Abstract: The Russian Federation is often portrayed in Western depictions as an overly assertive and unpredictable world power. A look at Russia’s engagement in the Arctic, underpinned by increased military activity, justifies this portrayal even more so. With President Putin’s hold on power secured, a new Arctic strategy in place, and chairmanship of the Arctic Council, Russia is well placed to assert itself as an Arctic power and secure sole supremacy. As sea ice melts, the region’s geopolitical significance solidifies. Due to the vast economic potential, competition among stakeholders has intensified. Climate change has emerged as a key driver of development. The EU is in the process of updating its Arctic strategy. This presents an opportunity to seek practical cooperation about pressing issues such as security, sustainable resource exploitation, trade, as well as the impacts of climate change. This research article addresses the Arctic as an emerging geopolitical hotspot, elaborating on climate change as a major risk. It primarily focuses on Russia’s new Arctic Strategy and that of the EU while providing tangible policy recommendations to build trust within different frameworks.

Bottom-line-up-front: The Arctic has emerged as the stage at which Russia is seeking to regain superpower status. A forward-looking EU Arctic policy offers an opportunity for comprehensive cooperation on enabling environmentally sound resource exploitation. Ultimately, cooperation provides hope for future relations between Russia and the EU.

Problem statement: Given the growing importance of security issues in the Arctic region as well as Russia’s current chairmanship of the Arctic Council, does the EU’s Arctic engagement have the potential to foster cooperation and contain Russian assertiveness, thereby improving multilateral relations and the security situation on the ground? How could a framework for structured security dialogue be established to increase transparency and prevent misunderstandings that can lead to escalation?

So what?: EU-Russia relations are at a low point while the EU attempts to take global responsibility and be a climate policy role model. The EU should use the update of its strategy towards the Russian-dominated Arctic to promote transnational, depoliticized cooperation regarding security, resources, and trade.

Source: Adobe Stock

Introduction

Events such as the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change have revealed grave limitations in relation to world order and geopolitics. They offer opportunities for authoritarian regimes to exert influence and accelerate existing trends, such as economic wars, migration crises, the rise of right-wing populism, and rivalry between superpowers.[1]

Russia’s domestic, military, and foreign policy provide the basis for an in-depth analysis of its strategy towards the Arctic. The Russian Federation is the world’s largest nation and Europe’s[2] immediate neighbor. Over the past 20 years, since President Putin’s rise to power, Russia has become increasingly alienated from the West. Its discontent with the international security order plays a crucial role. Domestically, fluctuations in oil prices and ongoing international sanctions have cast doubt in terms of its economic model. A spiral of growing civil unrest has been met with brutal repression. To the external observer, Russia uses regional conflicts to leverage its sphere of influence and is willing to deploy military forces wherever it deems appropriate.[3] The nation has been undergoing comprehensive reform for well over a decade, with emphasis on increasing versatility and modernizing strategic nuclear capabilities. Russia has expanded its sphere of influence beyond post-Soviet territory, strengthening its military presence in the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Black Sea.[4] Since 2015, it capitalized military activities in the Arctic. In October 2020, a new strategy laid the groundwork for Arctic development and updated Russia’s security policy in the region.

Over the past 20 years, since President Putin’s rise to power, Russia has become increasingly alienated from the West. Its discontent with the international security order plays a crucial role.

Aside from being a coastal state, Russia is a member of the Arctic Council, the leading regional governance forum in the Arctic. Russia has intensified its military activities in the region and invested in the reactivation of infrastructure. Two-thirds of the country’s sea-based nuclear second-strike capability are stationed on the Kola peninsula. Russia claims the heavy military presence is for defensive purposes and that its strategic objectives are based on guaranteeing economic development within the region including freedom of navigation and extraction of natural resources.

Given that Russia is yet to achieve its ambitious economic goals in the Arctic, in part due to a lack of funding and technology, the issue of cooperation is ever more relevant. Western sanctions hinder oil and gas extraction while the Sino-Russian partnershiphas proved incapable of replacing European know-how and overcoming conflicting interests.

The Arctic is where European, transatlantic, and Russian interests intersect. Environmental protection and the use of sea lanes are contentious issues. The EU must endeavor to cooperate with Moscow to avoid spillover effects from bilateral disputes both with individual member states and in other regions, such as Eastern Ukraine. As competition intensifies, the conflicting ambitions of Russia, China, the US, and the EU necessitate a constructive dialogue on military issues. The EU equally should seek effective responses beyond simply advocating for global governance or championing the sustainability agenda of the UN. Although guiding principles have been established, the security dimension needs to be tackled. This would entail a readjustment of European foreign policy so as to engage Russia and narrow the current rift.

Under a security policy lens, the role played by Russia and the EU will be the main focus here. An overview of the political situation in Russia is required to contextualize the research focus, as well as an outline of key Arctic stakeholder policy goals. The EU’s Arctic strategy update coincides with Russia taking over the chairmanship in the Arctic Council. Both parties have entered a decisive phase of engagement in the region, with strategic implications for international relations.

