Abstract: Leader development includes obtaining certain competencies. For more internalised adoption of the officer’s role, it is necessary to raise cadets’ self-awareness and clarify future role expectations so cadets can identify and verify their future role. Several learning activities may help reveal one’s identity and develop such intrapersonal skills to achieve life-long self-directed development of officer competencies. The Estonian Military Academy has researched the use and effect of those activities, and examples of qualitative studies are presented in this article.

Problem statement: How to achieve lifelong, self-directed development of officer competencies and internalised commitment to the officer’s profession?

Bottom-line-up-front: Leader competencies can be developed more efficiently when integrated with a deeper understanding of one’s professional role, thus contributing to internalised commitment to the profession and building a more robust professional identity.

So what?: As a person naturally strives toward clearer self-determination as well as reasoning one’s actions in life, military academies should also promote self-awareness in the light of the officer’s and leader’s role and identity, using self-assessment, analysis, and reflection while clearly communicating the expectations for the role and providing the necessary support.

Source: shutterstock.com/Beautiful landscape

Introduction

Having competent officers committed to their profession, capable and motivated to continue development throughout their career, is probably the dream of every military organisation. Yet, the question of how to achieve this is the subject of investigation among educators and educational scientists. As US Army Major Todd Hertling stated almost a decade ago, “leader development is in need of a jumpstart”.[1] Hertling’s assertion is true, despite the US Army having a very long and thorough leadership development experience.

Beyond knowledge and skills, military education is also expected to form attitudes and build character. Moreover, as military educators, we must prepare our people to take the lead and responsibility for their development. Thus, we should ask ourselves what we can do to help our learners with such challenges for the best preparation in the ever-changing environment.[2] The challenge in the military field is even more difficult as we deal with changing societies and generations. Western democratic societies have turned towards rising individualism and primacy of self-interest, with rights outweighing responsibilities. This situation contradicts the traditional traits and demands of the armed forces; collective nature, obedience to authority, idealism, and altruism as shared values.[3]

The challenge in the military field is even more difficult as we deal with changing societies and generations. Western democratic societies have turned towards rising individualism and primacy of self-interest, with rights outweighing responsibilities.

To achieve a life-long effect, our goal should be towards the “intrinsic … life-long pursuit of expert knowledge” of every learner we work on, because being a leader in its very essence means being in a constant learning and development process as an example and a role model to our followers.[4] To summarise, to be good at supporting the development of our military leaders (as external actions), we must initiate and guide their self-development (actual changes taking place internally).

How military leaders perceive themselves and how they understand their role as a leader may affect not only their work efficiency and relationship with others but also how subordinates see their work and affect both sides’ job satisfaction.[5] Therefore, the aspects of role perception (who I think I must be, what I think I must do, what characteristics I must have) as well as identity (who I think I am, what I do, what characteristics I have) were taken under focused consideration in the Estonian Military Academy while working on the leader development programme. Together with the military leader competency model, both as the extended role description and a framework for assessment, analysis, and development decisions, formulated in 2020, the research on identity and role is expected to contribute to military leader education and thus to the effectiveness of the Estonian Defence Force personnel in general.[6]

Role and Identity – How We Position Ourselves Reflects On Our Professional Success

Identity as a phenomenon is defined as the social positioning of self and others or cognitive schemas defining situations and receiving cues for behaviour.[7],[8] This includes standards of what is expected of a particular role.[9] A role is also defined as a set of expectations tied to a social position that guides people’s attitudes and behaviours. Role identity is a set of internalised meanings of that role or meanings that people attribute to themselves while in a particular role. It is profoundly affected by the widespread notion of a role in the society or the group.[10] To perform well in a role, people need to be aware of its structural features (behaviours to be accomplished) or its expected features (behaviours expected of, prescribed, or proscribed for that role).[11] When considering the professional role, we are talking about work tasks and duties, their success criteria, abilities, attributes, or the qualification needed. Yet, as we can see, it is not only about knowing and understanding the features but also, more importantly, internalising them and identifying ourselves in terms of those features.

