Abstract: Modern war is a complex endeavour. Operations have effects on several domains simultaneously and are not limited to the operational domains of land, air, sea, cyber and space. The information environment, with its three dimensions (informational, physical and cognitive), is a conceptual link between the MPECI instruments of power and the classic operational domains. Information superiority and, thus, generally securing and cultivating (cognitive) superiority is paramount to asserting interests without prioritising the use of physical force.

Problem statement: How to integrate the cognitive dimension in modern warfare?

So what?: The cognitive dimension should be researched and structurally integrated into decision-making processes and the training of officers. The cognitive dimension should be integrated as a leading and integrative dimension in the information environment instead of creating yet another standalone cognitive or human domain.

Source: shutterstock.com/Laurent T

The Human Mind as a Battlefield

The cognitive dimension is the area of the human mind that actors must target to influence others. This area is vital to changing thinking and behaviour in a way that benefits the actor. It is critical to address the cognitive level in every approach to raise, strengthen, and maintain our mental resilience; it is also vital to the awareness and defensibility of an individual, groups, and even societies.[1] The high speed and vast proliferation of digital and social media means cognitive warfare can affect large audiences quickly and easily, potentially allowing one to sway public opinion and gain an advantage in a conflict. Targets may not only be soldiers—whole populations can be weaponised by changing their insights, beliefs, decisions, and behaviours.[2] Influencing the adversary’s cognitive processes can weaken its resolve and create a reluctance to engage in conflict. Therefore, situational awareness is necessary to counter an adversary´s actions and to create positive emotive narratives to motivate one’s own people. Countering disinformation with facts alone is insufficient.

The Supreme Art of War is to Subdue the Enemy Without Fighting.

Sun Tzu

Sun Tzu’s dictum clarifies the goal of social interactions: asserting one’s will, ideally without using violence. The art of persuasion, rooted in human cognition, takes centre stage. The question is: How can knowledge of human perception be used to achieve cognitive superiority over opponents?

“Cognitive Superiority is the state of possessing and applying faster, deeper, and broader understanding and more effective decision-making than adversaries” (NATO´s working definition).[3]

Cognitive warfare is just one component of achieving cognitive superiority, which enhances the ability of military forces to ‘out-think’ their adversaries. This concept extends beyond the military to influence human communication, relationships, persuasion, motivation and information dissemination. In our technology-driven world, technology and artificial intelligence play a profound role in shaping opinions and creating risks and opportunities—especially for younger generations. The coercive impact of technology underscores the importance of persuasive communication.

Within this context, there are two key aspects to consider: the first involves bolstering one’s own population, decision-makers, and allies by enhancing their morale and determination to defend or protect themselves. The second aspect pertains to weakening or exerting influence on the adversary’s side in cognitive warfare, “the war for hearts and minds.” It is crucial to effect and change opposing forces’ attitudes while informing and protecting one’s own forces from influence. Additionally, positive framing strengthens the will to defend oneself and the military’s and society’s resilience. This positive framing promotes cohesion, community values, and active advocacy for desirable norms.[4]

In essence, cognitive superiority is a product of intentional efforts, further underlining its significance in contemporary contexts. Establishing and cultivating significant advantages in terms of cognitive abilities such as perception, reasoning, problem-solving, decision-making, and memory is not a state that exists by chance. Reaching a steady state in Cognitive Superiority is a rather deliberate outcome. Cognitive superiority is intentionally pursued through strategies and tactics to influence, disrupt, or enhance cognitive processes to achieve a desired outcome.

NATO defines Cognitive Warfare as follows:“Activities conducted in synchronisation with other Instruments of Power, to affect attitudes and behaviour by influencing, protecting, or disrupting individual and group cognition to gain advantage over an adversary.”[5]

Activities conducted in synchronisation with other Instruments of Power, to affect attitudes and behaviour by influencing, protecting, or disrupting individual and group cognition to gain advantage over an adversary.

NATO’s definition refers to what we consider to be a crucial factor: Cognitive superiority, cognitive warfare, and cognition are power instruments in a phase-dependent conflict. This raises the question of the intended and unintended effects of state actors and their effectors.

