Abstract: South Korea, a country – technically – at war with North Korea, faces a population crisis with a decreasing birthrate and growing aging population. Scholarly reports point out that today, the South Korean military works with a manpower level of about 590,000 personnel; however, it is predicted that by 2039, the number of men eligible for conscription will fall from 330,000 per year to about 180,000 per year. This trend is unlikely to be reversed significantly in a short period. Hence, South Korea, a nation surrounded by nuclearized North Korea and China, needs to strengthen its military mechanisms urgently.

Bottom-line-up-front: Through previous research, it is inferred that the long-term solution to the problem of South Korea’s shrinking manpower would be to improve the birthrate of South Korea, but this is not achievable in a short span. Furthermore, implementing this long-term solution could pose other ethical questions regarding the role of women in society. Therefore, the government should focus on the ‘optimum utilization’ of its military manpower by introducing reforms.

Problem statement: How does the population crisis in South Korea affect its military? What could be the possible solutions to make the military stronger?

So what?: South Korea must focus on high-tech oriented armed forces, upgrade its defense mechanisms, use drones, hypersonic, and long-range ballistic missiles, and improve the conditions of working in the military.

Source: shutterstock.com/Stock for you

The 38th Parallel Line and the Birthrate

In 1953, the Korean Armistice Agreement created a border barrier that came to be known as the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). The DMZ is about 4 km wide and 240 km long, and it intersects the 38th parallel line, which divides the Korean peninsula into South Korea (RoK) and North Korea (DPRK). Though the zone is demilitarized, the border beyond the strip is heavily fenced with barbed wire and constantly guarded by soldiers. Described as ‘the scariest place on the Earth’ by Former U.S. President Bill Clinton, the DMZ comprises watchtowers, razor wire, landmines, tank traps, and heavy artillery. Officially, the two countries are still at war, which has required both countries to maintain a standing army.

More than just a formality of “official” war, the standing army is in fact crucial to South Korea, as North Korea poses a constant threat that may lead to the breach of the 38th parallel line. Since the Korean War, South Korea has faced both economic hardship and occasional aggression from North Korea, yet it has prioritized the task of nation-building in response to the military threats it has received. Despite the armistice agreement, North Korea has carried out belligerent acts against South Korea, such as the Rangoon bombing in 1983 and the bombing of Korean Airlines in 1987. Such acts of terror coupled with missile launches have spawned insecurity among South Koreans, resulting in the legal requirement that male citizens undergo compulsory military training for 21-24 months.

Since the Korean War, South Korea has faced both economic hardship and occasional aggression from North Korea, yet it has prioritized the task of nation-building in response to the military threats it has received.

Currently, South Korea has about 590,000 active military personnel. However, the Defense Ministry has predicted that the military manpower could shrink to nearly half its current size within the next two decades. By 2039, the number of men eligible for conscription will fall from the current 330,000 to about 180,000 per year. South Korea’s military is gradually shrinking due to its declining birthrate and increasing aging population. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) ‘s data in 2017, South Korea recorded the lowest birth rate among other OECD countries. South Korea’s total fertility rate (0.84) has been below 1 percent for three consecutive years. In 2020, the number of deaths outpaced the births, marking the natural decline in population for the very first time since such figures have been monitored in the country. Moreover, about “16.5% of the Korean population has aged 65 and older in 2021,” indicating a fast-aging demographic transition in South Korea.[1] According to The Korea Herald, older adults (65 and above) could account for 43.9% of the country’s population by 2050. This could also present a financial burden as the government will have to increase the budget for health and welfare services of senior citizens.

Lower fertility and fast aging pose a challenge to the national security of South Korea, since fewer young people (mostly men) can be enlisted in the military service. Also, the growing demand for social security for the elderly may impact the defense budget required for military reforms. This paper, therefore, is an attempt to comprehend and analyze how declining fertility and increasing aging rate can be challenging to the national security of South Korea, and what can be done to address this issue in the short term.

Conscription in South Korea

South Korea has implemented a conscription system that requires all able-bodied men to fulfill their military duty for about two years. Although both the Koreas signed a truce in 1953, the war never really ended for either of them. In addition, South Korea has relatively powerful neighbors such as China, Japan, and Russia, thus necessitating the conscription system. This system is not without precedent in the country; according to the Military Manpower Administration (MMA), universal conscription was implemented in Korea from ancient times to the Three Kingdoms period (57 BC to AD 668). At that time, most people were farmers, and they used to be summoned at times of emergency or war. During the Goryeo Dynasty, Korea was frequently attacked by foreign invaders. Thus, a dual system of mandatory reserve forces and a professional-regular army was adopted to defend the nation. The MMA mentions that people were enlisted in the military registry regardless of their sex and age. During the Joseon Dynasty, the system changed to “universal conscription of men of age between 16 and 60 years old,” even when there was no war.[2] The conscription system experienced several modernizations until the 1900s. In 1910, when Japan annexed Korea, the Korean conscription system became irrelevant for a brief period until the Korean War.

