Abstract: There is a threat of a re-emergence of the idea of Khalistan due to an increase in the propaganda by parts of Sikh diaspora in Western countries, effectively utilizing social media. Further, a sudden spike in social media activity since the opening up of the Kartarpur Corridor in 2019 has raised security concerns. Investigations by security agencies suggest links between Khalistani groups and Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) – further increasing the likelihood of feelings of separatism due to drug trafficking and networking through Sikh pilgrimages. In this context, it is pertinent to understand the re-emergence of Khalistan, wherein traditional propaganda machinery is being used to generate social media acceptance.

Problem Statement: How to tackle the re-emergence of the Khalistan movement backed by traditional propaganda in the garb of social media?

Bottom line-up: The increase in the social media activity of Khalistan sympathizers pose a challenge to India’s national security and sovereignty. By re-emphasizing the events that happened in the 1980s (i.e., Operation Blue Star (OBS), Indira Gandhi’s assassination, subsequent communal massacre, etc.), Khalistani elements in the Sikh diaspora in the Western hemisphere are utilizing propaganda by targeting youth in India and abroad through social media.

So what?: Recognizing the challenge posed by traditional stakeholders and new social media recruits is necessary. The Indian security and intelligence forces need to collaborate with foreign governments to monitor anti-India activities carried out by the Khalistani forces and restrict their funding sources. The Indian government must heighten security efforts to counteract the increase in Khalistani social media activity since the opening up of the Kartarpur Corridor.

Source: shutterstock.com/ChiccoDodiFC

Punjab and the Sikhs

Not long ago, Punjab was soaked in blood, with religious extremism at its peak in the 1980s. The militancy era in Punjab took many lives, including those of former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and Punjab’s Chief Minister Beant Singh. What started as a religious conflict between Nirankaris and radical Sikhs, including Damdami Taksal, became one of the most violent insurgency movements in the history of independent India.[1] The Nirankaris originated from Sikhism as a tiny reformist group under the leadership of Dyal Das in the nineteenth century. The Nirankaris believe in the formless God, who can be reached through a living guru. The relationship between Sikhs and Nirankaris was fraught due to their respective religious beliefs; however, it began to deteriorate further when in 1951, Satguru Avtar Singh proclaimed himself a living guru in the presence of Guru Granth Sahib (Sikhs’ holy book). In 1963, Avtar Singh’s successor, Gurbachan Singh started promoting the mission vigorously by giving provocative speeches and criticizing Sikh gurus. Sikh preachers called Nirankaris Nakli Sikhs (fake Sikhs) and Damdami Taksal were at the forefront of the protest against Nirankaris. On April 13, 1978, the Taksali Sikhs clashed with Nirankaris, leading to the deaths of 13 people. This particular incident on Baisakhi day (a celebration of the Spring harvest) is considered a turning point in the history of Punjab, leading to a series of events that pushed the state into two decades of militancy.[2]

What started as a religious conflict between Nirankaris and radical Sikhs, including Damdami Taksal, became one of the most violent insurgency movements in the history of independent India.

When the militancy finally ended in the late 1990s, Punjab prospered as an agricultural state and became India’s primary supplier of staple food grains. To date, there have been no serious attempts to revive the movement in Punjab as there is an absence of popular support from Sikhs.[3] However, with the advent of social media, there has been an increase in targeted propaganda around the events of the militancy era, particularly those that occurred in 1984. Although the older generation has moved on from the Khalistan dream, some youths of the newer generations of the Sikh diaspora, who have not witnessed the horrors of the militancy, are attracted by the idea of a Sikh nation.[4] It has become necessary to trace the social media activity of Khalistan supporters in the context of the recent spike in communal violence and pro-Khalistan activities.[5], [6]