Professional identity is a relatively stable set of attributes, beliefs, values, motives, and experiences that people define themselves in a particular professional role as a part of that organisation, which forms over time and enables the person to get an overview of their preferences, talents, and values.[12] Thus, military organisations and their commanders or other relevant figures accompanying the role performer should be able to communicate clearly what they expect of a military leader. The person preparing for or performing in that role shall then have the chance to adapt to it, assess themselves according to those guidelines of role features, and make conscious decisions for learning.

Military organisations and their commanders or other relevant figures accompanying the role performer should be able to communicate clearly what they expect of a military leader.

When a person understands themselves better, they are more self-confident and understand better what is expected of them.[13] As for the role, the person should identify the role standards and compare them with themselves. Identity verification is expected to occur “by making the perceived meanings about himself in the situation (including the role in this situation) correspond to the meanings in his identity standard”.[14]

According to a study by the Norwegian Army, military identity—the degree to which soldiers and officers are motivated and willing to internalise the expressed values and goals of the Armed Forces—can predict both perceived military competence and skills and organisational commitment; notably, operational identity appears as an important predictor of military performance.[15] Therefore, it is crucial to define the nature of the military profession in every military organisation along with the shared values and goals, competencies needed, and mechanisms to help its people internalise them, to identify themselves in these terms.

Military Leader Competencies, Their Development, and Integration Into Identity

Individual military identities are about practices rather than about attributes.[16] Thus, when considering an image of a good military leader, one should (and often does) think of one’s actions, although the character-based approach to leadership is also widespread. It is not that a person’s personality traits are irrelevant, but it seems easier to assess and probable to change one’s behaviour; therefore, a leader’s actions and ability to behave in a certain way are taken into account. In terms of educating or training someone, this is the combination of knowledge, skills, and attitudes formed during the training.

An individual’s self-perception influences how they think, act and set goals for themselves.[17] By acting in a professional role, we mean completing one’s duties, both prescribed and what the person sees as needed for that role. A certain set of competencies is required in order to obtain an officer’s role. These competencies may vary with the position or level of command. A person preparing to take a particular role needs to know the expected behaviour and what knowledge, skills, or attitudes are necessary. It is also essential to recognise and analyse what the individual already knows, and can do, what kind of attitude and motives drive them, and what they need to cope within that role.

Aligned with previous research on leadership and cognisant of social changes in our society as well as organisational needs (in this case, those of the Estonian Defence Forces – EDF), a competence model for military leaders was composed (see Figure 1).[18] The model consists of three dimensions and six competencies: a task-oriented dimension: management and technical/professional competencies; a change-oriented dimension: leadership and conceptual competencies; and a relation-oriented dimension: interpersonal and intrapersonal. This leader competence model is unique due to its simplicity, while most well-known leadership models tend to provide long lists of actions or characteristics and traits hard to comprehend. Yet, the model is also universal, based on leadership theories widely recognised in western cultures. It has a simple stem structure with flexibility as it accepts the variety of competencies for different levels of leadership and different role-specific tasks. Thus, the model’s authors believe it applies beyond Estonia to the countries of similar western democratic societies that strive towards human-centred leadership and value leaders’ self-development throughout their careers.

The model consists of three dimensions and six competencies: a task-oriented dimension: management and technical/professional competencies; a change-oriented dimension: leadership and conceptual competencies; and a relation-oriented dimension: interpersonal and intrapersonal.

![Figure 1. A modified version of the military leader competency model MILTIC[19], dimensions based on Meerits and Kivipõld (2020).[20]](https://tdhj.org/media/0d3ede_e613737514b44b079dbb9a8656f0a008~mv2.jpg)

Figure 1. A modified version of the military leader competency model MILTIC[19], dimensions based on Meerits and Kivipõld (2020).[20]

The MILTIC model is an acronym derived from six main fields of leader competencies: Management, Intrapersonal, Leadership, Interpersonal and Conceptual. It has been tested by several interest groups: officers at platoon, company, and battalion levels, non-commissioned officers, cadets, and master’s degree students at the military academy, as well as conscripts and reserve platoon leader trainees, the results of which are detailed below.

