Abstract: The People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) rapid rise in global cyber warfare threatens economic stability and geopolitical security. Their state-backed cyber espionage, targeting governments, corporations, and institutions, raises concerns about intellectual property theft and political espionage. Allegations of targeting critical infrastructure add to the potential for significant economic harm. The integration of cyber warfare into the PRC’s People’s Liberation Army doctrine demonstrates their ambition to be a dominant digital force, focusing on offence and defence. In response, the global community has increased concerns, adopted countermeasures, and engaged in diplomatic efforts. The PRC’s cyber strategy, tied to state-sponsored hacking, military investments, and economic interests, presents complex challenges. International cooperation, transparency, and establishing cyber norms are crucial in addressing these issues. The PRC’s impact on global cyber warfare underscores the need for vigilance and diplomacy.

Problem statement: How does power relate to curiosity, creative thinking, destruction, and other factors within international relations and digital combat?

So what?: It is crucial for nations, organisations and individuals to prioritise cyber protection amidst an increased reliance on cyberspace technologies. Nations should strengthen their defences, share threat intelligence, and impose sanctions against nations that employ such capabilities. Governments must work together to establish multilateral treaties, international norms and (pressing and innovative) rules for cyberspace governance, ensuring a secure cyberspace for the human future.

Source: shutterstock.com/Frame Stock Footage

Genius or Moron

Michel Foucault finds ‘Power’ to be not only of a political nature but essentially inherent in all our manifestations, no matter how trivial they are.[1] On the other hand, Nietzsche found that underlying interests are at the core of all human social actions.[2] Here, the historically apparent differences between Power and Interests are the equivalent entangled relations in their most vivid form and simultaneous consciousness.[3]

Historical context reveals that geniuses and morons share a fragile connection. Intelligence can camouflage itself behind a veneer of simplicity; a genuine creative mastermind lies within.[4] Crossing the mental threshold where clarity ceases to exist leaves room for speculation regarding one’s true nature.[5] Humans have a long history of hubris or inordinate pride. We frequently feel that we are wiser and more powerful than we are. This arrogance may lead to rash actions, in this context, utilising cyberspace in ways damaging ourselves and others.[6] Cyberspace allows us to connect with the world and distribute information. However, this power can be tempting to abuse when utilised against one’s enemy, especially if one feels justified.[7] It may be used to influence and control people and cause malicious disruption to public life and infrastructure, nearing fatal outcomes. This can also be abused to disseminate disinformation and propaganda. We lack awareness about cyberspace’s full potential and how it might cause more damage than good. This is because we may be underestimating the threats it brings. We may not realise the perils of this unknown power and turn on the user with the same harm that the one is attempting to inflict on the other. The arrogance of being a brilliant creator of this virtual power may be a dangerous source of destruction even for the bearer.[8] Here the creative genius turns into a moron and a cause of destruction.

Humans have a long history of hubris or inordinate pride. We frequently feel that we are wiser and more powerful than we are.

Global trade perilously balances at the precipice of disaster owing to tariff squabbles and purported pandemic plots.[9] Powerful states are occupying strategic positions within key regions.[10] Thanks to no-fly zones and missile defence systems, trade paths are being carefully observed. States are lost in disillusionment as they ignore the mounting crises.[11] This gloomy landscape comprises weapons proliferation, stalled climate action, commercial tensions, military aggrandisement, and politicking.[12] One careless individual having access to innovative technologies puts our entire planet at risk, much like a countdown to disaster.[13]

China and Cyberspionage

Modern-day digital opponents show remarkable strategic prowess, persistence, and determination when striving to gain total command over systems and networks.[14] Full-throttle operations involve every nation-state mobilising its hacking force. In situations, information plays a crucial role and is available in great quantities through social media platforms, which are well-informed about everyone everywhere; meanwhile, massive amounts of data are transferred internationally daily thanks to big data, machine learning, and artificial intelligence techniques. The balancing act of governance hangs the tenuous fate of humanity in the balance. On a planetwide scale, individuals displaying varying degrees of intelligence confront one another, utilising digital innovations to subvert existing power structures, challenge deeply ingrained beliefs, and jeopardise the security of vital data that flows, gets analysed, or remains within cyber frameworks.[15] Nations possess greater resources, target options, and motivations for cyberattacks than individuals. This includes financial, human, and technological resources, a broader range of potential targets, and political, military, or economic motivations.[16]

Individuals displaying varying degrees of intelligence confront one another, utilising digital innovations to subvert existing power structures, challenge deeply ingrained beliefs, and jeopardise the security of vital data.

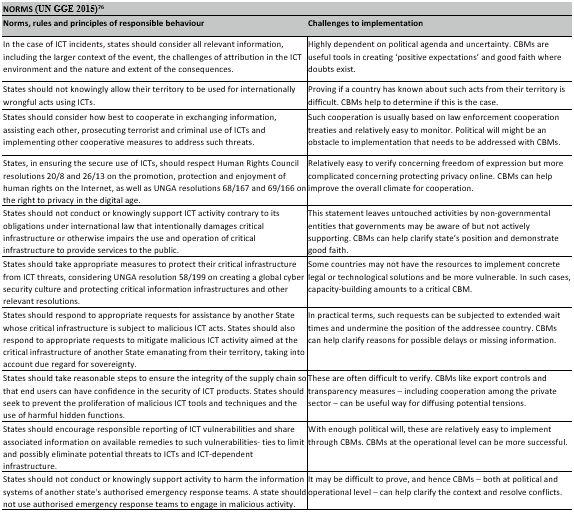

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has earned a reputation among cyberespionage experts for being an incredibly prolific actor. The People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) Cyber Force hacked into numerous government, military, and corporate computer systems, resulting in the theft of classified data.[17] Per the Mandiant report, the Advanced Persistent Threat (APT41)[18] represents a massive cyberattack orchestrated by the PRC’s government through their cyber command, i.e. PLA Unit 61398, which targeted 141 companies across various industries over several years of persistent intrusion.[19], [20]

![Hierarchical structure of the PRC’s hacking apparatus, pointing out Unit 61398.[21]](https://tdhj.org/media/0d3ede_1fd9cc20a3294233b982465a674d7de8~mv2.png)

Hierarchical structure of the PRC’s hacking apparatus, pointing out Unit 61398.[21]

Reportedly relying on Snowden’s exposés, sources including The Guardian, Época, The Huffington Post, Der Spiegel, and The New York Times documented numerous instances of suspicious behaviour perpetrated by the Unit 61398 hacking into U.S. Covid relief benefits and stealing $20 million and hacking into United Nations (UN) International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNIDR) computers located in several countries globally.[22] That was their next stop after breaching data centres and securing servers in major tech corporations.[23] According to The Guardian, a profiling technique called “understudy of habits,” will devour massive amounts of information gathered by the NSA.[24]

Cyber Warfare – A Full-Scale War

A report from C4ISRNET reveals that the European Defence Agency engaged in ‘live fire’ exercises involving 17 member states assaulting virtual servers during real-time cyber range training with actual goals.[25] Expansion has shifted the battlefield dynamics, resulting in cyber warfare becoming an additional full-scale fight. Every day, the CRINK nations (China, Russia, Iran and North Korea) backed -attacks that threatened the U.S. Cyber Command; however, APT groups receiving state financing offer defence.[26] This is similar to the complex dance of causing distress while avoiding irreparable repercussions and the subsequent compliance resulting from it with resources and expenses incurred by the enemy; this strategy played by the communist block back in the USSR days balanced an equation like this: Impact vs. Implications and Results vs. Restrictions.[27] Where ‘Impact’ is the immediate or direct effect and ‘Implications’ are the possible or likely consequences. In this context, the impact of a cyberattack on a financial institution could be the loss of money, which could be recovered. However, the implications of a cyberattack on a government financial institution could be a loss of trust, economic damage, or even social unrest, which is far more detrimental. Along similar lines, ‘Result’ is the outcome or consequence against the ‘Restrictions,’ i.e. the limitations imposed on the realisation of the result. In this context, a cyberattack on a government financial institution Results in economic and social disruption, and in response to that, the restrictions and regulations imposed by the government on financial institutions and their operations and due diligence mechanism increase the cost of operations and operational strain.

