard Schröder and former French prime minister François Fillon, to gain an even deeper foothold in European political decision making were not taken seriously.[8] Even Russia’s most recent invasion of Ukraine is still not recognized for what it is: a frontal attack on international law and order and European values.

The ongoing attritional warfare in Ukraine is just the most obvious symptom of Russia’s aggression. Beneath this most cruel and visible campaign Russia and its partners are waging a more clandestine war against the West. It is a war for dominance in the information domain, a battle for superiority in attributing and interpreting information.[9] The aim is to shape how societies think about and influence the understanding of past, ongoing and future events and to diminish – if not annihilate – Western societies’ trust and belief in values and their willingness to stand up for them.[10]

Although Western societies’ support for Ukraine is remarkable and has undoubtedly enabled it to resist Russian aggression so far,[11] one might question whether the problem’s entirety is recognized as a threat not only to a country on Europe’s eastern edge but also as an attack on democratic concepts. Meanwhile, funds continue to flow to Ukraine, and weapon systems and ammunition are slowly but steadily being delivered to the East. Most European nations still lag in their energy independence, autonomous military deterrence and social resilience targets.[12] It seems the superstition prevails that the current friction will be over one day, followed by a return to a new normal, with mutual trust, recognition of international law and good order.

Most European nations still lag in their energy independence, autonomous military deterrence and social resilience targets.

Apparently, Russia’s openly belligerent diplomatic, economic and even military threat posture has not (yet) crossed the threshold to be recognized for what it is – an existential threat.[13] Political statements outline the obvious. War does not begin with troop movements, economic blackmail, nuclear brinkmanship, cyberattacks, targeted killings, espionage and obvious human rights violations. It does not begin with strategic bombers and tanks crossing internationally recognized borders.[14] [15] Both the People’s Republic of China’s “Unrestricted Warfare” and Russia’s “Active Measures” clearly illustrate this.[16] Even if Western leaders wish to apply the legally institutionalized definition of war, these endeavours are in vain as long as one side decides no longer to acknowledge them. Clausewitz famously compared war with a wrestling match in which one side tried to compel the other to submit.[17] Cognitive warfare does exactly that. Peace needs the commitment of two sides; war only one. Wars start when political leaders recognize and declare (decide) that a war has started. As inconvenient as this decision appears, even with obvious belligerent deeds, it is more difficult to recognize clandestine acts below the threshold of conventional warfare as acts of war. Yet philosophy is the precursor of reality and the historical example: ignoring the multitude of incoming arrows may avoid a fight but not their deadly effect. The arrows are real, and they are aimed at the West.

Antagonist powers’ attacks occur in the cognitive dimension. Cognitive warfare includes activities synchronized with other instruments of power to affect attitudes and behaviours by influencing, protecting or disrupting individual, group or population-level cognition to gain an advantage over an adversary. Whole-of-society manipulation has become a new norm designed to modify perceptions of reality, with the shaping of human cognition a critical warfare realm.[18] Given this definition, how can the military instrument of power counter or meaningfully support endeavours to counter such warfare? Defiant military forbearance or creativity in ambiguity? Waiting for a military escalation or comprehensive counteraction?

If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail

The term cognitive warfare lends itself to an attribution to the military instrument of power. Ideally, states run a military to wage war or to respond to existential threats. Consequently, if cognitive warfare existentially threatens a state by attacking its social cohesion, delegitimizing its political leadership and even interfering in every democracy’s highest good – elections – military means may be used to counter the threat. Cognitive warfare integrates cyber, information, psychological and social engineering capabilities,[19] all of which are available in the military.

If cognitive warfare existentially threatens a state by attacking its social cohesion, delegitimizing its political leadership and even interfering in every democracy’s highest good – elections – military means may be used to counter the threat.

To solve a problem, most Western militaries follow distinct planning steps. Political objectives are translated to military objectives. These objectives contribute to achieving a defined desired end state. (Decisive) conditions and effects, created by military and complementary non-military actions, define a roadmap for getting from an unacceptable to an acceptable condition.[20]

![Source: COPD[21]](https://tdhj.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Wasinger_02.jpg)

Source: COPD[21]

Undoubtedly, cognitive warfare takes place in a (functional rather than geographical) area of responsibility within a unique operational environment, namely the human mind. Equipment and structures are derived from tasks and tactics. Yet these necessary tactics go beyond the doctrinal and indeed legal limitations of Western militaries. Western military doctrines explicitly exclude their populations from influence operations.[25] Besides, military efforts to shape how nations’ populations think are clearly beyond Western societies’ legal frameworks. Apparently, there is no cognitive warfighting domain;[26] and even if there were, Western militaries would be prohibited from operating in it against their own populations.