Comparing one’s current self-perception and possible ideal selves may have significant motivational consequences.[21] Thus, good quality feedback on leader competencies with thorough self-analysis and reflection helps improve cadets’ intrapersonal competency. Such behaviour also encourages continual self-development after the studies at the academy and promotes lifelong learning and improvement throughout a career. Thus, it is necessary to raise (future) leaders’ self-consciousness during studies through different developmental activities such as clarification of one’s identity and strengths and weaknesses. Honest and thorough analysis and acknowledgement of strengths and accepting weaknesses are the very essence of the above-described competency model and are key to lifelong development.

Good quality feedback on leader competencies with thorough self-analysis and reflection helps improve cadets’ intrapersonal competency. Such behaviour also encourages continual self-development after the studies at the academy and promotes lifelong learning and improvement throughout a career.

Efficient development is based on the following elements: challenge — a task demanding extra effort; assessment — including self-assessment and that from others (instructors, co-learners, etc.) at the beginning, during, and after the process or event to offer experience; and support — the environment, in general, being supportive, tolerating mistakes as learning opportunities, instructions with clear criteria and so on.[22] Based on the above, we can see that a leader’s competencies (knowledge, skills and attitudes) can be developed more efficiently when integrated with deeper self-determination, an understanding of one’s professional role, and clarification of its duties and demands, thus contributing to the internal commitment to the profession and building a stronger professional identity.

To sum up, for internal and thus more permanent adoption of the officer’s role, it is necessary to raise cadets’ self-awareness and clarify future role expectations. In this way, cadets can identify and verify the role. Such changes do not occur alone but only when supported with regular guidance provided by mentors, orchestrated challenges prepared by teaching staff, and followed by an honest and systematic self-analysis by cadets after accomplishing such learning challenges.[23] Such an approach demands comprehensive changes and implementation of new practices adopted by a wide range of educators at different levels of military education and should not be done hastily. The educators need to comprehend and believe in the principles as well as be able to apply the appropriate educational tasks. In addition, the whole academic environment needs to be aligned accordingly, providing challenges, assessments, and support throughout the training processes. The effect of the measures still needs to be proven.

The following section presents proof and considerations of what and how to use military education to achieve the above-mentioned self-development goals. The development programme and research studies are still ongoing; thus, the presented ideas and interim conclusions should be considered with caution and are not to be generalised yet.

Research Results and Implementation of the Aspects of Role, Identity, and Competencies into Training Practice

Several studies at the Estonian Military Academy have revealed the interrelatedness of those aspects—competencies, role, and identity—in military leader development, indicating related issues and showing how such a consistent and integrated approach can help officer candidates to comprehend and adopt their future role and verify their officer identity. This section presents examples of qualitative studies to illustrate and demonstrate how military academies and defence forces may gain from thorough work on their personnel’s role perceptions, self-analyses, and -development.