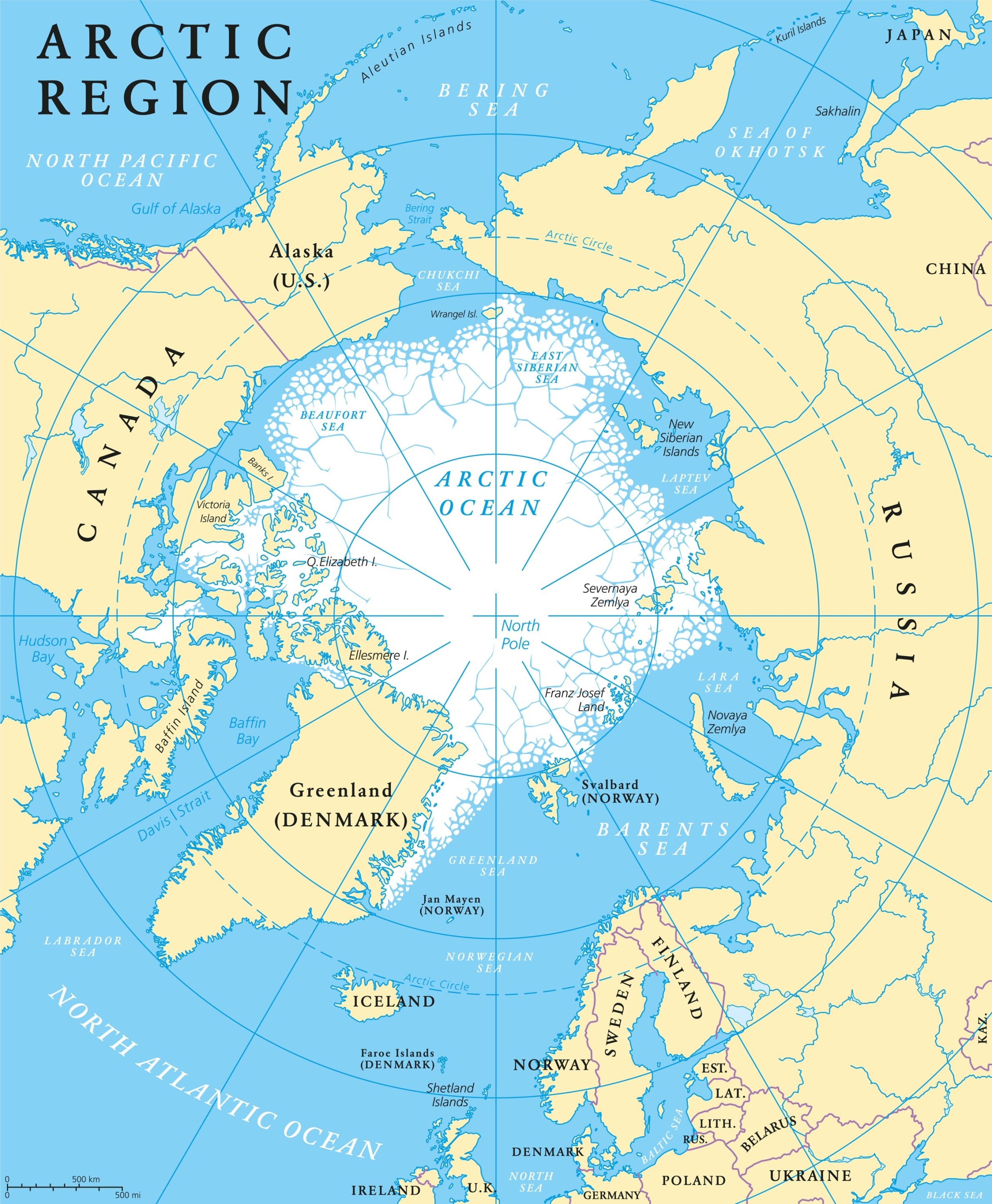

Map of the Arctic region, including countries in the Arctic and members of the Arctic Council: CAN, US, RUS, FIN, SWE, NOR, ISL, and DEN. Source: https://stock.adobe.com/de/images/arctic-region-map-with-countries-capitals-national-borders-rivers-and-lakes-arctic-ocean-with-average-minimum-extent-of-sea-ice-english-labeling-and-scaling/113448254

Facts and Figures: Policy Landscape of the Arctic

The region extends from the North Pole to the boundary of the Arctic Circle[5]. It is mainly a sea surrounded by five states with an Arctic shoreline. These are: Denmark, Canada, the Russian Federation (Siberia), Norway (Svalbard), the US (Alaska), as well as three states with Arctic land: Finland, Iceland, and Sweden. Together, said eight states have joined to form the Arctic Council, which has long played an essential role in international security policy.[6] It is home to four million people, 70 percent of whom live on Russian territory – approximately 10 percent are indigenous.[7]

During the Cold War, the Arctic was one of the most militarized regions in the world. While no violent conflict occurred, continuous tensions between the US and the Soviet Union hindered regional cooperation. This began to change in 1987 when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev initiated a series of measures known as the Murmansk Initiative. The goal was to reduce military activity by creating a nuclear-free zone, restricting naval activities, and promoting cross-border cooperation. Ultimately, interstate relations were depoliticized and the importance of the Arctic shifted from a security policy arena to one of multilateral cooperation free from geopolitical tensions, a phenomenon referred to as “Arctic exceptionalism”.[8]

The prospect of greater access to the region due to rising temperatures multiplies on the Arctic’s prominence, leading to strategic competition between Russia, China, and the US.Moscow continues to rely on cooperation among stakeholders while significantly increasing its military presence. This poses a security dilemma for the US and its allies about whether it should increase military involvement or maintain the fragile status quo. Despite this precarious situation, there is no multilateral body that deals with military security in the region.[9] Given that it is warming faster than the global average,[10]its people, ecosystems, and resources will profoundly be affected. More accessible sea routes and unexploited mineral resources add to the region’s significance.[11] These developments bring the Arctic to a geostrategic focus and have profound security implications that affect international relations, economic activity, and military buildup.[12] Addressing climate change and adapting to new challenges will require enhanced effort from all fronts.

During the Cold War, the Arctic was one of the most militarized regions in the world. While no violent conflict occurred, continuous tensions between the US and the Soviet Union hindered regional cooperation.

The Arctic Council is the most important intergovernmental forum of Arctic governance.[13] It promotes cooperation on regional issues concerned with environmental protection and sustainable development. However, defense and military are not covered.[14] The eight states with sovereignty over Arctic territory are represented.Some non-Arctic states have been granted “observer” status and can contribute to the Council’s work, which is based on consensus and lacks the power to enforce international law.[15] Thus, most policy issues fall within the sphere of domestic law.[16] A two-year rotating chairmanship offers individual Arctic states the opportunity to shape the agenda and pursue political priorities. In May 2021, Russia took over the chairmanship from Iceland.

Russia and the EU: Analysis of Two Strategies Targetting the Arctic

Russia’s new Arctic Development Strategy[17] articulates vital national interests and visions through to 2035. More than 80 percent of Russia’s natural gas and about 17 percent of its oil is generated in the Arctic.[18] However, the decay of infrastructure caused by the thawing of permafrost poses significant challenges. Selected measures to exploit its potential include the improvement of sea rescue capabilities, the modernization of seaports and airports along the Northern Sea Route (NSR), and the construction of nuclear icebreakers. While the new Development Strategy includes a section on international cooperation, it also highlights the growing potential for conflict and demands an increase in military forces.

Despite neither being an Arctic state nor a granted observer status in the Arctic Council, the EU has elaborated its own strategy for the region.[19] Among those are structural funds, transport networks, digital infrastructure, and innovative technologies. Three Arctic states are members of the EU, namely Denmark, Finland, and Sweden. The strategy focuses on climate change, environmental protection, and sustainable development. It considers the inclusion of a security policy dimension and takes a position on Russia’s military buildup. Nevertheless, experts disagree on whether or not it is the right way to go.

Three Arctic states are members of the EU, namely Denmark, Finland, and Sweden. The strategy focuses on climate change, environmental protection, and sustainable development.

