Abstract: Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine began in February 2022, YouTube has remained a primary platform for ordinary Russians to access uncensored information, in contrast to global news media banned by the Russian government. Analysing massive comments posted on YouTube is an imperative step to figuring out what Russian people are thinking about this war. However, Russian users’ discussions on YouTube have received sparse investigation in research on the Ukraine war.

Problem statement: How to visualise anonymous YouTube comments to figure out the topics discussed by individual Russian users regarding the Ukraine war?

So what?: For the first time, this study clearly shows that Russian users’ comments mentioning the Ukraine war indeed contain substantial discussion of international affairs. These findings better explain how Russian users react to the Ukraine war in social media discussions for social scientists who research public sentiments during the war.

YouTube – An Information Platform

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine began in February 2022, Russia has restricted domestic access to several major platforms, including news websites, Facebook, and Instagram. However, YouTube has avoided chiefly the Kremlin’s actions against American social media platforms. There has not been a counter-ban threatening to take YouTube offline. Since Russia invaded Ukraine, YouTube remains a primary platform for tens of millions of ordinary Russians to access uncensored information.

One reason for YouTube’s continued availability lies in its widespread popularity, which stands out from other social media. YouTube is Russia’s most favoured platform,[1] utilised by over 75% of the country’s internet users.[2] Some experts speculate that the Russian government might recognise YouTube as “too big to be blocked,” because restrictions in access to the most popular video platform is a significantly different matter compared to blocking other social media.[3] Western platforms banned in Russia receive less attention than YouTube,[4] since their user bases consist mostly of urban advanced intelligentsia[5] and are much smaller in size than YouTube viewers.[6]

YouTube is Russia’s most favoured platform, utilised by over 75% of the country’s internet users.

Another reason is the absence of comparable alternatives to YouTube in Russia.[7] Instead of Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, Russian users can migrate to V Kontakte or Yandex, popular online services provided by domestic companies.[8] In contrast, RuTube, a government-backed video platform, has not achieved the same level of popularity as YouTube due to its smaller audience and lack of available monetisation options.[9] Indeed, Digital Development Minister Maksut Shadayev explains that a ban on YouTube could only be considered when a competitive alternative exists, and the ministry has repeatedly stated that the issue of blocking YouTube is not currently on the agenda.[10]

YouTube itself also expresses its desire to operate in Russia to keep ordinary citizens informed about global perspectives and events regarding Ukraine, even though the company was fined by Roskomnadzor, Russia’s telecommunications regulator, for not removing forbidden content.[11] Indeed, YouTube remains one of the limited spaces where Russians can view and discuss images of the war from independent sources,[12] and services provided by YouTube are still available in Russia and Ukraine as one of the few tools for activists who organise and disseminate messages free from Russian government control.[13]

Of course, over the last decade, Russian authorities like Roskomnadzor have monitored YouTube videos that criticise the Russian government and the mood of comments in social media messages.[14] Nonetheless, YouTube comments are well-suited for discussing sensitive subjects like the war in Ukraine. Several factors contribute to YouTube’s current independent position in Russia. With commenters remaining anonymous, YouTube offers a relatively secure environment to minimise the risk of being detained for expressing one’s views. Furthermore, domestic platforms like VK are far more censored and surveilled by the Russian government than anything that the West is providing.[15]

With commenters remaining anonymous, YouTube offers a relatively secure environment to minimise the risk of being detained for expressing one’s views.

As such, in a YouTube environment enabling free speech online, individual users could offer a detailed picture of what is happening in Ukraine by accessing uncensored information from global news media.

On the flip side, some users hired by Russian authorities may possibly express pro-government opinions or political preferences aligned with the Putin administration, masquerading as ordinary citizens by abusing the anonymity-preserving comment section of YouTube. Such practice of posting provocative or offensive messages online for political purposes is termed political trolling.[16] Certain social media accounts linked to Russia’s professional trolls are reported to support Russian actions in Ukraine or advocate for President-elect Trump.[17]

Indeed, Russia’s most famous troll factory, known as “the Internet Research Agency,” is in St. Petersburg, and the company is financed by a close President Putin ally with ties to Russian intelligence.[18] Inside the facility, hundreds of employees post 135 comments per 12-hour shift in exchange for 40,000 rubles ($700) monthly, with the task of clogging the websites with pro-Kremlin narratives. Consequently, numerous comments on the Ukraine war increasingly originate from “the Internet Research Center.”[19]