The Khalistan Movement

The Khalistan movement, which started in the 1940s during British rule, calls for establishing a separate nation for Sikhs. When India became independent and Punjab was partitioned, its leaders demanded a special status for the state. However, the Central Government did not pay attention to these demands, and Sikhs felt betrayed, leading to the idea of a separate nation growing substantially. The introduction of the Green Revolution and capitalist modernization in the 1960s led to the commodification of social life and several fissures in socio-cultural norms. Popular discourse emerged in two phases in response to the aforementioned social crisis. Radical Marxism inspired the first phase, as rural Sikh students attained higher education and came in contact with Marxist ideas. Then, from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, Punjab saw the emergence of the Maoist Naxalite Movement, which appealed to the peasantry background of Punjabi-educated youth. Although the Naxalite movement was suppressed in the mid-1970s, it remained intact through its intellectual and political legacy. What followed the radical Naxalite movement was a religious revivalist movement, filling in the political vacuum left by the former. The movement started when, in response to the increased commercialization of agriculture, an approach of a simple Sikh ethical way of life found an audience among the rural Sikh population. Many individuals and organizations contributed to the Sikh revivalist movement; however, Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale emerged as a charismatic leader after becoming the head of Damdami Taksal on August 25, 1977.

From the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, Punjab saw the emergence of the Maoist Naxalite Movement, which appealed to the peasantry background of Punjabi-educated youth.

Punjabi political parties, such as the Sikh Akali Party, failed to fulfil the regional demands concerning river waters and the transfer of Chandigarh as a capital city to Punjab. The devolution of power gave rise to Bhindranwale’s image among the masses. Bhindranwale advocated using violence as he argued that an armed struggle was more likely to achieve their goal of creating a separate state of Khalistan for Sikhs. Violence between police, government officials, and Sikh extremist organizations started increasing, resulting in former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s decision to suppress the movement by military means. The military mission, OBS, was carried out between June 1 to June 10, 1984, to take control of key gurdwaras, including the Golden Temple in Amritsar, from Bhindranwale’s supporters. Bhindranwale was killed during the operation; however, in recent times, his image remains alive and well.[7] Finding images of Bhindranwale on t-shirts and vehicles while strolling through the lanes of rural Punjab is reasonably easy, signifying an increase in the revitalization of imagery surrounding Bhindranwale. The revival has impacted public memory as Bhindranwale is fondly remembered for his defiance and sacrifice against the Indian state for the Sikh homeland, resembling the Sikh martyrs of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Khalistan Through Social Media

Since the opening of the Kartarpur Corridor between India and Pakistan in November 2019, the social media activity surrounding pro-Khalistan campaigns has increased.[8] Organizations like Sikhs for Justice, Khalistan Liberation Force, and Babbar Khalsa International run misinformation campaigns on social media through Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp.[9] The most recent campaign, which attracted enormous attention, was the Referendum 2020, designed to get the opinion of Sikh diaspora across Europe and North America regarding the establishment of the Republic of Khalistan. The Referendum was set to be held in 2020; however, the COVID-19 pandemic delayed it. On September 19 and November 6, 2022, Khalistan referendums were organized by the pro-Khalistan group Sikhs For Justice in Brampton and Toronto, attracting the participation of over 100,000 and 75,000 Canadian Sikhs, respectively.[10], [11]

Since the opening of the Kartarpur Corridor between India and Pakistan in November 2019, the social media activity surrounding pro-Khalistan campaigns has increased.

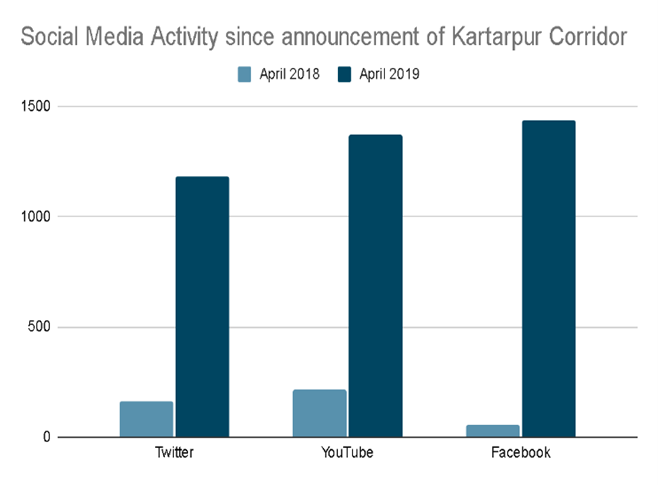

A report by Innefu, a social media monitoring lab working with the Punjab Police, states that the number of propaganda social media posts has increased since the Kartarpur Corridor’s announcement.[12]