Russia’s Strategic Goals and Military Engagement in the Arctic

Russia’s chairmanship of the Arctic Council offers Moscow a chance at advancing its strategic objectives, set out in its 2008 Russian Arctic Policy and developed further in the 2013 Development Strategy of the Arctic Zone.[20] The region generates around 15 percent of the country’s GDP.[21] Nevertheless, climate change and prevailing soil conditions require a fundamentally more costly approach. Russia does not rule out foreign contributions, on the condition that Russian sovereignty is not compromised. At the same time, Moscow shows environmental awareness and signals interest in political stability. As the region’s economic importance grows, Moscow fears the possibility of an attack from American or Chinese warships through the Bering Strait or from the West via bases in Greenland, Iceland, and Norway.[22]

A long tradition of polar exploration evokes nostalgia for Russia’s role as a natural sovereign leader in the Arctic.[23] After the end of the Cold War, Russia and the US reduced their forces in the region. It was not until the 2000s that Moscow rediscovered the region’s geopolitical importance, culminating in a demonstrative planting of the country’s flag on the seabed of the North Pole in 2007.[24] Since then, the Kremlin has published its first comprehensive document on Russian Arctic policy. It sets out the goals and priorities to position Russia as a “leading Arctic power”. Meanwhile, the Kremlin has increased its military presence while highlighting the defensive nature of its actions. Russian narratives portray a peaceful military posture by focusing on military modernization, with a view on ensuring the sovereign rights of Russia’s Arctic.[25]

After the end of the Cold War, Russia and the US reduced their forces in the region. It was not until the 2000s that Moscow rediscovered the region’s geopolitical importance.

The new Arctic Development Strategy, adopted in October 2020, introduces Moscow’s 15-year plan. Building on Russia’s 2008 Arctic Policy Paper, 2013 Arctic Strategy, and 2015 National Security Strategy, its main objectives are to establish Russia as the leading Arctic stakeholder, strengthen combat capabilities, modernize military infrastructure, and exploit the region’s economic potential.[26]

To assert Russia’s sovereignty within the largely maritime Arctic region, the 2020 strategy is centered on the development and security of the NSR as “a globally competitive national transport corridor”.[27] The importance of a developed port, rescue, and digital infrastructure is emphasized. Nonetheless, while transportation volume targets remain uncertain, Russia’s goal is to transport its raw materials rather than develop an open transit route between Europe and Asia.[28]Strategically, Russia envisages exclusive use of a protected route in times of conflict to ensure its second-strike capability.[29] Moreover, a new A2/AD (Anti Access/Area Denial) missile air defense system covers all islands and archipelagos along the NSR, enabling Russia to prepare for rapid escalation in the event of a conflict.[30]

Russia’s Enhanced Military Capabilities in the Arctic

Through expanding its military activities in the Arctic, Russia aims to protect its national interests and critical infrastructure.[31]The NSR ensures access to the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. From a military perspective, the Arctic is both Russia’s backyard and operational area for its Northern Fleet. The establishment of the Murmansk-based Northern Fleet Strategic Command in 2014 was a crucial moment in its Arctic military strategy evolution. The primary purpose was to project power, coordinate all Russian military units, and strengthen the territorial defense of the Kola Peninsula, whereby two-thirds of Russia’s sea-based nuclear second-strike capability is stationed.[32] The Northern Fleet is also equipped with the world’s largest nuclear and non-nuclear icebreaker fleet, air and coastal defense systems, electronic warfare capabilities, and radar systems.Its forces completed a significant number of military exercises in 2020, including military observation flights, the first-ever large-scale airborne exercise in extreme conditions over Franz Josef Land, and the “Ocean Shield” maneuver of the naval forces.[33] The formalization of the Northern Fleet as an independent military district emphasizes Russia’s strength and the vital role the Arctic plays in its military thinking.

The establishment of the Murmansk-based Northern Fleet Strategic Command in 2014 was a crucial moment in its Arctic military strategy evolution.

With the expansion of military capabilities in the Arctic, Russia continues with the reactivation and modernization of structures dismantled after the Soviet era.In late 2019, Russia deployed some 12,000 troops, five nuclear submarines, fifteen warships, 100 aircraft, and the first-ever “combat icebreaker” in the Arctic. Activities included simulated air strikes on radar installations in Norway and Finland, and submarine thoroughfares – the largest of its kind since the end of the Cold War.[34]Russia is also upgrading its northernmost airbase, giving Moscow advanced capabilities to defend its territory and strike the US Thule Air Base. The “Zapad 2017”, a joint Russian-Belarussian military exercise tested defense capabilities against air and missile attacks. “Zapad 2021” will be similar.[35]“Vostok 2018”, the largest military maneuver in the history of the Russian armed forces, which covered large parts of Siberia, the Arctic, and the Pacific Ocean, served to test combat readiness and involved thousands of Chinese forces for the first time. Vostok strategically presented a unified Sino-Russian front against the rest of the Arctic community. “Tsentr 2019” was the first exercise aimed explicitly at demonstrating Russia’s response capabilities along the NSR.[36]

“Vostok 2018”, the largest military maneuver in the history of the Russian armed forces, which coveredlarge parts of Siberia, the Arctic, and the Pacific Ocean, served to test combat readiness and involved thousands of Chinese forces for the first time.

From a geopolitical standpoint, Russia’s aims to defend itself against potential adversaries and bolster its claim to around 1.3 million square kilometers of Arctic territory.[37] The continued deployment of additional naval units and coastal defense systems could convert the entire Arctic into an A2/AD zone. The strengthening of its military has always been framed as exclusively defensive by the Russian government.[38] Regardless, as expansion intensifies, so does Russia’s ability to conduct offensive operations in the event of conflict.[39]

Outlook & Assessment of Russia’s Strategic Objectives in the Arctic

Russia is interested in the Arctic for its natural resources, strategic military use, and a unique opportunity to legitimize Putin’s regime. Russia’s identification with the region stems from its tradition of polar exploration, the Stalinist era of heavy militarization, and close assimilation with Arctic culture. Arctic heritage helps to contextualize Russia’s self-presentation as a principal stakeholder.[40] It has the largest share of territory, resources, and population in the region. Their protection is a domestic political priority that holds a special place in Russian military doctrine. Better said, it sees the Arctic through a sovereign-centric lens, arguing that the region has always been part of its sphere of influence. It has been called the “Arctic hegemon.”[41]

Moscow envisions a dual function for the region. Externally, it maintains the country’s reputation and status as a superpower. Internally, it serves as a strategic resource for socio-economic development. The new 15-year Arctic Strategy is oriented towards economic development: to support Arctic resource exploitation and private investment in energy industry projects. Intriguingly, its policy appears ambivalent with the attempt to unite industrial, economic, and military interests. It focuses on national sovereignty while advocating the need for external funding. Moreover, it contains both confrontational and cooperation-oriented elements, favoring political competition or practical cooperation depending on the issue.[42]

Although Putin has committed to the Paris Climate Agreement,[43] Russia’s economic model is based on fossil fuels.[44] It relies on aging infrastructure to exploit the region’s resources.[45]

Moscow is interested in political stability and calculable international cooperation to tap into the region’s potential. Despite the proximity often portrayed, China does not appear to serve these interests, especially since Russia is unwilling to relinquish its control over resource transportation or allow foreign involvement in critical infrastructure. Instead, Russia is building its fleet of nuclear-powered icebreakers to ensure control over the Arctic with year-round accessibility to cargo ships and plans to make the NSR competitive with the Suez Canal from 2030. Overall, Russia’s objectives seem broad and overambitious based on political rhetoric and inflationary threat perceptions.

