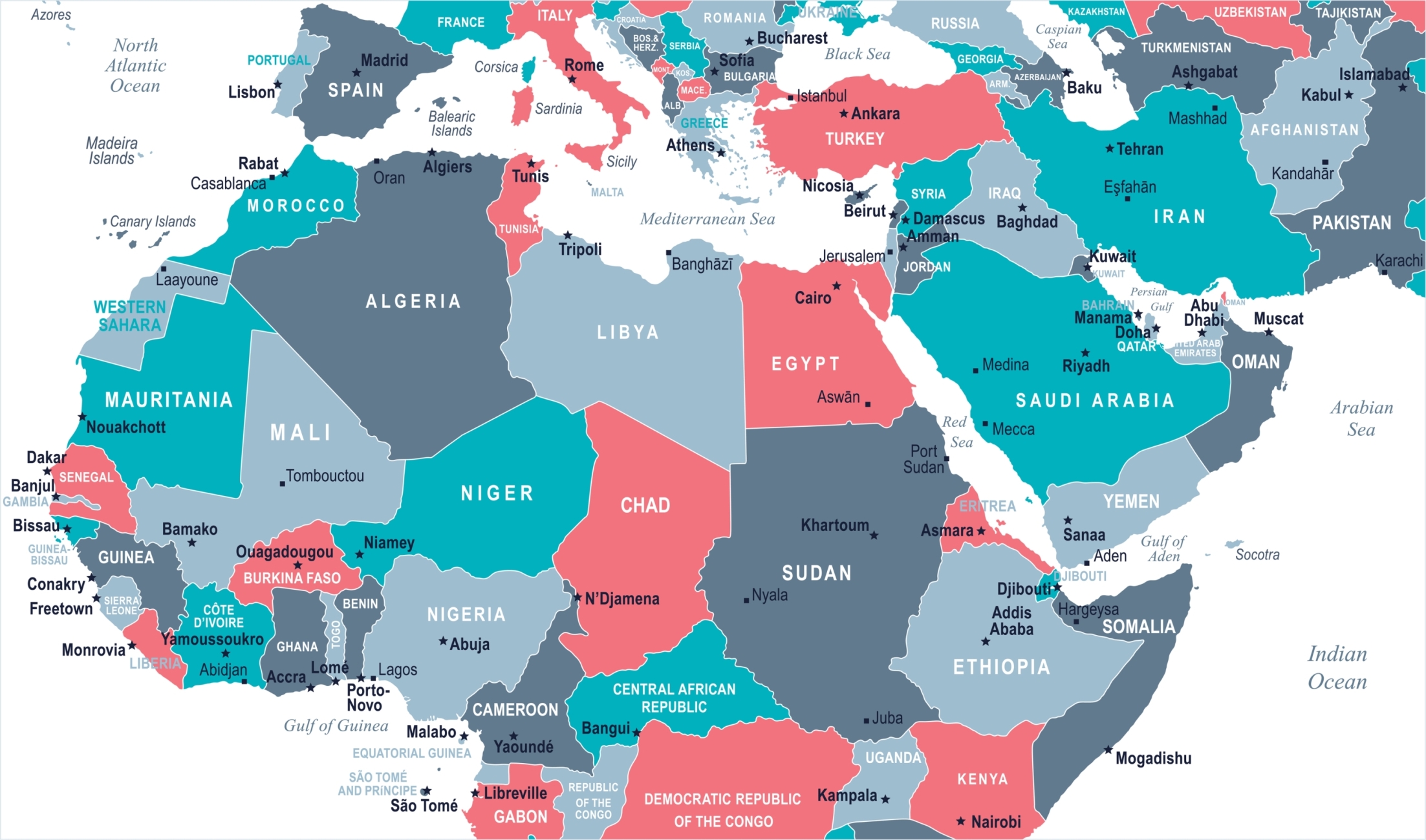

Abstract: In the last two decades, Africans have not only had to contend with the influence of traditionally dominant European states and the United States but also a rising number of emerging and resuscitated powers that seek to take advantage of abundant resources. China, Brazil, India, Israel, Russia, Turkey, and many Gulf States have shown interest in establishing their presence on the continent. Of particular interest are the significant moves made by China, India, Russia and Turkey on the continent. While much of the target of these states is concentrated on natural resource exploitation and trade, their presence has elicited concerns about the return of strongman politics to the continent. Thus, the fear is that the strongman leadership exhibited by leaders in these states will influence the kind of leadership African leaders to engage with them to provide in their respective countries. The effects of hardline leadership that result from these contacts on citizens, internal politics, regional politics and democratic governance could be consequential for the continent.

Problem statement: How can Africa comprehend the presence of emerging powers and its ramification on the disposition of leaders regarding human rights, and domestic and regional politics?

