Abstract: Cognitive Warfare is gaining ground in the strategic and operational debate. Accordingly, there are various calls for the introduction of a cognitive domain. The partitioning of warfare into operational domains within the framework of Multi-Domain Operations (MDO) effectively reduces the complexity of military decision models as long as the majority of dependencies occur within the individual domains and the interactions between the domains are limited. Using general model theory, we attempt to show that this is not the case when a cognitive domain is added to MDO. Cognitive Warfare is so strongly intertwined with other domains that it does not represent an independent partial model and, therefore, cannot be contained as an independent domain but must be considered within the generally accepted domains.

Problem statement: Is there a need for a cognitive domain in Multi-Domain Operations (MDO)?

So what?: Instead, researchers and practitioners should work together to examine whether other concepts—such as a distinction between domains and dimensions or an extension to include complementary domains—help address the cognitive aspects of warfare in the planning and conduct of operations.

Source: shutterstock.com/Kheng Guan Toh

War As the Father of All?

Clausewitz’s[1] dictum that war is a “true chameleon” remains undisputedly true in the 21st century. Thus, observers, politicians, strategists, and military planners are equally challenged to find ways to conceptualise war and warfare.[2], [3], [4]

Since ancient times, when Heraclitus described war as “the father of all and king of all”,[5] the military has often been the driver of innovation. In recent decades, however, technological leadership has been reversed in many areas. An example of this change in leadership is the concept of “information warfare”, which originates in the civilian description of the current era as the information age; now, the civilian world is in the lead and “war must follow”.[6] Information Warfare can be used by operational planners, strategic decision-makers, and political observers to plan, decide and understand military conflicts.[7] This is vividly illustrated by the example of Ukrainian President Zelenskyy, whose undisputed superiority in the information space has created favourable conditions for kinetic warfare following the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022.[8]

Just as the concept of information operations emerged from the civilian developments of the information age, an analogous transfer is now underway. Cognitive science — an interdisciplinary attempt to understand human thinking[9] — is now making its way into the military world, which is discussed as Cognitive Warfare. Cognitive Warfare as a strategic concept is discussed in detail elsewhere,[10] and attempts have been made to distinguish it from information warfare.[11], [12], [13] There is also a growing tendency to use Cognitive Warfare to explain geopolitical contexts below the threshold of war (e.g., to describe China’s increasing capabilities and offensive approaches[14]). In addition, Cognitive Warfare is entering the conceptual discussion within armed forces, mostly at the operational, but also at the tactical level.[15] Consequently, some authors suggest adding a cognitive domain to the existing physical (e.g., land) and man-made (e.g., cyber) operational domains. Two NATO members, Spain and Poland, have already recognised a cognitive domain.[16], [17]

Cognitive Warfare is entering the conceptual discussion within armed forces, mostly at the operational, but also at the tactical level.

However, military planners should not be tempted by the undeniably increasing complexity of modern warfare[18] to make planning more complex at the same time. As a starting point for discussing the appropriateness of a cognitive domain, the concept of Multi-Domain Operations (MDO;[19]) suggests itself. Stachowiak’s General Model Theory[20] allows us to disentangle this initial situation. Understanding MDO as a model of warfare provides clarity in several respects. First, it becomes clear that the MDO concept serves as an operational model for planners and commanders at the operational level. In addition, MDO can serve as a theoretical model[21] to gain insight into facts in a logically concise form, such as answering whether the cognitive domain has a justification in the model of MDO.

The discussion on the cognitive domain has a significant background. In Europe, the Spanish Armed Forces have established a cognitive domain,[22] as have the Polish,[23] and NATO is debating the need for such a step.[24], [25]

Multi-Domain-Operations

The MDO concept has been used in military doctrine for several years.[26] The term has spread in a generic sense from the U.S. Army through NATO to most Western militaries,[27] including NATO partners such as Switzerland.[28] However, some countries differ in delineating the concept of “operational domain” and which entities they consider as such. This chapter starts with the relevant NATO definitions. It adds three divergent positions to show that current definitions are, at least in part, politically determined.

In January 2023, NATO has defined MDO as“The orchestration of military activities across all operational domains and environments, synchronised with non-military activities to enable the Alliance to create converging effects at the speed of relevance.”[29] This refers to the “operational domain”, defined by NATO in July 2022 as “a specified sphere of capabilities and activities that can be applied within an engagement space.”[30]

In turn, NATO defines “engagement space” as“the part of the operating environment where actions and activities are planned and conducted”,[31] and that the operating environment is “a composite of the conditions, circumstances and influences that affect the employment of capabilities and bear on the decisions of the commander.”[32]

In summary, the purpose of the operational domain concept is to support the planning and conduct of operations. The NATO Terminology Data Base adds to the definition of “operational domain” that “there are five operational domains: maritime, land, air, space and cyberspace, each conditioned by the characteristics of its operating environment.” However, military scholars and practitioners propose other entities of warfare as operational domains.[33], [34]

Several NATO allies and partners also deviate from the above list of five domains. Without claiming to be exhaustive, we distinguish three forms of enlargement: First, the expansion within existing domains. For example, the UK Ministry of Defence is expanding the “cyber domain” to become the “cyber and electromagnetic domain”.[35] This is likely to happen in other countries as well, even if the name of a domain is not changed.