Despite the proximity often portrayed, China does not appear to serve these interests, especially since Russia is unwilling to relinquish its control over resource transportation or allow foreign involvement in critical infrastructure.

While emphasizing the economic importance of the Arctic, the strategy seeks continuity and sees the thawing of permafrost primarily as an economic challenge. A major risk is that Russia pays lip service to climate and environmental protection, perpetuating fossil fuel-focused Arctic development. Hence, the success and sustainability of the Arctic will largely depend on Russia’s ability to engage in win-win cooperation with adequate partners who can offer financial resources and technological know-how. Otherwise, their goals are likely to remain mere statements of intent.

Russia’s Arctic policy paints a picture of cooperative multilateral relations. Notably, the question of how to establish open dialogue remains. Having assumed chairmanship of the Arctic Council, it is a favorable time to highlight opportunities for sustainable climate action that are aimed at mitigating technological and financial shortfalls. The immediate future will provide an insight into Russia’s intentions, particularly in terms of balancing its economic interest in foreign investment against the desire to retain military security in the region. First and foremost, for this to happen, an appropriate body must address a resumption of military talks and security discussions.

The EU’s Arctic Strategy

The EU first published its Arctic policy in 2009. It has been updated regularly, culminating into its 2016 Joint Communication on an integrated European policy for the Arctic.[46] It focuses on three priorities: Responding to climate change and protecting the environment, promoting sustainable development in the region, and strengthening international cooperation on issues affecting the Arctic. In 2020, the European Commission and the European External Action Service (EEAS) launched a public consultation among EU member states with a rationale to update EU policy in the Arctic. The consultation is part of a process to review priorities and reflect on the EU’s future role in Arctic affairs while producing an updated Arctic Strategy by the end of 2021.[47]

This process presents an opportunity to reflect on the relevance and scope of the current focus areas. As several stakeholders now emphasize security aspects in their respective Arctic strategies, a coherent appreciation of this is called for to adequately address the challenges ahead and to strengthen multilateral cooperation.[48] The goal of the EU’s Arctic security policy is to maintain its status as a conflict-free zone. Combating climate change, protecting the environment, promoting science, innovation, and sustainable development are interrelated EU objectives.

The goal of the EU’s Arctic security policy is to maintain its status as a conflict-free zone.

The input gained will enable informed decision-making on plausible future actions. Moreover, under its chairmanship of the Arctic Council, Russia has implied its openness to international participation. While this may fuel concerns of an assertive Chinese role in the region, it could also be an opportunity for the EU to advocate a security agenda.

EU Perspectives on the Security Relevance of the High North

Developments in the Arctic, particularly the exploration of resources, can challenge peace and stability in the region and beyond. The economic opportunities in the High North have attracted the interest of both Arctic and non-Arctic states, including the EU. However, with potential comes security issues. While there has been little direct engagement on Arctic security affairs, recent trends have sensitized EU officials to various security implications for Europe.[49] Challenges related to security can lead to more cooperation or confrontation among Arctic stakeholders. In the event of conflict escalation, those who are members of the EU or NATO would be required to fulfill their treaty obligations and participate in collective defense. As a result of NATO solidarity obligations, members of the Alliance (Norway, Denmark, Canada, and the US) could find themselves in direct conflict with Russia. Under the EU’s Lisbon Treaty, EU member states have a duty to provide mutual assistance in the event of natural or man-made disasters.[50] This section examines how the EU’s priorities have evolved and how new priorities are defined. More specifically, it investigates whether economic and environmental policies have been secured and whether a convergence exists, which could lead to a more coherent EU policy.

Climate change-related developments in the Arctic region are complex and affect European interests.The pace, scale, and interconnectedness of developments triggered by permafrost warming and increased economic activity require a closer look at the security implications.[51] EU member states play an integral role in stimulating policy developments, including security issues in the High North. While they have broadened their understanding of security, their policies are shaped by a growing awareness that climate change and increased economic activity have implications on security. Security is no longer only limited to the traditional military conflict and territorial defense scenarios, it has been expanded to include human, environmental, and economic dimensions, hence issues such as health, energy, and pollution.[52]

EU member states play an integral role in stimulating policy developments, including security issues in the High North. While they have broadened their understanding of security, their policies are shaped by a growing awareness that climate change and increased economic activity have implications on security.

Rising global demand for energy, combined with shrinking oil and gas reserves, means EU member states are more dependent than ever on imports of natural resources. Energy dependence is expected to rise from 50% in 2000 to 70% in 2030.[53] 24% of total exploited oil and gas resources in the Arctic are consumed by the EU,[54] while Russia and Norway account for the bulk of European gas imports. Against this backdrop, energy security defined as the “availability of sufficient supplies at affordable prices”[55] and the protection of transportation routeshave become critical aspects. Moreover, EU member states are interested in shorter and safer shipping routes to economic boom regions to Asia. The Arctic could become a central energy hub for Europe to diversify energy supplies due to its geographic proximity and largely untapped resources.[56] Besides economic security, the EU is interested in “protecting the environment and local ecology as well as the people and assets from the violence of nature itself”.[57]

At a time when the Arctic geopolitical environment is in flux, awareness of the strategic importance of developments in the region has increased. A coherent strategy to address the causes and effects of climate change is critical.[58] Without high environmental standards for resource extraction, pollution in the Arctic will continue to increase as global demand grows.The EU aims to reduce its environmental impact by promoting renewable, low-carbon energy sources.On that end, it seeks to empower regional authorities to design a climate change agenda alongside sustainable growth so that local communities are involved in climate adaptation planning. It is keen on increasing investment in research, development, and innovation, notably in infrastructure, renewable energy, and sustainable shipping. Expanding and adapting existing EU investment tools to meet the specific needs of Arctic communities, for instance, through quality education and support for the region’s businesses and industries, should help unlock the potential for sustainable growth.Furthermore, it promotes the polluter-pays principle as the basis for all economic activity in the region.The EU’s goal is to facilitate multi-stakeholder and cross-sectoral cooperation. This will allow it to become a more visible player and help ensure peace, stability, and prosperity in the Arctic.

It remains that cooperation must not distract from the scenario of military intervention in the Arctic. The EU needs to be able to position itself in the event of military conflict. It aims to develop joint capabilities and participation in military exercises without escalating tensions. The Arctic can strengthen the EU, not only in economic terms but also in comprehensive security. These perceptions of security dynamics lay the groundwork for a more coherent EU position on the High North.

Outlook & Assessment of EU Priorities and Potential in the Arctic

Arctic protection, sustainable development, and international cooperation have long guided principles for the EU, making it an Arctic player despite lacking formal status in the Council. Strategically, however, a security component is missing. Militarization by superpowers makes it imperative for the EU to include security considerations in its strategic plans for the Arctic.