Presently, Article 39 of the South Korean Constitution reminds all citizens that they have the duty of national defense, thus forming the basis for military conscription. Article 3 of the Military Service Act makes it compulsory for men between 18 and 28 to perform military service, while making it voluntary for women. The conscription system is managed by the Military Manpower Administration that runs under the Ministry of National Defense. Established in 1948, the MMA looks after conscription affairs, including physical examination, recruitment and selection, education and management, force mobilization, research, and management of resources. In 2003, the government revised the Military Service Act to reduce the lengths of active military service by two months, making 24 months for the army, 26 months for the Navy, and 28 months for the Air Force.

Article 3 of the Military Service Act makes it compulsory for men between 18 and 28 to perform military service, while making it voluntary for women.

In South Korea, mandatory military service is not only seen as a stronghold against the looming North Korean threat but also as a symbol of nation-building as the military service encourages “social connection, conformity, hierarchy” and a shared sense of national pride.[3] It also assures South Koreans of deterring the North Korean threat and helps them avert their feelings of insecurity. Therefore, this explains why the shrinking of the military poses a more significant challenge to the national security of South Korea.

Population Crisis in South Korea

South Korea is struggling with decreasing birthrate and increasing aging population, as evidenced by a range of data points on this subject. According to Statistics Korea, for the first ten months of 2021, “deaths outnumbered births by 257,466 versus 224, 216.”[4] Also, the number of births decreased for the 71st consecutive month since December 2015. The number of births fell below the 300,000 mark and stood at 224,216 for the first ten months of 2020”.[5] According to the Interior Ministry, the working-age population (age 15-64) fell to 71% in 2021, down from 73.1% in 2016. In addition, the Seoul Metropolitan Government shows that the “number of marriages in Seoul has fallen by 43% in the last 20 years, down from 78,745 in 2000 to 44,746 in 2020”.[6] Finally, between January to October 2021, South Korea reported a natural population fall of 33,250. Clearly, South Korea’s population is in a state of decline, and has been for some time.

The number of births decreased for the 71st consecutive month since December 2015. The number of births fell below the 300,000 mark and stood at 224,216 for the first ten months of 2020″.

Possible Causes of Low Birth Rate

South Korea is Asia’s fourth-largest economy and is considered a developed country. With a GDP of US$1.8 trillion, South Korea’s economy is expected to continue to benefit from the demand for semiconductors in the market. Nonetheless, South Korea faces the challenge of maintaining its population, which is necessary for sustaining the economy. According to Julian Ryall, the ‘Miracle on the Han River’ created abundant job opportunities and increased the standard of living. It came as a surprise for many Koreans as the country’s economy was erstwhile suffering from the aftermath of the Korean War. Korean families understood the importance of education and began focusing on giving their kids ‘elite education.’ However, the ‘elite education’ comes with a high cost as it puts a huge financial burden on families, meaning that a couple can afford only one child.

Child-rearing is unimaginably expensive in South Korea. A report published by the Ministry of Health and Welfare in 2013 states that “Korean parents spend a total of 308.9 million won ($257,745 USD) on average to raise a child for 22 years,” and these costs can be extended until the child finishes college. By contrast, in China, the average cost of raising a child to the age of 18 is around 485,000 yuan (US$76,629) as of 2019.[7] According to The Korea Herald, the Korean government implemented a state-allowance program in 2013 to make childcare cost-free, but still, “Korean parents with young children spend an average of 2.4 million won (2000 USD) annually” on childcare alone.[8] Additionally, the highly competitive job market does not guarantee a well-paying secure job, and as a result of these financial concerns, people may often choose to give up on marrying and having kids.

Many Koreans indicate that expensive education, overpriced housing, and unattractive jobs drive their decision not to get married. One development which further hints at the overall hesitation to start a family is the fact that there have been several online shows and podcasts in recent years that are aimed at helping people who want to continue living a single life. Shin Haneul, an illustrator, mentioned a podcast titled ‘Behonse’ that roughly translates as ‘world of the unmarried.’ The podcast features several happily unmarried people sharing their experiences.[9] In 2014, the Seoul Metropolitan Government conducted a survey in which only 13.5% of Seoulites felt that marriage is a must.

One development which further hints at the overall hesitation to start a family is the fact that there have been several online shows and podcasts in recent years that are aimed at helping people who want to continue living a single life.