Under certain circumstances, such as those encountered during a retaliatory predicament or comparable scenarios, cyber warfare has been exploited by today’s adversaries as an element of their overall battle plan. Following the January 01, 2016, DDoS (distributed denial-of-service) attacks on U.S. Banks incident involving Iran.[28] The ‘Defend Forward’ policy prompted a proactive defence response from the Department of Defence (DoD).[29] Economic security is under serious attack, as evidenced by the current menace that has invaded our financial infrastructure, comprised of stock markets, trading funds, and even the basic framework of capitalism.[30] Peaceful periods enable subtle operations that involve Intellectual Property (IP) and private information robbery through cunning methods.[31] Another way to undermine society is through misleading reports and manipulation of facts regarding political reforms or elections.

Cyber warfare has been exploited by today’s adversaries as an element of their overall battle plan.

With its PLA Cyber Force, the PRC ranks high among states engaging in cyberattacks that can be construed as acts of cyber warfare. Hackers have innovated highly effective tools like advanced persistent threats (APT), zero-day exploits, and huge DDoS strikes, enabling illicit access to computers and overpowering their defences.[32] Armstrong attributes the destruction of vital assets and infrastructure to recent attacks.[33]

According to Speier, conflict extends beyond commercial activities; currency and institutional interests face instability.[34] The Sony Pictures Entertainment incident 2011, reported in The New York Times in 2014 whilst covering similar attacks on Sony targeting the release of the movie ‘Fury’, showcases this scenario. The attack was believed to be in retaliation for the release of the film “The Interview”, which was a comedy about an assassination plot against North Korean leader Kim Jong-un.[35] The attacks targeted at price fluctuations of stocks and commodities, DDoS assaults are attributed towards the PRC by the U.S. government.

The capital market ecosystem is indispensable and susceptible within the purview of the nation’s essential infrastructure (EI), meaning that cybersecurity risks threaten its capacity to support financial systems across nations. Breaching the last defence translates into reaching that point within cyberspace,[36] considered the pinnacle of accomplishment by adversaries. Alongside economic espionage charges, the PRC faces allegations of disrupting important systems via online assaults. As reported by The Washington Post, the PLA Cyber Force was responsible for a significant cyber assault on Google’s password system in 2010 using Taiwanese IP.[37] These attacks were among the initial in the series with government and corporate espionage intent.[38]

The capital market ecosystem is indispensable and susceptible within the purview of the nation’s essential infrastructure.

Weaponised weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) and cyber warfare may be seen in the same category of damage and may cause widespread destruction, interrupting critical infrastructure and creating economic and societal loss. WMDs may create significantly greater devastation, killing or hurting a large number of people and creating long-term environmental harm. They can be employed to achieve political, military, or economic goals such as acquiring critical information, disrupting enemy activities, or gaining a competitive edge. As technology progresses, governments and non-state actors will find it simpler and less expensive to build and deploy these cyber weapons, raising the prospect of catastrophic cyber warfare or WMD-like attacks. The use of these weapons raises ethical and moral considerations since they can result in civilian losses and the spread of these weapons to other governments or non-state actors.

Adoption Of and Adapting To the Cyber Norms

The emergence of international norms against cyber warfare is a positive development, but it is important to note that these norms are not legally binding and can be broken. Therefore, states need to commit to upholding these norms and take steps to implement them.

A norm is a standard of behaviour commonly recognised and followed by a group of individuals. Norms can be formal or informal and can be enforced in several ways, including social pressure, legal consequences, or economic benefits. Norms are essential in international law.[39] They can assist in filling legal gaps and assist in interpreting and implementing current legislation. Norms can also serve to foster inter-state cooperation and dispute resolution. One method norms aid in formulating a new path of international law in the UN is by serving as a starting point for negotiations.[40] Governments frequently refer to current norms for guidance when negotiating a new treaty or resolution. This is because standards may serve as a foundation for nations to develop upon. Another way that standards aid in formulating a new path of international law is by creating pressure for change. When a standard becomes generally recognised, nations may feel pressured to comply, even if it is not legally compulsory. This is because states may fear the implications of being viewed as non-compliant with a generally established standard.[41] Finally, norms can assist in implementing and enforcing new international legislation. Norms can also assist in identifying and filling legal loopholes. Norms have aided in formulating a new course of international law in the UN.[42]

Governments frequently refer to current norms for guidance when negotiating a new treaty or resolution.

International standards emerge and are agreed upon at the UN through consensus-building and negotiation.[43] This procedure can be difficult and time-consuming, but ensuring that international rules are broadly recognised and applied is necessary.[44] The first stage in developing an international standard is identifying a need. Governments, non-governmental organisations, or other players can do this.[45] When a need is found, a norm entrepreneur usually emerges to advocate the new norm. Individuals or groups that seek to encourage the acceptance of new norms are referred to as norm entrepreneurs. The norm entrepreneur will then start gaining support for the new norm. This may be accomplished through various means, including study, advocacy, and lobbying. The norm entrepreneur will also try to foster agreement on the new norm. This entails reaching a consensus among all key stakeholders on the new norm’s definition, content, and extent. Once there is general agreement on the new standard, it may be established in various ways.[46] This might include the UN General Assembly passing a resolution if a two-thirds majority is met among the members, signing a treaty, or developing a non-binding code of conduct. It is critical to encourage the application of the new standard after it has been codified. The UN plays an important role in establishing and disseminating international rules. It offers a place for states to meet and develop new rules and gives technical support and training to nations to assist in implementing international rules.[47]

A few examples to refer to from the past on how international norms have developed and been agreed upon in the UN include the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in 1948,[48] the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) in 1989, and the Paris Agreement on climate change in 2015. The UDHR is a non-binding declaration that has significantly impacted international law and human rights worldwide.[49] The CRC is a legally binding treaty that outlines children’s rights and has been widely ratified, improving the lives of millions. The Paris Agreement, adopted in 2015,[50] aimed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and limit global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, having been ratified by over 190 countries.[51] These agreements represent significant steps in the fight against climate change.

Cyberacts are at the early stages of norm development. Emergent norms are new standards that are still being established and accepted. They are frequently distinguished by a lack of clarity and unanimity on their definition, meaning, and extent.[52] There are several reasons why cyberacts are classified as emerging norms.[53] First and foremost, cyberacts are a relatively recent phenomena. The Internet has become widely available, and cyber technologies have expanded significantly in that period. As a result, we still do not know much about cyberacts and their possible implications. Cyberacts are multinational.[54] They may be carried out from anywhere globally and have a worldwide influence. This makes developing and implementing international conventions to govern cyberacts challenging.