NCOs’ Self-Perception Through the Prism of Competencies

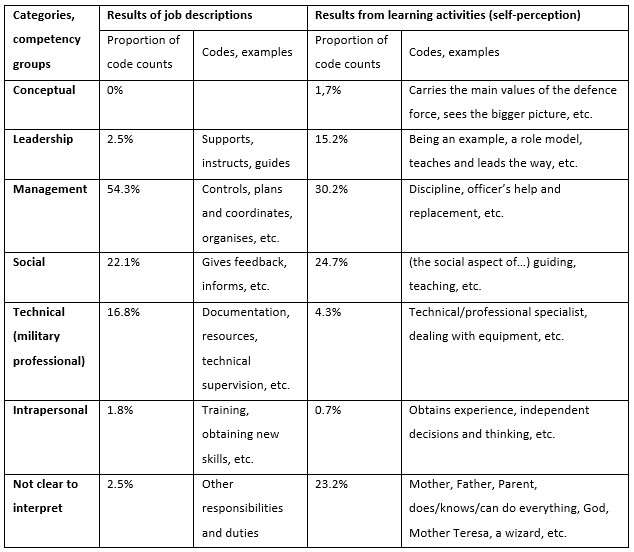

A qualitative study of non-commissioned officers’ self-perception of their role and demands for their role and competencies, as described in job descriptions, revealed that there are several indications of role conflict and problems due to role ambiguity or overload potentially affecting the NCOs’ work and well-being. A random sample of NCOs’ job descriptions was analysed and compared to the results of a learning activity collected during 2019–2021 in follow-up training courses. The activity asked participants to describe the role of an NCO (who an NCO is, what an NCO does, must do, or is expected to do).[24]

The study revealed discrepancies between the officially stated role expectations and the self-perceived understanding of their role as NCOs. For example, the cross-case deductive content analysis showed some imbalance between the competencies needed for duties when the official and self-perceived demands were compared (see table 1).[25] We can see that the official role description stresses management (54.3%). At the same time, self-perception seems to be divided between management, social and leadership competencies and leaves a relatively large proportion to utterances not interpretable by competencies. The latter includes rather dramatic exaggerations such as “an NCO must be a God”, “…an all-knowing wizard”, “must do everything”, “a mother to the conscripts”, “like Mother Teresa”, or “a magician”. Between these role ambiguity issues, no clear expectations communicated, and the feeling of overwhelming workload, the situation seems to be worrying. It hints at the possibility of work-related stress or even burnout.[26]

Self-perception seems to be divided between management, social and leadership competencies and leaves a relatively large proportion to utterances not interpretable by competencies.

Table 1. The qualitative content analysis results comparing the official and self-perceived role descriptions according to the competency groups (Otsus, Säälik, 2021).

The study of NCOs’ self-perception showed how the perceived and officially-stated role behaviours might differ and how identifying oneself in that role may reveal work stress and a feeling of overload or expectation towards that role being too high to fulfil. When the perceived need for competencies diverges from what the role description states and is probably not taught or developed during training, we cannot expect the people in that role to perform very well or enjoy well-being and work satisfaction. There is a need for more specific research on the concurrence of competencies involved in training and those needed for fulfilling one’s role.

Officers’ Identity, Role Perception, and Work-Related Strains

The study of officers’ identity, role perceptions, and potential role conflicts revealed some indications of imbalance in personal and professional roles, possibly causing work-related stress and role conflicts. A qualitative research strategy was applied with data collection based on learning activity, a questionnaire during master’s degree studies at the academy, and follow-up interviews. In 2020–2021 experienced junior grade officers (mainly captains) first completed a learning activity about identity and role perception and self-analysis of one’s characteristics, strengths, and weaknesses and further goals for self-development. Later in 2022, they were asked to participate in interviews. Participation in the survey was strictly voluntary, and the whole study process followed the ethics requirements stated by the grant of the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Tartu (No 337/T-3).[27]

Both personal roles (e.g., father, husband) and professional roles (e.g., officer, leader, soldier) appeared in the self-perceptions of roles and identity. Yet, personal roles took a higher hierarchy of importance than professional ones (see Figure 2). There were several indications of role conflict and work-related strain. The interviewees found that their work-home commitment was off balance. The author identified the most critical components of professional identity development: openness to formal and informal communication (including reflection), supportive community (including commanders), and professional socialisation. The study also found that current annual attestations can potentially serve as a tool to develop officers’ professional identity, but not at the moment. In general, the study demonstrated that officers see their heavy workload as a pervasive problem in their overall well-being and professional identity development.[28]

There were several indications of role conflict and work-related strain. The interviewees found that their work-home commitment was off balance.