Two years ago, EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen promised to lead a “geopolitical Commission” to tackle global responsibility for the climate, the economy, health, and security.[59] Unfortunately, the EU does not have much say among Arctic stakeholders, certainly not militarily.[60] Their strategic strength lies in promoting cooperation, sustainable development, and action on climate change – all of which have security implications. Yet security and defense have not been addressed in the EU’s Arctic strategy. Therefore, when updating its Arctic policy, reference to security dimensions would be a logical step.

Since the ongoing crisis in Ukraine, EU-Russian relations have been at an all-time low. It is unclear whether they will remain frozen or whether issue-specific decoupling can be achieved. A forward-looking EU Arctic strategy must treat Russia’s stance for what it is: an ambiguous challenge. Therein lies an opportunity. Where European and Russian interests overlap, cooperation must be sought. While the reasons for the current frozen bilateral relations are tangible, a selective approach to engagement in the Arctic is recommended. The EU needs an Arctic policy that can address the challenges ahead. On that front, it must develop a coherent approach to security and continuously evaluate its role. Inclusive policymaking through coordinated initiatives can contribute to stability in the region.Additionally, promoting ethical and responsible research can help maintain science at the heart of EU decision-making.

Finally, the EU should improve its communication strategy and develop a suitable narrative in relation to its role in the Arctic. Being overexplicit on matters related to defense and security may not be advisable as they are sensitive issues that need to be handled diplomatically.

A forward-looking EU Arctic strategy must treat Russia’s stance for what it is: an ambiguous challenge. Therein lies an opportunity. Where European and Russian interests overlap, cooperation must be sought.

Having said that, the EU’s Arctic policy must be recognized as effective. A strong link between EU climate policy, the European Green Deal, and its updated Arctic Strategy should be established to discourage environmentally unsustainable practices that undermine Arctic ecosystems. Equally, opportunities for green economic growth should be identified and highlighted in its investment priorities. Russia will benefit from climate change as natural resources and sea routes become more accessible. Thus, the EU must do all in its power to promote the arctic ecosystem and gain leeway and concessions. Adopting such policy measures and projecting a global, future-oriented vision of the region is essential to counterbalance the Russian narrative aimed at maintaining the status quo. Nonetheless, the approach must be skillfully implemented and backed by diplomatic efforts.

Cooperation in the Arctic

The Arctic is an emerging geopolitical hotspot. While Russia has taken the first steps to position itself as the dominant power, others will surely follow in suit. For outsiders like the EU who hold a vested interest in sustainable development in the Arctic, it is essential to pursue flexible avenues of cooperation.

Over the past 25 years, the Arctic Council has facilitated peaceful political solutions. It continues to be a critical platform to advance agendas. While issues of military security do not feature, the institutional framework itself was a confidence-building measure.[61]Against this background, it is time for the EU to break new ground and offer forward-looking initiative. The goal should be a multilateral approach towards a rules-based order while avoiding an unfavorable alliance between Russia and China. Channeling cooperation with external actors through the Arctic Council would be a crucial strategic concession by Russia.

The extent to which Arctic exceptionalism can be sustained to avoid conflict remains to be seen. Arctic strategies, including that of the EU, should consider these findings and communicate a concerted vision of its role in the Arctic. The Arctic offers prime opportunities for the EU to promote technological developments as a powerful means of shaping international policy and building a constructive economic partnership with Russia. Here, the potential relies on pragmatic solutions and thus attraction rather than coercion.[62] For effective implementation, coalitions of member states, particularly involving the three in the Council that make use of EU institutional structures, can be a crucial step.

The Arctic offers prime opportunities for the EU to promote technological developments as a powerful means of shaping international policy and building a constructive economic partnership with Russia.

Russia’s strategic objectives in the Arctic are ostensibly defensive but cannot hide Moscow’s decisive approach to asserting power supremacy in the region. While Russia is likely to avoid further escalation, its nuclear capabilities, particularly close to Norway (NATO member) and Finland (EU member), indicate that it is comfortable in a confrontational position and willing to take risks to maintain overall dominance: “Cooperation has achieved little for Russia in the past, but military strength has. In this sense, Russia sees its risk-taking as a strategic advantage over a reluctant West.”[63] However, European policymakers should neither incite Russia’s self-defense discourse nor overreact to claims that Russia and the West are on the brink of war:“Unlike the South China Sea and Taiwan, in the case of the Arctic, it’s up to us [the EU]. We can control the rhetoric, rely on the Arctic Council and European security architecture, and engage in dialogue with Russia.”[64]

Given the growing importance of regional security issues, a framework for structured security dialogueshould be established to increase transparency and prevent misunderstandings that can lead to escalation. Proposals include developing a code of conduct for the Arctic,[65] reactivating the Council’s Arctic Security Forces Roundtable (ASFR) in which Russia has not participated since 2014, and establishing a new working group to address military security issues.[66]

Seeking common ground on security issues within the framework of the NATO-Russia Council is another avenue worth exploring. Although the format has stalled since 2014, it provides an existing framework for moving forward, possibly with US participation. It is the most appropriate format in which to discuss different perspectives on security and develop confidence-building measures for the Arctic.[67]

In the medium to long-term, a new format that provides mechanisms for consultation, not only on military activities but on overall Arctic security, would build trust and promote stability. As an additional step towards building a security architecture, the dialogue could be sought through international conferences such as those organized by the Arctic Circle Assembly or the Munich Security Conference.

However, there is a need to realistically assess the prospect of cooperative security and demilitarization. The Arctic has emerged as the proverbial stage on which Russia attempts to regain superpower status peacefully, in an assertive manner. Although Russia and China are now aligned, the EU should engage in Arctic cooperation to prevent a potential alliance against the West. An established format for dialogue on security would validate military practices through an “Arctic Military Code of Conduct”.[68] This would help create predictable relations and ensure strategic stability. It could well include non-regional actors capable of military operations in the Arctic and provide a non-aggression clause between the signatories.Similar agreements exist in search and rescue and environmental cooperation.

Although Russia and China are now aligned, the EU should engage in Arctic cooperation to prevent a potential alliance against the West.

In summary, the EU needs to establish itself as a critical player in Arctic policy by advocating for environmental standards in resource exploitation as well as intensifying cooperation on Arctic research. Climate change is a key driver of developments in the Arctic and beyond. Russia’s vision of hydrocarbons is “back to the future” and their economic development remains intrinsically linked to the exportation of raw materials.Demand for oil is shrinking and will continue to do so. To avoid compromising its expansionary vision, Russia is interested in the transfer of technology to help mitigate the consequences of climate change. Hence, the EU should seek to pursue joint solutions regarding security, resources, and trade. Climate policy in the Arctic requires leadership, especially as climate security becomes more significant and consensus-building more difficult given the vibrancy of geopolitical polarization. Multilateral initiatives, such as the MOSAiC expedition which involves climate scientists from nineteen nations, provide valuable insights and help build trust. Arctic shipping also requires attention. Arctic sea lanes will compete with southern shipping routes in the future. If prices for oil and gas remain low, the direct and indirect costs of Arctic passages will prove too high.Left to its own devices, Russia cannot raise the necessary funds to exploit resources and effectively develop sea routes in the Arctic. Moscow’s hopes are that the NSR can only materialize with international support. The EU’s Arctic policy offers an opportunity for comprehensive and sustainable cooperation on building regional infrastructure and enabling environmentally sound resource exploitation.Ultimately, cooperation provides hope for future relations between Russia and the EU.

