Abstract: This paper explores the persistent tensions within U.S. security cooperation, where efforts to build partner capacity often collide with the realities of sovereignty, hierarchy, and risk. Although designed to enhance global stability, security cooperation initiatives frequently impose on partner autonomy, revealing the hierarchical nature of the international system beneath the rhetoric of equal partnership. Drawing from strategic theory and operational experience, the paper introduces the “security cooperation dilemma,” highlighting the twin fears of entrapment for the dominant power and abandonment for the partner. It criticises existing Department of Defense (DOD) frameworks, especially the Significant Security Cooperation Initiative Construct (SSCIC), for inadequately addressing political willingness and absorptive capacity. The analysis argues that political commitment is a function of risk, particularly physical and political, and should be observed through tangible actions rather than verbal assurances. The study concludes by advocating for a recalibration of security cooperation practices, emphasising strategic patience, realistic timelines, and a rigorous focus on genuine political commitment and risk absorption as prerequisites for sustainable security cooperation success.

Problem statement: How can security partners account for the security cooperation dilemma in an international system rife with unknown risks while ensuring effective and mutually beneficial security partnerships?

So what?: Strategic assessments that underpin security cooperation initiatives tend to emphasise narrative coherence over predictive utility, leading to a disconnect between planning assumptions and on-the-ground realities. Instead, an operational assessment, not of what the partner lacks, but what the partner can provide to the project, should be instituted. This flips current Department of Defense security cooperation practice on its head, with its emphasis on filling capability gaps. Planning should focus on tangible deliverables by the partner that would demonstrate commitment through political risk.

Source: shutterstock.com/Sergey Kohl

Introduction

The concepts of sovereignty, anarchy and hierarchy are a paradox which sits at the heart of America’s global security enterprise—and it demands closer examination. Security cooperation is often seen as a benign extension of U.S. power, a way to build a more stable and friendly world without the costs of direct intervention. Behind the rhetoric of security lies a fundamental tension: to protect its own interests, the United States must craft security solutions that prioritise itself, yet in a way that accounts for the partner’s security interests. The United States provides security assistance to partners around the world to protect its interests, citizens and territory from external threats, such as invasion, terrorism, or attacks on critical infrastructure. Sharing security ensures the U.S. can pursue its economic, political, and strategic interests globally. This includes maintaining access to vital resources, protecting trade routes, and supporting allies. As a major global power, the U.S. has an interest in promoting a stable international order. This helps to prevent conflicts, promote economic development, and uphold human rights. A strong security posture serves as a deterrent to potential adversaries, discouraging them from taking aggressive actions that could threaten U.S. interests. The U.S. seeks to maintain its position as a global leader. However, problems arise as the United States creates partnerships to extend its influence and power around the world in an attempt to maintain its position as a global leader.

The United States provides security assistance to partners around the world to protect its interests, citizens and territory from external threats, such as invasion, terrorism, or attacks on critical infrastructure.

The Role of Security Cooperation?

Security cooperation, a form of security assistance planned and executed by the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD), is a function of that power extension. It includes combined exercises, training exchanges, dialogues, and other interactions between U.S. and partner nation military forces.[1] Security cooperation is based on the idea of mutual benefit, where both the U.S. and its partners gain from the relationship.[2] It is a long-term endeavour aimed at building enduring partnerships. Some security cooperation programs are designed to provide equipment and training, tailored to the specific needs and capabilities of each partner nation. The U.S. respects the sovereignty of its partners and works with them as equals, but policy and law are clear: U.S. interests must take priority. So, accounting for the security cooperation dilemma is paramount if the U.S. is to ensure that the security cooperation initiative is also in the partner’s interests. This tension in applied international relations sets up a demonstration of the security cooperation dilemma.

Security cooperation is based on the idea of mutual benefit, where both the U.S. and its partners gain from the relationship.

The Dilemma of Security Cooperation

The security cooperation dilemma arises from two competing fears: For the dominant power, entrapment, or the fear of being dragged into a conflict by an overly adventurous ally or partner, weighs heavily, since conflict appears to be endemic in the system. For the partner, it is abandonment, the fear of not receiving support from allies when needed.[3] Glenn Snyder argued that these agreements (Snyder called them alliances), while formed for mutual security, also create a security dilemma for their members.[4] This idea has particularly pernicious effects in the world of security cooperation. The partners most in need of security guarantees exist in some of the most unstable parts of the globe.[5] According to the Upsala conflict data, 96% of the extant conflicts occur inside states and hence outside the theorising of normative international relations, which is concerned with the relationships between states. The security cooperation dilemma is one of the most vexing problems faced by the U.S. in the 21st century. States operate in an international system without a central authority, making them inherently distrustful of each other’s intentions. This can lead to an arms race, escalating tensions, and even conflict, even if none of the states actually desire such an outcome.