Source: Data Compiled by the Author through Innefu Report[13]

Between April 2018 and April 2019, the pro-Khalistan social media content increased in the form of Twitter posts, Youtube videos, and Facebook posts, from 161 to 1181, 218 to 1374, and 56 to 1439, respectively. The sudden increase in the activity on social media reflects that the interest groups are seeking a platform to unite and target the Sikh population. Further, it signifies a trend of identity consciousness among the youth residing in the West and Punjab. As discussed in the following paragraphs, ISI and the terror outfits operating from Pakistan heavily oversee the internet presence of elements spreading Pro-Khalistani content. The posts related to the incidents of the militancy era have generated a renewed fondness for Bhindranwale and his actions against the Indian government of that time.[14]

As part of recent actions taken against the Khalistan propaganda, the Indian government has banned influential Twitter accounts such as 1984tribute, Khalsa Kashmir, and Khalistan Centre.[15] However, the idea of a separate Sikh nation remains popular among parts of the young Sikh diaspora. One such example is the Twitter activity of Aston University’s Khalistan Society, which joined the platform in November 2018 and has 1,055 tweets and posts about Sikh history and Sikh prisoners. It refers to the Indian state of Punjab as ‘Indian-occupied Khalistan.’[16] A similar account idolizing Khalistani leaders, Greater Khalistan, joined the platform around November 2019 and has made 3,464 tweets as of November 2022.[17] The abovementioned accounts were created around when the opening of the Kartarpur Corridor was announced. The operatives of such accounts attempt to propagate the idea of injustices faced by the Sikh community at the hands of the Indian state. On other social media platforms, like Instagram, there has been an increase in engagement with phrases such as Khalistan. There are nearly 92,500 posts with the hashtag #Khalistan Zindabad (Long Live Khalistan). The social media agenda of pro-Khalistan accounts is primarily built upon what happened during OBS and the anti-Sikh riots that followed Indira Gandhi’s assassination. The message from such activity signals toward unjust treatment of Sikhs by the Indian government. Parts of the youth in the Sikh diaspora are more susceptible to such messaging owing to the stories of the valour and courage of Sikhs and their sacrifice to safeguard the Sikh nation from oppressors. The oppressor in this scenario is whichever political party has power at the time. Although social media has been used to control much of the narrative, the traditional propaganda machinery is still alive and well. Over the years, picture galleries of OBS and the 1984 Sikh Riots have found a place in gurdwaras in the USA, Canada, and the UK.[18]

The idea of a separate Sikh nation remains popular among parts of the young Sikh diaspora. One such example is the Twitter activity of Aston University’s Khalistan Society, which joined the platform in November 2018 and has 1,055 tweets and posts about Sikh history and Sikh prisoners.

Additionally, some elements in the diaspora have used the 2020-2021 Indian farmers’ protests as grounds to portray how the Indian state mechanism works against the Sikhs, implying that agriculture and Sikhs are in danger due to the proposed farm bills. In Sikh tradition, labour is regarded as an essential activity, and the farm laws passed by the government were seen as an attack on their livelihood. Further, as mentioned previously, since the militancy, Punjabi Sikhs have had a problematic relationship with anyone running the Central Government. Therefore, the farmers’ protest became a budding ground for some elements in the diaspora to spread the agenda of a Sikh homeland.[19] However, there is no proof of whether the farmers had any direct Khalistani links. During the farmers’ protest, social media activity was heightened and mainly orchestrated by diaspora members. Social media was used to mobilize the masses, raise funds, and create awareness through educational tools.[20]