Moreover, for such an operational environment, military terminology appears too absolute, too Mahanian. Terms such as supremacy and superiority imply a kind of unchallenged dominance in respective dimensions. In an age of digitalization and connectivity information freely circulates online in accordance with European values. In this context cyberspace is both a means of transmission and a warfighting domain for disinformation, as well as information and cognitive warfare. Cyberspace has essentially facilitated the creation of the vitreous human and – potentially – transparent society. Digitalization and the everyday use of cyberspace have turned this artificial domain into a place of actual consequence, a diplomatic tool, an economic factor, a military effector and a social space satisfying the human need for social connectivity, for example. Cyberspace has contributed to the democritization of information while allowing malign actors to influence target audiences, set and dominate narratives, and exploit information.[27] No absolute supremacy in the cognitive dimension uses mainly democratized cyberspace.

The ongoing war in Ukraine has emphasized the dominance of a more Corbettian approach, meaning the necessity to achieve conditions that are good enough to make the best use of a certain (functional) area for a defined period.[28] This in turn seems achievable in both practical and legal terms, as the aim is neither social indoctrination nor permanent cognitive alignment. It remains questionable, however, whether the military is the most suitable instrument of power to do this.

The ongoing war in Ukraine has emphasized the dominance of a more Corbettian approach, meaning the necessity to achieve conditions that are good enough to make the best use of a certain (functional) area for a defined period.

The military instrument of power is a nation’s executive approach to external threats. This fact clearly distinguishes it from internally oriented police forces.[29] Tasking the military with either waging or countering cognitive warfare seems an obvious but futile choice. Although appropriate planning mechanisms are in place, neither a military’s characteristics nor its democratically legitimized framework and organizational culture as a nation’s existential guardian make it the right tool for the task. Cognitive warfighting brigades will not solve the problem. They would fight in the dark in defiant forbearance, restricted, ill-equipped, inappropriately trained and ultimately without achieving the desired effect.

Advantage in ambiguity

Cognitive warfare must be waged in synchronicity with other instruments of power to affect attitudes and behaviours. Military warfighting domains and dimensions such as cyberspace, the electromagnetic spectrum and the information realm are mere facets of a comprehensive concept. As such, the threats are not only a technical hack. They holistically harm our societies. They undermine democracies by diminishing both people’s trust in politics and their willingness to defend our way of life. They challenge the legal and ethical framework by exploiting Western adherence to the rule of law and liberalism. (More or less) reasonable doubts, alternative truths and plausible deniability target human psychology in the information age. All these endeavours lead to geopolitical shifts that marginalize Europe’s role on the world stage.[30] Holistic challenges call for comprehensive answers! The problem’s solution therefore cannot be found in a single instrument of (hard) power.

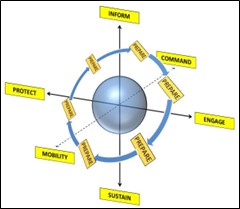

Countering cognitive warfare and effectively responding to it if necessary (and appreciating its relevance for military planning and operations’ execution) is mainly about preparation. All military capability areas – command, engage/operate, sustain, mobility/project, protect and inform – are based on proper preparation. Countering cognitive warfare in the “current” inevitably leads to a struggle for narrative dominance, the “absolute truth” and superior interpretation.[31] Unfortunately, Western societies have had to learn that “factual truth” as such does not matter. Once a narrative dominates the information realm, people’s way of thinking is already shaped. Examples of this phenomenon range from the well-known (but non-existent) promise to Gorbachev concerning the inclusion of former Warsaw Pact states in NATO to Vladimir Putin’s historical (but irrelevant and sometimes even absurd) claims on Ukraine.[32] [33] [34] Subjective truth – and only this matters to the individual – lies in people’s beliefs. “Truth” lies in one’s perception, and war happens when politicians say there is a war, not when tanks cross a border.