Three Forces Underpinning the Dilemma

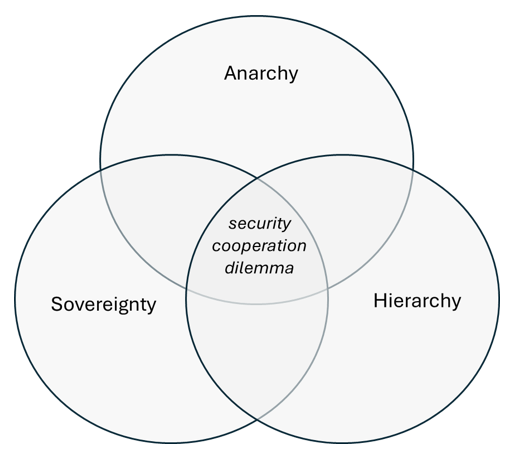

Three forces in the system define the dilemma of cooperation: Anarchy, hierarchy, and sovereignty. They operate within an international system that is already a complex web of relationships, interactions, and structures connecting and shaping the behaviour of states and other actors on the global stage.

The first force, anarchy, is the weakest of the three. Fear of anarchy characterises the international system and greatly influences the security choices of states. Fear is the fundamental driver of the security dilemma. States, especially in an anarchic international system, often fear the intentions of others and take actions to protect themselves, which can be perceived as threatening by others. The idea of the absence of a central authority or world government to enforce rules and resolve disputes is as old as the Peloponnesian war.[6] There is no judge or global 911 to call in the event of invasion or rebellion. Under anarchy, all help is self-help.[7]

The Three Forces that Influence the Security Cooperation Dilemma, Anarchy is the Weakest and Hierarchy is the Strongest; Source: author.

State sovereignty is a stronger force, and a surprisingly new entrée into security conceptualisation.[8] Empires have been the central organ of the international system for much longer. The idea of state sovereignty began with the liberalisation of the ancien régime in the 18th century. Dominant groups no longer control others’ security and economic interests to their own end. To be sovereign, a state must possess supreme authority within its borders and be independent of external control. It has the right to make its own decisions without interference from other states.[9] Another component of sovereignty is that other states recognise a state as a legitimate member of the international community. This recognition allows it to participate in international relations and engage in diplomatic activities. While the concept of sovereignty is the least understood component of the security dilemma that faces states,[10] fundamentally, strategies of security cooperation are impositions on the sovereignty of partners. Anarchy drives states to accept the requirement of a political solution to security.

State sovereignty is a stronger force, and a surprisingly new entrée into security conceptualisation.

Hierarchy is the strongest force, with some states exercising influence over others.[11] The existence of hierarchy challenges the traditional view of international relations as purely anarchic, where all states are considered equal.[12] It acknowledges that there are degrees of power and influence among states, leading to relationships that resemble those of authority and subordination in domestic settings. The system is hierarchical with mechanisms to maintain stability–the balancing theories of international relations attest to this. Hierarchies provide a degree of stability and predictability to the international system, reducing the likelihood of major power conflict. In hierarchies, the hegemonic state takes on the security concerns of the client state. In effect, the client state becomes the agent of the hegemon; ipso facto, the client loses sovereignty when it accepts security guarantees from another state. The hierarchical nature of the order implies that the United States, as the leading power, bears a disproportionate share of the costs of maintaining the system, while other states benefit from its stability and security provisions.[13] The growth of systemic interconnectedness leads to increasing interdependence and vulnerability.[14] As a dominant power, the United States would have a strong stake in maintaining a hierarchy with itself at the top. [15] Under hierarchy, the distribution of power, and its implications for security cooperation and global influence, is immense.