ISI’s Khalistanis

The present propagation of ideas related to Khalistan is mainly done through social media. The common person is becoming more active on the Internet and adapting to newer technologies. However, such social media activity is generated through traditional networks that still work on the ground in collaboration with Pakistan’s ISI, seeking to create a groundswell for the idea of a Sikh homeland.[21], [22] Leaders of at least a dozen pro-Khalistani outfits continue to live and function in plain sight in Lahore. They are actively involved in organizing funding for operations and supplying transborder shipments of weapons. The prominent example is that of Babbar Khalsa International’s Wadhwa Singh Babbar, who leads the organization from Lahore and is responsible for the assassination of the then Chief Minister of Punjab, Beant Singh. The terrorists operating in Pakistan are suspected of using drones to smuggle weapons across the border into India and playing a key role in raising funds by getting in touch with like-minded individuals and organizations in the West.[23]

Leaders of at least a dozen pro-Khalistani outfits continue to live and function in plain sight in Lahore. They are actively involved in organizing funding for operations and supplying transborder shipments of weapons.

Pakistan’s ISI is using a double strategy of tapping into the Jammu & Kashmir terror network to revive the Khalistan movement in Punjab. By using drugs as a means to radicalize the Punjabi youth, ISI means to destabilize Punjab. At least a dozen cases of drone-based drug consignments have been detected since 2019.[24] In its attempt to recruit youth on social media, ISI formed a new outfit, Lashkar-e-Khalsa, under its K2 (Kashmir-Khalistan) desk.[25] Other than the shipment of weapons and drug supply, ISI is facilitating and promoting the exchange of pro-Khalistan thoughts among pilgrims visiting Pakistan through the Kartarpur Corridor. Although the corridor was exclusively established for pilgrimage purposes, Indian intelligence agencies have reported that there has been a constant presence of ISI agents and Pakistan Intelligence Bureau officials along their side of the corridor.[26]

Implications

The idea of forming a separate state for Sikhs has died down in Punjab; however, it has attracted the attention of a large audience in the diaspora, who recently, in November and September, organized and participated in a referendum to convey their desire regarding the future of Punjab. Further, through social media presence, parts of the diaspora are attempting to spread the narrative around Khalistan by reviving the image of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, OBS, and the consequent anti-Sikh riots. These elements in the diaspora found an opportunity during the farmers’ protest and used it to promote the propaganda of injustice against the Sikh community. The use of social media to propagate misinformation targeted toward a specific section has led to an increase in rural Punjabi Sikh youth being influenced by such propaganda. The Indian government has acted aptly by withholding such social media accounts that may harm or undermine India’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. Such social media activity continuously aims to accumulate ground support in Punjab, which has dwindled since the insurgency ended in 1992. The digital presence of Khalistani elements has revived the legend around Bhindranwale, seen as a Sikh leader who fought against Indian oppression. With an increase in commercialization of imagery around Bhindranwale, the events of 1984, and the recent appearance of Khalistani flags in and around Punjab, it remains to be seen how the propaganda and misinformation campaign unfolds on the ground.

Through social media presence, parts of the diaspora are attempting to spread the narrative around Khalistan by reviving the image of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, OBS, and the consequent anti-Sikh riots.

Using the 1984 anti-Sikh riots as a foundation, parts of the Sikh diaspora have successfully targeted the youth who consider India an illegal occupier. Although substantial ground support is missing, the logistical support from some elements of the diaspora and Pakistan has re-weaponized the once-withering movement. If left unchecked, the misinformation campaign against the Indian security forces and the Indian government will lead to a complete disconnect between the Indian government and the larger Sikh diaspora living in the US, UK, and Canada. Through the calculated use of social media as a tool to mobilize the Sikh diaspora and rural Punjabi youth, Khalistani elements are infiltrating young minds with selective information regarding OBS and Bhindranwale.

India’s Interstate Relations as Part of the Solution

The Sikh lobby in the United Kingdom and the United States has strong roots; therefore, Indian agencies, such as the missions established in those countries, must diplomatically engage with the Sikh diaspora to tackle the misinformation campaign being peddled by Khalistani organizations. Such engagements will facilitate a positive relationship between the Indian state and the Sikh diaspora. Additionally, the agencies should monitor and identify any organizations pumping money into protests and spreading false propaganda. India needs to be wary of ISI and the terrorists hiding in Pakistan more than any other country in the Western hemisphere. Indian security forces need to step up their preparedness to tackle the increase in drones used to deliver weapons and drugs to Punjab. In addition to Western countries, India should not back away from exercising diplomacy with Pakistan and should work to extradite terrorists hiding in Pakistan.