Source: Author

Russia has been at war with the West since Vladimir Putin stated this publicly on several occasions, among others during the 2008 Munich Security Conference.[35] It is a war that is still not actively waged with military means outside Ukraine. This should in turn mean that the West is at war too. Political leaders must face this inconvenience and accept it as fact. It is not a war the West chose to wage. It is a war that was imposed on the West, no matter how blatantly Vladimir Putin spins the facts. Western societies should therefore ensure both military deterrence and social resilience in all domains, dimensions and realms, and exploit strategic ambiguity. A society that is well informed about a state of war (especially one that is not waged by military means) is more willing to develop, support and contribute to deterrence and resilience.[36]

Indeed, a huge amount of work remains to be done in fields such as education (e.g. intellectual national defence, national security and defence policy, European values), governmental, semi-governmental and civil economy (strategic autonomy, national stockpiling), society (social cohesion, plurality, inclusivity and diversity management), and information technology (the value and curse of social media, digital literacy). Nevertheless, there is indeed a need for a military contribution. Militaries have developed processes and procedures throughout history that work in the worst imaginable circumstances and still deliver viable solutions.

Democracies have deficiencies in defining strategic objectives.[37] The military is capable of providing procedures to develop and frame achievable objectives.[38] A nation’s sensors are so numerous, and the lines of communication so vast and complex, that achieving situational awareness is demanding. However, militaries have developed concepts to deal with complexity and complications.[39] Relations and connections between and within societies are multi-layered and shaped, among other factors, by history, culture and religion, so it is challenging to obtain and maintain a comprehensive understanding of social interaction.

Nevertheless, militaries have developed techniques to create, within means and capabilities, a comprehensive understanding of relevant actors, their interests, strengths, weaknesses and interconnections, even for out-of-area operations.[40] Through intrinsic need militaries have the ability to frame problems and define efficient approaches, structures, organizations and ultimately viable courses of action. Militaries possess the tools required to define effects and target audiences, assess risks and appropriate mitigating measures, and measure progress while advancing from an unacceptable to an acceptable status. They have all these tools and can provide them to decision makers, even without being the leading instrument of power.

Militaries have developed techniques to create, within means and capabilities, a comprehensive understanding of relevant actors, their interests, strengths, weaknesses and interconnections, even for out-of-area operations.

This is not, of course, a call to reinvigorate militarism. Moreover, when emphasizing the need for political supremacy over the military instrument of power, Carl von Clausewitz explicitly mentioned the sovereign’s need to appreciate the (military) experts’ best advice.[41] When Clausewitz wrote On War, he did so from the perspective of a sovereign who controlled only one instrument of power, the military. We can assume that had they existed, he would have extended his theory to all other instruments of power.

Although a war may be waged with instruments other than the military, the military can offer support in response to non-kinetic/below-threshold threats such as cognitive threats. In doing so, it is indeed vital not to become a militaristic society. Besides military hard power, a crucial element of deterrence is maintaining and even expanding soft power – namely, European values, liberty and diversity.[42] There is nothing antagonist powers fear more than our open liberal democratic system.[43] Liberal democracy disqualifies the foundation of their power apparatus and ultimately delegitimizes their governance. Fighting in the shade allows the exploitation of strategic ambiguity. Necessary preparatory measures can be taken in the shade instead of under the blazing sun.

Fighting in the shade

To solve a problem, one must recognize that there is one in the first place. Ignoring it will inevitably lead to defeat. Once Western societies take that crucial step, political leaders must decide how to address these multidimensional existential threats: by finding the advantage in turmoil or defiant forbearance. Attributing the preparation for any kind of warfare to the nation’s warfighting instrument appears an obvious solution. Leaders should be aware of military adaptability and inherent obedience. This instrument of power will certainly take up the task and live up to it within its means and capabilities. Yet however adaptable we are, there is a risk that the hammer will treat the problem like a nail, especially given the (definitely required) legal restrictions. In forbearance the military would reactively fight with both hands tied behind its back in a dimension that asked for more comprehensiveness.

Fortunately, the modern state has more than just one instrument of power. Coordinated and synchronized, under the control of legitimized democratic leaders they can achieve the most effective and efficient outcomes in concertation. The military’s role in this orchestra should be twofold. On the one hand it must deliver its raison d’être – namely, deterrence. On the other it can provide valuable processes, procedures and techniques to both the political leadership itself and other instruments of power.

The modern state has more than just one instrument of power.

Ultimately, one should bear in mind that cognitive warfare targets mainly civilians, the democratic sovereign. This is not a new phenomenon. About a hundred years ago, when elaborating on air power and military deep operations, Giulio Douhet wrote, “There will be no distinction any longer between soldiers and civilians. The defence on land and sea will no longer serve to protect the country behind them; nor can victory on land or sea protect the people…”[44] Humankind has found a solution to the problem in international law. This does not mean there will be a legal solution to the challenges imposed on the West by cognitive warfare. It is more likely that it will be an impetus to further educate societies or develop governmental information skills. One way or another it seems inevitable that Europe will again have to defend its existence and values by fighting in the shade.