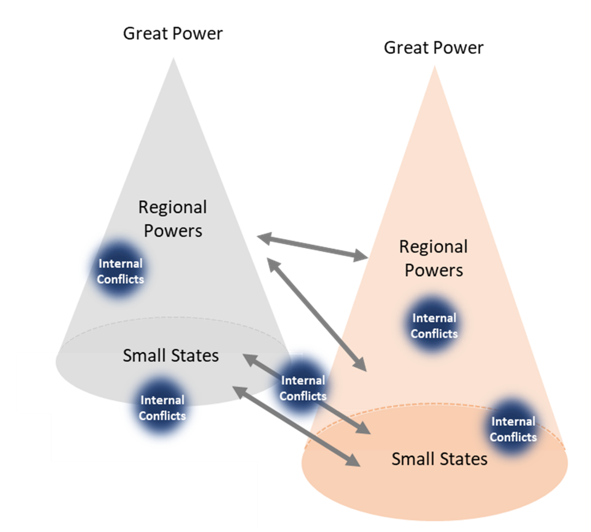

Conflict is endemic to the international system, as explained by traditional IR theories. Great powers at the top rarely go to war with each other and haven’t since 1945. States lower in the system engage in war and are involved in many internal conflicts, which then become internationalised by the dominant powers. Source: W. Reynolds, Ouroboros: Understanding the War Machine of Liberalism. Lexington Books, 2019.

The forces work on each other in a way that creates the security cooperation dilemma. Anarchical systems are unstable; hierarchy stabilises the system, and small states seek hierarchy to offshore their own security. However, the demands of sovereignty, particularly in developing countries, require states to at least act independently. Sometimes, pressure to avoid security colonisation can lead weak states to throw off security agreements.

In hierarchical systems, for both the dominant power and the receiving partner, risk comes from instability, not from conflict. The greater powers, of which the U.S. is most active, tamp down the ambitions of states to invade or influence other states.[16] For countries like the U.S. that exercise hegemonic ambitions, security hierarchy is meant to stabilise parts of the international system. Seeking stability is what leads the would-be hegemon to intervene in other states’ affairs. This makes the partner’s sovereignty a lesser concern than the security goal. This logic creates a vast blank space into which the burden of the security cooperation dilemma attacks unaware. Under anarchy, weak states must have security guarantees. Under hierarchy, a state gives up a portion of its sovereignty in return for guarantees from the hegemon. This is the security cooperation dilemma, which poses political risk to both the security-providing partner and the security-receiving partner. Accounting for that risk is a paramount concern.

In hierarchical systems, for both the dominant power and the receiving partner, risk comes from instability, not from conflict.

Risk in Security Cooperation

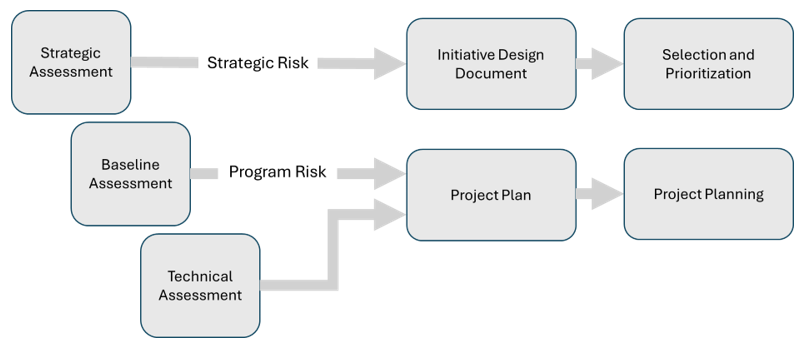

The United States provides an immense amount of security aid through its security cooperation activities. The DOD attempts to account for the security cooperation dilemma through analysis of risk in the Significant Security Cooperation Initiative Construct (SSCIC).[17] The product of the SSCIC is the initiative design document (IDD), which captures analysis of the operating environment.[18] DOD uses the IDD to synchronise and sequence activities and to identify risks to positive outcomes from the implementation of the security cooperation activity.

The strategic assessment required for DOD prioritisation and selection is created and very different from the baseline assessment required by the statute. Strategic risk, where the security cooperation dilemma lies, is addressed in the strategic assessment; Source: author.

The required strategic assessment is a function of the geographic combatant command’s campaign assessment. This ensures that the SSCIC program is nested within the regional campaign plan, which is nested within U.S. national strategic direction and guidance.[19] The six commands identify yearly objectives (most activities are planned over five years), indicators of success, the partner’s ability to absorb and sustain the grant, risks to favourable outcomes, political willingness to undertake the security activity, accountability, and constraints on the partner’s ability to support U.S. goals.[20] This is an incredibly complex undertaking for many reasons: (1) the environment of the partner is difficult to understand, (2) security institutions are naturally reluctant to reveal their own processes, and (3) little authority is held at the level of the project in many developing countries. At the strategic level, the interactions of contextual variables make descriptive analysis, much less predictive analysis, impossible. Because of these weaknesses, the DOD strategic assessment focuses on creating a value narrative to facilitate selection and high prioritisation. Very quickly, the usefulness of the IDD in describing risk in cooperation drops off.