Development of Domains

Clausewitz’s statement that war is a “continuation of politics by other means” expresses the military’s essential role as a factor and instrument of power, particularly following diplomacy as a political instrument. This can be seen, for example, in the use of naval units as a means of international power projection.

Following the First World War, air forces gradually joined land and naval forces, initially integrating their aircraft with the other branches until — in most countries — they became independent services in their own right. In the U.S., for example, the U.S. National Security Act of 1947 established and tried to deconflict the three services as the Army, Navy and Air Force under a joint high command — The Joint Chiefs of Staff.[6] The addition of cyber and space forces did not simplify matters regarding roles, missions, resources, interfaces and the necessary coordination between these services.[7] Implementing operational domains was the concept of (spatially) deconflicting military forces while enabling cross-domain coordination for common objectives.[8]

Most countries now recognise five operational domains: land, maritime, air, space, and cyberspace. Some also consider the information environment and the electromagnetic spectrum as domains. Moreover, other countries like Poland and Spain consider the cognitive as a domain.[9] Domains are a concept for allocating military forces and achieving coordinated effects across them (multi-domain operations).[10]

Confusion has been caused by the misleading usage of the terms “domain” and “dimension”, as “domain” usually means “area” and does not always have a military context. “Domain” forms the umbrella term, while “dimension” describes internal aspects of it. An example is the subdivision of the term Information Environment, as explained below.

As a singular instrument of power in conflicts, the military underscores the necessity for coordinated impacts across domains. The pure military domain distinction does not help, as all instruments of power can operate effectively within their respective domains. There are various perspectives about the instruments for an actor. The U.S. military and NATO recognise Diplomatic, Informational, Military, and Economic (DIME) as instruments of national power. A more extensive model is the Military, Political, Economic, Civilian, and Informational (MPECI) spectrum. MPECI operates within the Political, Military, Economic, Social, Infrastructure and Informational (PMESII) spheres.

As a singular instrument of power in conflicts, the military underscores the necessity for coordinated impacts across domains.

This holistic understanding reveals that:

- All power instruments are essential in varying degrees for comprehensive state solutions;

- These instruments can take effect across domains; and

- The central role of data and information in the Information Environment becomes apparent as a central, unifying element.

Holistic View of the Operational Environment (adapted from Jared Donnelly/Jon Farley, “Defining the ‘Domain’ in Multi-Domain”, Joint Air & Space Power Conference 2019, June, 2019, https://www.japcc.org/essays/defining-the-domain-in-multi-domain/)

This leads to the definition of a domain: A “Domain” – is “a defined sphere where distinct groups of specific activities are undertaken. Contained within a domain are specific activities, and their effects, orientated to achieve specific objectives (activities within a domain could include planning, execution, sustainment and redeployment).”[11]

The Information Environment (IE)

The IE is interwoven with the instruments of power (MPECI) across all domains. A few nations like Austria, France and Switzerland recognise it as autonomous, and its importance is the basis for effective action through data procession.[12] Notably, human cognition faces constraints in processing negative thoughts—an analogy being the “pink elephant” phenomenon.[13]

Models depict complex processes such as the “Information Environment” presented here. These create and guarantee correct and intentional understandings and interpretations of information, regardless of the diversity of data and information recipients. It is necessary to design the optimal message for the audience, place and time, considering individual mindsets, thus guaranteeing the most effective desired impact on the recipient’s behaviour. Therefore, understanding of human cognition is crucial.

For all the similarities in the nature of interpersonal or interstate conflict resolution, the “character”, mode, and the means and media of power used in the IE changed.[14] In the 20th/21st centuries, this character experienced a far-reaching change through new communication options and means of generating, preparing and processing information. This is reflected, for example, in the fact that one can speak of a “knowledge or information society”.[15]

In the 20th/21st centuries, this character experienced a far-reaching change through new communication options and means of generating, preparing and processing information.