In addition to this change in social mindset, the data provided by Statistics Korea also indicates a fall in the number of marriages registered. For instance, in 1996, about 430,000 marriages were registered, whereas, in 2020, the number fell to 214,000. In April 2018, some job posting sites like Job Korea and Albamon conducted a poll in which 15% of 1,141 adult Korean males and females said that they would never marry.[10] In Korea, marriage is gradually becoming a painstaking activity, which people in their 20s and 30s avoid due to precarious economic conditions. Many young South Koreans are avoiding marriage as they have become too busy with their jobs and thus, they do not want to be involved in numerous intra-familial activities that come after marriage. Furthermore, when people fail to land a safe and well-paid job, they opt for low-paid part-time jobs. This spawns insecurity among Koreans, who eventually give up on marriage, courtship, and babies.

Another crucial reason for the low fertility rate in Korea is gender inequality. South Korea has the 10th largest economy globally, but the country is struggling to achieve higher ranks in gender equality. The Global Gender Gap Index 2021 by World Economic Forum ranks South Korea in the 102nd position. According to OECD 2020 data, South Korea ranked last (31.5%) among the OECD countries with its gender wage gap. This reflects that South Korean women face gender inequality, spurring a crisis in Korean society. The paper Is the Glass Ceiling a Motherhood Ceiling After All? (2019) by Karolina Jennings presents a theoretical background to the relationship between gender inequality and low fertility. According to Jennings, gender equity theory assumes that higher gender inequality causes low fertility as women struggle to have both a career and a family. She also states that education has played an essential role in spreading awareness of patriarchy and sexism.[11] As a result, women have raised their voices against unfair hiring practices and attitudes and forced the government to make significant changes at the workplace. Despite government efforts to enforce laws prohibiting discrimination against women, women still struggle to enter the workforce and advance to leadership positions, as these laws are rarely enforced. Many reports suggested that women employees are paid low wages and are forced to resign after having children. Moreover, women face a ‘double burden’ of child-rearing and office work, disrupting their career paths. Since there are “penalties” for having children, women become part of the Sampo generation and voluntarily give up children, dating, and marriage.

Cause of Increase In the Aging Population

South Korea is also rapidly progressing towards overaging. In his report, Han-hyung Pyo mentions that the disproportionately elderly age distribution of the population in South Korea is caused mainly by the declining fertility rate. Moreover, one cannot deny that South Koreans are living longer as well, further contributing to this imbalanced age distribution. Following the population trends, “South Korea’s average life expectancy rose to 76 years in 2000 from 62.3 years in 1970; and they are expected to live to be 83.1 years old in 2030 and 86.0 in 2050.”[12] Moreover, in 2017, South Korea officially became an ‘aged society’ “with more than 14% of its citizen 65 years old or older.” Statistics Korea reports that the number of people “aged 65 and older stood at 8.53 million” in 2021, and this rate will accelerate to 12.98 million in 2030 and 17.22 million in 2040. Currently, 16.5% of Korea’s population is 65 and above. This will have strong impacts on the health system. Further contributing to the country’s increasing life expectancy are South Korea’s highest-rated universal healthcare system in which treatment for the elderly is paid by the state, and high-quality pension programs.[13] Furthermore, the elderly population of South Korea is relatively healthy due to their living choices. For instance, the aging population belongs to a generation with very low obesity prevalence and low levels of smoking that lead to lower rates of cardiovascular diseases in this age group, which contributes to their growing life-expectancy.[14] Combined with the shrinking birth rate, and South Korea will soon face issues with caring for its elderly population, and related issues with shoring up its national security.

Statistics Korea reports that the number of people “aged 65 and older stood at 8.53 million” in 2021, and this rate will accelerate to 12.98 million in 2030 and 17.22 million in 2040. Currently, 16.5% of Korea’s population is 65 and above.

Impact of Population Crisis on National Security

Lee and Tan (2016) comment that an “increase in life expectancies and plunging birth rates” cause the total population to decline, leading to consequences on the economy and the defense sector of South Korea. A declining birth rate would also mean a decrease in the workforce or labor shortages in the country, detrimental to the economy.[15] Fortunately, it is predicted that South Korea “would continue to outperform its OECD peers” as it has ample headroom in terms of economy. For example, in 2021, South Korea’s economy expanded 4% “at the fastest pace in 11 years” due to an increase in exports and construction activities.[16] Vice Finance Minister Lee Eog-won also expects the economy to continue to grow steadily in 2022 due to post-lockdown recoveries in significant markets and increased Korean exports of chips and petrochemical products.

Although it has been ranked sixth out of 138 countries in terms of military strength in 2021, South Korea’s military is shrinking. Due to the population crunch, the South Korean military is expected to face a personnel deficit from the mid-2020s. Since North Korea has about 1.1 million ground troops, South Korea needs to maintain a large standing force. The military might shrink too much to hold back North Korean forces according to aforementioned projections for the military’s shrinking size by 2039. North Korea’s pugnacious behavior and South Korea being a shrimp among whales bear a bigger threat to the nation. This brings urgency among leaders to rectify the country’s mounting demographic issues to stop the erosion of Korea’s national security.