Bottom-line-up-front: China, India, Russia and Turkey have focused on Africa. These are states led by leaders who have tight control of their home states. Xi Jinping, Narendra Modi, Vladimir Putin and Recep Tayyip Erdogan exhibit what has been described as authoritarian and personalized leadership which could threaten volatile democracies in Africa as their counterparts in the continent engage with them. African states may exercise caution in these relationships.

So what?: African states are significantly vulnerable in their relations with these four states. The near-unconditional sale of weapons, provision of soft credit and significant soft power projection by these states to relatively weak African states compound such vulnerabilities. It is imperative to define the rules of engagement and prioritize the national interest above the interest of individual leaders in safeguarding democratic gains. To mitigate adverse external influences, states must consider establishing multilateral protocols through regional and sub-regional organizations that guide engagements with these powers.

The New Euro-Asian Interest in Africa and the Revival of Authoritarianism

Download PDF • 1.21MB

Source: shutterstock.com/Oleg Elkov

Africa and its Resources

With many pundits in fields ranging from economics to politics and security labelling Africa as a continent that will see a phenomenal rise in the 21st century, many international powers have set their eyes on it and its resources. These powers have either had ties to the continent for many decades or have renewed their interests and revamped their foothold. The abundant resources of Africa, despite centuries of heavy exploitation, make such advances towards it hardly surprising: Rare metals important to the global technology industry; huge oil deposits and prospects for more discoveries; a rapidly growing younger population with its consequential market, and youth receiving and exposed to better education characterize the continent’s strengths.

Despite the continent’s longtime ties to and influence from Europe and Asia, the recent and renewed interest shown by Russia, China, Turkey, and India has been viewed with skepticism by analysts who see such interests as threats to democratic gains on the continent. This narrative has been informed by multifaced factors, critical among which are the influence of these external powers on leadership, geopolitics and human rights across the continent. In demystifying the presence of these established and emerging powers and their effects on African leadership, the interlink of politics, (security) and economics that drive these interests need further dissection.

Despite the continent’s longtime ties to and influence from Europe and Asia, the recent and renewed interest shown by Russia, China, Turkey, and India has been viewed with skepticism by analysts who see such interests as threats to democratic gains on the continent.

Theoretically, much of what regulates the relationship between these states falls under realism. The idea that the state is the most important actor is dominant in Africa’s recent contact with these states. As a corollary, state actors, the most consequential of which are the continent’s political leaders, shape these relations. Admittedly, these relations have sometimes featured non-state agencies from these emerging powers that interact with counterpart-agencies in African states in providing services in the area of “low politics”. However, it would appear that the activities of these agencies are part of the larger strategies of home states in advancing the national interest. Thus, the agencies help advance the soft power of home states. Essentially, therefore, realism is the overriding theory in this context. This explains how the relations and interactions between these states and Africa have consequences on state actors and the state itself.

The Post-Soviet Struggle

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, all investments in security and politics by the Soviet Union in Africa came to naught—the successor states could not derive much from it. The ideological war of decades saw the USSR intervene and engage African states and political actors had ended rather abruptly. Russia, the main successor state, became embroiled in its internal affairs and centrifugal forces, so the continent was the least of its worries. For over a decade, Russia showed little interest in the continent as US hegemony had translated into pronounced Western influence and presence on the continent. Washington DC had comfortable leverage across the continent with France, the United Kingdom, and other Western countries. However, since 2000, Russia, led by strongman and longtime ruler Vladimir Putin has renewed its interest in the continent. As late as September 2021, Mali made its intention known to the world about replacing French forces with Russian ‘private’ ones — something unthinkable half a decade ago.[1] The new military junta in Mali consider Putin a reliable partner. Russian private security contractors are already in the Central African Republic in a rare peace effort in the region.

For over a decade, Russia showed little interest in the continent as US hegemony had translated into pronounced Western influence and presence on the continent.

Russian Influence

In recent years, Russia’s bouts of ‘shuttle diplomacy’ have further given a clearer picture of the European power’s agenda on the continent. Top defense and diplomatic officials in Moscow, including Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, have made stops in some African states, cut arms and mining deals, or exchanged assurances of future cooperation. This has been partly catalyzed by well-established Soviet connections on the continent which have been revived.[2] Russian mining companies and arms corporations have landed good deals on the continent in the process. In the spate of 9 years between 2010 and 2019, the number of African countries receiving Russian arms had increased from 16 to 21.[3] Countries like Angola, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Namibia, Central Africa Republic and currently Mali are among the states the Russian Federation has paid particular attention to. Other countries, including Ghana, Guinea and Egypt, have not been ignored. Algeria, in particular, has been a long time Russian partner and remains the largest arms recipient in Africa. This renewed interest by Russia has unnerved both European and American interests in the region. While some have considered the Russian presence as more of an overblown occurrence, the mere fact has drawn attention the world over.[4] The consternation of some has been Russia’s role in Ukraine in 2014 and how it has turned towards Africa after western sanctions. How does Putin’s leadership style influence his counterparts on the continent in the future?