Matthias Wasinger is a colonel (GS) in the Austrian Armed Forces. He holds a Magister in Military Leadership (Theresan Military Academy), a master’s degree in Operational Studies (US Army Command and General Staff College), and a PhD in Interdisciplinary Studies (University of Vienna). He has served both internationally and nationally at all levels of command. He is also the founder and editor-in-chief of The Defence Horizon Journal. He has served at the International Staff/NATO Headquarters in Brussels since 2020. The views expressed in this paper are the author’s alone.

[1] Herodotus, The Histories Book 7: Polymnia (Start Publishing LLC, 2015).

[2] Plutarch, Apophthegmata Laconica (Loeb Classical Library edition, Vol III, 1931).

[3] Valerius Maximus, Factorum et dictorum memorabilium, liber III.

[4] Peter Dickinson, ‘Putin’s Poisonous Anti-Western Ideology Relies Heavily on Projection’, Atlantic Council, 3 July, 2022, accessed 7 March, 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/putins-poisonous-anti-western-ideology-relies-heavily-on-projection/.

[5] Matthias Wasinger, ‘The Highest Form of Freedom and the West’s Best Weapons to Counter Cognitive Warfare’, TDHJ.org, accessed 21 May, 2024, https://tdhj.org/blog/post/freedom-counter-cognitive-warfare/.

[6] Robert Seely, ‘Defining Contemporary Russian Warfare’, The RUSI Journal Volume 162, Issue 1 (2017): https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2017.1301634.

[7] Akaki Dvali, ‘From Appeasement to Accountability – The West’s New Approach Can Save Georgia from Putin’, Newsweek, 19 March, 2024, accessed 11 May, 2024, https://www.newsweek.com/appeasement-accountability-wests-new-approach-can-save-georgia-putin-opinion-1880600.

[8] Hodun, Milosz and Cappelletti, Francesco, eds, Putin’s Europe: Russia’s Influence in European Democracy (ELF, 2023), 176–177.

[9] Geoffrey Roberts, ‘“Now or Never”: The Immediate Origins of Putin’s Preventative War on Ukraine’, Journal of Military and Strategic Studies Volume 22, Issue 2 (2022).

[10] Ian Garner, ‘The West Is Still Oblivious to Russia’s Information War’, Foreign Policy, 2024, accessed 11 May, 2024, https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/03/09/russia-putin-disinformation-propaganda-hybrid-war/.

[11] Congressional Research Service, Russia’s War Against Ukraine: European Union Responses and U.S.-EU Relations (2024), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11897.

[12] Council of the European Union, ‘“If We Want Peace, We Must Prepare for War”’, news release, 19 March, 2024, accessed 11 May, 2024, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2024/03/19/if-we-want-peace-we-must-prepare-for-war/.

[13] Michael P. o. Liechtenstein, ‘Is a Broader European War Imminent?’, GIS, 2024, accessed 11 May, 2024, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/is-european-war-imminent/.

[14] Rosa Brooks, ‘Can There Be War Without Soldiers?’, Foreign Policy, 2016, accessed 11 May, 2024, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/03/15/can-there-be-war-without-soldiers-weapons-cyberwarfare/.

[15] Seth G. Jones, Three Dangerous Men: Russia, China, Iran, and the Rise of Irregular Warfare (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2021), 73–76.

[16] Seth G. Jones, Three Dangerous Men: Russia, China, Iran, and the Rise of Irregular Warfare (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2021).

[17] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. Michael Howard Princeton, NJ [u.a.]: Princeton Univ. Press, 1989, 75.

[18] Allied Command Transformation, Cognitive Warfare (2024), accessed 10 February, 2024, https://www.act.nato.int/activities/cognitive-warfare/.

[19] Idem.

[20] Allied Command Transformation, Comprehensive Operations Planning Directive: COPD INTERIM V2.0, 4–32 – 4–110.

[21] Ibid., 4–53.

[22] Ibid., 4–32 – 4–110.

[23] Everett C. Dolman, ‘Space Is a Warfighting Domain’, ÆTHER: A JOURNAL OF STRATEGY & AIRPOWER 1, Volume 1 (2022): 84, accessed 10 March, 2024, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/AEtherJournal/Journals/Volume-1_Issue-1/11-Dolman.pdf.