![Figure 2. Examples of officers’ roles and their relative importance (Möller, 2022)[29], based on role categories of collective identity by Ehala (2018).[30]](https://tdhj.org/media/0d3ede_a0804efafe244e5aae7a742dd378db98~mv2.jpg)

Figure 2. Examples of officers’ roles and their relative importance (Möller, 2022)[29], based on role categories of collective identity by Ehala (2018).[30]

The sample group’s junior officers (mainly captains) had family responsibilities and approximately 10–15 years of military experience. Whether the same patterns might appear among the young officers (lieutenants as platoon leaders) only starting their career has not been researched yet. In addition, the possible influence of age or generation affecting either individualistic or collectivistic values being ‘me’ rather than ‘us’ may need our attention.

Interpretation of and Comparison with the Military Leader’s Role Through the Prism of Leader Competencies As Seen by the Reserve Platoon Leader Trainees

Service in the Estonian Defence Force is based on conscription; every year, some conscripts are trained to be squad leaders or reserve platoon leaders. During a reserve platoon leader training course in 2020, 90 conscripts were asked to complete a learning task about identity followed by self-analysis, including strengths and weaknesses related to their future role as military leaders. The pre-course and post-course self-analyses were studied using a qualitative content analysis based on the competence model. Participation was voluntary, and the data were processed anonymously without affecting the trainee.

During a reserve platoon leader training course in 2020, 90 conscripts were asked to complete a learning task about identity followed by self-analysis, including strengths and weaknesses related to their future role as military leaders. The pre-course and post-course self-analyses were studied using a qualitative content analysis based on the competence model.

The results of the qualitative content analysis revealed some significant differences in the military leader role perceptions seen through the prism of one’s competencies. First seen as management mostly being done using communication skills (interpersonal competency), the follow-up analysis mostly presented ideas of intrapersonal competency needed for coping well in the role of a platoon leader. However, the course mainly consisted of technical and management issues with a small proportion of leadership skills, slightly introducing some reflection and self-analysis. The results of the content analysis are shown in table 2.[31]

![Table 2. The perception of a military leader’s role from reserve platoon leader trainees, comparing code-count competencies according to the content analysis of pre-course and post-course self-analyses.[32]](https://tdhj.org/media/0d3ede_61ed52cd43334f17a0bc75529adf364d~mv2.jpg)

Table 2. The perception of a military leader’s role from reserve platoon leader trainees, comparing code-count competencies according to the content analysis of pre-course and post-course self-analyses.[32]

At the beginning of the course, the descriptions of leader competencies were expressed in plain terms of common knowledge about command or leadership (e.g., plans activities precisely and quickly, ensuring that the unit “works like clockwork”). In contrast, at the end of the course, more personal and lively descriptions referred to deeper understanding and even concerned inner searches. For example, the course participants have stated that “…even if I happen to decide to be lazy and let the others do the hard work–soon it starts eating me from inside, then the feeling of shame that I let others do what I could do as well…”, or “All this ‘bossing around’ has made me more self-confident, but also critical… useful for further self-development…”.

The change in the level of role description specification occurred as expected; this means that the organisation had delivered the meanings related to that reserve platoon leader’s role during the course and that indications of role verification had taken place. In addition, some conformation of how the group members interpret the role appeared. According to Stets and Serpe (2013), “the conformation of the group’s interpretations as group members perceive situations similarly,” and this is considered useful for the internalisation of the role and alignment with the organisation to which the role belongs.[33]

The change in the level of role description specification occurred as expected; this means that the organisation had delivered the meanings related to that reserve platoon leader’s role during the course and that indications of role verification had taken place.