Since North Korea has about 1.1 million ground troops, South Korea needs to maintain a large standing force. The military might shrink too much to hold back North Korean forces according to aforementioned projections for the military’s shrinking size by 2039.

Decreasing fertility and increasing aging population also put constraints on defense spending. Due to population imbalance, South Korea is expected to increase social welfare and healthcare spending. In South Korea, the government runs senior welfare programs that include pensions, minimum income payments, work provision of seniors, and long-term senior nursing insurance. It has been projected that spending on these elderly programs will increase by 3% every year and could increase to 680 trillion won by 2050.[17] World Bank data shows that from 1995 to 2013, healthcare expenses rose from “3.8% to 7.2% of GDP” in South Korea.[18] The OECD’s data highlight that social welfare costs “accounted for 12.2 % of $1.6 trillion GDP in 2019.” The Ministry of Health and Welfare report also mentions that social welfare would be increasing “to about 20.1% of GDP by the late 2030s and, by 2060, it would account for 28.6% of GDP”.[19] In 2018, social welfare accounted for 11.1 % of the GDP, while the defense budget was roughly 2.9% of South Korea’s $1.6 trillion GDP.[20] If the economic productivity of South Korea becomes weak, expenditure for senior welfare programs may also put constraints on the military expenditure. Moreover, the government has also planned to increase the current retirement age from 60 to 65 to compensate for the decreasing workforce. However, this move may create intergenerational tensions as this move may reduce job opportunities and promotion prospects for the younger generation.

To counter the above-discussed trends and avoid future military weakness, the South Korean government has spent an ‘eye-watering’ amount on its efforts to boost the birth rate. According to Joori Roh, South Korea has spent “the equivalent of a small European economy” to repair this issue of low fertility. From 2006 to 2021, the South Korean Government has spent about KRW 185 trillion ($153.62 billion) – which is about the size of Hungary’s or Nevada’s economy- to pull back the falling birthrate. The government has launched state allowance programs through which expecting couples can claim KRW 500,000 ($420) for prenatal expenses. Parents with children younger than five can also avail of monthly subsidies worth KRW 107,000 ($89.90) per month.[21] Starting from 2022, the government has announced that it will reward childbirth “with 2 million KRW ($1,826) and pay KRW 300,000 each month until the child becomes one,” following the fourth Basic Plan for Low Fertility and Aging Society.[22] If the birthrate deteriorates further and the government spends more, this may impact the overall budget, including defense expenditure. In 2018, the government spent KRW 26.3 trillion ($21.8 billion) on birth policies which “was more than half the defense spending ($38.2 billion) of South Korea.”[23] Already for the 2022 annual defense budget, South Korea is “facing its first budget cut in 15 years,” which would significantly impact the RoK Army’s plan to buy new attack helicopters and to build a light aircraft carrier (CVX). For instance, before the cut, a total of KRW 7.18 billion was allocated to build the aircraft carrier, which was reduced to just KRW 500 million.[24] Thus, if the country were free of such population crisis, the government would have allocated the money spent on pro-natal policies to other public finances or defense modernization.

In 2018, the government spent KRW 26.3 trillion ($21.8 billion) on birth policies which “was more than half the defense spending ($38.2 billion) of South Korea.”

Possible Ways to Tackle this Issue

The permanent solution to stop the shrinking of the military is increasing fertility. However, this long-term solution is time-consuming and would require structural changes in Korean society. Thus, the South Korean government should pursue some viable short-term solutions to increase the optimum utilization of resources in the military.