Multilateral initiatives, such as the MOSAiC expedition which involves climate scientists from nineteen nations, provide valuable insights and help build trust.Arctic shipping also requires attention. Arctic sea lanes will compete with southern shipping routes in the future.

Raúl Carbajosa Niehoff is a law graduate from Heidelberg University. During his subsequent Master of International Affairs at the Hertie School in Berlin and the American University, Washington DC, he was an assistant to Ambassador Wolfgang Ischinger at the Munich Security Conference before moving to the German Federal Ministry of Defense. There, he first worked as an assistant to a Parliamentary State Secretary and then as a desk officer at the Directorate-General for Security and Defense Policy. Currently, he is a legal clerk at the Higher Regional Court of Berlin. His research interests are in foreign and security policy with a focus on Eastern Europe. The views expressed in this article are those of the author. They do not necessarily coincide with those of the Federal Ministry of Defense.

[1] Estonian Foreign Intelligence Service, “International Security and Estonia 2021, Public report”, 2020, 2, Tallinn, https://www.valisluureamet.ee/pdf/raport/2021-ENG.pdf.

[2] Disclaimer: “Europe” refers to all continental NATO and EU members, including the United Kingdom.

[3] Kristi Raik, “Russia”, in: “Stronger Together: A Strategy to Revitalize Transatlantic Power”, 45, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs in cooperation with German Council on Foreign Affairs (DGAP), https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/Transatlantic/StrongerTogether.pdf.

[4] Sabine Fischer, “Vom Getriebenen zum Gestalter: Russland in internationalen Krisenlandschaften”, in: Perthes, Volker (ed.) “Ausblick 2017: »Krisenlandschaften« Konfliktkonstellationen und Problemkomplexe internationaler Politik“, 31-32, SWP-Studie, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik Deutsches Institut für Internationale Politik und Sicherheit, January 2017, Berlin, https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/studien/2017S01_ild.pdf.

[5] Defined as the latitude at which the sun does not set for 24 hours on the summer solstice (66° 33’ N), Jörg-Friedhelm Venzke, “Die Arktis und ihre Grenzen: Eine physisch-geographische Einführung,“ in: Jose Lozán, Hartmut Grassl, Peter Hupfer, Dieter Piepenburg (eds.), “Warnsignal Klima: Die Polarregionen,“. 11-14, Hamburg, Verlag Wissenschaftliche Auswertungen; see map of the Arctic region.

[6] Michael Paul, “Arktische Seewege: Zwiespältige Aussichten im Nordpolarmeer,“ 7, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP), SWP-Studie 14, https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/studien/2020S14_Arktis.pdf.

[7] Timothy Heleniak, Dimitri Bogoyavlensky, “Arctic Populations and Migration,” in: Joan Larsen, Gail Fondahl (eds.), “Arctic Human Development Re-port. Regional Processes and Global Linkages,” 53-58, http://norden.diva-portal.org.

[8] Page Wilson, “Society, steward or security actor? Three visions of the Arctic Council,” in: Cooperation and Conflict, 51(1) (23015), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0010836715591711.

[9] German Arctic Office (2020) “Arktis und Antarktis – mehr Unterschiede als Gemeinsamkeiten?”, 2, Alfred-Wegener-Institut Helmhotz-Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung (AWI), May 2020, Potsdam, https://www.arctic-office.de/fileadmin/user_upload/www.arctic-office.de/PDF_uploads/FactSheet_Arktis-Antarktis_Deutsch_web.pdf.

[10] For 50 years, the Arctic has been warming more than twice as fast as the rest of the globe. This phenomenon of “Arctic amplification” has to do with feedback processes, such as the ice-albedo effect, triggered by the retreat of Arctic sea ice, which leads to less sunlight reflection. The Arctic Ocean could be ice-free ice in summer as early as the late 2030s, Endnote 25, 4-5.

[11] Heather A. Conley, “Arctic Economics in the 21st Century: The Benefits and Costs of Cold,” 33, A Report of the CSIS Europe Program (2013), Maryland Lanham: Row-man & Littlefield, Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 2013, https://www.csis.org/analysis/arctic-economics-21st-century.

[12] Michael Paul, “Arktische Seewege: Zwiespältige Aussichten im Nordpolarmeer,“ 5, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP), SWP-Studie 14, https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/studien/2020S14_Arktis.pdf.

[13] Founded in 1996 with the Ottawa, it dates to Mikhail Gorbachev’s 1987 vision that the Arctic must be maintained as a zone of peace for humanity, Gunter Görner, “Ein Beispiel konstruktiver internationaler Zusammenarbeit: 60 Jahre Antarktis-Vertrag,“ in: “Welt Trends: Das außenpolitische Journal“, 58-65, Potsdamer Wissenschaftsverlag, https://shop.welttrends.de/e-journals/e-paper/2019-quo-vadis-europ%C3%A4ische-union/ein-beispiel-konstruktiver-internationaler.

[14] As US condition, military matters were excluded. Instead, the Security Forces Roundtable was established, but it has been meeting without Russia since 2014, Congressional Research Service (2021) “Report for Congress, Changes in the Arctic: Background and Issues for Congress,” 56-57, 1 February 2021, Washington D.C., https://crsreports.congress.gov/.

[15] The 13 observer states are China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Poland, the Republic of Korea, Singapore, Spain, Switzerland, UK. The EU has been denied observer status, Helga Haftendorn, Helga, “The Case for Arctic Governance. The Arctic Puzzle,“ 16, Reykjavik: Centre for Arctic Policy Studies, 2013, https://ams.hi.is/en/publication/24/.

[16] Arctic Council, “Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment (AMSA) 2009 Report,” 16, April 2009, https://www.pmel.noaa.gov/arctic-zone/detect/documents/AMSA_2009_Report_2nd_print.pdf.

[17] Janis Kluge, Michael Paul, “Russia’s Arctic Strategy through 2035: Grand Plans and Pragmatic Constrains,” in: SWP-Aktuell Nr. 89, November 2020, https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2020C57/.

[18] Alexander Bratersky, “Russia’s Arctic activity to increase with fresh strategy and more capability tests,” in: DefenseNews, 11 April 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/smr/frozen-pathways/2021/04/11/russias-arctic-activity-to-increase-with-fresh-strategy-and-more-capability-tests/.

[19] European Commission, “Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council. An integrated European Union policy for the Arctic,” 27 April 2016, https://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/arctic_region/docs/160427_joint-communication-an-integrated-european-union-policy-for-the-arctic_en.pdf.