In addition to the manual work of Russian propaganda, social media bots are emerging trends in information operations research driven by advancements in digital media technology. Bot accounts are used in attempts to influence users and change people’s perspectives,[20] in contrast to traditional propaganda that controls information flow.[21] This new type of propaganda strategy is called Cognitive Warfare, which focuses on altering how a target population thinks and how it acts through it.[22] Especially in recent years, the Russian government has actively targeted younger generations, who watch less traditional television, by using YouTube’s system because of the growing importance of online formats in extending the reach of its propaganda effort.[23]

Bot accounts are used in attempts to influence users and change people’s perspectives, in contrast to traditional propaganda that controls information flow.

These instances show the importance of YouTube, where public opinion and propaganda exist side by side, and anonymous discussions on the platform prove valuable for figuring out how Russians react to this war.

Data Collection

Video selections are made by searching for videos with two keywords, namely “украина (Ukraine)” and “война (war),” and filtering the results based on the highest view count as of April 2023. Popular YouTube videos related to the War in Ukraine, as shown in Table 1, focus on topics like how the war has impacted daily life for Ukrainian and Russian people.

Videos featuring influencers or intellectuals discussing everyday life make the top eleven ranking positions. Videos, ranking below twelfth place, cover topics concerning Russo-Ukrainian relations and current affairs. The trend in view counts suggests that Russian users show greater interest in reflections on daily life during the war rather than political matters. From the eleven most-viewed YouTube videos on the Ukraine war, a dataset comprising 313,148 comments has been generated in this study. Russian comments are collected using the Python module “requests.” This library simplifies gathering massive comments through the YouTube API and recording the comments alongside metadata such as “Likes.”

Regarding data collection ethics, the list of YouTube comments and the usernames are not shared in this study, in accordance with the assessment arguing detailed information, including usernames, should remain undisclosed unless necessary as ethical practices for the analysis of YouTube comments.[24]

The collected YouTube comments are then pre-processed, by using “spacyr,” which supports multiple languages and parses the parts of speech from each word. “spacyr” is a free, open-source library for lexical tokenization provided by the “quanteda” package, capable of handling non-Latin scripts like Japanese, Russian or Chinese.[25] “spacyr” breaks the comments into individual words and then combines different forms of the same word into a single word to match all forms of inflectional endings in Russian. For instance, “Россия (Russia),” “России (of Russia),” and “Россию (to Russia)” all become “Россия (Russia),” by processing slight changes at the end of a word with “spacyr.” Next, additional text cleaning is performed with “Marimo”,[26] covering non-European languages, to remove all “stop words.” “Stop words” are words that provide little analysis-relevant information, such as “в (in)” or “это (this).” The processing set yields a final dataset for quantitative text analysis from YouTube comments.

The collected YouTube comments are then pre-processed, by using “spacyr,” which supports multiple languages and parses the parts of speech from each word.

Methods

The primary challenge faced by researchers in text analysis is the volume of data. Even in moderately sized corpora, manually reading all the texts remains challenging.[27] In recent years, quantitative text analysis has become an increasingly popular approach to the discovery of meaningful insight from large collections of unstructured text data. In this study, Co-Occurrence Analysis (CNA) and Latent Semantic Scaling (LSS) are utilised to detect specific topics from YouTube comments, because these methods are employed in political science studies that examine the prevailing discourses on social media platforms.[28], [29]

Additionally, as formal hypotheses are not built to prevent ideological bias and to better represent a starting point indicated by the data,[30] there are no specific expectations regarding topic patterns observed in YouTube comments at the outset of this analysis. As such, at a later stage, the analysis result is formally tested to provide a discussion of the data. This data-driven approach allows researchers to “discover topics from the data, rather than assume them.”[31]

Co-Occurrence Network Analysis (CNA)

CNA is a technique for visualising topics by connecting words that appear simultaneously in a sentence with a line. This method has been employed to examine relationships among terms in a text as part of content analysis.[32] Co-occurrence refers to the chance frequency of a pair of terms appearing together in any context, indicating semantic similarity across a set of documents or expressions. Based on the computed value of co-occurrence, networks connecting pairs of terms are generated. CNA is particularly beneficial for analysing large text and big data when identifying the main themes and topics, such as in numerous social media posts.[33]

Based on the computed value of co-occurrence, networks connecting pairs of terms are generated.