The Sikh lobby in the United Kingdom and the United States has strong roots; therefore, Indian agencies, such as the missions established in those countries, must diplomatically engage with the Sikh diaspora to tackle the misinformation campaign being peddled by Khalistani organizations.

Until Sikhs get closure for the anti-Sikh riots of 1984 by means of court proceedings against the riot accused, the desire for a Sikh homeland will remain strong among the diaspora, who see themselves as a persecuted minority. The violent Khalistani movement has vanished; however, the idea of a separate Sikh nation is yet to disappear.

Shakshi served as a Research Intern at the Indian Council of World Affairs, New Delhi (ICWA). Her area of research includes the Indo-Pacific, India-US relations, Indian diaspora, and India’s national security. Additionally, she has published articles on India’s Balancing Act and the India-US partnership as a primary axis of the Indo-Pacific region. She is working on the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework. She graduated with a BA in Social Science from Panjab University, Chandigarh, in 2020. Currently, she is pursuing her Master’s in International Studies from CHRIST (Deemed to be University), Bangalore.

Shivam Tiwary served as a Management Trainee with MitKat Advisory Services in Mumbai. His area of interest includes India’s domestic politics, geopolitical risk analysis, internal security threats, and international events impacting India’s policies. Additionally, he has published articles on the growth of Indian Unicorns, national waterways, Bihar’s political crisis, and the impact of US involvement in the Ukraine War on the Indo-Pacific Strategy. He graduated with a BA in Journalism from Panjab University, Chandigarh, in 2020. Currently, he is pursuing his Master’s in International Studies from CHRIST (Deemed to be University), Bangalore. The views contained in this article are the authors’ alone.

[1] Ajay Sahni, “Terror in the Wings,” Outlook, February 3, 2022, https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/terror-in-the-wings/234926.

[2] Chitleen K Sethi, “Rivalry between Sikhs & Nirankaris is almost a century old,” The Print, November 20, 2018, https://theprint.in/politics/rivalry-between-sikhs-nirankaris-is-almost-a-century-old/151853/.

[3] Vikas Vasudeva, “Experts wary of sleeper cells in Punjab,” The Hindu, May 15, 2022, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/khalistan-movement-experts-say-concern-over-sleeper-cells-cant-be-ignored/article65413750.ece.

[4] Abhinav Pandya, “Revival of Khalistan Militancy in Punjab,” HW English, March 25, 2019, https://hwnews.in/columnist/abhinav-pandya/sikh-terrorism-2-0/84351/.

[5] “Curfew imposed in Patiala after group clash, one arrested,” The Hindu, April 29, 2022, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/curfew-imposed-in-patiala-after-group-clash/article65367580.ece.

[6] Swati Bhan, “Khalistan flags outside Assembly: Himachal Police to Approach Interpol for Red Corner Notice Against Pannu,” News18, May 9, 2022, https://www.news18.com/news/politics/khalistan-flags-outside-assembly-himachal-police-to-approach-interpol-for-red-corner-notice-against-pannu-5141995.html.

[7] Pritam Singh & Navtej K. Purewal (2013), “The resurgence of Bhindranwale’s image in contemporary Punjab,” Contemporary South Asia, 21:2, 133-147, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09584935.2013.773291.

[8] Regina Mihindukulasuriya, “Pakistan is ‘funding’ pro-Khalistan hysteria online, despite banning on-ground events,” The Print, May 29, 2019, https://theprint.in/world/pakistan-is-funding-pro-khalistan-hysteria-online-despite-banning-on-ground-events/242264/.

[9] JK Verma, “A bid to disturb Peace,” The Pioneer, November 15, 2018, https://www.dailypioneer.com/2018/columnists/a-bid-to-disturb-the-peace.html.