Cyberacts are at the early stages of norm development. Emergent norms are new standards that are still being established and accepted.

Furthermore, there is no agreement on how to describe and classify cyberacts.[55] Cybercrime, for example, is already addressed by current laws and regulations. Other cyberacts, such as cyberespionage and cyber warfare, on the other hand, are more challenging to define and govern.[56] However, there are currently no systems in place to enforce cyber rules. Even if governments agree on cyber rules, ensuring states follow those norms might be problematic.[57] This is because cyberacts can be committed anonymously and from anywhere globally. Despite these obstacles, there is growing agreement that cyber rules are required. States are increasingly realising the importance of working together to solve the issues posed by cyberacts. This collaboration creates new cyber standards, such as those governing responsible state activity in cyberspace. The evolution of cyber standards is a continuous process.[58] As we learn more about cyberacts and the usage of cyber technology expands, cyber standards are likely to change further.

Establishing Cyberlaw and Consensus

There have been several reasons why the UN has struggled to establish cyberlaw and failed to find consensus on several critical topics. One reason is that cybersecurity is a complicated and ever-evolving domain. It might be difficult for nations to agree on responding to new and emerging cybersecurity threats.[59] Another reason is that cybersecurity is such a delicate subject. States are hesitant to relinquish control over their cybersecurity and adhere to international standards. This is particularly true for governments with significant cyber capabilities. Finally, there is a lack of trust between states. States do not trust one another to follow international cybersecurity standards. This is due to the widespread perception of cybersecurity as a zero-sum game in which one state’s gain is another state’s loss.[60]

Several times, the UN has struggled and failed to implement cyberacts. For example, in 2013, the UN General Assembly (UNGA) passed a resolution to create a comprehensive international cybersecurity treaty. Member nations, however, have been unable to agree on the content of such a convention. In 2015, the UNGA passed a resolution establishing a Group of Governmental Experts on Information Security (GGEIS).[61] The GGEIS was entrusted with generating suggestions for improving international cybersecurity cooperation and defining principles for responsible state activity in cyberspace.[62] The GGEIS, however, could not agree on several critical topics, including the concept of cyber warfare and the standards of responsible state activity in cyberspace.[63] The UN General Assembly formed an Open-ended Working Group (OEWG) on digital security in 2019. The OEWG has been assigned to generate recommendations for addressing cybersecurity concerns comprehensively and holistically.[64] However, due to differences among member nations, the OEWG has been unable to make considerable headway.[65] Despite these obstacles, the UN continues to work on cyberacts. The UNGA has formed various working groups and expert groups to investigate cybersecurity challenges and make suggestions on how to handle them. The UN has also played a role in setting a framework, gathering consensus on the norms, fostering international cybersecurity cooperation and defining principles of responsible state behaviour in cyberspace.[66] However, the UN will continue to struggle to pass cyberlaw and establish agreement on several critical concerns. This is due to cybersecurity’s complexity, the issue’s sensitivity, and the lack of trust among governments.

Setting Binding and Non-Binding Instruments

The prospect of a globally enforceable binding multilateral agreement on cyberacts with unanimous support is remote. Before such an agreement can be achieved, several obstacles must be overcome. The intricacy of cybersecurity is the most significant of multiple challenges. Cybersecurity is a quickly growing subject, and keeping up with the latest threats and technology may be challenging. As a result, governments find it difficult to agree on the elements that should be included in a binding agreement, not only in cyber norms but also in other matters.[67] Another issue is cybersecurity’s sensitivity. Cybersecurity is a subject of national security, and governments are hesitant to relinquish authority over cybersecurity to conform to international norms.[68] This is particularly true for governments with robust cyber capabilities. There is also a lack of trust among states. States do not trust one another to follow a legally binding agreement against cybercrime.[69] This is because cybersecurity is frequently viewed as a strictly competitive scenario or a simple reference to understanding the Nash Equilibrium,[70] which defines an action profile for all state participants in a strategy and is used to anticipate the result of their decision-making interaction.[71] Because of the various uncertainties in the global geopolitical arena, no player can benefit by unilaterally changing its policy, i.e. one state’s gain is another state’s loss.

The intricacy of cybersecurity is the most significant of multiple challenges. Cybersecurity is a quickly growing subject, and keeping up with the latest threats and technology may be challenging.

States that might have been interested in entering into norm entrepreneurship may back out due to a lack of previous support and current non-conducive terms. For example, in 1999, Russia proposed a set of “principles of international information security” to the UN Secretary-General, creating the OEWG, but received little support.[72] Hence, in 2004, the UN established a Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) to develop norms of responsible state behaviour in cyberspace.[73] In 2013, the GGE process resulted in the approval of a consensus report articulating the core standards for cyberspace governance. Russia’s goals in establishing the OEWG are to review current cyber standards and make new commitments that suit its interests. Russia thought the OEWG should be more inclusive and have the authority to amend or rewrite current cyber agreements and standards.

In 2013, the Global Governance Initiative (GGE) issued a consensus report articulating fundamental cyber principles, reinforcing international law, state sovereignty, and human rights. The 2015 report expanded on the concept of nonintervention in the internal affairs of other nations and stressed governments’ obligation to preserve essential infrastructure. These developments affected later conversations about cyber norms, particularly those at the OEWG.[74] Due to differences concerning governments’ rights to respond to unjust acts using ICTs and the applicability of international humanitarian law in cyberspace, the 2017 UN GGE failed to establish a consensus. As a result, there is widespread disappointment and pessimism about the future development of cyber norms.[75] Six Global Governance Groups (GGEs) have been formed, including the 2019-2021 GGE, which Russia and its allies reject. Despite the absence of unanimity, the 73rd session of the UNGA First Committee effectively relaunched the process of negotiating cyber norms. This is an example of ‘Two Steps forward – One step backward’ momentum of the UN’s cyber norms consensus progression.

Despite the UN’s many hurdles, several circumstances might lead to developing a globally enforceable multilateral agreement on cyberacts. One factor is the world’s growing interconnection. States are increasingly vulnerable to cyber assaults as they become more reliant on digital technology. This creates a common motive for governments to collaborate on cybersecurity and adopt norms and standards to regulate cyberspace.[77] Another aspect is the rising realisation that cyberattacks might seriously affect global peace and security. Cyberattacks on a major infrastructure might disrupt the global economy or lead to violence.[78] This increases the pressure on nations to take action to address the issue of growing cyber threats.

Cyberattacks can have a substantial direct and indirect impact on people. Direct consequences include the inability to access key services, the loss of personal data, and bodily injury. For example, in 2017, a ransomware assault on a hospital in Denmark necessitated cancelling elective procedures and redirecting patients to other institutions.[79] Cyberattacks can also result in the theft of personal data, which can lead to financial loss, identity theft, and other problems. Target Corporation, for example, had a ‘Kill Chain’ data breach in 2013 that exposed the personal information of nearly 70 million consumers.[80] Cyberattacks can inflict physical harm in some situations, as evidenced in the 2010 Stuxnet worm assault on Iran’s nuclear program, which damaged centrifuges used to enrich uranium.[81] Cyberattacks can inflict economic harm, loss of trust, and concern in the long run. They interrupt companies, resulting in employment losses, as shown in the 2017 WannaCry ransomware assault.[82] They also diminish public faith in institutions, making them harder to operate successfully. For example, the 2016 breach of the Democratic National Committee’s email server resulted in a loss of faith in the Democratic Party and the U.S. government.[83] Cyberattacks may also instil dread and anxiety in people, particularly those who have been directly impacted by them, such as those who have lost personal data or have been victims of ransomware attacks.