Latent Semantic Scaling (LSS)

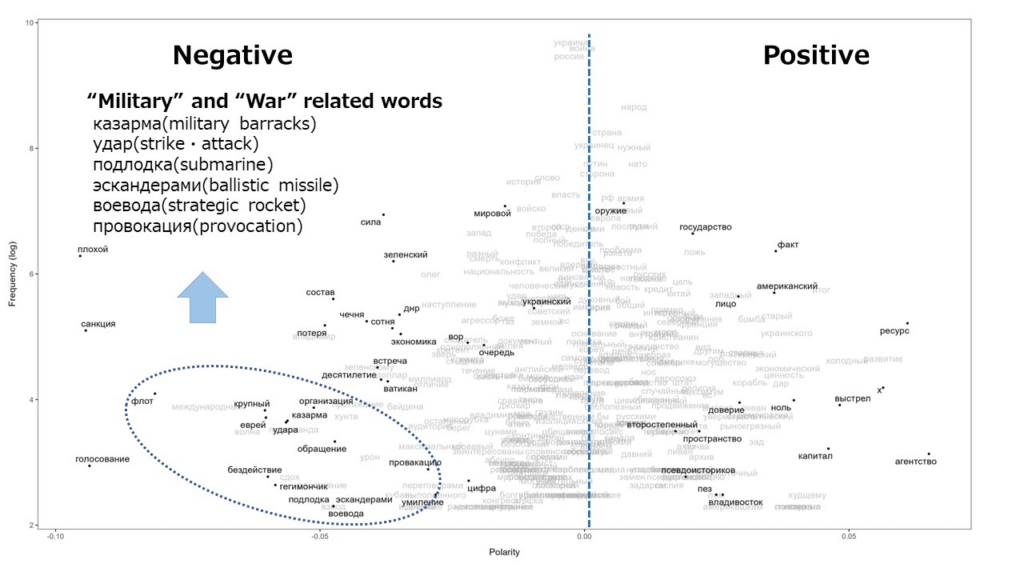

Latent Semantic Scaling (LSS), known as a semi-supervised machine learning model, employs word-embedding techniques to categorise words in the corpus into “negative” or “positive” classes. Classification with LSS relies on “seed words,” which are small sets of positive or negative words related to the topic or theme under consideration.[34]

The terms for “seed words” are defined by researchers based on their knowledge and understanding of a particular field. In using “seed words” for text classification based on their sentiment, polarity scores are assigned to each term in relation to “positive” and “negative.” For the LSS model, positive words receive a polarity score of +1, while negative words receive a polarity score of −1.[35]

Then, polarity scores for every word in the text corpus, excluding seed words, are computed to train machine learning models.[36] The LSS algorithm computes polarity scores depending on the relative proximity of words to positive and negative seed words.

It is still challenging for researchers to collect a substantial vocabulary related to the study’s focus on data computation. However, LSS enables the categorisation of text data with significantly less effort and facilitates the analysis of words in each topic from a specialist perspective, as the model only utilises a small set of words selected by the user in the study context.[37]

It is still challenging for researchers to collect a substantial vocabulary related to the study’s focus on data computation.

Results

Co-Occurrence Network Analysis (CNA)

As indicated below, “family,” “Christ” or “God” are to the right of the network map, while “USA,” “Kiev,” “West” or “China” are to the left. This result shows what topics Russian users are discussing, with abstract words concerning “human life and religion” on the left and “country and city names” more towards the right.

The left side of the network shows that topics regarding life or family are closely associated with religion.This could indicate that Russian users seemed to reaffirm the importance of their family and human life, by featuring Christian symbolism such as Christ, the Bible, or God in their comments. By contrast, the right side of the network consists of country and region names such as U.S., Kyiv, China, and these terms are more international and political. This means that Russian users mention some foreign countries at the same frequency as “human life and religion” “-related comments.

It is not surprising for discussions to be focused on religion or family when individuals are aware their lives could be in danger during the war. However, international relations topics in the War in Ukraine are worth further exploration, as “country and city names” alone are insufficient to draw valid conclusions related to an international topic.