Countries like Angola, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Namibia, Central Africa Republic and currently Mali are among the states the Russian Federation has paid particular attention to.

Source: shutterstock.com/Porcupen

Turkey in Africa

Turkey was the ‘Sick Man of Europe’ before the first World War. After, its Ottoman Empire crumbled helplessly, with several nation-states emerging from it. Subsequently, the former great power had become more of an item in Cold War politics as nationalists assumed political control. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Turkey has sought to pursue an independent foreign policy that has not been all positive. However, its current approach to Africa under the Justice and Development Party (AKP) and Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been significant and worth examining.

Between 2003 and 2021, Turkey had established over 25 embassies across Africa on the diplomatic front. These included troubled Sahel states in West Africa and Chad. During the same period, foreign direct investment by Ankara on the continent had moved from 100 million to 6.5 billion US dollars.[5] The Euro-Asian state has also made substantial strides with its soft power. With the AKP being an Islamist party, Turkey has shown interest and sponsored Mosques and granted scholarships to targeted populations. For example, the Islamic community in Ghana has received a multimillion-dollar Ottoman-inspired National Mosque.[6] Like Russia, Turkey is also promoting its arms industry in Africa. While the country’s arms industry is relatively smaller, the state has made its promotion of foreign policy a priority.

Like Russia, Turkey is also promoting its arms industry in Africa. While the country’s arms industry is relatively smaller, the state has made its promotion of foreign policy a priority.

African states, including Burkina Faso, Chad, Ghana, Mauritania, Senegal, Nigeria, and Rwanda, have recently bought military wares from Turkey. Kenya is reported to have ordered over 100 armored vehicles. Turkish military facilities in Somalia and Libya train security forces in the volatile environments. The country sees itself as a growing power that is geographically not far from Africa. It seeks to make its presence on the continent more pronounced even as other more powerful actors express and show an appetite for the same object.[7] However, the growing ‘heavy-handedness’ of Erdogan in his country that has led to a crackdown on dissent after the 2016 coups attempt raises some questions about the political ramifications of Turkey’s presence in Africa.

India’s African Ambitions

India had gained independence as a British colony and protectorate barely ten years before Ghana, the first to be liberated in sub-Sahara Africa, did. The huge and diverse country concentrated on its socialist domestic development for a long time and was occupied with regional politics mostly driven by ethno-religious tensions. Apart from the United Nations, India shared an important forum with African states from the 1960s through its shared leadership of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). The relationship between India and the continent has been based on mutual respect and win-win engagements. The world’s largest democracy also has a very vibrant diaspora population that is economically integrated into many countries across Africa. India has been recognized as a rising power in international affairs in the past two decades. With its popular space program, acquisition of nuclear weapons, robust information technology industry and a huge population set to overtake China, it is a force to reckon with.

The South Asian country has renewed its interest in Africa in many ways that stir the curiosity of political observers. On the diplomatic front, India in 2018 announced the establishment of 18 new missions across the continent.[8] It had earlier sponsored some projects in some countries as part of its soft power projection in Africa. In the 2000s, India sponsored the building of a multi-million-dollar presidential office in Ghana. As of 2018, India accounted for 6.4 per cent of total trade in Africa — which was $ 62.6 billion. This has been a result of years of consistent growth in trade with countries on the continent. However, there was a reduction in the total value of trade to $ 55.9 billion in the 2020-21 year.[9] The charismatic and arguably, controversial Prime Minister Narendra Modi has outlined the guiding principles of India’s engagement with Africa in the areas of trade, agriculture, aid/development, climate change and security/terrorism.[10] India’s influence on the continent and what it means for leadership cannot be overlooked, with its trade on the continent surpassed only by China and the United States, and diversified investment combined with its soft power efforts across borders.

The relationship between India and the continent has been based on mutual respect and win-win engagements.

China’s Growing Influence

From a ‘Pariah’ that had been denied its permanent seat at the United Nations Security Council and held at bay even by its ideological neighbor, China, in the last 40 years, has moved from a provider of support inspired by ‘ideological imperatives’ to African states, to the largest trading partner on the African continent. That was some $200 billion in trade in the year 2019. This, combined with Foreign Direct Investment of $44 billion that same year, makes China’s foothold in Africa potent in the twenty-first century. Chinese investment targets resource-rich states like South Africa, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola, Zambia and Ghana. Other states, including Ethiopia, have also benefitted substantially from infrastructural investment. It is worth noting that China’s economic engagement in Africa is non-discriminatory as it trades with almost every state on the continent. China has also engaged in conspicuous programs and benevolent gestures in advancing its interest through soft power. At various educational centers across the continent Confucian Centers have been established to promote Chinese culture and values to many students. In Ghana, a new center has been established on the main campus of the premier University of Ghana. That has also come with many scholarships for many students studying in mainland China — about 60,000 students on the continent.[11] The country has further had its foreign ministry built by China. China made a diplomatic statement at the continental level by funding the ultramodern Africa Union headquarters in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in 2009. Many of the infrastructural projects on the continent have been under China’s initiative, which is also referred to as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

China has also engaged in conspicuous programs and benevolent gestures in advancing its interest through soft power. At various educational centers across the continent Confucian Centers have been established to promote Chinese culture and values to many students.