In 2017, a ransomware assault on a hospital in Denmark necessitated cancelling elective procedures and redirecting patients to other institutions.

For numerous reasons, cyberattacks on critical infrastructure might be deemed a danger to a state’s essential interests. Cyberattacks can damage key infrastructure such as electricity grids, transportation networks,[84] and financial markets.[85] This disruption can considerably impact a state’s economic, national security, and public safety. Cyberattacks can potentially steal sensitive data such as national security secrets, intellectual property, and personal information. This type of information theft may harm a country’s reputation, hurt its economy, and jeopardise national security. Cyberattacks can be used to carry out attacks on other countries. A cyberattack, for example, may be used to cripple a state’s air defence, leaving it open to a traditional military strike.[86] The Sony Picture cyberattack mentioned earlier is the best example of the hacker group Guardians of Peace. The hackers stole a large amount of data from Sony, including personal information about employees and unreleased films.[87] The attack was widely seen as a cyberattack that was intended to intimidate and silence Sony and was used by the North Koreans, causing a threat to the freedom of expression. Article 2(4) of the UN Charter[88] requires that states refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state or in any other manner inconsistent with the purposes of the UN. This also applies in cyberspace.

Article 51 of the UN Charter recognises states’ right to self-defence against an armed attack. This right can also be understood to apply to cyberattacks against critical infrastructure, as such attacks could be considered a threat to a state’s vital interests. Also, Article 55 of the Charter[89] calls for international cooperation to maintain peace and security. This cooperation can include cooperation on cybersecurity and the protection of critical infrastructure. In addition to the UN Charter, several other international instruments address the protection of civilians from cyberattacks. For example, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC)[90] has stated that international humanitarian law (IHL) applies to cyber operations during armed conflict. IHL prohibits targeting civilians and civilian objects, and it requires parties to an armed conflict to take all feasible precautions to minimise the civilian impact of their operations.

Article 51 of the UN Charter recognises states’ right to self-defence against an armed attack. This right can also be understood to apply to cyberattacks against critical infrastructure.

The Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols (GCIAP)[91] are the foundational international Humanitarian Law treaties (IHL).[92] The GCIAP prohibits the targeting of civilians, civilian objects, and objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population. The GCIAP could be adapted to protect the protected[93] entities in consideration of cyber warfare.

The Convention on Cybercrime (Budapest Convention) is a treaty that aims to criminalise cybercrime and to promote international cooperation in combating cybercrime.[94] The Budapest Convention contains several provisions that are relevant to the protection of civilians from cyberattacks, such as provisions on offences against the confidentiality, integrity and availability of computer data and systems (Article 2 on Illegal Access),[95] offences relating to computer systems (Article 3), and offences related to content (Article 4 on Data interference).[96] For example, Article 2 of the Budapest Convention criminalises unauthorised access to a computer system, which could be used to launch a cyberattack against civilians.

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Global Cybersecurity Agenda (GCA): The GCA is a non-binding framework that sets out some principles and recommendations for improving cybersecurity. The GCA contains provisions relevant to protecting civilians from cyberattacks, such as the principle that “cybersecurity is essential for the protection of human rights”[97] and the recommendation that “States should take steps to protect their critical infrastructure from cyberattacks”.[98]

The UN Convention Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW)[99] prohibits or restricts the use of certain conventional weapons considered to be excessively injurious or have indiscriminate effects. Protocol I on Non-Detectable Fragments[100] could be interpreted to prohibit cyber weapons that cause permanent or long-term damage to human tissue, such as cyber weapons that target the nervous or immune systems. For instance, consider the possibility of malware that interferes with the operation of medical equipment, such as pacemakers and insulin pumps, which can endanger individuals who rely on them for survival.[101]

The UN Convention Certain Conventional Weapons prohibits or restricts the use of certain conventional weapons considered to be excessively injurious or have indiscriminate effects.

Protocol II on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps and Other Devices could be understood to prohibit cyber-triggered mines[102] and booby-traps.[103], [104] This is mentioned in the Ottawa Convention.[105] For example, suppose a kill switch embedded in a piece of malware planted by cyber means into the target computer system operates unexpectedly when a user performs a normally safe task, such as turning on the computer. In that case, the cyber device may fall under the Protocol II definition of a booby-trap or mine.[106]

Protocol III on Incendiary Weapons[107] could be interpreted to prohibit cyber weapons that cause widespread and long-term fires, such as cyber weapons that target power grids or communication networks.[108] Cyberattacks on power grids can cause widespread power outages, leading to several health risks, including hypothermia, carbon monoxide poisoning, and respiratory problems.

Protocol IV on Blinding Laser Weapons[109] could be interpreted to prohibit cyber weapons that cause permanent blindness, such as computer-operated weapons that target the human retina. Precision-guided ammunition is intended to hit a specific target precisely to minimise collateral damage. This technology delivers high-frequency millimetre-wavelength electromagnetic rays that heat the tissue on contact.[110]

While certain international laws may apply, the lingering vagueness around cyber warfare exposes people and organisations to risk. Article 5 of NATO’s original founding treaty,[111] intended to protect member nations’ freedom, established the trigger for a collective reaction as “an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America.” NATO Article 5 protection may be applied against a cyberattack.[112]

Article 5 of NATO’s original founding treaty, intended to protect member nations’ freedom.

There is a growing body of international law and norms on cybersecurity.[113] This includes the UN Framework Convention for Cyber Law,[114] the Budapest Convention on Cybercrimes,[115] the Tallinn Manual 2.0,[116], [117] and the Paris Call for Trust and Cooperation in Cyberspace.[118] These instruments provide a foundation for developing a binding agreement on cyberacts. Overall, the likelihood of a globally binding multilateral agreement on cyberacts is uncertain. Several challenges need to be addressed before such an agreement can be reached. However, the world’s increasing interconnectedness, the growing recognition of the impact of cyberattacks, and the growing body of international law and norms on cybersecurity suggest that such an agreement is possible. In 2015, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution that called for developing norms of responsible state behaviour in cyberspace. This resolution recognised the potential dangers of cyber warfare, called for states to take steps to prevent its use, and proposed confidence-building measures (CBMs).[119]

Grey areas in international treaties and conventions may be exploited for cyber warfare, disrupting global peace.[120] States may launch cyberattacks without fear of reprisal, increasing cyber warfare and decreasing global security. The complexity of international law and differing interpretations make it difficult to maintain clear rules and norms for new technologies like cyber weapons.[121] States may also be unwilling to enforce international law, fearing it would harm their interests and deter them from launching cyberattacks.[122] Therefore, addressing these issues is crucial for global security.