[20] Iona Mackenzie Allan, “Arctic Narratives and Political Values: Arctic States, China and NATO,” 56-59, NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, May 2020, https://www.stratcomcoe.org/arctic-narratives-and-political-values-arctic-states-china-and-nato-0.

[21] The great majority of Russian gas, nickel, diamonds, and rare earth metals are extracted in Russia’s Exclusive Economic Zone in the Arctic, Ekaterina Klimenko, “Russia’s new Arctic policy document signals continuity rather than change,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), 6 April 2020, https://sipri.org/commentary/essay/2020/russias-new-arctic-policy-document-signals-continuity-rather-change.

[22] Roger Howard, “Russia’s New Front Line,” in: Survival, 52 (2010), 146, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00396331003764678?journalCode=tsur20.

[23] Iona Mackenzie Allan, “Arctic Narratives and Political Values: Arctic States, China and NATO,” 57, NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, May 2020, https://www.stratcomcoe.org/arctic-narratives-and-political-values-arctic-states-china-and-nato-0.

[24] Agne Cepinskyte, Michael Paul, “Großmächte in der Arktis: Die sicherheitspolitischen Ambitionen Russlands, Chinas und der USA machen einen militärischen Dialog erforderlich,“ in: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, SWP-Aktuell 50, 2, Juni 2020, https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/aktuell/2020A50_Arktis_web.pdf.

[25] International Expert Council on Cooperation in the Arctic (IECCA) (2013), “The development strategy of the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation,” http://www.iecca.ru/en/legislation/strategies/item/99-the-development-strategy-of-the-arctic-zone-of-the-russian-federation.

[26] Congressional Research Service (2021) “Report for Congress, Changes in the Arctic: Background and Issues for Congress,” 1, 1 February 2021, Washington D.C., https://crsreports.congress.gov/.

[27] European Commission, “Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council. An integrated European Union policy for the Arctic,” 27 April 2016, https://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/arctic_region/docs/160427_joint-communication-an-integrated-european-union-policy-for-the-arctic_en.pdf.

[28] To date, only about 2 percent of the world’s trade takes place via Arctic sea routes. Extreme weather conditions, limited rescue capacity, disputed waters, and the fact that less than 5 percent of the Arctic is adequately mapped make navigation too costly and dangerous, James Stavridis, “Sea Power. The History and Geopolitics of the World’s Oceans,” 239, Penguin Press, New York.

[29] The route extends across the Barents Sea to Iceland through the “GIUK gap” between Greenland, Iceland and the northern tip of the UK. To ensure sea-based nuclear second-strike capability, freedom of movement of Russian nuclear submarines into the Atlantic is essential. Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, “Russian Nuclear Forces,” in: Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 102-110, 76 (2020) 2, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00963402.2020.1728985.

[30] Rolf Tamnes, “The High North: A Call for Competitive Strategy,” in: John Andreas Olsen (ed.), Security in Northern Europe: Deterrence, Defence and Dialogue, 8, London: Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) (Whitehall Paper 93), October 2018.

[31] Agne Cepinskyte, Michael Paul, “Großmächte in der Arktis: Die sicherheitspolitischen Ambitionen Russlands, Chinas und der USA machen einen militärischen Dialog erforderlich,“ in: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, SWP-Aktuell 50, 7-8, Juni 2020, https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/aktuell/2020A50_Arktis_web.pdf.

[32] Mathieu Boulègue, “Russia’s Military Posture in the Arctic”, 6-11, 28 June 2019, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2019/06/russias-military-posture-arctic.

[33] The exercise with up to 50 ships and 40 aircraft had the objective to block sea routes and deny space to strengthen Russia’s presence in the Arctic and defend its resources. Endnote 10.

[34] Alec Luhn, “Russian Submarines Power into North Atlantic in Biggest Manoeuvre since Cold War,” The Telegraph, 30 October 2019, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2019/10/30/russian-submarines-power-north-atlantic-biggest-manoeuvre-since/.

[35] Valery Gerasimov, “Briefing for foreign military attachés,” official site of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation, https://eng.mil.ru, 24 December 2020. https://eng.mil.ru/en/news_page/country/more.htm?id=12331668@egNews.

[36] Gilbert Rozman, “The Sino-Russian Challenge to the World-Order,” 267, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

[37] It accounts for about a third of the Federation’s territory, Friedbert Pflüger, Arash Duero, “A New Challenge: Climate Security: The Geopolitical Implications of Climate Change,” in: “International Security Forum Bonn 2019,” 56, Bonn University, Center for Advanced Security, Strategic and Integration Studies (CASSIS), https://www.cassis.uni-bonn.de/de/dateien/international-security-report-2020/ISFB%20Report%202019.pdf.

[38] Iona Mackenzie Allan, “Arctic Narratives and Political Values: Arctic States, China and NATO,” 109, NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, May 2020, https://www.stratcomcoe.org/arctic-narratives-and-political-values-arctic-states-china-and-nato-0.

[39] Agne Cepinskyte, Michael Paul, “Großmächte in der Arktis: Die sicherheitspolitischen Ambitionen Russlands, Chinas und der USA machen einen militärischen Dialog erforderlich,“ in: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, SWP-Aktuell 50, 3, Juni 2020, https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/aktuell/2020A50_Arktis_web.pdf.

[40] Congressional Research Service (2021) “Report for Congress, Changes in the Arctic: Background and Issues for Congress,” 60, 1 February 2021, Washington D.C., https://crsreports.congress.gov/.

[41] Heather A. Conley, Caroline Rohloff, “The New Ice Curtain: Russia’s Strategic Reach to the Arctic,” 7, Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS).

[42] Pavel Devyatkin, “Russia’s Arctic Strategy. Aimed at Conflict or Cooperation?,” 6-7, Washington, D.C.: The Arctic Institute, 6 February 2018, https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/russias-arctic-strategy-aimed-conflict-cooperation-part-one/.

[43] Last reassured by President Putin at the G20 summit in Osaka in June 2019. Friedrich Schmidt, “Russlands Klimapolitik: Putin und Greta,” FAZ, 5 October 2019, https://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/ausland/putin-und-greta-warum-russland-den-klimawandel-nun-als-risiko-erkennt-16416969.html.

[44] In the last ten years, Russia has increased coal production by more than 30 percent to 440 million tons per year. It is the world’s third-largest producer, Atle Staalesen, “Chinese Money for Northern Sea Route,” The Barents Observer, 12 June 2018, https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/arctic/2018/06/chinese-money-northern-sea-route.

[45] Almost 60 percent of Russia’s exported raw materials are extracted in Siberia. The Arctic holds 80 percent of Russia’s natural gas. Moscow Times (2020), “Russia Unveils Arctic Ambitions With 2032 Strategy,” 6 March 2020, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2020/03/06/russia-unveils-arctic-ambitions-with-2035-strategy-a69543.

[46] European Commission, “Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council. An integrated European Union policy for the Arctic,” 27 April 2016, https://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/arctic_region/docs/160427_joint-communication-an-integrated-european-union-policy-for-the-arctic_en.pdf.