In addition, some tension and insecurity appeared in post-course self-analyses; a lot of worries and weaknesses came out regarding decision making (“I’m afraid I’ll freeze when I have to make the decision…”) or relationships with others (“how am I going to tell my comrades in the unit what to do?! Only a month ago I was the same conscript…” or “am I going to be accepted by the officers as a leader or commander, if in fact, I am not?”). When young officers lack formal power and inner security, they may seek to compensate for this by publicly behaving in an over-distanced way toward the soldiers, which means that their professional identity as military officers is weakened.[34] In addition, signs of identity conflict or negotiation between two identities were noticed — a perceived intrapersonal tension, discrepancy, or interference between at least two identities — me as civilian or military personnel, and me as soldier/conscript or leader.[35]

Adaptation of Curricula and Learning Tasks in the Estonian Military Academy

When the first attempts at identity clarification and self-analysis tasks were made in 2019–2020, using a learning activity describing self-image, including one’s strengths and weaknesses, feedback from the learners differed rather drastically. Some found it eye-opening, while others refused to write down any weaknesses, stating that “we are military, and militaries do not have any weaknesses” or “How do you expect a leader to reveal his weaknesses?! It demeans him in the eyes of his subordinates!” Others were “surprised after the sessions, teaching of reflection and thorough self-analysis, that it actually truly revealed some aspects that had been either hidden or unknown” to the participant. Those statements led us to the idea of a need for change in the perception of leadership in the military — traditional ‘tough guy’ versus authentic contemporary leader. The new psychology of leadership sets shared social identity at the centre of leadership issues that initiates the followers’ willingness to act in pursuing shared goals.[36] As stated by Northouse, authentic leadership, as one of the newest conceptions in this field, places a strong emphasis on leaders’ intrapersonal skilfulness and developmental perspective, with relational transparency and trust as drivers for followers to act and thrive at work, as well as for the leader to analyse themselves to continue improving in their role.[37] And that is what we should strive for.

As stated earlier, efficient development needs challenge, assessment, and support.[38] Therefore, it is necessary to design training so that those elements appear in formal training and informal occasions such as mentor discussions, etc. While developing the new curricula at the Estonian Military Academy in 2021, leader competency development and self-analysis aspects were added to the aims and learning outcomes. Furthermore, certain self-assessment and reflection tasks were put into practice. These reflection tasks will be kept at the forefront of the cadets’ minds throughout their studies. The objective is to end up with a summative presentation of values, beliefs, strengths, and weaknesses as an officer and a military leader. This process needs more research, as early attempts show it is not easy for many to obtain intrapersonal skillfulness in searching for evidence about themselves. Even if one can do this, one must process and analyse their insights to make conscientious decisions about their development. Such decisions relate to which knowledge or skills still need improvement or what kind of attitude, values or motives either support or hinder role-taking in this organisation. Thus, we must work on individual skills and promote a more general belief in this approach among the people of the EDF. At the same time, we must follow and research its effect and continue to work on the concept as well as tools and measures.

Conclusions

There are indications of how understanding a military leader’s role, assessing leader competencies, clarifying one’s identity, and comparing it to the leader’s role are interrelated. Helping learners at military academies must move towards a more intrinsic change and encourage learners to take responsibility for their own development. Thus, specific training tasks should include clarification of self-perception and a comparison to the expected traits of the future role communicated by the organisation and educators.

The learners at different levels of military training have expressed doubts and worries at first, but also surprise and admittance to the usefulness of the proposed competency assessment tools for reflection and self-analysis tasks during their courses. Indicating a lack of self-confidence and intrapersonal skill that needs to be addressed during training, it also hints that the military environment may not be the safest environment where making mistakes or accepting weaknesses is seen as a normality, and that attitude needs to change. As the tool based on the MILTIC model has been tested on different levels of leaders with different roles, it has proved universally useful for self-development across the military leader’s career levels. Considering that the Estonian Defence Forces are somewhat similar to many others and that they continuously align practices with NATO, our leader development practices are also expected to be usable for other countries. Whether there should be level-specific or role-specific model adaptations for more precise assessment still needs to be studied.