Second, the inclusion of additional domains: Spain has six domains with the addition of the cognitive domain,[36] and Switzerland has seven domains with the addition of the electromagnetic and the information domains separately.[37]

Spain has six domains with the addition of the cognitive domain, and Switzerland has seven domains with the addition of the electromagnetic and the information domains separately.

Third, the differentiation of the notion of domain: France distinguishes between “milieux” (domains) and “champs” (fields) by adding the information field and the electromagnetic field to the five domains,[38] arguing that these fields are also “confrontation domains” (domaines de confrontations), but unlike the “milieux”, the fields do not have their independent command structures.[39] Not only the superordinate term “domaines de confrontations“, but also the internal use of M2MC (multimileux / multichamps) when referring to MDO implies that both “milieux” and “champs” correspond to the English “domain” in the French understanding.

Italy and the U.S. Army provide two other examples of domain differentiation. Italy proposes, in addition to the five NATO domains, “physical”, “virtual”, and “cognitive” dimensions, as well as “information” and “electromagnetic” environments, placing all these concepts side by side;[40] the U.S. Army recognises, in addition to the five domains, “physical”, “information” and “human” dimensions, and places them orthogonally to the domains.[41]

In summary, while MDO has a common origin, there are culturally and organisationally different interpretations within NATO, its members and its partners. Historically, the concept of MDO has been derived from Air-Land Battle[42] and later from joint warfare doctrine.[43] MDO and operational domains have thus emerged from practice. Their definitions are a political consensus since approval requires the agreement of all NATO members. Consequently, the theoretical basis is insufficient to decide which entities can be considered domains.

As a political consensus, the NATO standard represents the lowest common denominator of all member states. Conceptually, such an agreement is a shared mental model,[44] but military practitioners know that politics does not always — to put it mildly — produce the ideal model. This applies both to NATO and to individual members.

So far, the outline is purely descriptive; what we see is what is politically opportune. Nevertheless, to answer whether an additional domain — in our case, the cognitive domain — is justified as an extension, we need a prescriptive approach. Instead of analysing the current understanding of MDO, we need to move to a more abstract level to understand MDO as a mental model. This recognises that MDO “is” not warfare but rather our way of thinking about warfare.

Existing elements and possible extensions of the MDO model are justified only insofar as they serve the planning and conduct of military operations. In complex situations, every unnecessary element leads to a more limited understanding. This can be fatal, especially in warfare situations. Clarity in planning and conduct requires clarity in models.

General Model Theory

People construct models to “clarify, simplify, concretise” when the original is “confusing, entangled”.[45] We can use models for demonstrations, experiments, hypothesis testing and, “in the form of operational models, as decision-making and planning aids.”[46] According to Stachowiak, three main features make up any model: the mapping, the reduction, and the pragmatic feature.[47] We explain them in detail below.

The first is the mapping feature. Models are always models of something, namely mappings or representations of natural or artificial originals, which may themselves be models.[48] The second is the reduction feature. In general, models do not include all attributes of the mapped original. Rather, the model creator restricts the model attributes to those of the original that seem relevant and may add helpful attributes.[49] The third is the pragmatic feature. Models and their originals[50] do not have a bijective relationship. Rather, they fulfil their substitutive function a) for certain subjects, b) within certain time intervals and c) restricted to certain mental or actual operations.[51]

For the following discussion, we need three more terms: First, “attributes” in the sense of the reduction feature. Second, “classes”, that is structured repertoires of possible attributes.[52] Third, “systems”, that is, classes in which each element has (at least) one correlation with every other element of the same class so that the “totality of the class elements forms a ‘uniformly ordered whole’ with respect to this relation”.[53]

Applying general model theory to a given model means explicating the three main features of that model: First, what original does this model map? Second, what attributes, classes, or even systems characterise this model? Third, to whom, when and for what purpose does this model apply? Answering these questions provides a deeper insight into the model and allows hypotheses to be tested.

Application of Stachowiak’s Features to Cognitive Domain in MDO

We now apply General Model Theory to MDO. In doing so, we show that the cognitive domain is not an appropriate extension of MDO. Clarifying the main features of this model provides an analytical or prescriptive approach that goes beyond historical or descriptive views (e.g., [54]).

Undoubtedly, warfare is confusing and entangled, to use Stachowiak’s phrase. Maps covered with tactical symbols, wargames or field exercises are examples of tangible models that military planners and commanders use to grasp the complexities of warfare. However, “model” also applies to abstract concepts such as MDO. The extension of MDO by the cognitive domain thus becomes a testable hypothesis within this model. To do this, we need to answer the questions raised by the features of the present model.

Warfare is confusing and entangled. The extension of MDO by the cognitive domain thus becomes a testable hypothesis within this model.