The misuse of grey areas in international treaties for cyber warfare could lead to increased cyberattacks, decreased global security, and undermine international law.[123] To address this issue, states should collaborate to develop new international norms and standards for responsible cyber weapon use, implement international law more effectively, strengthen domestic legislation, improve international cooperation, and enhance cybercrime investigation and prosecution capacity.[124] Additionally, states should be willing to hold each other accountable for cyberattacks through diplomatic channels, sanctions, or military action.[125] Addressing the problem of grey areas in international treaties being abused for cyber warfare is a complex challenge.[126] However, it is important to take action to address this problem in order to protect the global order.

Power and Responsibility

In Spider-Man Comics, Uncle Ben said, “With great power comes great responsibility.”[127] To counteract these risks, experts cite Admiral Arleigh Burke’s advice to employ a multi-point defence system against breaches at various vulnerable entry points, such as those targeted during “Operation Cloud Hopper.”

A threat arises when 5G functionality is hosted virtually on the cloud, per Network Security Journal.[128] According to SBA experts, segment topology obstruction allows discreet data access control.[129] With an emphasis on digital realms, we now turn to cyberspace for social bonding, material well-being, and day-to-day operations. According to the Harvard Journal of Cybersecurity,[130] our personal information is now available through the Internet of Things (IoT).

According to a 2022 survey by the UN Institute for Disarmament Research,[131] 61% of experts believe a globally binding multilateral agreement on cyberacts will likely be achieved in the next 10-20 years. However, the survey also found a significant risk of conflict in cyberspace in the next 5-10 years if states do not address cyber threats. Clearly, the international community needs to do more to address cyber threats and develop norms and rules to govern cyberspace. A globally binding multilateral agreement on cyberacts would be a significant step in this direction.

According to a 2022 survey by the UN Institute for Disarmament Research, 61% of experts believe a globally binding multilateral agreement on cyberacts will likely be achieved in the next 10-20 years.

Several countries, such as India, the U.S., and Australia, restrict Huawei and ZTE under national security directives; however, not every nation does so, which presents an issue because of the possibility of spying or damage. Hackers must identify vulnerabilities located elsewhere; this is all required to compromise security systems.[132]

War destroys cultural treasures, financial institutions, population health, ecological balance, and societal organisation.[133] While advancements are made to better our lifestyle, an increasing number of techniques have the potential to go awry within society. Lens-wise, both factors mesh into ‘the people, by the people, for the people’.[134] Technology usage decides between positive evolution (Genius) and disastrous collapse (Moronic)!

The Need for An International Cyberwar Convention

The world needs an international cyberwar convention with norms that define possibilities of human, economic and infrastructural harm via cyber intervention. Nation states should keep their differences aside and envision cyberweapons as deadly as nuclear weapons and treat them like a weapon of mass destruction, given their capability, reach and potential magnitude. There needs to be a comprehensive ‘Cyberwar Banning Treaty’ inclusive of the norms of non-development of cyber-capabilities for causation of mass destruction. The UN must declare the classification of cyber warfare as deadly as WMDs. This might have far-reaching consequences. It would raise awareness among governments about the need for increased cybersecurity expenditure and the development of new international standards, rules, collaborative measures, and conventions. It would also make it more difficult for governments to utilise cyber warfare, causing them to be more careful before employing such weapons. This might dissuade cyberattacks and lower the likelihood of violent war. Furthermore, it would strengthen the UN’s mandate to combat cyber warfare, allowing it to adopt additional penalties and measures to dissuade governments from employing such weapons.

As cyber weapons become more sophisticated and accessible, a growing consensus is that multilateral agreements must ban them. Cyber weapons are indiscriminate and have the potential to wreak broad destruction to create economic and social loss and threats to human life. They are getting more complex and simple to create, making it simpler for non-state actors such as terrorist groups and criminal organisations to obtain cyber weapons.

As cyber weapons become more sophisticated and accessible, a growing consensus is that multilateral agreements must ban them.

Cyber warfare has the potential to blur the distinction between war and peace, leading to heightened tensions and armed confrontations. Because there is no international agreement on the use of cyber weapons, holding governments accountable for their activities in cyberspace is challenging. While prohibiting mass intrusion programs and codes is a difficult and time-consuming operation, it is one that governments must do to avoid cyber warfare.

To prevent mass intrusion programs and codes, countries should collaborate to develop international norms and laws, establish clear guidelines for other cyber weapons, and invest in cybersecurity measures.

Prohibiting cyber weapons would protect national infrastructure from damage, enhance cyberspace stability, and encourage state cooperation from compliant nations, also assisting the swing nations in cooperating. These steps would also prevent the spread of these programs to other governments and non-state actors, making the world safer and potentially stopping the development and sale of these programs by rogue nations and terrorist organisations.

Vipul Tamhane is an Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing (AML/CFT) specialist and advises corporations, governments, and law enforcement agencies on legal and compliance issues. Vipul is a visiting faculty at the Department of Defence and Strategic Studies at Pune University. He provides AML/CFT training and advice to law enforcement and government entities. He is the Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Diplomacy Direct, an India-based public interest Think Tank (and YouTube Channel), and writes about counter-terrorism and geopolitics. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone.

[1] Robert Young, “Michael Foucault, The Order of Discourse, Untying the Text: A Post Structuralist Reader,” Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981, 57-74.

[2] Brian Leiter, “Nietzsche’s Moral and Political Philosophy,” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Summer 2021 Edition.

[3] K. Smith, “The Stealth of Genius: Unveiling the Hidden Knowledge,” Journal of Intellectual Exploration 15 (4): 423-440.

[4] Idem.

[5] H. Akın Ünver, “Politics of Digital Surveillance, National Security and Privacy,” Centre for Economics and Foreign Policy Studies, 2018.

[6] Erik Gartzke, “The Myth of Cyberwar: Bringing War in Cyberspace Back Down to Earth,” International Security 38, no. 2 (2013): 41–73.

[7] Sarah Buss, “Justified Wrongdoing,” Noûs 31, no. 3 (1997): 337–369.

[8] Liah Greenfeld and Daniel Chirot, “Nationalism and Aggression,” Theory and Society 23, no. 1 (1994): 79–130.

[9] S. Ghosh, “COVID-19, Clean Energy Stock Market, Interest Rate, Oil Prices, Volatility Index, Geopolitical Risk Nexus: Evidence from Quantile Regression,” Journal of Economics and Development 24, no. 4 (2022): 329-344.

[10] Peter Jay, “Regionalism as Geopolitics,” Foreign Affairs 58, no. 3 (1979): 485-514.

[11] Mark Haugaard, “Foucault and Power: A Critique and Retheorization,” Critical Review 34, no. 3-4 (2022): 341-371.

[12] C. Reynolds, “Global Health Security and Weapons of Mass Destruction Chapter,” In Global Health Security, 187-207.

[13] Kalle Lyytinen and Gregory M. Rose, “The Disruptive Nature of Information Technology Innovations: The Case of Internet Computing in Systems Development Organizations,” MIS Quarterly 27, no. 4 (2003): 557-596.

[14] S. Ghosh, “COVID-19, Clean Energy Stock Market, Interest Rate, Oil Prices, Volatility Index, Geopolitical Risk Nexus: Evidence from Quantile Regression,” Journal of Economics and Development 24, no. 4 (2022): 329-344.

[15] Aakansha Natani “Contending Perspectives On Digital Democracy,” World Affairs: The Journal of International Issues 25, no. 1 (2021): 10–23.

[16] RA. Atrews, “Cyberwarfare: Threats, Security, Attacks, and Impact,” Journal of Information Warfare 19, no. 4 (2020): 17–28.