Chinese interests in Africa have security and military facets. China has established its first overseas military base in Djibouti, a small state on the Horn of Africa that hosts the US and French military bases. With the sea traffic on adjacent waters joining the Red Sea, the Suez Canal and the Mediterranean Sea, this has been a strategic military decision. It has also signed military pacts with individual states to train their security forces. Military sales have accompanied this on an upward trajectory in value and volume. Its liberal policies behind arms sales have led to huge small arms sales across the continent.[12] These, combined with loans that come with little or no political conditionalities, have made China’s influence on African leaders a concern to liberals. Will China’s overwhelming presence on the continent lead to a conscious or inadvertent adoption of a ‘strongman’ leadership style and or political system hostile to democratic principles?

Competing For and In Africa

The above overview of what may be termed a Euro-Asian interest in Africa points to the fact that emerging global and regional powers and established military powers, like Russia, have developed independent policies to institutionalize their presence on the continent. Such moves are not ends in themselves but means by which their national interests are to be advanced by accessing raw materials, markets for their home industries, diplomatic weight in multilateral fora and security advantage that comes with pacts and military partnerships. The twenty-first century ‘Africa Rush’ is not nouvelle to the continent as European powers had over a century and a decade earlier sat in Berlin and partitioned the continent among themselves. Post-independence, European countries maintain their presence despite their dwindling global power. Until the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Soviet Union and the United States had competed for many of the same reasons emerging powers are doing today, albeit driven by ideological persuasions and territorial buffer creation.

While the Euro-Asian interests on the continent are not surprising to political observers and international watchers, its consequences on African leadership and politics in the medium to long-term have been of concern to some. What makes these concerns intriguing is the fact that these states share some striking commonalities in terms of leadership, domestic politics, regional ambitions, and human rights records. The fear is that political systems and leadership styles could be ‘contagious’ or even more serious; there may be conscious efforts at exporting them to the continent. With incremental democratization of the continent, especially after the Cold War, there are concerns that this could be an antithesis to the democratic gains should it happen. Or is it already happening? What conditions in these emerging powers make their interactions with African states and leaders a matter of concern?

The fear is that political systems and leadership styles could be ‘contagious’ or even more serious; there may be conscious efforts at exporting them to the continent.

The leadership characteristics in these emerging powers have been among the elements they share in common and may justify the wariness of some who remain skeptical about Africa’s exposure. Political engagements between and among states are almost always at the leadership levels, and the effects thereof are felt at the grassroots. Thus, African leaders may find it difficult to immune themselves from the leadership styles of leaders they engage. Of these four countries, India, Turkey and Russia are technically democratic. To the extent that periodic elections are held, political parties operate and participate in domestic politics, and some levels of individual political rights are guaranteed by constitutions, Turkey[13] and, to some lesser extent, Russia[14] are democracies. However, India is the most liberal of these ‘technically democratic’ states. Until recently, Turkey could have been classified with India. China, however, is a self-professed communist state ruled by one party and running a free market economy—a system that has come to be known as socialism with ‘Chinese characteristics.’

The Leaders

All four have leaders who have personalized power or seek to do so within their domestic environments at the individual leadership level. Since the unexpected resignation of Boris Yeltsin in late 1999, Putin has become extremely powerful and has had a tight grip on power in Russia. His allegedly fatal handling of opposition elements and seeming indispensability in the Kremlin has been a worrying situation to liberals worldwide.[15] For the foreseeable future, Putin would be in control.

After Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) instituted a system of presidential tenure that gave individual leaders a maximum of ten years in office to pave the way for a successive generation of leaders to take over. Xi Jinping has been a consequence of this system. However, ever since he assumed office as the General Secretary of the CCP and President of China in 2013, many Chinese experts — albeit not all — have acknowledged that he will defy the convention to extend his rule. In recent times, institutional changes, policy direction, and party hierarchy restructuring have credited these assertions. For the first time since Mao Zedong and, to a far lesser degree, Deng Xiaoping, the CCP has not had a leader as powerful as Xi. His leadership style and assertiveness have been felt beyond the borders of China. The Djibouti military facility earlier mentioned was established under his leadership. The mere fact that he is not leaving the political scene any time soon makes him more potent.

The AKP rode on the back of liberal democratic systems in Turkey to swoop to power. Through strategic alliances with powerful groups and interests like the Gulenists, Erdogan was able to use the government of the Islamist party he had formed to achieve significant economic transformation of the Turkish economy. With this achievement and other successes came what may be called gradual personalization of power and assertiveness in domestic politics.