Mapping Feature

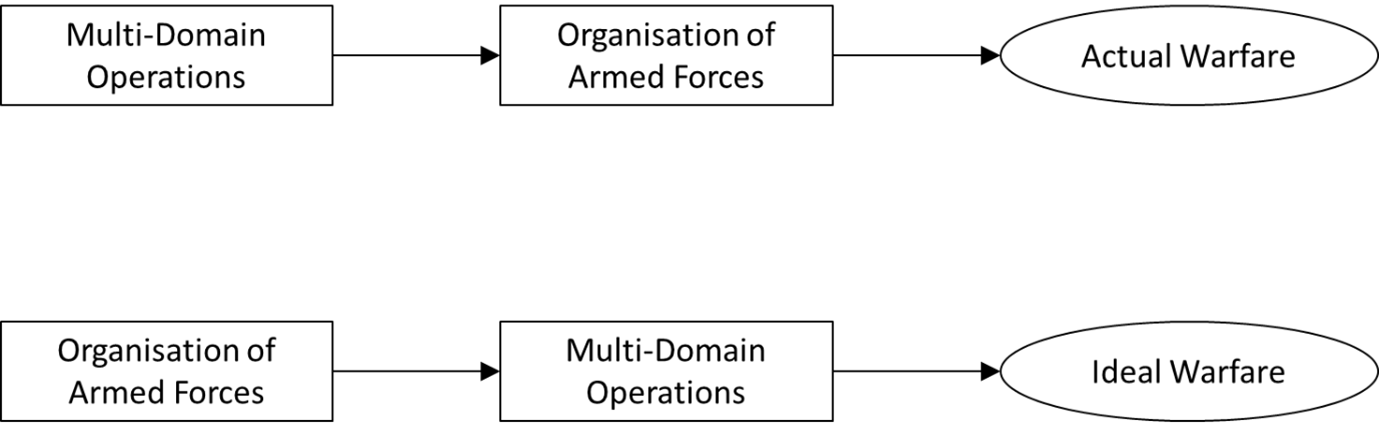

The first question is, what is the MDO concept a model of? The section on MDO distinguished between the descriptive and the prescriptive perspective. The section on general model theory also stated that the original of a model can be a model itself. Furthermore, we argue that the organisation of armed forces is also a model of warfare.[55]

This means that MDO can be understood as either a descriptive or a prescriptive model of warfare. In both cases, the “organisation of armed forces” model plays a different role in what is literally a chain of models.

Ellipses indicate originals; boxes indicate 1st or 2nd order models; arrows indicate “is a model of”. In a descriptive approach (top), the MDO concept is a model of the organisation of armed forces, which are models of actual warfare. In a prescriptive approach (bottom), MDO is an attempt to model ideal warfare, and therefore, armed forces should be organised according to this model.“

In the descriptive sense, the MDO concept is only a conceptual mapping of armed forces, which, in turn, attempts to map actual warfare organisationally. In the analytic sense, the MDO concept is a model for understanding ideal warfare, and armed forces then copy the MDO concept to exploit the pragmatic added value of this model.

The analytic approach can only answer whether a cognitive domain is helpful since a descriptive approach could also map an outdated or otherwise unfavourable military organisation. Disentangling one descriptive example may help to reveal the disadvantage of such an approach: Kreuzer[56] elaborating on the existence of additional domains, called special operations, “multi-domain operation constructs”, and argues that these organisational units are obviously recognisable in armed forces. This is a descriptive approach to what military organisations “do” look, rather than a prescriptive approach to how they “should” look. Kreutzer was not suggesting special operations become an operational domain. However, the example underlines that only a prescriptive approach can answer whether or not a particular construct should be a domain.

Prescriptive models, on the contrary, are representations of ideal warfare. This leads to the essential question about the nature of war: if we see MDO as a mapping of ideal warfare, it depends to a large extent on what one understands by ideal warfare. “Ideal” is not to be understood as the hubris of perfect or optimised warfare; “ideal” refers to our idea of what warfare should be.

How warfare should look is, of course, intricately linked to what war is. Looking at the history of military science, one can broadly divide war concepts into “physical” models and “meta-physical” models. Physical models see warfare primarily as the application of kinetic force. On the contrary, meta-physical models focus, at least in part, on cognitive or other intangible concepts.

Physical models see warfare primarily as the application of kinetic force. Meta-physical models focus, at least in part, on cognitive or other intangible concepts.

Note that there are two different levels of analysis. The descriptive and the prescriptive chains of models are different approaches to the relationship between MDO and warfare. The physical and the meta-physical models differ in the inner structure of warfare. As we have concluded above, the MDO concept is warfare models; they should share the inner structure of warfare, as structural conformity with the original is a characteristic property of models. By showing that only physical models are reasonable models of war, we argue that MDO should thus share the same structure.