[47] Of 140 received contributions from representatives of 17 EU Member States and nine non-EU Member States, 25% belonged to civil society, 21% academia and research institutions, 17% public authorities, 12% business associations, and 10% NGOs. European Union (EU) (2021) “Summary of the results of the public consultation on the EU Arctic policy,” 5, Publications Office of the EU, January 2021, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/497bfd35-5f8a-11eb-b487-01aa75ed71a1.

[48] Michael Mann, “A New EU Arctic Strategy: Virtual Workshop with EU Ambassador Michael Mann,” 24 November 2020, https://www.arctic-office.de/en/forums-and-events/a-new-eu-arctic-strategy-virtual-workshop-with-eu-ambassador-michael-mann/.

[49] Javier Solana, Benita Ferrero-Waldner, “Climate Change and International Security. Paper from the High Representative and the European Commission to the European Council,” 8, S113/08, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/reports/99387.pdf.

[50] Claudia Major, Stefan Steinicke, “EU Member States’ Perceptions of the Security Relevance of the High North,” 12, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, October 2011, https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/arbeitspapiere/wp_mjr_ste_Geonor_Oktober_2011.pdf.

[51] Alyson J.K. Bailes, “Options for closer Cooperation in the High North: What is needed?,” in: Sven G. Holtsmark, and Brooke A. Smith-Windsor (ed.), “Security prospects in the High North: geostrategic thaw or freeze,” 41-42, Nato Defence College Forum Paper 7, Rome 2009, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/102391/fp_07.pdf.

[52] Christoph O. Meyer, “The Purpose and Pitfalls of Constructivist Forecasting: Insights from Strategic Culture Research for the European Union’s Evolution as a Military Power,” 9, International Studies Quarterly, volume 55, https://academic.oup.com/isq/article/55/3/669/1829885?login=true.

[53] European Commission (2000), “Green Paper: Towards a European Strategy for the Security of Energy Supply,” 20-25, 29 November 2000, Publications Office of the EU, https://op.europa.eu/es/publication-detail/-/publication/0ef8d03f-7c54-41b6-ab89-6b93e61fd37c/language-en.

[54] Sandra Cavalieri et al, “Spurensuche. Der ökologische Fußabdruck der EU in der Arktis,“ in: Osteuropa: Logbuch Arktis, Der Raum, Interessen und das Recht, 217, February/March 2011, Jg. 2-3, https://www.ecologic.eu/4079.

[55] Daniel Yergin, “Ensuring Energy Security,” 70, Council on Foreign Relations, Foreign Affairs, 85, March/April 2006, 2, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20031912.

[56] Maritime trade between Europe and Asia accounts for 26% of total transcontinental ship traffic. However, the advantages of a shorter sea route through the Arctic are still offset by the unpredictability of the ice and inadequate rescue capacities. James Rogers, “From Suez to Shanghai. The European Union and Eurasian Maritime Security,” 22, Paris: EUISS, Occasional Paper No. 77, March 2009, https://www.iss.europa.eu/content/suez-shanghai-european-union-and-eurasian-maritime-security.

[57] Alyson J.K. Bailes, “Options for closer Cooperation in the High North: What is needed?,” in: Sven G. Holtsmark, and Brooke A. Smith-Windsor (ed.), “Security prospects in the High North: geostrategic thaw or freeze,” 37, Nato Defence College Forum Paper 7, Rome 2009, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/102391/fp_07.pdf.

[58] European Union (EU) (2021) “Summary of the results of the public consultation on the EU Arctic policy,” 2-4, Publications Office of the EU, January 2021, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/497bfd35-5f8a-11eb-b487-01aa75ed71a1.

[59] Mark Leonard, “The EU’s Double Bind,” Internationale Politik Quarterly, 6 January 2021, https://ip-quarterly.com/en/eus-double-bind.

[60] For now, “we [the EU] are not a hard security provider, and we have nothing approaching a European army.” Michael Mann, “A New EU Arctic Strategy: Virtual Workshop with EU Ambassador Michael Mann,” 24 November 2020, https://www.arctic-office.de/en/forums-and-events/a-new-eu-arctic-strategy-virtual-workshop-with-eu-ambassador-michael-mann/.

[61] Volker Perthes, “Arktische Kooperation trotz europäischen Frosts,” Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP), 9 May 2014, Berlin, https://www.swp-berlin.org/swp-zeitschriftenschau/kurz-gesagt/arktische-kooperation-trotz-europaeischen-frosts/.

[62] Henrik W. Ohnesorge, “A Fatal Neglect: On the Significance of U.S. Soft Power Today,” in: “International Security Forum Bonn 2019,” 72, Bonn University, Center for Advanced Security, Strategic and Integration Studies (CASSIS), https://www.cassis.uni-bonn.de/de/dateien/international-security-report-2020/ISFB%20Report%202019.pdf; Stefan Mair, “Kriterien für die Beteiligung an Militäreinsätzen,” in: Stefan Mair (ed.), “Auslandseinsätze der Bundeswehr. Leitfragen, Entscheidungsspielräume und Fragen,” 13-14, SWP-Studie, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, September 2007, Berlin, https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/studien/2007_S27_mrs_ks.pdf.

[63] Pavel K. Baev, in Paul C. Strobel, “Die Arktis: Ein neues Konfliktgebiet?,“ 2, Reservistenverband „Wir sind die Reserve,“ 2 March 2021, https://www.reservistenverband.de/magazin-die-reserve/die-arktis-ein-neues-konfliktgebiet/.

[64] Philippe Welti, in: Paul C. Strobel, “Die Arktis: Ein neues Konfliktgebiet?,“ 4, Reservistenverband „Wir sind die Reserve,“ 2 March 2021, https://www.reservistenverband.de/magazin-die-reserve/die-arktis-ein-neues-konfliktgebiet/.

[65] Mathieu Boulègue, “Russia’s Military Posture in the Arctic”, 30, 28 June 2019, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2019/06/russias-military-posture-arctic.

[66] Tømmerbakke Gulliksen, Siri (2019), “Why Finland and Iceland want security politics in the Arctic Council,” Arctic Today, 25 October 2019, https://www.arctictoday.com/why-finland-and-iceland-want-security-politics-in-the-arctic-council/.

[67] Reiner Schwalb, “Wege aus der Krise?,“ Michael Staack, Gunther Hauser, “Russland und der Westen – Ist kooperative Sicherheit möglich?,“ 16, Wissenschaftliches Forum für Internationale Sicherheit e.V., JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1bvndmb.4.

[68] Agne Cepinskyte, Michael Paul, “Großmächte in der Arktis: Die sicherheitspolitischen Ambitionen Russlands, Chinas und der USA machen einen militärischen Dialog erforderlich,“ in: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, SWP-Aktuell 50, 7, Juni 2020, https://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/aktuell/2020A50_Arktis_web.pdf.