NATO defines the Information Environment (IE) thus: “IE is comprised of the information itself, the individuals, organizations and systems that receive, process and convey the information, and the cognitive, virtual and physical space in which this occurs.”[16]

The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) goes deeper with its definition: “The IE is comprised of and aggregates numerous social, cultural, cognitive, technical, and physical attributes that act upon and impact knowledge, understanding, beliefs, world views, and, ultimately, actions of an individual, group, system, community, or organization. The IE also includes technical systems and their use of data. The IE directly affects and transcends all OE [Operational Environments].”[17]

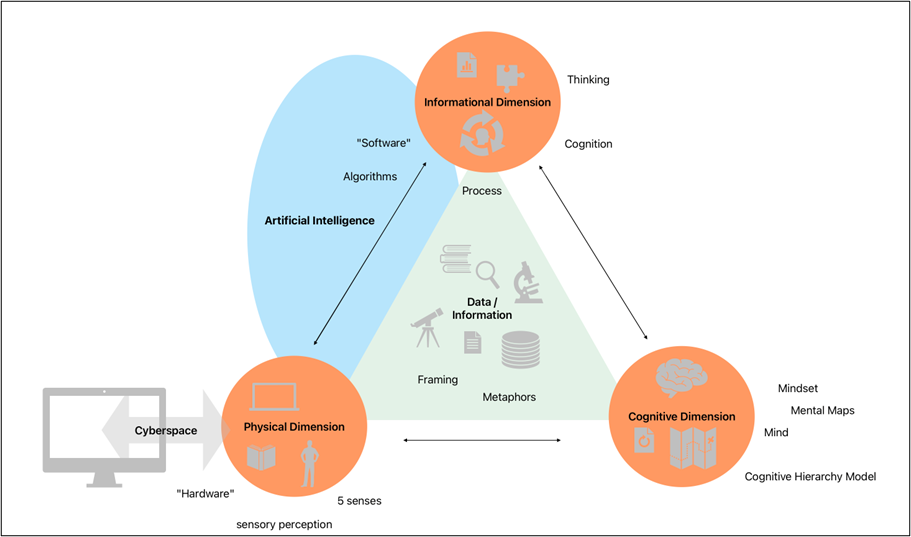

As an overarching all-embracing and all-pervading concept, the IE permeates all domains since warfare and human beings, as we understand them, would not be present without the perception of data that is processed to information. To further examine the analytic framework from this perspective, the question is how one could conceptualise the functional trinity of IE’s constituting dimensions: (1) Physical, (2) Informational and (3) Cognitive.

Functional Trinity of the Information Environment

IE’s Three Functional Dimensions

The U.S. Joint Concept for Operating in the Information Environment (JCOIE) describes the complexity and interaction of these three dimensions as follows: “The transmission-centric model deconstructs the IE into three separate dimensions through which data flows. The description of the informational dimension is also part of the description of the other two dimensions so it becomes difficult to distinguish. The informational dimension is where we collect, process, store, disseminate, and protect information. However, humans and computers perform these five functions in both the physical and cognitive dimensions. This construct works well in analyzing how data flows through information systems and networks to reach a receiver but becomes problematic when trying to understand the meaning activities communicate in a pervasive and dynamic IE. Because this model focuses on the flow of information, it separates the mind (cognitive) from the body (physical), and the thoughts (informational) from the mind (cognitive).”[18]

The premise is that data and information are the basic units for drawing conclusions. The concept of information lacks a clear definition and finds meaning in specific contexts. Data—collected through systematic or random observation—serves as the raw material for information. This elevated form of data, referred to as “information,” is structured, organised, and processed to take shape as ideas, hypotheses, and theories. This process of selecting and organising data into information represents the shift from perception to influence. As such, information encapsulates assumptions about perceptions that make a difference.[19]

This understanding of information allows a nuanced perspective on the Information Environment, consisting of three interrelated dimensions. These dimensions vary across situations and cases and affect decisions and actions. To better understand and implement them, specific analytical distinctions can be introduced:

- The Physical Dimension is a normative dimension where condensed observations/perceptions are core to communication. In this context, information is, in a sense, the product or artefact perceived by the recipient via its senses. This dimension encompasses the places where data is collected, processed, shared and stored, including data centres or network nodes, and conventional media such as printed materials.[20] People, as information carriers, form part of this dimension. Defensive measures involve protecting physical infrastructure on-site and in cyberspace, while offensive actions target disruption or destruction of physical facilities.