Erdogan has eventually changed the parliamentary system of government to a presidential one that has given him enormous executive powers and a running room to extend his stay in office at will.[16] The 2016 botched coup furthered his de-facto powers and somewhat rejuvenated his legitimacy as president. The purges that followed the coups were more antagonistic.

Through strategic alliances with powerful groups and interests like the Gulenists, Erdogan was able to use the government of the Islamist party he had formed to achieve significant economic transformation of the Turkish economy.

India happens to be the most liberally democratic of these emerging powers. However, the right-wing rhetoric of charismatic Modi and the consequences on other citizens of India makes him more of a strongman leader than a liberal one. As India runs a federal parliamentary system of government, Modi can run as many times as he would like to, as long as he remains the Hindu-dominated Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP) leader.

The personalization of power by these leaders in their home countries brings into question how their rejuvenated interest in Africa and their resultant association with the ruling class may affect the kind of leadership their counterparts would provide for citizens across the continent. Africa, since independence, has had its problems with leaders overstaying and creating a personality cult around them. That has been the case, from independent leaders like Houphouet-Boigny to those who had assumed power through coups like Gnassingbe Eyadema of Togo.[17] Only a few, like Senghor, voluntarily left power. At the end of the Cold War, the continent saw massive reforms that consequently brought some limitations on some leaders through term limits and pluralism as promulgated in various constitutions they had created and adopted. This did not generally last for long. There seems to be a return to absolutist leadership styles on the continent into the twenty-first century. An engagement by these leaders with external leaders of similar disposition has been considered potentially inimical to democratic governance and smooth transition of power in some African countries. For example, Al- Sisi’s relationship with Putin and how that reinforces the heavy-handed leadership of the former may not be overlooked.[18] Also, the long-running regimes of Yoweri Museveni and Paul Biya and their relations with some of these leaders may be of interest. Thus, leaders from these four emerging powers may encourage or look away from their counterparts in Africa who seek to or are practicing absolutism. Even effective and result-oriented leaders like Paul Kagame of Rwanda have had their relationship with these emerging powers, and their quest to continue to stay in power comes under scrutiny. Generally, Russia and China have had their respective summits with African leaders similar to what western powers have instituted for decades. African leaders attend these summits with much alacrity.

Leaders from these four emerging powers may encourage or look away from their counterparts in Africa who seek to or are practicing absolutism.

Human Rights and Foreign Policies

Another area of concern is the human rights records of the states showing interest in Africa and their relationship with sub-state elements within their borders. The internal intricacies or environment of states may variably be considered by countries seeking to forge close relations with them. When countries have hostile domestic environments, other states consider their relations risky or not worth the effort. In the case of China, Russia, Turkey and to a lesser extent, India, their share economic might as emerging economies has perhaps shrouded such domestic authoritarianism. In Russia, accusations of human rights abuses have been raised against Putin and the ruling party. Incessant and arbitrary incarceration of opposition figures has been mentioned in such accusations to buttress the suppression of the political right of individuals. The occasional allegations against the Russian leadership of using chemical agents to assassinate opponents or dissidents, at home and abroad, are also well registered. The persecution of Jehovah’s Witnesses in Russia is a case in point of the states’ suppression of the individual right to association[19]. China has had its Uighur problem in the Xinjiang province. The suppression of the minority Islamic group is symptomatic of a ‘totalitarian’ tendency China has been accused of since 1949. The Chinese state has also been accused of pervasive human-rights abuses that include the absence of free speech and freedom of association. The argument remains that while communist China can rarely be seen as a free state, the situation has worsened under Xi.

In Turkey, the rights of Kurds in the southeast have frequently been infringed on. Under the cover of their secessionist aspirations, Kurdish groups have been attacked by the superior Turkish forces and faced persecution in mainstream communities. The rhetoric of Erdogan has not helped in reversing the situation. Also, some groups have been targeted and ostracized by the Turkish community after the failed coup of 2016. This is particularly true of followers and adherents of Muhammed Fetullah Gulen, also known as the ‘Gulenists’. Erdogan has sanctioned the detention and persecution and the ostracization of these nationals around the country.[20] He has relentlessly requested that Gulen be extradited to face trial in Turkey, currently residing in the US.

Under the cover of their secessionist aspirations, Kurdish groups have been attacked by the superior Turkish forces and faced persecution in mainstream communities. The rhetoric of Erdogan has not helped in reversing the situation.

Modi’s right-wing rhetoric and indiscriminate exaltation of Hindu culture have turned out to be anathema to the huge Muslim minority of the country that faces discrimination in the sectors of employment, housing and education.[21] Muslims that have been suspected of slaughtering cows in Hindu dominated communities have been occasionally lynched—for committing sacrilege against Hinduism. Despite calls from international actors for the cessation of such intolerant actions, the BPJ has rather capitalized on such rhetoric for political purposes.