Latent Semantic Scaling (LSS)

Before conducting LSS, the frequency of specific countries mentioned in YouTube comments is counted with the results shown in Table 2. References to the U.S., China, and NATO each exceed 1,000 occurrences in the overall corpus. China is the only country ranked in the top ten, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region. Russian users might recognise the top ten countries as stakeholders in the War in Ukraine. Interestingly, as presented in Table 3, West Asian countries are mentioned more frequently than Eastern European countries, which play a significant role in supporting Ukraine.

Since the importance of the U.S. in the War in Ukraine is well-demonstrated, as well as the well-publicised media coverage of China’s connections with Russia, comments that feature these two countries are analysed by LSS model. To estimate word-level polarity by LSS model, the list of seed words is created in Russian, as displayed in Table 4.

Considering data sets, LSS is specifically not run on the entire corpus but is conducted on two sub-selections of YouTube comments that reference China/Chinese people or U.S./American people, as shown in Figures 2 and 3, respectively.

In the U.S.-related comments, shown in Figure 2, words related to “Military and War,” such as “strike/attack,” “submarine,” and “ballistic missile,” are classified as negative with low polarity scores. In China-related comments, shown in Figure 3, words related to “Economy and Bilateral,” like “corporation,” “locomotive,” and “intimate,” are classified as positive with high polarity scores.

It is striking that military-related words stand out as prominent topics in comments regarding the U.S., while economy-related words appear to be more prominent in comments regarding China. However, it is important to note that both the U.S. and China are typically discussed as major stakeholders in Russia’s national security policy and economy. Therefore, military and economic topics are worth further exploration in two datasets of comments regarding the U.S. and China.

Tests

To evaluate the outcomes of the LSS model, the percentage of military and economic topics is calculated in two datasets of comments referencing the U.S. and China, based on the number of “Likes.” These metadata can be reasonably considered indicators of resonance and hot topics in social media discussions.[38] To calculate the topic percentages, distinct lists of words associated with military and economic topics are compiled, as shown in Tables 5 and 6. The lists include manually added keywords, clearly relevant to the two topics, along with words detected by the LSS model. Due to the broad range of values covered by “Likes,” a logarithmic scale is employed to simplify the comparison of metadata and topic percentages. As such, class intervals for “Likes” are placed as follows: 1-5, 5-10, 10-50, 50-100, 100-500.

This investigation defines topic percentages as a frequency distribution of military and economic themes in YouTube comments related to the U.S. or China. Consequently, the percentages of the two topics can be acquired by calculating how frequently comments containing words from Tables 5 and 6 appear within predefined intervals of “Likes.”

U.S. Comments

According to Table 7, there are noticeable differences in the volume of military and economic topics in U.S.-related comments: The percentage of military topics is 17.96%, and the percentage of economic topics is 10.49%.

As shown in the following chart, the military topic receives more “Likes” than the economic topic for most class intervals, except for 50-100. The military topic overwhelmingly leads the economic topic in U.S.-related comments.

China Comments

In Table 8, the volume of military and economic topics is roughly the same in overall comments related to China: The percentage of military topics is 13.07%, and the percentage of economic topics is 12.29%.

However, the economic topic stands out as a prominent subject in the 5-10 and 50-100 intervals. Particularly, as shown in Chart 2, the economic topic exceeds 33.3% in the 50-100 interval, with the corresponding decrease to 16.6% in the percentage of the military topic. When considering only the popular comments with the most “Likes,” the proportion of the economic topic is twice as high as that of the military topic in China-related comments.

Discussion

It is conceivable that there are distinctive trends in the discourse of the war in Ukraine shaped by Russian YouTube users. In YouTube comments, economic terms appear positively concerning China, while specific names of military weapons form a negative context for the U.S. Additionally, it is observed that discussions of economic cooperation receive much more “Likes” in China-related comments, while military terms dominate U.S.-related comments.

The analysed corpus provides evidence that Russian users are more inclined to express aggression against the U.S. by mentioning specific names of military weapons and a desire for economic and business cooperation with China under economic sanctions.

Indeed, China’s role as a function of Russia’s sanctions evasion is quite large and the Russian government’s continued hostility toward the U.S. demonstrates how substantial a threat American military assistance for Ukraine could pose. Given the reality in international relations, there may be an expectation for China’s role in the Russian economy and concerns about the American threat to Russia’s national security in Russian society beyond YouTube comments.