Graph Source: Carnegie Endowment of International Peace

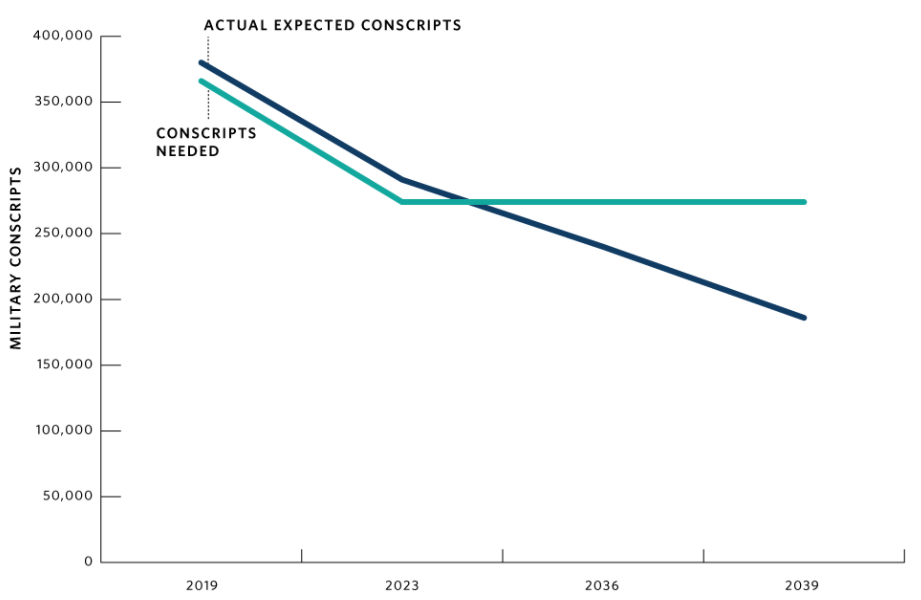

South Korea has predicted a deficit in military conscripts in the future. According to Chung Min Lee (2021), “from the mid-2020s, the South Korean military will face a progressively worsening personnel deficit” if it maintains a baseline force of around 274,000 conscripts.

Reforming Military with Technology

In July 2017, the Moon Jae-in administration announced ‘Defense Reform 2.0’, which President Roh Moo-hyun earlier initiated in 2005 as the ‘Defense Reform 2020.’ The updated defense reform focuses on the “North Korean nuclear and missile threat, better civilian control, waste and fraud related to the defense industry, and human rights for soldiers.”[25] The ‘Defense Reform 2.0’ inculcates a required reduction of force (both conscripts and volunteer forces) from 590,000 to a size of 522,000 troops by 2022. According to the Ministry of Defense, such reduction is necessary “to sustain a conscript force” since the military strength is projected to fall to 161,000 by 2038.[26] Through this reduction, the defense ministry plans to retain essential and must-have positions. While reducing the number of sergeants, lieutenants, the government plans to increase the number of captains, sergeant first classes, and first sergeants. This initiative, coupled with technology, can increase decision-making effectiveness and reduce costs. The Finance Minister of South Korea, Hong Nam-ki, also emphasized that the nation will utilize technologies like weaponized drones, reconnaissance satellites, and aircraft to tackle the issue of the shrinking military.

To mitigate the impact of the population crisis on national security, the South Korean government must promote high-tech-oriented armed forces and pursue new weapons systems. According to Chung Min Lee, a senior fellow at Carnegie Endowment, hypersonic missiles, long-range ballistic missiles, unmanned platforms, powerful submarines like SSBNs, SSNs, SSKs, drones, modernized command, and control systems, and greater use of space assets should be incorporated in the South Korean military. He also emphasizes the fact that the South Korean military must practice a bipartisan defense reform that carries the potential of outlasting the five-year serving terms of governments. After all, the transition of power has previously proven distruptive and wasteful: every five years, a new president comes into power, driven by parochial interests, and brings their version of reforms in the military. Such practice can never mitigate the shrinking military; thus, it is essential to separate politics and national security to focus on making the military stronger.

South Korea is already updating its military with technology as it plans to employ artificial intelligence-powered drones on the battlefield. By 2024, South Korea will be prepared to test a new combat system called The Army Tiger 4.0, short for “Transformative Innovation of Ground forces Enhanced by the 4th industrial Revolution technology,” that includes cutting-edge advances in technology.[27] Moreover, by 2024, ‘Biobots’ – robots based on real creatures – are expected to serve alongside soldiers on the battlefield. South Korea is also working to develop next-generation military robots that will “mimic the movement and capabilities of birds, snakes, marine creatures, and insects.”[28] This initiative is supervised by the Defense Acquisition Programme Administration (DAPA), which understands that South Korea needs to rely on technology to defend itself from external threats. These bio-robots will carry out reconnaissance missions and rescue operations, offloading some burdens from human troops. While autonomous- killer robots are still controversial, South Korea’s use of biobots can be practical as here the robots do not decide when to use deadly force.

South Korea is also working to develop next-generation military robots that will “mimic the movement and capabilities of birds, snakes, marine creatures, and insects.”

Apart from AI-based technology, South Korea is also updating its defense system to enhance deterrence against the North Korean threat. Furthermore, they are cultivating strong military alliances that can alleviate some domestic concerns. The South Korean government aims to reduce its dependency on the USA while maintaining a strong alliance. There are over 28,500 US military troops stationed in South Korea. Moreover, South Korea and America have signed a Special Measures Agreement under which South Korea agreed to pay $1.03 billion to have American troops there in 2021. Although the new Biden administration ended the quarrelsome negotiations begun by the Trump administration for such payments, the South Korean government had to agree to a 13.9% increase ($1 billion annually) in its payment for having American troops in South Korea.