- The Informational Dimension is the dimension that covers data processing. Data processing includes perceiving, selecting, organising, and understanding (in the sense of differentiation through oscillation between perception in the physical dimension and reflection), thereby illustrating the dynamic aspects of information processing. Influences on this dimension affect data integrity, analysis, and processing, both defensively and offensively.

- The Cognitive Dimension is the dimension where individual cognitive systems form social systems (self-referential and self-reproductive). This is achieved through structurally coupled, adaptable communication operations, which further evolve and specialise into functionally differentiated subsystems and operate according to their functional logic.

The cognitive dimension is central; it is where information primarily impacts human cognition, involving perception, understanding, knowledge, beliefs, and values. The cognitive dimension exists within the consciousness of individuals and groups that receive information and influence decision-making and behaviour. Controlling cognitive-mental structures enables behaviour control, making propaganda, advertising, and social media key tools in the cognitive dimension. This dimension is essential for shaping narratives, for instance, in the context of the Ukraine conflict.[21]

The complexity of the IE arises from the interplay and interdependence of data, information, and the three dimensions. It is impractical to isolate single elements like the human or cognitive as separate domains, especially considering that the IE already encompasses these aspects. Naming the IE itself as a domain makes more sense, as all other domains rely on information, its processing, and human decision-making. Despite being technically augmented, politics and war remain realms of human action.

The complexity of the IE arises from the interplay and interdependence of data, information, and the three dimensions. It is impractical to isolate single elements like the human or cognitive as separate domains, especially considering that the IE already encompasses these aspects.

The metaphor of a football game can illustrate this. A football match consists of specific physical and psychological requirements and a set of rules. There is no match without a ball — this is the data carrier. The ball is the link to the ball-carrying player and individually interprets data into information for teammates and opponents. Even players without a ball offer information to all (offside position, potential pass target) due to spatial arrangement and game strategy. The audience, divided between home and opposing fans, participates and conveys information too — through cheers or boos. Coaches, staff, infrastructure, daily temperature, the overall atmosphere, signs, banners, smoke, security guards, the canteen’s beer, chants and more — all these environmental influences impact the gameplay and the flow of information. None can be singled out — all together, they define a football match.

In the context of high-stakes football matches, the IE plays a significant role; it can be seen as a metaphor comparable to steps of Cognitive Warfare. It encompasses various aspects:

- Data Gathering: Teams collect opponent data, including performance history, player stats, and tactical insights;

- Pre-match Analysis: Sports analysts and fans discuss match outcomes on social media;

- Decision-Making: Coaches decide line-ups and strategies based on data;

- Multi-dimensional Aspects: Factors like physical and psychological elements and crowd energy influence the atmosphere;

- Live Broadcast: Television commentary enhances viewer understanding;

- Fan Engagement: Fans share emotions and opinions on social platforms also on the spot in and around the stadium— including irrational, emotionally driven violence

- In-match Analysis: Analysts provide real-time insights;

- Player Metrics: Technology tracks player performance in real-time;

- Post-match Analysis: Coaches, players, and fans dissect match results.

With this example, it becomes evident that effective interventions face challenges due to the multiple and often contradictory stimuli in the IE. These affect the intricate human brain and lead to unpredictable decisions due to their complexity. Behavioural measures of the cognitive dimension face difficulties due to numerous cognitive biases, of which around 200 have been identified.[22]

Zooming In On the Specifics Of the IE

Human communication consists of symbols, which—through syntax—also become machine-readable data. When data become subjectively relevant, new and important for a receiver, they become information. Through networking, processing and saving information with experience, knowledge is created. Information develops through processing, editing, and analysing significant data for the recipient. They are cognitively processed, integrated into the IE, and shared with others, provided they are not protected.

Human communication consists of symbols, which—through syntax—also become machine-readable data. When data become subjectively relevant, new and important for a receiver, they become information.

Since cognitive superiority and cognitive warfare target humans, we focus on the interaction of the informational and cognitive dimensions. We disregard technical aspects like “soft- and hardware” and instead emphasise the human body as a sensor for perception and communication.