[17] Desmond Ball, “China’s Cyber Warfare Capabilities,” Security Challenges 7, no. 2 (2011): 81-103.

[18] Mandiant, “APT1: Exposing One of China’s Cyber Espionage Units,” https://www.mandiant.com/resources/reports/apt1-exposing-one-chinas-cyber-espionage-units.

[19] Z. Li, “What we know about the Chinese army’s alleged cyber spying unit,” https://edition.cnn.com/2014/05/20/world/asia/china-unit-61398/index.html.

[20] Magnus Hjortdal, “China’s Use of Cyber Warfare: Espionage Meets Strategic Deterrence,” Journal of Strategic Security 4, no. 2 (2011): 1-24.

[21] Mandiant, “APT1: Exposing one of China’s cyber espionage units,” Mandiant, https://www.mandiant.com/resources/reports/apt1-exposing-one-chinas-cyber-espionage-units.

[22] The New York Times, “Cyber Attack on Sony,” https://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/31/business/media/sony-attack-first-a-nuisance-swiftly-grew-into-a-firestorm-.html.

[23] K. Zetter, “Chinese military group linked to hacks of more than 100 companies,” Wired, https://www.wired.com/2013/02/chinese-army-linked-to-hacks/.

[24] The Guardian, “NSA Surveillance and Whistleblowing,” https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jun/09/edward-snowden-nsa-whistleblower-surveillance.

[25] Sebastian Sprenger, “Live-fire drill puts Europe’s military cyber responders to the test,” C4ISRNET, https://www.c4isrnet.com/global/europe/2021/02/19/live-fire-drill-puts-europes-military-cyber-responders-to-the-test/.

[26] Mandiant, “APT1: Exposing one of China’s cyber espionage units,” Mandiant, https://www.fireeye.com/content/dam/fireeye-www/services/pdfs/mandiant-apt1-report.pdf.

[27] James P. Farwell, “Industry’s Vital Role in National Cyber Security,” Strategic Studies Quarterly 6, no. 4 (2012): 10-41.

[28] Jan-Philipp Brauchle et al., “Cyber Risks to Financial Stability,” In: Cyber Mapping the Financial System, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2020, 10-13.

[29] Alan Mears and Joe Mariani, “The Temporal Dimension of Defending Forward: A UK Perspective on How to Organize and Innovate to Achieve US Cyber Command’s New Vision,” The Cyber Defense Review 5, no. 1 (2020): 55–74.

[30] Solly Zuckerman, “Judgment and Control in Modern Warfare,” Foreign Affairs 40, no. 2 (1962): 196-212.

[31] J. Lynch, “Identity Theft in Cyberspace: Crime Control Methods and Their Effectiveness in Combating Phishing Attacks,” Berkeley Technology Law Journal.

[32] Khalid Walid Mahmoud, “Cyber Attacks: The Electronic Battlefield. Arab Center for Research & Policy Studies,” 2013.

[33] H. L. Armstrong, “Denial of Service and Protection of Critical Infrastructure,” Journal of Information Warfare 1, no. 2 (2001): 23–34.

[34] Hans Speier, “The Effect of War on the Social Order,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 218 (1941): 87-96.

[35] B. Barnesand N. Perlroth, “Sony Pictures and F.B.I. Widen hack inquiry,” The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/04/business/sony-pictures-and-fbi-investigating-attack-by-hackers.html.

[36] G. E. Noel and M. G. Reith, “Cyber Warfare Evolution and Role in Modern Conflict,” Journal of Information Warfare 20, no. 4 (Fall 2021): 30-44.

[37] Ariana Eunjung Cha and Ellen Nakashima, “Google China cyberattack part of vast espionage campaign, experts say,” The Washington Post, January 14, 2010.

[38] Ellen Nakashima, “Chinese Hackers Who Breached Google Gained Access to Sensitive Data, U.S. Officials Say,” Washington Post, May 18, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/chinese-hackers-who-breached-google-gained-access-to-sensitive-data-us-officials-say/2013/05/20/51330428-be34-11e2-89c9-3be8095fe767_story.html.

[39] Richard H. McAdams, “The Origin, Development, and Regulation of Norms,” Michigan Law Review 96, no. 2 (1997): 338–433.

[40] Oscar Schachter, “United Nations Law,” The American Journal of International Law 88, no. 1 (1994): 1–23.

[41] Harold Hongju Koh, “Review of Why Do Nations Obey International Law?,” by Abram Chayes, Antonia Handler Chayes, and Thomas M. Franck, The Yale Law Journal 106, no. 8 (1997): 2599–2659.

[42] Robert T. Coulter, “THE LAW OF SELF-DETERMINATION AND THE UNITED NATIONS DECLARATION ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES,” UCLA Journal of International Law and Foreign Affairs 15, no. 1 (2010): 1–27.

[43] Barry Buzan, “Negotiating by Consensus: Developments in Technique at the United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea,” The American Journal of International Law 75, no. 2 (1981): 324–48.

[44] Palitha T. B. Kohona, “The International Rule of Law and the Role of the United Nations,” The International Lawyer 36, no. 4 (2002): 1131–44.

[45] Wolfgang Friedmann, “The United Nations and the Development of International Law,” International Journal 25, no. 2 (1970): 272–86.

[46] Martha Finnemore and Kathryn Sikkink, “International Norm Dynamics and Political Change,” International Organization 52, no. 4 (1998): 887–917.

[47] Ramesh Thakur and Thomas G. Weiss, “United Nations ‘Policy’: An Argument with Three Illustrations,” International Studies Perspectives 10, no. 1 (2009): 18–35.

[48] John P. Humphrey, “The Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” International Journal 4, no. 4 (1949): 351–61.

[49] Herzel H. E. Plaine, “ORIGINS OF THE UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS,” Negro History Bulletin 14, no. 2 (1950): 27–33.

[50] Jessica Durney, “Defining the Paris Agreement: A Study of Executive Power and Political Commitments,” Carbon & Climate Law Review 11, no. 3 (2017): 234–42.

[51] Ralphe Bodle, Lena Donat, and Matthias Duwe, “The Paris Agreement: Analysis, Assessment and Outlook,” Carbon & Climate Law Review 10, no. 1 (2016): 5–22.

[52] Jeffrey L. Caton, “DISTINGUISHING ACTS OF WAR IN CYBERSPACE: ASSESSMENT CRITERIA, POLICY CONSIDERATIONS, AND RESPONSE IMPLICATIONS,” Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, 2014.

[53] Milton Mueller, Karl Grindal, Brenden Kuerbis, and Farzaneh Badiei, “Cyber Attribution: Can a New Institution Achieve Transnational Credibility?,” The Cyber Defense Review 4, no. 1 (2019): 107–22.

[54] Elena Chernenko, Oleg Demidov, and Fyodor Lukyanov, “Increasing International Cooperation in Cybersecurity and Adapting Cyber Norms,” Council on Foreign Relations, 2018.

[55] Erica D. Borghard and Shawn W. Lonergan, “Confidence Building Measures for the Cyber Domain,” Strategic Studies Quarterly 12, no. 3 (2018): 10–49.

[56] John B. Sheldon, “Cyberwar,” Encyclopedia Britannica, September 20, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/cyberwar, accessed November 07, 2023.