Many South Koreans believe that it is high time that Seoul should achieve ‘true security independence’ from Washington by securing the transfer of wartime operation control authority. Thus, South Korea is heavily ramping up its defense budget to boost its own defense capabilities. It is expected that by 2027, the nation will be spending more than 70 trillion won annually for the defense sector. Under the Moon administration, South Korea has developed a three-pronged defense system: the Kill-chain preemptive strike system, the Korean Air and Missile Defense (KAMD), and the Korea Massive Punishment and Retaliation (KMPR) plan. Minegishi explains that Kill-chain would be used as a preemptive strike against North Korea’s nuclear missile, and the KAMD would be used to trace and shoot down missiles. The KMPR would be a massive retaliation against Pyongyang if it attacks Seoul (2021).[29] Finally, South Korea is planning to build an “aircraft carrier, an ultrasmall satellite, an unmanned air vehicle, a next-generation submarine, and an air defense system” and has also successfully tested a home-made submarine-launched ballistic missile in September 2021. Such developments prepare South Korea to position itself firmly among four surrounding powers and defend itself from a potential North Korean attack.

Making the Military Better

Beyond technological and societal changes to improve the military’s future effectiveness, there are also internal cultural changes needed if the military of South Korea should retain its power in the years to come. Namely, bullying and other toxic cultural norms need to be changed to make the military a more acceptable working environment.

In 2014, a South Korean conscript opened fire on his fellow soldiers, killing five of them while wounding many others. During the investigation, it was revealed that the shooting’s motivations were impacted by bullying. Collective bullying by seniors on their juniors is a common practice in the South Korean military that leads to the deterioration of the mental health of conscripts. During the two years of conscription periods, the conscripts are already isolated from their friends and family and face harsh military-related activities. Bullying coupled with isolation leads to psychological problems among the soldiers. There is also a growing resistance among Korean men who want to skip the military. Some men have even gone as far as to gain weight or lose weight to skip the military on the basis of health problems. Others have changed their citizenship, tattooed their bodies, or claimed that serving in the army is against their religious beliefs. Harsh conditions in the military, such as hazing and sexual harassment, make service unattractive, even leading to suicides among service members.

During the investigation, it was revealed that the shooting’s motivations were impacted by bullying. Collective bullying by seniors on their juniors is a common practice in the South Korean military that leads to the deterioration of the mental health of conscripts.

Still, despite its notorious nature, many Korean men take pride in joining the military. Serving in the army is regarded as sacrosanct and “seen as an integral part of the South Korean male identity,” and if any man skips it, he is often publicly shamed or overlooked by hiring companies.[30] Earlier, if any man refused to serve in the military, he would be imprisoned for about 18 months with a lifetime criminal record. Now, under the new law of 2018, those who refused the mandatory military service on religious or other grounds, would be required to work in a jail or other correctional facility for three years to make up for it.

Reforms are gradually being passed in an attempt to alleviate some of the stress of military service. Under the ‘Defense Reforms 2.0,’ the South Korean government wishes to change public attitudes toward the mandatory military serving system. The government is trying to make the military respect the human rights of the conscripts so that the nation can get physically and psychologically fit soldiers. The Ministry of Defense (MND) first reduced the service terms in 2008 by six months to make conscription more attractive. Nevertheless, in December 2010, the MND froze the reduction time service for the army at 21 months, for the Navy at 23 months, and for the air force at 24 months. Later in 2019, the Defense Ministry allowed conscripted soldiers to use mobile phones inside their barracks for a limited number of hours a day, an activity which had previously been banned. Reports have also stated that communication with families has led to better “mental health and fewer reported incidents of violence” among soldiers.[31] Through the 2022-2026 defense budgeting blueprint, the government has also announced an incremental increase in the monthly wages for South Korean rank-and-file soldiers every year. A sergeant’s monthly salary is also expected to reach 1 million won by 2026 from an estimated KRW 676,100 per month.

Moreover, the Presidential candidate Yoon Suk-yeol from the People Power Party has promised to further raise wages and improve the working conditions of soldiers. In another step towards a less distressing military experience for conscripts, the government launched a task force to review the military’s organizational culture to mitigate bullying and sexual harassment in June 2021. The task force is also working to improve the quality of food served to the soldiers and has called to increase the budget for military meals. Lastly, the Constitutional Court of South Korea has ruled to provide an alternative to those who refuse conscription instead of imprisoning them. Many South Korean men hesitated to join the military but were forced to as they had no other options. Due to poor living conditions and harassment, most men saw mandatory military service as a waste of their youth and thus served the army heartlessly. Nevertheless, the Korean government’s initiative to improve the lives of conscripted soldiers can hopefully improve the military and foster dedication to defending the nation from foreign threats.

Many South Korean men hesitated to join the military but were forced to as they had no other options. Due to poor living conditions and harassment, most men saw mandatory military service as a waste of their youth and thus served the army heartlessly.