[24] Allied Joint Publication-01, AJP-01 (NATO), no. 01, LEX-06.

[25] AJP-3.10, Allied Joint Doctrine for Information Operations (NATO), no. 3.10, 1–2 – 1–10.

[26] Patrick Hofstetter and Flurin Jossen, ‘There Is No Need for a Cognitive Domain’, TDHJ.org, 2 November, 2023, accessed 13 May 2024, https://tdhj.org/blog/post/no-need-cognitive-domain/.

[27] Matthias Wasinger, ‘The Highest Form of Freedom and the West’s Best Weapons to Counter Cognitive Warfare’, TDHJ.org, accessed 21 May, 2024, https://tdhj.org/blog/post/freedom-counter-cognitive-warfare/.

[28] Julian S. Corbett, Some Principles of Maritime Strategy: A Theory of War on the High Seas; Naval Warfare and the Command of Fleets (Adansonia Press, 2018), 71–141.

[29] Matthias Wasinger, ‘Vom Wesen und Wert des Militärischen: Interdisziplinäre Reflexion zum Alleinstellungsmerkmal des Militärischen zwischen Anspruch und Wirklichkeit’ (Dissertation, Faculty of Law, 2017), 54–55.

[30] Matthias Wasinger, ‘The Highest Form of Freedom and the West’s Best Weapons to Counter Cognitive Warfare’, TDHJ.org, accessed 21 May, 2024, https://tdhj.org/blog/post/freedom-counter-cognitive-warfare/.

[31] See for example: Government of Canada, ‘Countering Disinformation with Facts – Russian Invasion of Ukraine’, Government of Canada, https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/issues_development-enjeux_developpement/response_conflict-reponse_conflits/crisis-crises/ukraine-fact-fait.aspx?lang=eng.

[32] Jeff Neal, ‘“There Was No Promise Not to Enlarge NATO” – Harvard Law School’, Harvard Law School, accessed 14 May, 2024, https://hls.harvard.edu/today/there-was-no-promise-not-to-enlarge-nato/.

[33] NATO, ‘NATO – Official Text: Founding Act on Mutual Relations, Cooperation and Security Between NATO and the Russian Federation Signed in Paris, France, 27 May 1997’, accessed 13 May 2024, https://www.nato.int/cps/su/natohq/official_texts_25468.htm.

[34] Government of Canada, ‘Countering Disinformation with Facts – Russian Invasion of Ukraine’, Government of Canada, https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/issues_development-enjeux_developpement/response_conflict-reponse_conflits/crisis-crises/ukraine-fact-fait.aspx?lang=eng.

[35] Nick Fishwick, ‘Putin Has Declared War on the West. It’s Time to Take the Fight to Russia’, The Cipher Brief, 19 February, 2024, accessed 9 May, 2024, https://www.thecipherbrief.com/column_article/putin-has-declared-war-on-the-west-its-time-to-take-the-fight-to-russia.

[36] Michal Onderco, Wolfgang Wagner, and Alexander Sorg, WHO ARE WILLING to FIGHT for THEIR COUNTRY, and WHY? (2024), accessed 7 May, 2024, https://spectator.clingendael.org/en/publication/who-are-willing-fight-their-country-and-why.

[37] Donald J. Stoker, Why America Loses Wars: Limited War and US Strategy from the Korean War to the Present, Revised and updated [edition] (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022), 53–60.

[38] Allied Command Transformation, Comprehensive Operations Planning Directive: COPD INTERIM V2.0, 3–19 – 3–36.

[39] NATO Science and Technology Organization, ‘Visualisation and the Common Operational Picture’, accessed 13 May, 2024.

[40] Allied Command Transformation, Comprehensive Operations Planning Directive: COPD INTERIM V2.0, 4–13 – 4–48.

[41] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, ed. Michael Howard, (Princeton, NJ [u.a.]: Princeton Univ. Press, 1989), 608–609.

[42] Robert Service, The Penguin History of Modern Russia: From Tsarism to the Twenty-First Century, 4th ed. (London, UK: Penguin, 2021), 571–591.

[43] Timothy Frye, Weak Strongman: The Limits of Power in Putin’s Russia (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2021), 12–14.

[44] Giulio Douhet, The Command of the Air, USAF warrior studies Washington, D.C.: Air Force History and Museums Program, 1942, 10.