A military leader role model is needed, which would be simple enough to comprehend at different levels (conscripts, cadets, students, officers, etc.). It could be used for guidance during studies, as a tool for self-assessment, for giving feedback to colleagues and peers, and between the leader and subordinates. Yet, this should be evidence-based and scientific—based on the most recent studies in the field and adjusted to the respective organisation, its environment, and society. The concept of the military leader’s role, including its necessary competencies, would benefit from collaboration and agreements from both within the military and outside of it with related parties, just like a doctrine in the Norwegian army.[39]

A military leader role model is needed, which would be simple enough to comprehend at different levels. It could be used for guidance during studies, as a tool for self-assessment, for giving feedback to colleagues and peers, and between the leader and subordinates.

In conclusion, to achieve lifelong self-directed development of an officer’s competencies and internal commitment to the officer profession, military academies must include goals and tasks in training that focus on self-awareness and promote a safe learning environment. Furthermore, it must be tolerant of mistakes and guide learners to exploit both success and failure for the sake of development as a habit and a skill. Also, the organisation can help clarify the officer’s and leader’s roles and identities by working on its concept and clearly communicating the expectations for the role while providing the necessary support throughout training events and an entire career.

Ülle Säälik (PhD, Educational Sciences) is a Lecturer-Field Lead at the Estonian Military Academy. Her research interests include educational psychology, leader development, and morale. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of the Estonian Military Academy.

[1] Todd Hertling, “The Officership Model: Exporting Leader Development to the Force,” Military review 93 (2013): 33.

[2] Wendy Darr and Elliot Loh, An Introduction to Advance in Military Personnel Selection, “Advances in Military Personnel Selection,” NATO STO Technical Report TR-HFM-290 (May 2022): 1-1.

[3] Rino B. Johansen, Jon C. Laberg and Monica Martinussen, „Military Identity as Predictor of Perceived Military Competence and Skills,“ Armed Forces and Society Vol. 40(3) (2014), 521-543.

[4] Center for the Army Profession and Ethic [CAPE], An Army White Paper: The Profession of Arms (2010), 2.

[5] Leonard Karakowsky, Nadia C. DeGama and Kenneth McBey, “Facilitating the Pygmalion effect: The overlooked role of subordinate perceptions of the leader,” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 85 (2012): 579-599. Lindsay M. Mallick, Mary M. Mitchell, Amy Millikan-Bell and M. Shayne Gallaway, “Small Unit Leader Perceptions of Managing Soldier Behavioral Health and Associated Factors,” Military Psychology, 28:3 (2016), 147-161.

[6] Ülle Säälik, Aarne Ermus, Ivar Männamaa, Liisi Toom and Antek Kasemaa, Kaitseväelise juhi pädevusmudel (In Estonian. Military leader competency model). Sõjateadlane/ Estonian Journal of Military Studies, 14 (2020): 11−38.

[7] Sheldon Stryker and Peter J. Burke, “The Past, Present, and Future of an Identity Theory,” Social Psychology Quarterly 63, no. 4 (2000): 284–97.

[8] Mary Bucholtz and Kira Hall, “Identity and Interaction: A Sociocultural Linguistic Approach,” Discourse Studies 7, no. 4–5 (October 2005): 585–614.

[9] Robert B Ewen, An Introduction to Theories of Personality, 4th edition (New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaub Associates, Publishers, 1993).

[10] Ronald L. Jackson (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Identity, Vol. 2. (SAGE Publications Inc., 2010): 648.

[11] Peter J. Burke and Jan E. Stets, Identity Theory, (Oxford University Press, 2009).

[12] Ibarra, Herminia, “Provisional Selves: Experimenting with Image and Identity in Professional Adaptation,” Administrative Science Quarterly 44, no. 4 (1999): 764–91.

[13] Jüri Allik, Anu Realo and Ken Konstabel, Isiksuse psühholoogia (The psychology of personality), (Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus, 2003): 227–250.

[14] Robert B. Ewen, An Introduction to Theories of Personality, 4th edition. (New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaub Associates, Publishers, 1993): 68–69.

[15] Rino B. Johansen, Jon C. Laberg and Monica Martinussen, “Military Identity as Predictor of Perceived Military Competence and Skills,“ Armed Forces and Society Vol. 40(3) (2014), 521–543.