Increasing Women and Foreigners’ Participation

As discussed earlier, in South Korea, women can join the military if they ‘want’ to, but they are not required to. Therefore, women’s participation in the military has been limited. According to Yonhap News, in 2019, there were only about 12,602 female soldiers in the army, accounting “for 6.8% of the total forces”. However, Park Yong-jin, a lawmaker from the ruling democratic party, has proposed that all young citizens (both male and female) must undergo mandatory military training for several months. He believes that South Korea would create a strong reserve force through women’s participation while promoting gender equality.[32] There is nothing wrong with making the military mandatory for women if the military makes the environment safe for women. As mentioned above, there have been numerous cases related to sexual harassment in the military.

However, Chung Young-ai of the Gender Equality and Family Ministry thinks that the direction of mandatory military service for women is ‘problematic’. The military should be mandatory only when it can provide a fair and safe environment to the conscripts. She believes that since military service is full of hazing, harassment, and bullying, making it compulsory for women does not promote gender equality but asks women to “experience the same disadvantages that men did” in the military.[33] She further points out that due to unsafe environment of military, women do not prefer to enlist themselves even if they want to. In this way, they lose the military benefits to the men as serving military is compulsory for them. She explains that the extra score system guarantees conscripts (who are mostly men) to gain additional scores at the time of employment and preference during promotions. Thus, it is unfair for women who do not get to serve in the military due to an unsafe environment. In Korean society, instead of participating in military, women are expected to rear sons to serve the nation. Insook Kwon states that in South Korea, mothers of conscript-sons are labeled as self-sacrificing citizens, highlighting that women’s role towards defending the nation is limited to giving birth to sons.[34]

There have been discussions in South Korea regarding overseas Koreans and foreigners joining the military. Currently, naturalized Koreans can join the military if they want to. There is also a rise in the number of naturalized foreigners, with more than 10,000 residing in South Korea currently. The ongoing population crisis may require the government to make it compulsory for foreigners or immigrants to serve in the military if they live in the country for a certain period. However, the brutal conditions of the military are not hidden from anyone. Moreover, if military service becomes compulsory for immigrants, the South Korean government will also have to better integrate multiculturalism and ethnic diversity into society.

There is also a rise in the number of naturalized foreigners, with more than 10,000 residing in South Korea currently. The ongoing population crisis may require the government to make it compulsory for foreigners or immigrants to serve in the military if they live in the country for a certain period.

Conclusion

The South Korean military is expected to face a falling number of eligible young men for conscription each year due to the population crisis. This trend is unlikely to be reversed anytime soon. Therefore, the government must look for quick and feasible remedies as South Korea faces an array of asymmetrical challenges. Undoubtedly, increasing the birthrate is a workable and permanent solution, but it would be time-consuming and require immense efforts by the government. Hence, the RoK military should focus on integrating technology and making military service ‘worthy’ to conscripts by promoting a safe environment and livable conditions.

Torunika Roy, is a Ph.D. scholar of JNU, pursuing research in Korean Studies. She has completed BA in International Studies from Ewha Womans University, Seoul, South Korea and MA in International Relations and Area Studies from JNU, New Delhi. Her research interests are gender, security, soft power, culture and East Asian Studies. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone.

[1] Yonhap, “16.5% Of S. Korea’s Population Aged 65 and Older in 2021: Report,” The Korea Herald, September 29, 2021, http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20210929000712.

[2] “Chronology of the Military Service System, ”Chronology of the Millitary Service System – Overview – Home, accessed February 23, 2022, https://www.mma.go.kr/eng/contents.do?mc=mma0000842.

[3] Jeffrey Robertson, “Debating South Korea’s Mandatory Military Service,” The Interpreter, September 11, 2018, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/debating-south-korea-s-mandatory-military-service.

[4] Yon-se Kim, “Deaths Outnumber Births for 24 Consecutive Months,” The Korea Herald, December 29, 2021. http://m.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20211229000679.

[5] Kim, “Deaths.”

[6] Jullian Ryall, “What’s behind South Korea’s Population Decline?,” DW.COM, December 21, 2021, https://www.dw.com/en/whats-behind-south-koreas-population-decline/a-60210895.

[7] David Stanway, “Bringing up a child costlier in China than in US, Japan- research,” Reuters, February 23, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-child-rearing-costs-far-outstrip-us-japan-research-2022 0223/#:~:text=Beijing%2Dbased%20YuWa%20Population%20Research,per%20capita%20GDP%20that%20year.

[8] Claire Lee, “Koreans Spend 200,000 Won Monthly on Childcare, despite State Allowance: Study,” The Korea Herald, March 5, 2018, http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20180305000207.

[9] Takeshi Kamiya, “Seoul’s Super-Low Fertility Rate Tied to Competitive Society, Finances: The Asahi Shimbun: Breaking News, Japan News and Analysis,” The Asahi Shimbun, May 9, 2021, https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14338131.