[10] “Khalistan Referendum in Canada: All you need to know,” Mint, September 24, 2022, https://www.livemint.com/news/india/khalistan-referendum-in-canada-all-you-need-to-know-11663648761103.html.

[11] Murtaza Ali Shah, “Over 75,000 Canadian Sikhs vote in Khalistan Referendum despite fierce opposition,” The International News, November 7, 2022, https://www.thenews.com.pk/latest/1007521-over-75000-canadian-sikhs-vote-in-khalistan-referendum-despite-fierce-opposition.

[12] “Open Source Intelligence Report on Khalistan,” Innefu, April 16, 2019, https://www.innefu.com/open-source-intelligence-report-on-khalistan/.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Namrata Biji Ahuja, “Khalistani groups carried out Twitter campaign with ISI help before Ludhiana blast,” The Week, December 25, 2021, https://www.theweek.in/news/india/2021/12/25/khalistani-groups-carried-out-twitter-campaign-with-isi-help-before-ludhiana-blast.html.

[15] Aashish Aryan, “In fresh notice, govt asks Twitter to block 1200 accounts ‘flagged as Khalistan sympathisers or backed by Pakistan,” The Indian Express, February 8, 2021, https://indianexpress.com/article/india/twitter-accounts-block-govt-notice-khalistan-sympathiser-pakistan-7179728/.

[16] Aston University Khalistan Society (@SocietyAston). (n.d.). Tweets and Replies [Twintter Profile]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/SocietyAston?t=RDrpSPmR-LsBDE0N3OqGAQ&s=09.

[17] Greater Khalistan (@GKhalistan), (n.d.) Tweets and Replies [Twitter Profile], Twitter, https://twitter.com/GKhalistan?t=TOQwLMQyE4GoKts5Kj__6A&s=09.

[18] Loveena Tandon, “UK’s largest gurdwara puts up a picture of slain pro-Khalistan leader, stirs controversy,” June 2, 2020, https://www.indiatoday.in/world/story/uk-guru-sri-singh-sabha-gurdwara-jarnail-singh-bhindranwale-slain-khalistan-leader-1684575-2020-06-02.

[19] Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd, “Why the farmer’s protest is led by Sikhs of Punjab,” The Print, December 28, 2020, https://theprint.in/opinion/why-the-farmers-protest-is-led-by-sikhs-of-punjab/574065/.

[20] Tejpaul S. Bainiwal, 2021, “The Pen, the Keyboard, and Resistance: Role of Social Media in the Farmer’s Protest,” Journal of Sikh & Punjab Studies, Vol- 29 (1&2), http://giss.org/jsps_vol_29/13-tajpaul_bainiwal.pdf.

[21] C. Christine Fair, Kerry Ashkenaze, & Scott Batchelder (2021), “Ground Hog Da Din for the Sikh insurgency?,” Small War and Insurgencies, 32:2, 344-373, https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2020.1786920.

[22] Terry Milewski (2020), “Khalistan: A Project of Pakistan,” Macdonald Laurier Institute, https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/mli-files/pdf/20200820_Khalistan_Air_India_Milewski_PAPER_FWeb.pdf.

[23] Praveen Swamy, “How Punjab’s most-wanted yesteryear terrorists are operating openly in Lahore, popping up on FB,” The Print, September 9, 2022, https://theprint.in/india/how-punjabs-most-wanted-yesteryear-terrorists-are-operating-openly-in-lahore-popping-up-on-fb/1121562/.

[24] Anilesh S. Mahajan, “The ghost of Khalistan,” India Today, March 15, 2021, https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/the-big-story/story/20210315-the-ghost-of-khalistan-1775935-2021-03-06.

[25] Raj Shekhar, “ISI has new outfit manned by Khalistani, Kashmiri ultras: Intel,” The Times of India, May 11, 2022, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/isi-has-new-outfit-manned-by-khalistani-kashmiri-ultras-intel/articleshow/91481883.cms.

[26] Mukesh Ranjan, “Intelligence: ISI misusing Kartarpur Corridor,” The Tribune, May 4, 2022, https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/punjab/intelligence-isi-misusing-kartarpur-corridor-391857.