Zooming In On the Informational Dimension

Data processing in this dimension is crucial, but it is essential to recognise that “perception” subjectively colours information in the eye of the beholder and more than 98 per cent (!) of human thinking happens unconsciously.[23] Cognition is the “mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses.”[24] Decisions are based on “gut feeling” (intuition), experience, and attitude, according to the Cognitive Hierarchy Model.

In addition, perceptions and actions are based on metaphors and frames, filtering and transmitting information aligned with our beliefs.[25] These must be consistent with the appropriate frame for behavioural and attitudinal change to occur.

An experiment conducted during U.S. presidential elections in 2004 illustrated this phenomenon: supporters of one nominee recognised only the proven lies of the opposing candidate but not those of their own favourite.[26] Rather than facts, emotions play a major role in this process,[27] and their cultural interpretation varies.[28] Transmitters in this process are metaphors, which are linguistic images transferring a concept from one context to another, giving messages via human sensory channels[29] a lively and intense meaning.[30] Examples include “time flies”, ” wall of silence”, or “snail’s pace.” The choice of words is crucial in framing effects. For example, “tax relief” suggests the relief from oppressive taxes that are perceived as unfavourable, while “tax contribution” is seen as socially beneficial.[31]

In the same way, words inside a text can influence our behaviour unconsciously. Terms like “aggressive” and “push” imply unfriendliness, while “polite” and “respect” create positivity. Likewise, reading reports about older people or leisure activities can also influence our movement speed immediately afterwards.[32]

Let us move to another aspect of human behaviour: People act mainly irrationally, often following the majority.[33] Psychologist Solomon Asch’s conformity experiment shows how people tend to conform to the majority even when it defies logic, mostly in conformity of adjustment, not attitudinal.[34] Also, announcements of survey results often lead to alignment with the published majority opinion.[35] Conversely, people may join a minority view, especially if it satisfies their need for distinctiveness, including so-called conspiracy theory followers.[36]

People act mainly irrationally, often following the majority. Psychologist Solomon Asch’s conformity experiment shows how people tend to conform to the majority even when it defies logic, mostly in conformity of adjustment, not attitudinal.

Looking into today’s technology-driven world, information overload can lead to self-imposed isolation, with people hiding in their own “bubbles”, creating echo chambers where only similar views can enter.[37] For attitude changes, the filter must be dodged positively because negative criticism increases undesired behaviours,[38] for example, conspiracy theorists who isolate themselves and reject observable reality.[39] Such behaviour can fuel society’s polarisation and threaten its unity.[40] Therefore, positive emotional framings and metaphors are necessary to promote desired behaviour, while fear creates only a short-term effect.[41]

The environment also influences decisions,[42] as, for example, heat makes people more aggressive and decisions more severe.[43] This environmental impact is also applicable when your favourite sports team loses.[44]

Regarding how environmental factors impact decision-making, it is important to consider how terms can significantly shape public attitudes. The term “Islam” can inadvertently evoke rejection and violence, while “Islamophobia” implies disgust, fear, and aversion towards Muslims, often fueled by media reports.[45] Similarly, the phrase “Islamic State” associates “Islam” with terrorism through media coverage, reinforcing antipathy.[46] Similar frame distortions are seen in the metaphor “refugee crisis,” which shifts the focus to refugees as the trigger of the crisis rather than the underlying cause, e.g., war in their home country. Therefore, more accurate terms could be “violence crisis” or”displacement crisis” to clarify the causes.[47]

Beyond crisis terminology, strategic communication plays a key role in shaping public perception and political discourse. From this perspective, the George W. Bush administration’s strategic use of metaphors after the 9/11 attacks, particularly the “War on Terror”, skillfully avoided direct references to “War on Iraq”.[48] This consistent message in the media, combined with the heroic portrait of soldiers, led to a significant increase in military recruitment and record-high government approval ratings.

This example of the U.S. shows that political framing can increase the population’s motivation. The outcome would increase even more by using positive emotional metaphors, such as “Solidarity creates Security”. Thereby, social cohesion can be promoted through strategic communication in close cooperation with the media. Values and norms for which solidarity is collectively demonstrated should be communicated emotionally. Solidarity is presented as a desirable alternative to society’s egocentric orientation, aiming to promote cross-border cooperation and mutual support.[49] Initially, conflicting frames can coexist as they provide the basis for discourse. However, if a particular framing is no longer used, it gradually disappears.[50]

Social cohesion can be promoted through strategic communication in close cooperation with the media. Values and norms for which solidarity is collectively demonstrated should be communicated emotionally.