[10] Su- jin Park, “One out of Seven Young Koreans Not Interested in Marriage,” One out of seven young Koreans not interested in marriage : National : News : The Hankyoreh, April 15, 2018, https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_national/840587.html.

[11] Karolina Jennings, “Is the Glass Ceiling a Motherhood Ceiling After All?,” LUP Student Papers, (2019), http://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/record/8987101.

[12] Han-hyung Pyo, “South Korea’s Looming Aging Crisis Demographic Change & Challenges of Graying Ahead,” Japan Spotlight, (2009): 26–27, https://www.jef.or.jp/journal/pdf/164th_cover08.pdf.

[13] Yonhap, “16.5%.”

[14] Justin McCurry, “South Korea’s Inequality Paradox: Long Life, Good Health and Poverty,” The Guardian, August 2, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/2017/aug/02/south-koreas-inequality-paradox-long-life-good-health-and-poverty.

[15] Sank-ok Lee and Teck-boon Tan, “South Korea’s Demographic Dilemma: Impact on … – RSIS,” 2016, https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/CO16052.pdf.

[16] Al Jazeera, “South Korea’s GDP Growth Hits 11-Year High as Exports Boom,” Al Jazeera, January 25, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2022/1/25/south-koreas-gdp-growth-hit-11-year-high-in-2021-as-exports-boom.

[17] Jin-seong Cho and Jan R Kim, “Population Aging in Korea: Implications for Fiscal Sustainability,” Seoul Journal of Economics 34, no. 2 (2021): 1-3, https://doi.org/10.22904/sje.2021.34.2.004.

[18] Lee and Tan, “South Korea,” 2.

[19] Chung-min Lee, “South Korea’s Military Needs Bold Reforms to Overcome a Shrinking Population – Demographics and the Future of South Korea,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 29, 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/06/29/south-korea-s-military-needs-bold-reforms-to-overcome-shrinking-population-pub-84822.

[20] Lee and Tan, “South Korea.”

[21] Joori Roh, “Not a Baby Factory: South Korea Tries to Fix Demographic Crisis with More Gender Equality,” Reuters, January 4, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/cnews-us-southkorea-economy-birthrate-an-idCAKCN1OY023-OCATP.

[22] Pulse, “S. Korea to Hand out Cash Rewards for Birth and Additional Childcare Subsidies – Pulse by Maeil Business News Korea,” Pulse, 2020, https://pulsenews.co.kr/view.php?year=2020&no=1286611.

[23] Roh, “Not a Baby.”

[24] Gordon Arthur, “South Korea Faces Serious Defence Budget Squeeze,” Shephard Media, November 25, 2021, https://www.shephardmedia.com/news/defence-notes/south-korea-faces-serious-defence-budget squeeze/#:~:text=South%20Korea’s%20National%20Defense%20Committee,budget%20will%20reach%20only%20KRW54.

[25] HRNK, “Korea Defense Reform 2.0,” 2017: 1–11. Washington DC, USA, https://www.hrnk.org/uploads/files/2017_08_04_koreasdefesereform2_0_inbumchun%20EDITED%20AMO(4).pdf.

[26] Lee and Tan, “South Korea.”

[27] Choi-si Young, “Military Unveils Plans for AI-Powered, Agile Army,” The Korea Herald, September 28, 2021, http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20210928000842.

[28] Ryall, “What’s behind.”

[29] Hiroshi Minegishi, “South Korea Beefs up Military Muscle to Counter Threat from North,” Nikkei Asia, September 14, 2021, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/South-Korea-beefs-up-military-muscle-to-counter-threat-from-North2.

[30] Kelly Kasulis, “South Korea Wants to Draft More Men for Its Shrinking Military – and Punish Those Who Dodge,” The World from PRX, December 9, 2019. https://theworld.org/stories/2019-12-09/south-korea-wants-draft-more-men-its-shrinking-military-and-punish-those-who.

[31] Steven Borowiec, “In the Hands of South Korea’s Military Recruits, a Smartphone Is Their Most Dangerous Weapon,” Rest of World, August 26, 2021, https://restofworld.org/2021/the-most-dangerous-weapon-in-south-koreas-military-is-a-smartphone/.

[32] Timothy W Martin, and Andrew Jeong, “South Korea’s Military Is Shrinking and Some Say Women Must Answer the Call of Duty,” The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, June 3, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/south-koreas-military-is-shrinkingsome-say-women-must-answer-the-call-of-duty-11622727598.

[33] Insook Kwon, “A Feminist Exploration of Military Conscription: The Gendering of the Connections between Nationalism, Militarism and Citizenship in South Korea,” International Feminist Journal of Politics 3, no. 1 (2000): 26–54, https://doi.org/10.1080/713767489.

[34] Young-ha Kim, “South Korea’s Sexist Military,” The New York Times, March 5, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/06/opinion/south-koreas-sexist-military.html.