Human rights abuses have not been rare in Africa in the twentieth century and currently. From Egypt, where the Muslim Brotherhood is banned from political activities, and Uganda, where Yoweri Museveni is intolerant towards the opposition, and South Africa where labor agitation has been met with gunfire, the continent has a not-so-good record on human rights. Even in some states that have proven democratically robust for the past couple of decades, recent news has been discouraging. For instance, in Benin, the first country to start the late 1980s to early 90s democratization wave, president Patrice Talon has implemented policies that seek to limit political participation and gives him de facto powers to choose who can run for president—a radical departure from over three decades of the liberal democracy.[22] In 2020 a number of Ghanaians were shot dead during the collation of election results at polling stations where they had earlier cast their votes.[23] That had not happened since 1993 when the country started a fourth republic guided by democratic principles. Rwanda has had issues of disappearance and or persecution of opposition figures. The country’s leader has been accused of kidnapping and bringing home political opponents beyond its borders. The ever-growing relationship between the emerging powers from Europe and Asia who have ‘bad’ human rights records with African states, with not-so-good records of their own, raises some pessimistic forecasts regarding human rights on the continent.

Far from coincidence, these emerging powers in recent times have mostly had intransigently aggressive regional and neighborhood foreign policies that threaten regional security. Such policies have led to unilateral decisions and actions that have largely been described as adverse to international peace and security. Therefore, the militarization of regional relations may not be a good example for African nations that have increasingly engaged these states in recent times. Russia’s unilateral seizure of Crimea from Ukraine eventually culminated in its February 2022 invasion of that country. China’s increasing militarization of the South China Sea territorial dispute through artificial island bases may not be a good example to Africa. Turkey’s unilateral invasion of northern Syria and its worsening relations with Greece over Cyprus could also not encourage African states towards good neighborliness. Modi has unilaterally seized Kashmir and made it a de jure province of India, much to the consternation of Pakistan[24]. While this happened after earlier air combat that ultimately embarrassed the former about its capabilities, it took international pundits by surprise.

Russia’s unilateral seizure of Crimea from Ukraine eventually culminated in its February 2022 invasion of that country. China’s increasing militarization of the South China Sea territorial dispute through artificial island bases may not be a good example to Africa.

Obviously, African states dealing with these powers may have little to learn from them in respect of good neighborliness. Admittedly, African states are known to have more internal strife than interstate conflicts. Since independence, many of the conflicts on the continent have been between state and non-state actors who for reasons not exclusive to ideological differences and self-determination had sometimes engaged in macabre clashes.[25] Angola, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan and Mozambique have all fought wars of such nature. Interstate tensions or incursions have not been absent on the continent. There have been times Ethiopia, of its own volition, had entered Somalia with its military to undertake ‘corrective measures’. Chad and Sudan have been blaming each other for harboring rebels and instigating militants against others. The Democratic Republic of Congo has raised issues with the incursion of forces backed by Uganda and Rwanda into its territory. The current dispute over the usage of the Nile River between Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan presents a contemporary example of interstate tensions on the continent.[26] With the sale of weapons by Russia, China, and Turkey to African governments with little or no conditionalities attached, tensions between states may become increasingly militarized in the medium to long term.

In recent times the small oil-rich country of Equatorial Guinea is reported to have had a deal with Russia to supply it with air defense missiles—quite strange for a country with no aerial threat, real or apparent. With a leader that has ruled for over four decades, the use of such weapons is not clear. Angola has also signed deals with Russia to procure fighter jets for its Air Force. The country has been peaceful since the end of its civil war. It, however, has a huge number of its population below the United Nations poverty line. Therefore, oil revenues would be expected to be used for poverty alleviation programs rather than arms procurement. To buy arms worth millions of dollars, Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan have all been courted by arms firms. With tensions over the Nile, these states would have suppliers ready to let in arms without conditions on the use of that to militarize a conflict that could otherwise be solved by dialogue. In future interstate wars that may involve Somalia or Libya, Turkey may be indirectly involved by its established military presence in these states.

To buy arms worth millions of dollars, Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan have all been courted by arms firms. With tensions over the Nile, these states would have suppliers ready to let in arms without conditions on the use of that to militarize a conflict that could otherwise be solved by dialogue.

To the extent that these emerging powers have political issues of personalization of power, human rights abuses, and hostile regional relations, many believe that their new interest in Africa may have local political systems emulating them. Thus, the already fragile politics on the continent may be made worse by the presence of Russia, China, Turkey and, to some extent, India. This would be catalyzed by the funds, diplomatic weight, soft power and arms these states easily bring to the table in the association.

On the other side, none of these powers maintained a colony in Africa, except for the Ottoman empire. The system of colonialism practiced by Europeans in Africa had been exploitative and, in some cases, utterly brutal and inhuman. This makes enthusiasts of the new Euro-Asian interests question the moral right of the West, particularly Europe, to be skeptical about their presence on the continent. They seem to ask, ‘if Europeans have abused the rights of Africans in the past, why should they pontificate on the subject today?’