[57] United Nations, “Cyberconflicts and National Security | United Nations,” https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/cyberconflicts-and-national-security.

[58] United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), Report of the Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security, UNGAOR, 68th Sess, UN Doc A/68/98*(2013) (2013 GGE Report) (later adopted by the UNGA Resolution A/RES/68/243 ); UNGA, Report of the Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security, UNGAOR, 70th Sess, UN Doc A/70/174 (2015) (2015 GGE Report) (later adopted by the UNGA Resolution A/RES/70/237 ); UNGA, Report of the Open-ended working group on developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security, UN Doc A/75/816 (2021) (2021 OEWG Report); UNGA, Report of the Group of Governmental Experts on Advancing Responsible State Behaviour in Cyberspace in the Context of International Security, 76th Sess, UN Doc A/76/135 (2021) (2021 GGE Report) (both later adopted by UNGA Resolution A/RES/76/19).

[59] Anupam Basu, Ika Poetranto, and Joe Lau, “The UN Struggles to Make Progress on Securing Cyberspace,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, May 19, 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/05/19/un-struggles-to-make-progress-on-securing-cyberspace-pub-84491.

[60] Brian M. Mazanec, “Why International Order in Cyberspace Is Not Inevitable,” Strategic Studies Quarterly 9, no. 2 (2015): 78–98.

[61] Group of governmental experts – UNODA. (n.d.), https://disarmament.unoda.org/group-of-governmental-experts/.

[62] Heli Tiirmaa-Klaar, “The Evolution of the UN Group of Governmental Experts on Cyber Issues,” https://hcss.nl/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Klaar.pdf.

[63] Anders Henriksen, “The End of the Road for the UN GGE Process: The Future Regulation of Cyberspace,” Journal of Cybersecurity 5, no. 1 (2019): 9.

[64] K. Smith, “The Stealth of Genius: Unveiling the Hidden Knowledge,” Journal of Intellectual Exploration 15 (4): 423-440.

[65] Sheetal Kumar, “The OEWG’s consensus report: key takeaways,” Global Partners Digital. (n.d.), https://www.gp-digital.org/the-oewgs-consensus-report-key-takeaways/.

[66] B. Hogeveen, “The UN norms of responsible state behaviour in cyberspace,” https://documents.unoda.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-UN-norms-of-responsible-state-behaviour-in-cyberspace.pdf.

[67] Katerina Linos and Tom Pegram, “The Language of Compromise in International Agreements,” International Organization 70, no. 3 (2016): 587–621.

[68] Martin C. Libicki, “Norms and Normalization,” The Cyber Defense Review 5, no. 1 (2020): 41–54.

[69] Roger Hurwitz, “Depleted Trust in the Cyber Commons,” Strategic Studies Quarterly 6, no. 3 (2012): 20–45.

[70] Robert Aumann and Adam Brandenburger, “Epistemic Conditions for Nash Equilibrium,” Econometrica 63, no. 5 (1995): 1161–80.

[71] Mathias Risse, “What Is Rational about Nash Equilibria?,” Synthese 124, no. 3 (2000): 361–84.

[72] Poetranto, A. Basu, I. & J. Lau, “The UN struggles to make progress on securing cyberspace,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/05/19/un-struggles-to-make-progress-on-securing-cyberspace-pub-84491.

[73] Group of governmental experts – UNODA. (n.d.), https://disarmament.unoda.org/group-of-governmental-experts/.

[74] CCDCOE. (n.d.), https://ccdcoe.org/incyder-articles/a-surprising-turn-of-events-un-creates-two-working-groups-on-cyberspace/.

[75] Christian Ruhl, Duncan Hollis, Wyatt Hoffman, and Tim Maurer, “The UN GGE,” Cyberspace and Geopolitics: Assessing Global Cybersecurity Norm Processes at a Crossroads, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2020.

[76] (UN GGE 2015 Report), CCDCOE. (n.d.-b), https://ccdcoe.org/incyder-articles/2015-un-gge-report-major-players-recommending-norms-of-behaviour-highlighting-aspects-of-international-law/.

[77] Alastair MacGibbon, “Cyber Security: Threats and Responses in the Information Age,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 2009.

[78] Ryan C. Maness and Brandon Valeriano, “The Impact of Cyber Conflict on International Interactions,” Armed Forces & Society 42, no. 2 (2016): 301–23.

[79] Cyberattacks in responses to the Quran burning, both in terms of the media-coverage given to the incident by Russian media and the potentially paid-for “activist” responses. Danish hospitals hit by cyberattack from ‘Anonymous Sudan.’ (n.d.), https://therecord.media/danish-hospitals-hit-by-cyberattack-from-anonymous-sudan.

[80] Today, K. M. U. T. U. (2017, May 23), Target to pay $18.5M for 2013 data breach that affected 41 million consumers. USA TODAY, https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2017/05/23/target-pay-185m-2013-data-breach-affected-consumers/102063932/.

[81] K. Zetter, “An unprecedented look at Stuxnet, the world’s first digital weapon,” Wired, https://www.wired.com/2014/11/countdown-to-zero-day-stuxnet/.

[82] https://www.kaspersky.co.in/resource-center/threats/ransomware-wannacry.

[83] K. Fazzini, “How the Russians broke into the Democrats’ email, and how it could have been avoided,” CNBC, https://www.cnbc.com/2018/07/16/how-russians-broke-into-democrats-email-mueller.html.

[84] Transportation system cyberattacks can result in accidents, injuries, and even fatalities. In 2015, for example, a cyberattack on the Ukrainian power grid caused severe blackouts, disrupting the country’s transportation infrastructure. This resulted in a series of mishaps, including a train derailment that killed 32 people. K. Zetter, “Inside the cunning, unprecedented hack of Ukraine’s power grid,” Wired, https://www.wired.com/2016/03/inside-cunning-unprecedented-hack-ukraines-power-grid/.

[85] ThomasKrause, Rolf Ernst, Bernd Klaer, Ingmar Hacker, and Martin Henze, “Cybersecurity in Power Grids: Challenges and Opportunities,” Sensors (Basel) 21, no. 18 (2021): 6225. doi: 10.3390/s21186225. PMID: 34577432; PMCID: PMC8473297.

[86] J. M. Acton, “Cyber Weapons and Precision-Guided Munitions – Understanding Cyber Conflict: 14 Analogies,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, https://carnegieendowment.org/2017/10/16/cyber-weapons-and-precision-guided-munitions-pub-73397.

[87] Idem.

[88] Matthew C. Waxman, “Cyber Attacks as ‘Force’ Under UN Charter Article 2(4),” International Law Studies 87 (2011): 43.

[89] Bernhard Schlüter, “The Domestic Status of the Human Rights Clauses of the United Nations Charter,” California Law Review 61, no. 1 (1973): 110–64.

[90] International Committee of the Red Cross, “Cyber Operations during Armed Conflicts,” last accessed October 31, 2022, https://www.icrc.org/en/war-and-law/conduct-hostilities/cyber-warfare.

[91] Joseph Guay and Lisa Rudnick, “What the Digital Geneva Convention means for the future of humanitarian action,” UNHCR Innovation, The Policy Lab, June 25, 2017, last accessed October 31, 2022, https://www.unhcr.org/innovation/digital-geneva-convention-mean-future-humanitarian-action/.