Clausewitz is a straightforward example of a physical model of war. Starting with his well-known definition that “War, therefore, is an act of violence to compel our opponent to fulfil our will“,[57] one might think that Clausewitz focuses on “will” and thus follows a metaphysical concept of war. However, his analogy of the two wrestlers reveals that Clausewitzian war is, in fact, a physical concept: “Each strives by physical force to compel the other to submit to his will: his first object is to throw his adversary, and thus to render him incapable of further resistance.”[58]

Although “our will” or “his will” are clearly cognitive terms, the Clausewitzian approach is physical. The will corresponds to a final goal, but it is the physical world (“by physical force”) where the fight occurs; the decision thus occurs in a physical domain. One wrestler has defeated the other when he renders him physically incapable of resistance, regardless of whether his will is broken. Another example of what we call a physical model of war is McManus’ understanding of “a strong likelihood that land is the main arena of decision in war” because of the obvious fact that “human beings are terrestrial creatures.”[59]

In contrast, proposals such as an overarching human domain[60] to “focus on the humanness of warfare”[61] are recent examples of what we call metaphysical models. Historically, Fuller’s model of the mental, moral, and physical spheres may also belong to this category.[62] Transferring meta-physical thinking to the Clausewitzian illustration would imply that the wrestler is not beaten as long as the head has not given up. However, such a position fails, at least in the Clausewitzian analogy.[63] Simply put, there are physical aspects that willpower cannot overcome, such as hypoxia. Suppose — using Clausewitz’s analogy of the wrestlers — we put an opponent in a chokehold. In that case, it will quickly become evident how little willpower affects the situation when they become unconscious.

Obviously, meta-physical models do not apply to Clausewitzian wrestlers. However, deciding whether they are helpful to the operational planner is not a sufficient argument.[64] To show that only physical, but not meta-physical, models prove useful to operational planners and commanders, we take a closer look at a practical example. Because of its cross-domain nature, air war is suitable for this goal.

Air raids are an action in war and should not be confused with breaking the enemy’s will, which is a philosophy in war.[65] History shows that even operationally successful air raids do not automatically produce the intended effect. The capitulation of Serbian President Milosevic in 1999 is a case in point, showing that physical pressure can break morale;[66] by contrast, moral-bombardment achieved as little in World War II[67] as it does today in persuading the Ukrainian population to surrender.[68] Since military planners and commanders are concerned with enabling actions in war, not philosophies, the model they use to think — and plan and decide — must include the entities in which they physically, not those at which their actions are meta-physically directed. This is our first argument against the need for a cognitive domain.

History shows that even operationally successful air raids do not automatically produce the intended effect.

In making this argument, we are not denying the existence of cognitive aspects of warfare. However, cognitive aspects of warfare may act as strategic force multipliers rather than as operational forces in their own right. We can see this in Ukraine, where President Zelenskyy’s — and the wider Ukrainian — performance has been outstanding; however, this willpower would have had considerably less effect if the Ukrainian Armed Forces lacked the physical means to resist.[69]

None of this eliminates the possibility that the cognitive domain may have a role in the context of physical models. However, the cognitive domain has only a secondary role. Thus, like other potential non-physical[70] domains in a physical model, such as cyber, information, or electromagnetic spectrum, the cognitive domain must benefit the military user to justify becoming a domain.

Reduction Feature

Given the origin of ideal warfare, we now look at the attributes to which we reduce this original. By ideal warfare, we mean the warfare we want to conduct. The choice of MDO as a mapping of ideal warfare only makes sense if we consider that ideal warfare implies the simultaneous and synchronised application of force across different domains of warfare. This is essentially the idea of MDO. The model of MDO that we construct thus requires a reduction of the attributes of ideal warfare to those that are useful to the endeavour.

In the MDO model, domains are attributive systems because they form a uniformly ordered whole—the concept of a domain would be useless if the different domains did not have a reasonable set of attributes in common.

In the MDO model, domains are attributive systems because they form a uniformly ordered whole.

This insight does not fundamentally change our understanding of MDO. However, it does allow us to identify crucial attributes that distinguish a domain. Therefore, we need criteria to test whether adding another domain to the attributive system of domains is desirable and valuable.

Allen and Gilbert[71] suggest the following six criteria:

a) Unique capabilities are required to operate in that domain;

b) A domain is not fully encompassed by any other domain;

c) A shared presence of friendly and opposing capabilities is possible in the domain;

d) Control can be exerted over the domain;

e) A domain provides the opportunity for synergy with other domains;

f) A domain provides the opportunity for asymmetric actions across domains.

The six criteria do indeed describe system attributes; more specifically, they belong to three categories. Criteria a) and b) are attributes of spatiality; A) links space to operational forces, and b) refers to the spatial uniqueness of a domain. Criteria c) and d) are attributes of competition; c) allow competition as an articulation of warfare, including the striving for victory. Therefore, d) is required to allow for a winner. Both are very much consistent with the argument that the MDO concept is a model for describing ideal warfare. Finally, e) and f) represent the superposition of spatiality and competitiveness. In this superposition — within the possibility of cross-domain operations — the principle of MDO and their added value for mastering warfare lies. Imagine a domain of warfare with no possibility for synergy with or asymmetric action across domains. Obviously, such a silo would be unhelpful in the context of MDO. Therefore, Allen and Gilbert’s catalogue can be regarded as a stringent set of attributes in terms of model theory.