The absence of political conditionalities with financial assistance given by the new ‘friends’ of Africa has further led to a backlash against western skeptics. The argument remains that western states and financial institutions have so many whimsical conditions attached to financial assistance, some of which seek to undermine the sovereignty of independent states. The conditions have included the limitations on the types of projects loans could finance. Chinese loans and grants have given some African leaders enough room to develop sectors of the economy they see as appropriate and in sync with domestic aspirations. Also, weapons from these states come at relatively low prices than those from the West.

Source: shutterstock.com/Golden Brown

Mutual Benefits?

Mutual respect between China, Turkey, India and Russia, on the one hand, and African states, on the other hand, has been mentioned as among the reasons the former group is increasingly becoming popular in the official government offices across the continent. For decades, India and Egypt have been members of the Non-Aligned Movement, an organization numerically dominated by African states. India’s Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru and Kwame Nkrumah, Josip Tito, Sukarno and Gamal Nasser engineered the movement officially launched in 1961. To this end, African states see these states as peers rather than superior entities intending to impose ideas and systems on them condescendingly. China has also cooperated with African states in South-South cooperation over time. Despite its rapid development in the last three decades, it still considers itself a developing country—an identity it symbolically shares with African states. Moscow commands considerable respect across Africa for its support for some states on the continent during the colonial and anti-apartheid struggle.

For decades, India and Egypt have been members of the Non-Aligned Movement, an organization numerically dominated by African states. India’s Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru and Kwame Nkrumah, Josip Tito, Sukarno and Gamal Nasser engineered the movement officially launched in 1961.

Nevertheless, African leaders, political systems and nationals may endeavor to make the national interest paramount in their engagement with outside powers. While this may theoretically be the case, real issues that make practical the pursuance of the national interest are often ignored.

The continent has states with many of their populations below the poverty line despite enormous resource endowment. Therefore, any ties to external powers must seek to leverage these resources to benefit the suffering masses. Undeniably, some of these external interests have come with educational packages that seek to build a more skilled human resource for the local economies. However, to the extent that the poverty situation on the continent has not improved as fast as expected, leaders must concentrate on the delivery of essentials rather than unimportant military hardware that tend to only add to the prestige of national forces and protection of repressive regimes. Equatorial Guinea’s deal with Russia to acquire surface-to-air missiles is a case in point for a state with massively poor populations despite its rich oil fields.

African states may consider using unified fronts at the continental and sub-regional levels to seek better deals collectively. Continental and sub-regional entities like the Africa Union (AU), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Southern Africa Development Community (SADC), the Inter-Governmental Authority for Development (IGAD), and the East African Community (EAC), among others may build effective common guidelines for external engagements for member states. This would help synchronize the rules of engagement for regional members who have similar social and economic challenges and prioritize issues of importance. With that, future concerns of superfluous arms purchases may be curbed. This should be supported by internal legislation that should be championed by Civil Society Organizations — where possible — to prevent state actors from engaging in whimsical acquisitions that would be detrimental to human development in other sectors of the economy.

Continental and sub-regional entities like the Africa Union, the Economic Community of West African States, Southern Africa Development Community, the Inter-Governmental Authority for Development, and the East African Community, among others may build effective common guidelines for external engagements for member states.

These may help prevent using these relations to turn individual leaders into despots and transform democratic systems into authoritarian ones. Consequently, resources that may accrue from such contacts may be used prudently and transparently to benefit the people. With suitable domestic legislations and regional protocols, leaders cannot capitalize on any external relations to abuse the rights of the people. European countries with adequate national capacities to pursue individual foreign policies have made efforts to synchronize how they collectively relate with outside powers. African states with relatively weak capacities cannot allow parochial interests to block the need to come together and collectively engage the outside world regardless of the powers involved — traditional or emerging.

Fidel Amakye Owusu is an International Relations Analyst with about six years of experience. He has developed an interest in issues concerned with Terrorism, Arms, Governance and Security on the world stage, particularly in the West African sub-region. He has written on these subjects as a columnist for several online news outlets in Ghana. Some of his pieces include, Why Nations Pay Lip Service to Disarmament I&II, Ghana Stands Tall in the Fight Against Terrorism, We Risk Having Nuclear Proxies in South Asia, Drone Revolution in Africa… among others. He has also written peer-reviews papers, including Understanding Terrorism in West Africaand A Message in Afghanistan For Africa. He has five years of working experience with the government of Ghana and has hosted an International Affairs program on state TV. He holds a bachelor’s in Political Science with History and a Master’s in International Relations. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone.

[1] “Mali accuses France of abandonment, approaches ‘private Russian companies,” France 24, News, https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20210926-mali-accuses-france-of-abandonment-approaches-private-russian-companies.

[2] Keir Giles, ”Russian Interests in Sub-Sharan Africa,” Strategic Studies Institute, 2013, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/167578/pub1169.pdf.