Of course, the approach suggested by this study also has several limitations, primarily due to the constraints faced by a sole researcher with limited resources. Firstly, with additional time and funding, it would be possible to aggregate a larger sample of YouTube comments related to specific countries in addition to the U.S. and China. Supplementary comment surveys of specific countries, presented in Table 2, could help discover new topics regarding stakeholders in the war, such as NATO, Poland, or Western European countries. Second, conducting more research on comments posted on other platforms is needed to suggest generalisable trends that might extend beyond YouTube, which could support or modify the conclusions presented in this study.

With additional time and funding, it would be possible to aggregate a larger sample of YouTube comments related to specific countries in addition to the U.S. and China.

Finally, geolocation analytics is also needed to find out who produces YouTube comments since the advent of social media platforms has increased the spread of propaganda on the part of various actors,[39] including domestic and foreign individual citizens and governments. Russian YouTube users may be “Russian-speaking users” from post-Soviet states or potentially be bots and state-sponsored accounts used for spreading Russian propaganda.

When looking at the corpus referencing China, the topic of economic cooperation is detected from the most frequently liked comments, which agrees with the assessment that “Russian propaganda spreads the promotion of pro-Beijing narrative as part of the fight against “American imperialism.”[40] Assuming that YouTube commenters are government cooperators or bots mimicking real people, Russian users are potentially being induced to support a specific political opinion through propaganda campaigns. The analysis result of China comments could be an exemplification of the view that “Cognitive warfare materialises the response to the supplied information.”[41]

However, this is merely a conjecture regarding the origin of YouTube comments without sufficient evidence. Russian propaganda tends to mirror what Russians think, even if it appears fundamentally unrealistic and absurd from a Western perspective,[42] which makes it difficult to draw a clear line between propaganda and personal opinions. In this study, for instance, although negative views of American military support receive much more “Likes,” the resulting analysis might show Russian individuals’ traditional feelings and behaviour, rather than the effectiveness of propaganda influence. Indeed, anti-Americanism has long been more prevalent among Russian citizens, with distrust toward the U.S. persisting since the Soviet era.[43]

Although negative views of American military support receive much more “Likes,” the resulting analysis might show Russian individuals’ traditional feelings and behaviour, rather than the effectiveness of propaganda influence. Indeed, anti-Americanism has long been more prevalent among Russian citizens, with distrust toward the U.S. persisting since the Soviet era.

As such, additional evidence is needed to judge whether Russian propaganda stokes these negative feelings. To identify who posts a particular comment, a rigorous analysis of the geolocation of mobile devices or computer terminals to the country, city, and regional level is crucially needed. Future research could involve collecting and examining IP address data available to detect specific users operating as members of Russian propaganda groups on social media.

More importantly, YouTube has been focusing on efforts that prevent the Russian government from exploiting its platforms for propaganda and disinformation.[44]

Conclusion

Setting aside inherent methodological limitations, several conclusions present themselves from examining YouTube comments related to the War in Ukraine. For the first time, it has become clear that Russian users’ comments mentioning the Ukraine war indeed contain substantial discussion of international affairs, in contrast to talking about day-to-day affairs during the war. Within this international discourse, the U.S.-related comments revolve heavily around the military topic, while China-related comments centre around the economic topic.

These findings better explain how Russian users react to the Ukraine war in social media discussions and open up new research questions for social scientists who research public sentiments during the war. Moreover, as metadata attached to YouTube comments enable the visualisation and quantification of user responses, this study approach of popularity metrics such as “Likes” could also provide further research opportunities into how the war in Ukraine influences individual and group behaviours online.

As metadata attached to YouTube comments enable the visualisation and quantification of user responses, this study approach of popularity metrics such as “Likes” could also provide further research opportunities into how the war in Ukraine influences individual and group behaviours online.

Apart from these conclusions regarding the war in Ukraine, this study suggests the potential of language processing dictionaries and machine learning algorithms for correctly capturing contexts to those interested simply in employing text mining techniques to minimise ideological bias in future research.

This study was supported by the Japan Science and Technology Agency [Grant Number JPMJSP2124, Program Name JST- SPRING]. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Akira Sano; Text mining, Russian study; University of Tsukuba, Japan Science and Technology Agency. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of any affiliation.

[1] J. Sherman “Why YouTube Has Survived Russia’s Social Media Crackdown—So Far,” by Perrigo B, TIME, (March 2022), https://time.com/6156927/youtube-russia-ukraine-disinformation/.