Although Allen and Gilbert’s[72] list is accurate, it is incomplete. The list describes criteria that compare the formal and material similarity of the model to the original. However, the pragmatic aspect is not considered: MDO is an accurate model of warfare and useful for military planning and conduct.

The partitioning of warfare into multiple domains corresponds to partitioning the decision model of warfare into partial models—a typical procedure for simplifying complex models.[73] Ideally, partial models are formulated so that most of the overall interdependencies are captured within partial models and that any joint effects between the partial models can be easily identified.[74]

We therefore propose an additional criterion for assessing the utility of a domain:

g) A domain reduces the overall complexity of military operations by containing a significant number of internal actions compared to actions across domains.

Using the example of land and air, the interdependencies within each domain are more pronounced than those between domains. It is enough to recognise that the work of planning and conduct is made by distinguishing between the two domains, even though there are cross-domain dependencies. Ultimately, there is a trade-off between how much complexity grows between domains and how much decoupling reduces complexity within domains.

Testing the cognitive domain against the seven criteria, we find three different results. First, criteria a) – d) are met, depending on different interpretations. Second, criteria e) and f) are clearly met. Third, criterion g) is violated. Let us look at these criteria in detail.

For criterion a), the uniqueness of capabilities, the assessment depends on the definition of uniqueness. Since all humans share the same type of cognitive systems, cognitive capabilities are not unique in the strictest sense. Moreover, military actors use the same cognitive capabilities in every other domain. Thus, we can identify emerging capabilities in the sense of future nano-, bio-, information-technologies and cognitive sciences (NBIC).[75] However, it is debatable whether NBIC would not also have an immediate impact in the other domains.

Since all humans share the same type of cognitive systems, cognitive capabilities are not unique in the strictest sense. Moreover, military actors use the same cognitive capabilities in every other domain.

As for criterion b), none of NATO’s five domains fully encompasses the cognitive domain. However, if we allow for an information domain — and there is no reason to exclude it — then cognitive effects that do not occur in kinetic domains may be included in the information domain. So, this criterion folds into the question of whether an information domain or a cognitive domain is the more obvious extension of the MDO model.

For criteria c) and d), dealing with presence and control in the cognitive domain is even more challenging. Conflicting states of mind play out at the individual, not the operational level. We can, of course, turn to cognitive states of collectives, such as mass panic or public opinion. However, then, the question arises as to whether the information domain, in which classical forms of psychological operations take place, is not more useful for planning and conducting operations.

For criteria e) and f), cognition’s relevance and possible impact in armed conflicts are not questioned. Military operations have known cognitive effects such as deception or surprise since the dawn of history. Such effects operate in other domains and in an asymmetric manner, so these two criteria are clearly met.

Criterion g) boils down to the principle of parsimony. The question is not whether cognitive effects play a role in warfare — obviously, they do, as argued above — but whether it is reasonable to confine these aspects of warfare to one domain. Cognitive actions either operate from a different domain (e.g., moral-bombing from the air) or are contained within another domain (e.g., a deception manoeuvre on the ground). Although it is not impossible, it seems difficult to imagine a military operation that occurs exclusively within an assumed cognitive domain. This also reflects the doubts regarding criteria a) to b). If there are indeed self-contained cognitive actions, we can think of them primarily as information operations, which again offers the information domain as an alternative.

MDO is a model of ideal warfare with a clear objective: to enable the planning and conduct of military action. It is, therefore, a decision model. The partitioning into partial models is a common form of simplification. The primary goal is not the clarity of each partial model but that most interdependencies are captured within the partial models. At the same time, only weak compound effects exist between them.[76] It is important to stress that this is not the case for the partial model of a cognitive domain.

MDO is a model of ideal warfare with a clear objective: to enable the planning and conduct of military action. It is, therefore, a decision model.

In summary, we conclude that considering reduction features shows that introducing a cognitive domain unnecessarily increases the complexity of military planning and action. The associated actions can either be handled within the framework of the existing domains or, if so, rather require the introduction of an information domain. The latter, however, needs to be examined elsewhere. We return to this alternative at the end of the concluding section.

Pragmatic Feature

Finally, one may consider Stachowiak’s pragmatic feature. Whether the cognitive is a meaningful domain in the sense of MDO can be answered within the framework of model theory by clarifying a) who uses MDO as a concept, b) for what time frame and c) for what purpose.

First, we answer the question of who. In the military context, this is synonymous with the question of the level of command. Although the concept of MDO has implications at the geopolitical, strategic, operational and tactical levels,[77], [78], [79] it is ultimately an operational concept. At the strategic level, according to COPD, other domains become relevant. Acronyms such as PMESII (Political – Military – Economic – Social – Infrastructure – Information) or DIME (Diplomatic – Information – Military – Economics) indicate that non-military aspects are gaining importance, placing MDO in a broader context. At the tactical level, on the other hand, military action within a given domain is broken down into aspects such as METT-TC (Mission – Enemy – Terrain and Weather – Troops and Support available – Time available – Civil considerations).[80] In between, at the operational level, operational domains are the key concept for military planners and commanders.