[3] ”Russian arms exports to Africa: Moscow’s long-term strategy,” DW, https://www.dw.com/en/russian-arms-exports-to-africa-moscows-long-term-strategy/a-53596471.

[4] Idem.

[5] Charlie Mitchell, ”Turkey builds embassies across Africa as Erdogan boosts influence,” African Business, https://african.business/2021/03/trade-investment/turkey-builds-embassies-across-africa-as-erdogan-boosts-influence/?fbclid=IwAR0ISqBVQR8aaD7YOa0YH-deBFyof_WAZqcgJYbK40ycjt0y_7L17EmOCtY.

[6] ”President Erdoğan visits Ghana National Mosque,” Daily Sabah, https://www.dailysabah.com/diplomacy/2016/03/02/president-erdogan-visits-ghana-national-mosque.

[7] Karen Kaya and Jason Warner, ”Turkey and Africa: A Rising Military Partnership?,” https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/jasonwarner/files/kaya_and_warner_2013_turkey-africa.pdf.

[8] Christian Kurzydlowski, ”What Can India Offer Africa?,” The Diplomat, June 27, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/06/what-can-india-offer-africa/?fbclid=IwAR3N95noga6gHHdeaYnxd7NQGZLM4_J20tYFLV2JGAJwmeg_CMwpvHHaF9s,

[9] Chandarjit Banerjee, ”A makeover for the India-Africa economic partnership,” The New Indian Express, August 17, 2021, https://www.newindianexpress.com/opinions/columns/2021/aug/17/a-makeover-for-the-india-africa-economic-partnership-2345542.html.

[10] Idem.

[11] Paul Nantulya, ”China Promotes Its Party-Army Model in Africa,” Africa Centre for Strategic Studies, July 28, 2020,https://africacenter.org/spotlight/china-promotes-its-party-army-model-in-africa/?fbclid=IwAR1P4m3kAC7Of0ru0CLwdKJ_VMWtd8VR91J9PUXZoBO2yq-20Ghn47VgTRI.

[12] Nyshka Chandran, ”China says it will increase its military presence in Africa,” CNBC, June 27, 2018, https://www.cnbc.com/2018/06/27/china-increases-defence-ties-with-africa.html.

[13] “Edogan onslaughts Rights and Democracy,” HRW News, March 24, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/03/24/turkey-erdogans-onslaught-rights-and-democracy.

[14] Idem.

[15] Sabine Fischer, ”Repression and Autocracy as Russia Heads into State Duma Elections,” SWP Comment, https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/comments/2021C40_Russia_Duma_Elections.pdf.

[16] Hamdi Firat Buyuk, ”BIRN Fact-check: Can Turkey’s Erdogan Run for President Again?,” BalkanInsight, September 09, 2021, https://balkaninsight.com/2020/09/21/birn-fact-check-can-turkeys-erdogan-run-for-president-again/

[17] George Klay Kieh Jr “The “Hegemonic Presidency” in African Politics,” University of West Georgia, ISBN: 978-3-319-49772-3. f

[18] Bassim Elmaghraby, “The Egyptian Foreign Policy Orientations and Its Relations with Russia after June 30th Revolution,” Suez Canal University (Egypt), DOI: https://doi.org/10.22718/kga.2019.3.1.183, https://www.koreascience.or.kr/article/JAKO201913747256182.pdf.

[19] Lena Masri, “Russia’s Jehovah’s Witnesses caught up in “extremist” law,” Reuters, March 31, 2022,https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russias-jehovahs-witnesses-caught-up-extremist-law-2022-03-31/.

[20] Michael Werz and Max Hoffman, “The Process Behind Turkey’s Proposed Extradition of Fethullah Gülen,” Centre For American Progress, September 07, 2016, https://americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/TurkishExtradition-brief.pdf.

[21] Linsdey Maizland, “India’s Muslims: An Increasingly Marginalized Population,”August 20, 2020,https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/india-muslims-marginalized-population-bjp-modi.

[22] Mark Duerksen, “The Dismantling of Benin’s Democracy,” Africa Centre for Strategic Studies, April 27, 2021, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/dismantling-benin-democracy/.

[23] “5 people killed in Ghana election violence,” DW News, https://www.dw.com/en/5-people-killed-in-ghana-election-violence/a-55883334.

[24] Gita Howard, “India’s Removal of Kashmir’s Special Protection Status: an Internationally Wrongful Act?,” University of Miami International and Comparative Law Review, Volume 28, Issue 2, https://repository.law.miami.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1367&context=umiclr.

[25] Barry Buzan and Ole Waever“Regions and Powers The Structure of International Security,” 2003, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511491252. f

[26] Mehari Taddele Maru, “The Nile Rivalry and Its Peace and Security Implications: What Can the African Union Do?,” Institute of Peace and Security, Adisa Ababa (2020), Volume 1, Issue 1, https://media.africaportal.org/documents/The_Nile_rivalry_and_its_peace_and_security_implications.pdf.