[2] eMarketer, “Why YouTube Has Survived Russia’s Social Media Crackdown—So Far,” by Perrigo B, TIME, (March 2022), https://time.com/6156927/youtube-russia-ukraine-disinformation/.

[3] J. Sherman “Why YouTube Has Survived Russia’s Social Media Crackdown—So Far,” by Perrigo B, TIME, (March 2022), https://time.com/6156927/youtube-russia-ukraine-disinformation/.

[4] E. Kabanov, “Russia Is Trying to Copy China’s Approach to Internet Censorship,” by E. Parker, SLATE, (April 2017), https://slate.com/technology/2017/04/russia-is-trying-to-copy-chinas-internet-censors hip.html.

[5] A. Soldatov, “Russia Is Trying to Copy China’s Approach to Internet Censorship,” by E. Parker, SLATE, (April 2017), https://slate.com/technology/2017/04/russia-is-trying-to-copy-chinas-internet-censors hip.html.

[6] E. Parker, “Russia Is Trying to Copy China’s Approach to Internet Censorship,” SLATE, (April 2017), https://slate.com/technology/2017/04/russia-is-trying-to-copy-chinas-internet-censors hip.html.

[7] A. Polyakova, “Google and Russia’s delicate dance,” by Iyengar R, CNN Business, (June 2022), https://edition.cnn.com/2022/06/03/tech/google-russia-youtube/index.html.

[8] R. Iyengar, “Google and Russia’s delicate dance,” CNN Business, (June 2022), https://edition.cnn.com/2022/06/03/tech/google-russia-youtube/index.html.

[9] E. Brooking, “Why Russia just can’t quit YouTube -Russia promotes domestic platform RuTube over YouTube as part of its vision for a parallel internet-,” by Adams K, Fernandez S, MARKETPLACE, (May 2022), https://www.marketplace.org/shows/marketplace-tech/why-russia-just-cant-quit-youtube/.

[10] M. Shadayev, “No plans to block YouTube in Russia – digital development minister,” Interfax, (May 2022), https://interfax.com/newsroom/top-stories/79198/.

[11] S. Wojcicki, “How YouTube Keeps Broadcasting Inside Russia’s Digital Iron Curtain,” by Schechner S, Kruppa N, Gershkovich E, The Wall Street Journal, (August 2022), https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-youtube-keeps-broadcasting-inside-russias-digital-iron-curtain-11659951003.

[12] S. Schechner, N. Kruppa, E. Gershkovich, “How YouTube Keeps Broadcasting Inside Russia’s Digital Iron Curtain”, The Wall Street Journal, (August 2022), https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-youtube-keeps-broadcasting-inside-russias-digital-iron-curtain-11659951003.

[13] K. Harbath, “Tech’s crackdown on Russian propaganda is a geopolitical high-wire act”, by Bond S, National Public Radio, (March 2022), https://www.npr.org/2022/03/01/1083824030/techs-crackdown-on-russian-propaganda-is-a-geopolitical-high-wire-act.

[14] P. Mozur, A. Satariano, A. Krolik, A. Aufrichtig, “They Are Watching’: Inside Russia’s Vast Surveillance State,” The New York Times, (September 2022).

[15] J. Sherman “Why YouTube Has Survived Russia’s Social Media Crackdown—So Far,” by Perrigo B, TIME, (March 2022), https://time.com/6156927/youtube-russia-ukraine-disinformation/.

[16] P. Fichman, McClelland, “The impact of gender and political affiliation on trolling,” First Monday, 26-1 (2020), https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/11061/10034.

[17] Office of the Director of National Intelligence, “Assessing Russian Activities and Intentions in Recent Elections,” INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY ASSESSMENTS, (2017), https://www.intelligence.senate.gov/sites/default/files/publications/ICA_2017_01.pdf.

[18] Idem.

[19] M. Burkhard, “One Professional Russian Troll Tells All,” by Volchek D, Sindelar D, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, (March 2015), https://www.rferl.org/a/how-to-guide-russian-trolling-trolls/26919999.html.

[20] S. Woolley, D. Guilbeault, “Computational Propaganda in the United States of America: Manufacturing Consensus Online,” Computational Propaganda Reserch Project, Working Paper No.5 (2017): 1-29.