[92] Eitan Diamond, “Applying International Humanitarian Law to Cyber Warfare,” Edited by Pnina Sharvit Baruch and Anat Kurz, Law and National Security: Selected Issues, Institute for National Security Studies, 2014.

[93] Idem.

[94] Amalie M. Weber, “The Council of Europe’s Convention on Cybercrime,” Berkeley Technology Law Journal 18, no. 1 (2003): 425–46.

[95] Idem.

[96] Idem.

[97] https://www.g20.org/content/dam/gtwenty/gtwenty_new/document/august_docs/ADOPTED_HLPS_ON_PROMOTING_INTEGRITY.pdf.

[98] Gary Waters, “The Case for a Regional Cyber Security Action Task Force,” Security Challenges 7, no. 1 (2011): 1–10.

[99] “The Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons,” UNODA. (n.d.), https://disarmament.unoda.org/the-convention-on-certain-conventional-weapons/.

[100] J. Ashley Roach and Michael J. Matheson, “Current Action on the Conventional Weapons Convention of 1980,” proceedings of the Annual Meeting (American Society of International Law) 90 (1996): 381–84.

[101] P. Jaret, “Exposing vulnerabilities: How hackers could target your medical devices,” AAMC, https://www.aamc.org/news/exposing-vulnerabilities-how-hackers-could-target-your-medical-devices.

[102] “‘Mine’ means a munition placed on, under or near the ground or other surface area and designed to be exploded by the presence, proximity or contact of a person or vehicle,” Amended Protocol on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Mines, Booby-Traps and Other Devices art. 2(1), May 03, 1996, 2048 U.N.T.S. 93 [hereinafter CCW Amended Protocol II].

[103] “‘Booby-trap’ means any device or material which is designed, constructed or adapted to kill or injure and which functions unexpectedly, when a person disturbs or approaches an apparently harmless object or performs an apparently safe act.” Id., art. 2(4).

[104] J. McClelland, “Conventional Weapons: A Cluster of Developments,” The International and Comparative Law Quarterly 54, no. 3 (2005): 755–567.

[105] Ibid., art. 2 (defines anti-personnel mines as meaning mines “designed to be explod-ed” by specified events).

[106] TALLINN MANUAL, supra note 9, rule 44.

[107] Lukas Andriukaitis, Emma Beals, Graham Brookie, Eliot Higgins, Faysal Itani, Ben Nimmo, Michael Sheldon, Elizabeth Tsurkov, and Nick Waters, “Incendiary Weapons,” Breaking Ghouta, Atlantic Council, 2018.

[108] R. A. Atrews, “Cyberwarfare: Threats, Security, Attacks, and Impact,” Journal of Information Warfare 19, no. 4 (2020): 17–28.

[109] Burrus M. Carnahan and Marjorie Robertson, “The Protocol on ‘Blinding Laser Weapons’: A New Direction for International Humanitarian Law,” The American Journal of International Law 90, no. 3 (1996): 484–490.

[110] Physicians for Human Rights and INCLO, “Lethal in Disguise: The Health Consequences of Crowd-Control Weapons,” (March, 2016).

[111] B. Lete and P. Chase, “Shaping Responsible State Behavior in Cyberspace,” https://nato-engages.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Shaping-Responsible-State-Behavior-in-Cyberspace.pdf.

[112] S. Waugh, “Geneva Conventions for Cyber Warriors Long Overdue,” www.nationaldefensemagazine.org.

[113] D. Hollis, “A brief primer on international law and cyberspace,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/06/14/brief-primer-on-international-law-and-cyberspace-pub-84763.

[114] I. Wilkinson, “What is the UN cybercrime treaty and why does it matter?,” Chatham House – International Affairs Think Tank, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2023/08/what-un-cybercrime-treaty-and-why-does-it-matter.

[115] “Budapest Convention,” Cybercrime, www.coe.int (n.d.), Cybercrime, https://www.coe.int/en/web/cybercrime/the-budapest-convention.

[116] The NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (NATO CCD COE) has been addressing the subject of ‘cyber norms’ since its establishment in 2008. The Centre has focussed on the question of how existing international legal norms apply to cyberspace. Tallinn Manual on the International Law Applicable to Cyber 8 International Cyber Norms: Legal, Policy & Industry Perspectives Warfare (2013).

[117] The Tallinn Manual. (n.d.), https://ccdcoe.org/research/tallinn-manual/.

[118] “Paris Call for trust and security in cyberspace,” Paris Call. (n.d.), https://pariscall.international/en/.

[119] Report of the UN GGE 2015 (later adopted by the UN General Assembly Resolution A/RES/70/237), which includes: Principles of State sovereignty, the settlement of disputes by peaceful means, and non-intervention in the internal affairs of other states apply to cyberspace. 2015 UN GGE – Report of the group of governmental experts on developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security (A/70/174) | Digital Watch Observatory. (n.d.). Digital Watch Observatory. https://dig.watch/resource/un-gge-report-2015-a70174.

[120] Gary Brown and Keira Poellet, “The Customary International Law of Cyberspace,” Strategic Studies Quarterly 6, no. 3 (2012): 126–145.

[121] Brian M. Mazanec, “Why International Order in Cyberspace Is Not Inevitable,” Strategic Studies Quarterly 9, no. 2 (2015): 78–98.

[122] Noah Simmons, “A Brave New World: Applying International Law of War to Cyber-Attacks,” Journal of Law & Cyber Warfare 4, no. 1 (2014): 42–108.

[123] David Wallace and Mark Visger, “Responding to the Call for a Digital Geneva Convention: An Open Letter to Brad Smith and the Technology Community,” Journal of Law & Cyber Warfare 6, no. 2 (2018): 3–55.

[124] Theresa Hitchens and Nilsu Goren, “International Cybersecurity Information Sharing Agreements,” Center for International & Security Studies, U. Maryland, 2017.

[125] Michael Gervais, “Cyber Attacks and the Laws of War,” Journal of Law & Cyber Warfare 1, no. 1 (2012): 8–98.

[126] Russell Buchan, “Cyber Attacks: Unlawful Uses of Force or Prohibited Interventions?,” Journal of Conflict and Security Law 17, no. 2 (2012): 211–27.

[127] Spider-Man Comics, “Spider-Man, Issue 15,” Marvel Comics, 1962.

[128] Network Security Journal, “Threats in the Era of Virtual 5G,” Network Security Journal 22, no. 3 (2020): 189-205.

[129] Cyber Defense Magazine, “The Role of Service-Based Architecture in Cybersecurity,” Cyber Defense Magazine 10, no. 2 (2021): 45-60.

[130] Harvard Journal of Cybersecurity, “The Impact of IoT on Cyberspace,” Harvard Journal of Cybersecurity 15, no. 1 (2018): 12-28.

[131] “2022 Innovations Dialogue: AI Disruption, Peace, and Security,” UNIDIR, (September 29, 2023), Disarmament Is Evolving, https://unidir.org/event/2022-innovations-dialogue-ai-disruption-peace-and-security/.

[132] Cybersecurity Today, “Operation Cloud Hopper: Cyberattacks on MSPs,” Cybersecurity Today 8, no. 4 (2019): 321-335.

[133] Hans Speier, “The Effect of War on the Social Order,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 218 (1941): 87–96.

[134] Stephen Peter Rosen, “New Ways of War: Understanding Military Innovation,” International Security 13, no. 1 (1988): 134-168.