Second, we answer the question of when. Operational planning is the attempt to deal with current and future military operations. At the operational level, the current can include actions within days and months; for example, the COPD states that contingency plans should be in their coordinated draft version after 180 days.[81] However, operational considerations must also include a long-term perspective because of the well-known danger of planning for the last war. MDO, as a model, must anticipate future conflicts, as we can see in statements such as that of the U.S. Army[82] with its ten-year perspective (2018-2028). The time frame for MDO is, therefore, “days to years”.

Third, we answer the question of why. This follows directly from the definitions (see our chapter on MDO): It is the planning and conduct of military operations.

In summary, the MDO concept is a decision model that allows military planners and commanders, primarily at the operational level, to plan and conduct warfare within days to years by breaking down the complex warfare model into partial models called operational domains. Each partial model must, therefore, be helpful at the operational level.

However, if we consider a cognitive domain, all its elements are reducible to other domains. This is because the cognitive domain concerns human aspects that affect either the civilian population, and thus the land domain, or the military actors, and thus the corresponding operational domains in which the respective actors operate.

The cognitive domain concerns human aspects that affect either the civilian population, and thus the land domain, or the military actors, and thus the corresponding operational domains in which the respective actors operate.

However, aggregating such actions into a single domain would underscore the importance of cognitive aspects. Indeed, the impact of cognition is undeniable. On land, for example, surprise can completely reverse the kinetic balance of forces; a platoon can destroy a company or battalion in a raid or ambush. Similarly, deception in a naval campaign can permanently change the course of war. However, combining these two cognitive effects into a single domain is impractical for the operational planner. These aspects can and should be better addressed in their respective domains. From a pragmatic perspective, therefore, there is no need for a cognitive domain.

Regarding the mapping feature, we argue that ideal warfare is best understood as a physical rather than a meta-physical concept. Thus, it is the physical domains and not a possible cognitive one — such as the will of the enemy — that operational models such as MDO should seek to capture. Regarding the reduction feature, containing actions in one domain should reduce complexity. From this perspective, the cognitive domain does not make sense either. Nevertheless, if an information domain were established for other reasons, it could include some cognitive activities.

Regarding the pragmatic feature, we can confirm the above results: the MDO is a concept for military planners and commanders primarily at the operational level. Therefore, there is no need for a cognitive domain within an MDO.

No Need For a Distinct Domain

Based on NATO’s definition of an MDO and using General Model Theory, there is no need for a cognitive domain. MDO is a model of ideal warfare, which is physical in nature. Therefore, any cognitive effect should be secondary in such a model. MDO, as a model, is intended to simplify the work of military planners and commanders. However, introducing a cognitive domain is an unnecessary complication of an already demanding task at the operational level.

We do not question the relevance of cognitive warfare. However, from a pragmatic point of view, a cognitive domain does not make sense because the different cognitive effects in warfare are less related to each other than to the particular domain in which they occur.

From a pragmatic point of view, a cognitive domain does not make sense because the different cognitive effects in warfare are less related to each other than to the particular domain in which they occur.

This begs whether and how cognitive aspects of warfare can be mapped in MDO. One possibility is distinguishing between domains and other entities such as “dimensions”, as Italy or the U.S. Army do in their concepts. An alternative is to consider these aspects within the respective domains, at the tactical level or at the higher strategic level, without explicitly representing them in the model at the operational level.

In particular, the question arises as to whether the information domain, as already used by individual countries such as Italy or Switzerland, would not be a more obvious extension. In a common domain, the information domain could accommodate the opposition of different cognitive effects, such as propaganda and counter-propaganda. At the same time, the demarcation of cognitive effects on military personnel, which are clearly assigned to specific domains, would remain clear.

The model-theoretical approach outlined in this paper provides a clear basis for researchers and practitioners to explore and discuss possible extensions, differentiations, or other further developments of the MDO model, focusing on the pragmatic benefits for military planners and commanders.

LTC Patrick Hofstetter, PhD, M.Sc., is Co-Head of Leadership and Communication Studies at the Swiss Military Academy at ETH Zurich. He is an active General Staff Officer in the Swiss Armed Forces and currently commands the Mountain Infantry Battalion 29. His research interests are command, leadership and management in the armed forces. He has published on tactical command and training in the Swiss Armed Force; he co-edited the anthology “Krisenmanagement Schweiz” (2023).

CAPT Flurin Jossen commands the Mountain Infantry Company 48/3. He is also pursuing a bachelor’s degree at the Military Academy at ETH Zurich to become a career officer in the Swiss Armed Forces. His study interests are leadership in extreme situations and the use of technical aids in tactical training. As a future career officer, he will mainly be involved in coaching and teaching reservists of the Swiss Armed Forces.