[21] J. Giordano, “The brain is the battlefield of the future,” by Gajjar D, THE GEOSTRATA, (April 2023), https://www.thegeostrata.com/post/cognitive-warfare.

[22] O. Backes, A. Swab, “Cognitive Warfare: The Russian Threat to Election Integrity in the Baltic States,” Policy analysis exercise, (2019): 48.

[23] M. Wijermars, “Google and Russia’s delicate dance,” CNN Business, (June 2022), https://edition.cnn.com/2022/06/03/tech/google-russia-youtube/index.html.

[24] P. Reilly, “The ‘Battle of Stokes Croft’ on YouTube: The development of an ethical stance for the study of online comments,” Sage Research Methods, Cases Part 1 (2014).

[25] K. Benoit, K. Watanabe, H. Wang, P. Nulty, A. Obeng, S. Müller, A. Matsuo, “quanteda: An R package for the quantitative analysis of textual data,” Journal of Open Source Software, 3-30 (2018): 774.

[26] K. Watanabe, “Latent Semantic Scaling: A Semisupervised Text Analysis Technique for New Domains and Languages,” Communication Methods and Measures, 15-2 (2021): 81-102.

[27] J. Grimmer, BM Stewart, “Text as Data: The Promise and Pitfalls of Automatic Content Analysis Methods for Political Texts,” Political Analysis, 21-3 (2013): 267-297.

[28] E. Segev, “Textual network analysis: Detecting prevailing themes and biases in international news and social media,” Sociology Compass, 14-4 (2020): e12779.

[29] N. Umansky, “Who gets a say in this? Speaking security on social media,” New Media & Society, 0-0 (2022), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/14614448221111009.

[30] D. Miller, “Characterizing QAnon: Analysis of YouTube comments presents new conclusions about a popular conservative conspiracy,” First Monday, 26-2 (2021).

[31] M. E. Roberts, B. M. Stewart, D. Tingley, C. Lucas, J. Leder-Luis, S. K. Gadarian, B. Albertson, D. G. Rand, “Structural Topic Models for Open-Ended Survey Response,” American Journal of Political Science, 58-4 (2014): 1064-1082.

[32] H. Chen, X. Chen, H. Liu, “How does language change as a lexical network? An investigation based on written Chinese word co-occurrence networks,” PloS one 13, no.2 (2018): 1-22.

[33] E. Segev, “Textual network analysis: Detecting prevailing themes and biases in international news and social media,” Sociology Compass, 14-4 (2020): e12779.

[34] K. Watanabe, “Latent Semantic Scaling: A Semisupervised Text Analysis Technique for New Domains and Languages,” Communication Methods and Measures, 15-2 (2021): 81-102.

[35] Idem.

[36] Idem.

[37] Idem.

[38] D. Miller, “Characterizing QAnon: Analysis of YouTube comments presents new conclusions about a popular conservative conspiracy,” First Monday, 26-2 (2021).

[39] D. Cocking, J. van den Hoven, Evil Online (Hoboken, New Jersey: Blackwell, 2018).

[40] Centre for Strategic Communication and Information Security, “Twitter, YouTube and Rubbish Websites. How Russia Promotes Its Propaganda in the West after Blocking of TV Channels,” SPLAVDI, (September 2022), https://spravdi.gov.ua/en/twitter-youtube-and-rubbish-websites-how-russia-promotes-its-propaganda-in-the-west-after-blocking-of-tv-channels/.

[41] J. Giordano, “The brain is the battlefield of the future,” by Gajjar D, THE GEOSTRATA, (April 2023), https://www.thegeostrata.com/post/cognitive-warfare.

[42] E. Fedchenko, “Under the skin—Russian propaganda on the territory of Ukraine,” by Biernat J, Swietlik W, (August 2023), https://fake-hunter.pap.pl/en/node/94.

[43] D. Volkov , “Why Is Anti-Americanism in Russia Less Widespread Now Than in 2014?,” Russia Matters, (October 2022), https://www.russiamatters.org/analysis/why-anti-americanism-russia-less-widespread-now-2014.

[44] K. Harbath, “Tech’s crackdown on Russian propaganda is a geopolitical high-wire act”, by Bond S, National Public Radio, (March 2022), https://www.npr.org/2022/03/01/1083824030/techs-crackdown-on-russian-propaganda-is-a-geopolitical-high-wire-act.