[16] ibid,

[17] Mark R Leary and June Price Tangney, Handbook of Self and Identity, (New York; London: Guilford Press, 2012), 3–14.

[18] Ülle Säälik, Aarne Ermus, Ivar Männamaa, Liisi Toom and Antek Kasemaa, Kaitseväelise juhi pädevusmudel (In Estonian. Military leader competency model). Sõjateadlane/ Estonian Journal of Military Studies, 14 (2020): 11−38.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Artur Meerits and Kurmet Kivipõld, Leadership competencies of first-level military leaders, Leadership & Organization Development Journal, Vol. 41, No. 8 (2020), 953–970.

[21] Daan van Knippenberg, Barbara van Knippenberg, David De Cremer and Michael A. Hogg, “Leadership, self, and identity: A review and research agenda,” Leadership Quarterly 15 (2004): 825–856.

[22] Cynthia D. McCauley, Ellen Van Velsor and Marian N. Ruderman, “Introduction: Our View of Leadership Development,” The Center for Creative Leadership Handbook of Leadership Development, (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2004).

[23] David V. Day, Stephen J. Zaccaro and Stanley M. Halpin, Leader Development for Transforming Organizations: Growing Leaders for Tomorrow, (Mahwah N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2004).

[24] Tanel Otsus and Ülle Säälik, “Rollikonflikt ja rolli hägusus veeblite rollikäsitluses“ (Role conflict and role ambiguity in the NCOs’ role conception). Academia Militaris 3 (2021), 44–46.

[25] Ibid,

[26] Ibid.

[27] Marek Möller, “Ohvitseri professionaalne identiteet ja rollikonflikt“ (In Estonian. Officer’s Professional Identity and Role Conflict), Master’s thesis, (The Estonian Military Academy, 2022).

[28] Ibid,

[29] Ibid,

[30] Martin Ehala, Identiteedimärgid. Ühtekuuluvuse anatoomia, (Signs of identity. The anatomy of esprit de corps.) (Tallinn: Künnimees OÜ, 2018): 120–121.

[31] Ülle Säälik and Antek Kasemaa, ”The reserve platoon leader’s perceptions of their role: critical leader’s competencies,“ (Unpublished manuscript, 2022).

[32] Ibid,

[33] Jan E. Stets and Richard T. Serpe, “Identity Theory,” In: J. DeLamater & A. Ward, Handbook of Social Psychology, (Springer Netherlands, 2013).

[34] Gerry Larsson, Paul T. Bartone, Miepke Bos-Bakx, Erna Danielsson, Ljubica Jelušič, Eva Johansson, Rene Moelker, Misa Sjöberg, Aida Vrbanjac, Jocelyn V. Bartone, George B. Forsythe, Andreas D. Prüfert and Mariusz Wachowicz, “Leader Development in Natural Context: A Grounded Theory Approach to Discovering How Military Leaders Grow,” Military Psychology 18 (2006): S69 – S81.

[35] Janelle M. Jones, and Michaela Hynie, “Similarly Torn, Differentially Shorn? The Experience and Management of Conflict between Multiple Roles, Relationships, and Social Categories,” Frontiers in Psychology 8 (2017): n. pag.

[36] Alexander Haslam, Stephen D. Reicher and Michael J. Platow, The New Psychology of Leadership. Identity, Influence and Power, (London and New York: Routledge, 2020).

[37] Peter G. Northouse, Leadership: theory and practice, 9th edition, (Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publishing, 2022).

[38] Cynthia D. McCauley, Ellen Van Velsor and Marian N. Ruderman, “Introduction: Our View of Leadership Development,” The Center for Creative Leadership Handbook of Leadership Development, (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2004).

[39] Michael D. Johnson, Frederick P. Morgeson, Daniel R. Ilgen, Christopher J. Meyer, and James W. Lloyd. “Multiple Professional Identities: Examining Differences in Identification Across Work-Related Targets.” Journal of Applied Psychology 91 (2) (2006): 498–506.