The views contained in this article are the authors’ alone and do not represent the views of the Swiss Armed Forces or ETH Zurich.

[1] Carl von Clausewitz, Vom Kriege, Ditzingen: Reclam, 1832/1980.

[2] Felix Wassermann, “Chimäre statt Chamäleon: Probleme der begrifflichen Zähmung des hybriden Krieges,” Sicherheit und Frieden (S+F) / Security and Peace, (2016), 104-108.

[3] Michael Evans, “Clausewitz’s Chameleon: Military Theory and the Future of War,” Quadrant, vol. 46, no. 11 (2002), 8-15.

[4] Herfried Münkler, Die neuen Kriege, (Rowohlt Verlag, 2004), 131.

[5] Hippocrates and Heracleitus, Nature of Man. Regimen in Health. Humours. Aphorisms, Regimen 1-3. Dreams. Heracleitus: On the Universe., (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1931).

[6] Martin C. Libicki, What Is Information Warfare?, (Washington, DC.: National Defense University, 1995).

[7] Daniel Ventre, Information Warfare, 2. ed., (London: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2016).

[8] Syahrir Mujib, Agus H. S. Reksoprodjo, Ahmad G. Dohamid and David Yacobus, “The Social Media Dominance: Ukraine’s Key Strategy in the Information War Against the Russian Invasion,” International Journal of Humanities Education and Social Sciences (IJHESS), vol. 2, no. 5 (2023).

[9] Eric R. Kandel, John D. Schwartz, Thomas M. Jessell, Steven A. Siegelbaum and A. James Hudspeth, “Overall Perspective,” in Principles of Neural Science, Fifth Edition, (New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2014).

[10] Oliver Backes and Andrew Swab, “Cognitive Warfare. The Russian Threat to Election Integrity in the Baltic States,” (Cambridge, MA, 2019).

[11] Laurie Fenstermacher, David Uzcha, Katie Larson, Christine Vitiello and Steve Shellman, “New Perspective in Cognitive Warfare,” in Signal Processing, Sensor/Information Fusion, and Target Recognition XXXII, (2023).

[12] Michael Evans, “Clausewitz’s Chameleon: Military Theory and the Future of War,” Quadrant, vol. 46, no. 11 (2002), 8-15.

[13] Herfried Münkler, Die neuen Kriege, (Rowohlt Verlag, 2004), 131.

[14] Tzu-Chieh Hung and Tzu-Wei Hung, “How China’s Cognitive Warfare Works: A Frontline Perspective of Taiwan’s Anti-Disinformation Wars,” Journal of Global Security Studies, vol. 7, no. 4 (2020), 1-18.

[15] Andrew MacDonald and Ryan Ratcliffe, “Cognitive Warfare: Maneuvering in the Human Dimension,” Proceedings, vol. 149, no. 4 (April 2023).

[16] “Defence Technology and Innovation Strategy. ETID – 2020,” State Secretariat of Defence, (Madrid, Spain, 2021).

[17] Zbigniew Modrzejewski, “Information Operations from the Polish Point of View,” Obrana a Strategie, (2018).

[18] Yaneer Bar-Yam, “Complexity of Military Conflict: Multiscale Complex Systems Analysis of Littoral Warfare,” (2003).

[19] COPD V3.0, Supreme HQ Allied Powers Europe, (2021), H-1.

[20] Herbert Stachowiak, Allgemeine Modelltheorie, (Wien: Springer, 1973).

[21] Ibid., 139.

[22] Klaudia Klonowska and Frank Bekkers, “Behavior-Oriented Operations in the Military Context,” Centre for Strategic Studies, (Hague, 2021), 17.

[23] Zbigniew Modrzejewski, “Information Operations from the Polish Point of View,” Obrana a Strategie, (2018).

[24] Bernard Claverie and François du Cluzel, “Cognitive Warfare: The Advent of the Concept of ‘Cognitics’ in the Field of Warfare,” in Cognitive Warfare: The Future of Cognitive Dominance, NATO Collaboration Support Office, (2022), 1-7.

[25] Herbert Stachowiak, Allgemeine Modelltheorie, (Wien: Springer, 1973).

[26] Jose Diaz de Leon, “Understanding Multi-Domain Operations in NATO,” The Three Swords Magazine, no. 37 (2021), 91-94.

[27] Ibid., 93.

[28] OF 17, Schweizer Armee, Regulation 50.020 d (2018).

[29] Military Committee Terminology Board, NATO Glossary of Terms and Definitions (English and French) – AAP-06, 5 ed., vol. STANAG3680, (2023), Record 40728.

[30] Ibid., Record 40695.

[31] Ibid., Record 15752.

[32] Ibid., Record 874.

[33] Patrick D. Allen and Dennis P. Gilbert, “The Information Sphere Domain. Increasing Understanding and Cooperation,” in The Virtual Battlefield: Perspectives on Cyber Warfare, (Ios Press, 2009), 132-142.