The Three Forces in Security Cooperation

Assessing risk to security cooperation initiatives means the DOD must assess the risk of the security cooperation dilemma to partners. It is vitally important to understand the relationship between the forces of the dilemma and political commitment and willingness. Political commitment begins with physical risk. Life-threatening situations, where there is a real chance of physical death, drive political will. Anarchy and its incipient destructions forces the partner into the political process. Acceptance of hierarchy translates risk through the mechanism of state survival. Political willingness is a derivative of risk. If there is a high risk, there is high motivation to accept political limits to sovereignty. For example, in the case of Ukraine, political commitment to receiving and integrating military equipment and training from the West is very high. In the case of a partner under no direct threat, additional incentives to commit to change may be necessary.

Assessing risk to security cooperation initiatives means the DOD must assess the risk of the security cooperation dilemma to partners.

Judging the efficacy of lasting commitment to the hierarchisation of security cooperation is the bête noire of security cooperation. After all, tens of millions of dollars were spent on Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali.[21] Political commitment is really a political skill that is operationalised as the use of influence in an organisation to move toward a goal.[22] Influence behaviours are visible, and political skill is predicated on a leader’s willingness to deploy influence and try to influence others.[23] Autocratic regimes value silence, not innovation, so there is pressure to remain hidden, and public discourse is discouraged. Public opinion also affects political will. Since public opinion is often a function of framing, this is an important perspective to keep in mind since specific identities and ethnicities are overrepresented in many partner governance institutions. When there are security issues, conflict, or violence, the affected population may hold strong opinions on the issue, but the ruling class may not.[24] This could be a significant issue with developing partners with less than robust public discourse, media, and civil-military relations. Political willingness can be very high if there is no political risk. Political commitment, in the sense of security, comes from the very real possibility of death.[25] Political commitment to security cooperation goals increases with the increased risk of physical violence.

The Political in Security Cooperation

The political aspect of security cooperation is a measure of willingness and ableness to achieve security goals through hierarchisation. Willingness is a mix of motivation to fix the problem, the intensity of those feelings, and salience, which is perceived as importance to the decision-maker. In other words, is the decision maker willing to take political risks to make the change? The higher the risk, the greater the political willingness. Inversely, if there is no risk, there is no political willingness. If the program fails, the decision maker won’t care because they didn’t risk anything. Absorptive capacity can be seen as another component of political commitment.

In this quadrant, low risk can deliver false commitment since no physical risk and no political capital needs be expended if the security capability is Title 10 grant assistance; Source: author.

Capacity, or ableness, is political commitment operationalised to make changes in the partners’ security culture to the benefit of the U.S. As political commitment increases, the latent power to create real change increases. Partners will find the tools to commit to change. Passing budgets, increasing pay and recruitment, changing promotion systems from nepotistic to merit-based are indicators of an increasing acceptance of political risk. As real changes in the security partner’s institutions take hold, political risk increases. As political risk increases, commitment to those changes increases. Conversely, the dominant partner increasing the cooperation requirements could lead to a lessening of political commitment. Conditionality, the concept of attaching conditions to security assistance, would have an adverse effect on commitment.[26] As the burden of requirements increases, the partner may seek security guarantees from other potential partners. Thus, from physical risk, we move to political risk and find partners willing to submit to the hierarchisation required for shared security interests.

Conclusion

This security cooperation dilemma is not merely an academic concern. Anarchy, sovereignty and hierarchy, in all their forms, affect positive outcomes for U.S. security. The tension between these forces often manifests in donor-driven programming, partner ambivalence, and ultimately, fragile security reforms. Security cooperation, at its core, is an exercise in navigating these inherent contradictions.

The U.S. Congress requires demonstrable political commitment on the part of the partner. This is much more than a verbal commitment received at the conference table. Since a few countries would turn down free equipment and training provided by grant assistance, simple acceptance of equipment cannot mean political commitment.[27] The DOD’s planning frameworks, including the Significant Security Cooperation Initiative Construct (SSCIC) and the Initiative Design Document (IDD), attempt to formalise risk assessments but often fall short. The strategic assessments that underpin these initiatives tend to emphasise narrative coherence over predictive utility, leading to a disconnect between planning assumptions and on-the-ground realities. Instead, an operational assessment of what the partner can provide to the activity should be attempted. This flips current DOD security cooperation practice on its head, with its emphasis on filling capability gaps. DOD planning should focus on tangible deliverables by the partner that would demonstrate commitment through political risk. Most important, it is an actual activity plan that lays out what the partner is expected to do along an agreed-upon timeline. While this is a form of conditionality, it is weak conditionality, predicated not on transformational goals, but on practical boots-on-the-ground realignment of units, equipment, and money that matches the inputs of U.S. grant assistance.

The DOD’s planning frameworks, including the Significant Security Cooperation Initiative Construct and the Initiative Design Document, attempt to formalise risk assessments but often fall short.

Addressing the security cooperation dilemma requires a recalibration of expectations and practices. First, political commitment must be treated not as a rhetorical assurance but as an observable phenomenon, reflected in partners’ willingness to incur real political and institutional risk. Second, program designs must be anchored in realistic timelines that account for the slow, contested nature of institutional reform. Third, the United States must resist the temptation to impose overly ambitious conditionalities that may erode partner commitment rather than strengthen it. Ultimately, successful security cooperation rests on recognising that sovereignty, while rhetorically respected, is practically compromised in any hierarchical relationship. The goal should not be to eliminate this tension—an impossible task—but to manage it with greater humility, realism, and strategic patience. By focusing on political willingness, genuine risk-taking, and absorptive capacity as foundational elements, the United States can more effectively navigate the security cooperation dilemma and build more resilient, stable partnerships in an increasingly fragmented world.

Phil W. Reynolds, PhD. Is a professor of security cooperation in the U.S. Department of Defense. His research interests are power cycle theories; irregular and asymmetric conflicts; and critical IR. Dr. Reynolds’ work has appeared in Real Clear Defense, the Cypher Brief, and the Journal of Strategic Security. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. government.

[1] U.S. Army. Security Cooperation Lessons and Best Practices Bulletin: March 2016, Army Publishing Directorate, March 2016, https://api.army.mil/e2/c/downloads/2023/01/19/7d7e0e33/16-09-security-cooperation-lessons-and-best-practices-bulletin-mar-16-public.pdf.

[2] Robert Schafer, Brandon Denecke, Richard Merrin, Matthew Hughes, Aaron Malcolm, Chris Mullis, James Brown II, Curt Belohlavek, L.H. Ginn, Jacob Gibson, Ryan Johnson, Understanding Security Cooperation, No. 25-01. Fort Leavenworth, KS: Center for Army Lessons Learned, October 17, 2024, https://api.army.mil/e2/c/downloads/2024/10/17/faf2497c/no-25-01-768-understanding-security-cooperation-oct-24.pdf.

[3] Glenn H. Snyder, “The Security Dilemma in Alliance Politics,” World Politics 36, no. 4 (1984): 461–495. For a different perspective, see John J. Mearsheimer, “Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault: The Liberal Delusions That Provoked Putin,” Foreign Affairs, August 18, 2014, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russia-fsu/2014-08-18/why-ukraine-crisis-west-s-fault. For a fun explanation of Mearsheimer’s critique, read Isaac Chotiner, “Why John Mearsheimer Blames the U.S. for the Crisis in Ukraine,” The New Yorker, March 01, 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/why-john-mearsheimer-blames-the-us-for-the-crisis-in-ukraine.

[4] Glenn H. Snyder, “The Security Dilemma in Alliance Politics,” World Politics 36, no. 4 (1984): 461–495.

[5] Shawn Davies, Garoun Engström, Therese Pettersson, and Magnus Öberg, “Organized Violence 1989–2023, and the Prevalence of Organized Crime Groups,” Journal of Peace Research 61, no. 4 (2024).

[6] Hedley Bull, The Anarchical Society (London: Macmillan, 1977); Kenneth N. Waltz, “The Anarchic Structure of World Politics,” in: International Politics: Enduring Concepts and Contemporary Issues, 12th ed., ed. Robert Art and Robert Jervis (Boston: Pearson, 2011). And Helen Milner is interesting in: “The Assumption of Anarchy in International Relations Theory: A Critique,” Review of International Studies 17, no. 1 (1991): 67–85.