[34] Hervé Le Guyader, “Cognitive Domain: A Sixth Domain of Operations,” in Cognitive Warfare: The Future of Cognitive Dominance, (2021).

[35] Joint Concept Note 1/20, (2020).

[36] “Defence Technology and Innovation Strategy. ETID – 2020,” State Secretariat of Defence, (Madrid, Spain, 2021).

[37] OF 17, Schweizer Armee, Regulation 50.020 d (2018).

[38] Julien Sabéné, Richard Gros and Laurent Paquot, “Opérations multi-milieux / multi-champs,” Vortex – Études sur lapuissance aérienne et spatiale, (Juin 2021).

[39] Idem.

[40] Italian Defence General Staff, The Italian Defence Approach to Multi-Domain Operations, Ministry of Defence, (2022).

[41] FM 3-0, Department of the Army, (2022).

[42] Jose Diaz de Leon, “Understanding Multi-Domain Operations in NATO,” The Three Swords Magazine, no. 37 (2021), 91-94.

[43] COPD V3.0, Supreme HQ Allied Powers Europe, (2021).

[44] Arthur T. Denzau and Douglass C. North, “Shared Mental Models: Ideologies and Institutions,” Kyklos, vol. 47 (February 1994), 3-31.

[45] Herbert Stachowiak, Allgemeine Modelltheorie, (Wien: Springer, 1973), 139.

[46] Idem.

[47] Ibid., 131.

[48] Idem.

[49] Ibid., 132.

[50] In Stachowiak’s terminology.

[51] Ibid., 132.

[52] Ibid., 136.

[53] Ibid., 137.

[54] Jonathan W. Bott, What’s After Joint? Multi-Domain Operations as the Next Evolution in Warfare, (Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, 2017).

[55] Kindly asked to check again against the three main features.

[56] Michael P. Kreuzer, “Cyberspace is an Analogy, Not a Domain: Rethinking Domains and Layers of Warfare for the Information Age,” (July 08, 2021), https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2021/7/8/cyberspace-is-an-analogy-not-a-domain-rethinking-domains-and-layers-of-warfare-for-the-information-age.

[57] Carl von Clausewitz, Vom Kriege, (Ditzingen: Reclam, 1832/1980), 4.

[58] Ibid., 4.

[59] John C. McManus, Grunts: Inside the American infantry combat experience, World War II through Iraq, (Nal Caliber, 2010).

[60] Mark Herbert, “The Human Domain. The Army’s Necessary Push Toward Squishiness,” Military Review, (September-October 2014), 81-87.

[61] Ibid., 82.

[62] John F. C. Fuller, The Foundations of the Science of War, (London: Hutchinson &. co, Ltd., 1926), 58.

[63] We thank the reviewer for formulating this crystal-clear argument.

[64] At this point, it becomes evident that the totality of the three features builds the pragmatic character of the model, see [45], 133.

[65] Thanks again to the reviewer for this precision.

[66] Mark Clodfelter, “Aiming to Break Will: America’s World War II Bombing of German Morale and its Ramifications,” Journal of Strategic Studies, vol. 33, no. 3 (2010), 401-435.

[67] Anthony C. Grayling, Among the Dead Cities: Was the Allied Bombing of Civilians in WWII a Necessity Or a Crime?, (Bloomsbury, 2006).

[68] BBC, Mariupol: Key moments in the siege of the city, BBC, (2022).

[69] Again, we thank the reviewer for pointing out this argument.

[70] “Non-physical” is meant colloquially here. The authors recognise, of course, that the electromagnetic spectrum is, in the scientific sense, just as physical as air, land and sea.

[71] Patrick D. Allen and Dennis P. Gilbert Jr., “The Information Sphere Domain. Increasing Understanding and Cooperation,” in The Virtual Battlefield: Perspectives on Cyber Warfare, (Ios Press, 2009), 132-142.

[72] Ibid.

[73] Helmut Laux, Robert M. Gillenkirch and Heike Y. Schenk-Mathes, Entscheidungstheorie, (Wiesbaden: Springer, 2012), 550.

[74] Ibid., 551.

[75] Hervé Le Guyader, “Cognitive Domain: A Sixth Domain of Operations,” in Cognitive Warfare: The Future of Cognitive Dominance, (2021).

[76] Helmut Laux, Robert M. Gillenkirch and Heike Y. Schenk -Mathes, Entscheidungstheorie, (Wiesbaden: Springer, 2012), 551.

[77] Jesse L. Skates, “Multi Domain Operations at Division and Below,” Military Review, 68-75, (2021).

[78] OF 17, Schweizer Armee, Regulation 50.020 d (2018).

[79] Futoshi Takabatake, “NATO’s Approach to Multi-Domain Operations: From the Perspective of the Economics of Alliances,” Defence and Peace Economics, (17 July 2023), 1-14.

[80] FM 3-0, Department of the Army, (2022).

[81] COPD V3.0, Supreme HQ Allied Powers Europe, (2021), H-1.

[82] TP525-3-1, Washington, DC: Departement of the Army, (2018).