[7] For a cross-study of arguments for and against anarchy and the idea of ‘self-help’ see Charles L. Glaser, “Realists as optimists: Cooperation as self‐help,” Security Studies 5, no. 3 (1996): 122-163, and John Mearsheimer, “Anarchy and the Struggle for Power,” in: The Realism Reader, ed. Colin Elman and Michael Jensen (London: Routledge, 2014).ISBN 9780415773577.

[8] Gordon Graham, Ethics and International Relations, John Wiley & Sons, 2008. ISBN: 978-1-444-32692-5.

[9] The characteristics of states are often referred to as the Montevideo Convention, after the 1933 Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, which was held in the city of Montevideo, in Uruguay. It is a settled concept in international relations and international law. My current go-to textbook is Georg Sørensen, Jørgen Møller, and Robert Jackson, Introduction to International Relations: Theories and Approaches, 8th ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), see chapters 1 and 9. See also Thomas J. Biersteker, “State, Sovereignty, and Territory,” in: Handbook of International Relations, ed. Walter Carlsnaes, Beth A. Simmons, and Thomas Risse (London: SAGE, 2012).

[10] Robert Jervis, “Cooperation under the security dilemma,” World Politics 30, no. 2 (1978): 167-214. See also Charles L. Glaser, “The security dilemma revisited,” World Politics 50, no. 1 (1997): 171-201, and Shiping Tang, “The security dilemma: A conceptual analysis,” Security Studies 18, no. 3 (2009): 587-623.

[11] David A. Lake, Hierarchy in International Relations (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2011), https://doi.org/10.7591/9780801458934.

[12] Miles Kahler, “Agency, Power, and Governance,” in: Networked Politics: Agency, Power, and Governance, ed. Miles Kahler (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009), 1–20.https://doi.org/10.7591/9780801458880-003.

[13] Daniel H. Nexon and Thomas Wright, “What’s at stake in the American empire debate,” American Political Science Review 101, no. 2 (2007): 253-271.

[14] Mel Gurtov, “1. Crisis and Interdependence in Contemporary World Politics,” in: Global Politics in the Human Interest (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2007), 1–32.https://doi.org/10.1515/9781685857424-003.

[15] Daniel H. Nexon and Thomas Wright, “What’s at stake in the American empire debate,” American Political Science Review 101, no. 2 (2007): 253-271.

[16] Patrick J. McDonald, “Great Powers, Hierarchy, and Endogenous Regimes: Rethinking the Domestic Causes of Peace,” International Organization 69, no. 3 (2015): 557–88, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818315000120. See also Alastair Smith, “Alliance Formation and War,” International Studies Quarterly, Volume 39, no. 4 (1995):405–425. https://doi.org/10.2307/2600800.

[17] DSCA 2 (2022), “Policy Memorandum 22-38, Revision of the Program Execution Requirements,” Retrieved on January 11, 2024, https://samm.dsca.mil/policy-memoranda/dsca-22-38.

[18] Idem.

[19] Kevin Burkepile, Campaign Planning Handbook (Carlisle Barracks, PA: U.S. Army War College, 2023).

[20] Annual guidance.

[21] Philip Reynolds, “Security Conditionality: Evidence and Effectiveness,” Journal of Strategic Security 18, no. 1 (2025) : 89-116. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.18.1.2346.

[22] D. C. Treadway, W. A. Hochwarter, C. J. Kacmar, and G. R. Ferris, “Political Will, Political Skill, and Political Behavior,” Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior 26, no. 3 (2005): 229–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.310

[23] I. Kapoutsis, A. Papalexandris, D. C. Treadway & J. Bentley, “Measuring Political Will in Organizations: Theoretical Construct Development and Empirical Validation,” Journal of Management, 43, no. 7 (2015): 2252-2280. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314566460.

[24] E. Peterson and S. Iyengar, “Partisan Gaps in Political Information and Information-Seeking Behavior: Motivated Reasoning or Cheerleading?,” American Journal of Political Science, 65, no. 1 (2021):133–147, http://www.jstor.org/stable/45415617.

[25] Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political, trans. George Schwab (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), ISBN: 9780226738925.

[26] Philip Reynolds, “Security Conditionality: Evidence and Effectiveness,” Journal of Strategic Security 18, no. 1 (2025): 89-116. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.18.1.2346.

[27] Kristina Shampanier, Nina Mazar, and Dan Ariely, “Zero as a Special Price: The True Value of Free Products,” Marketing Science 26, no. 6 (2007): 742–57.