Zooming In On the Cognitive Dimension

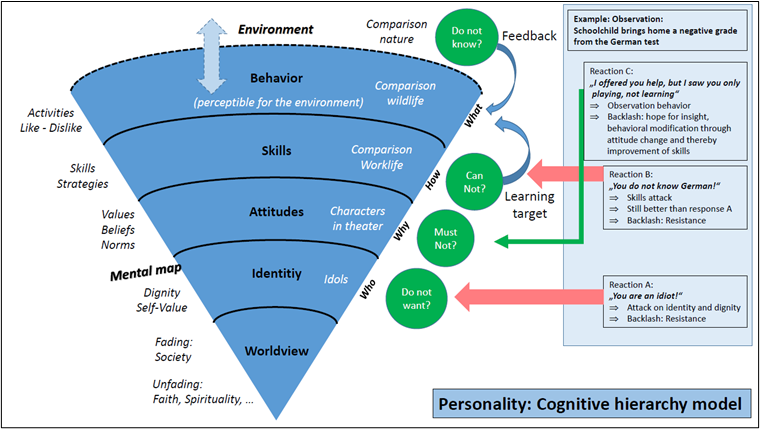

In the cognitive dimension, creators aim to design messages and strategies that resonate with an individual’s cognitive world. This process can range from one-time actions to profound attitude changes, as depicted in the cognitive hierarchy model.

The Cognitive Hierarchy Model

This model’s functioning can be exemplified through real-world experiences. Examples include the radicalisation of women from Western societies, where actors particularly focus on transforming their worldviews, attitudes, values, and norms. The case of Muriel Degauque exemplifies this well. Born in Belgium in 1967 and raised as a Roman Catholic, she illustrates the impact of extremist ideologies and propaganda on cognitive maps, ultimately leading to her suicide bombing in Iraq in 2005.[51]

- Information Processing: Muriel was exposed to extremist ideas and propaganda, challenging her existing beliefs and leading her to reevaluate her worldview.

- Cognitive Mapping: Her perception of the world shifted as she consumed extremist content and engaged with radicals, aligning herself more closely with extremist ideologies.

- Cognitive Warfare: Extremist groups manipulate individuals like Muriel by creating narratives that exploit vulnerabilities and create a sense of identity and belonging.

- Cognitive Hierarchy Model: Muriel’s inner cognitive layers, including beliefs and identity, underwent a significant transformation that led her to embrace extremist beliefs.

- Behavioural Manifestation: Her radicalisation resulted in the decision to become a suicide bomber, a direct result of her transformed cognitive map and hierarchy.

- Difficulty of Change: Changing deeply entrenched behaviours in the cognitive hierarchy is challenging, highlighting the need for preventive efforts and intervention programmes.

In essence, navigating behaviour change requires a nuanced approach across these levels. In summary, Muriel’s identity change highlights the impact of extremist ideologies on individuals’ beliefs and behaviours and the challenges of countering radicalisation once it reaches deep cognitive layers, emphasising the importance of prevention and intervention.[52]

Moving from understanding extremist ideologies and the importance of prevention, let us examine the “cognitive dimensions” central role in shaping beliefs, decisions, actions and the broader social context.

Perception filters and structures environment stimuli, with inherent biases influencing decisions. These processes are often unconscious, and models like the “Cognitive Hierarchy Model” simplify this complexity. Placing the cognitive dimension within the broader societal framework is evident in political framing,[53] which strategically establishes interpretative frameworks to structure the world’s meaning.[54] This communicative approach involves media actors, whether through state propaganda, traditional media, or social platforms.[55]

Perception filters and structures environment stimuli, with inherent biases influencing decisions. These processes are often unconscious, and models like the “Cognitive Hierarchy Model” simplify this complexity.

In Russia’s war against Ukraine, Russia and Ukraine are engaged in a battle of narratives to shape perceptions and attitudes in target countries, including public opinion, the media and politicians.[56] Russia aims to undermine Ukraine’s strategy of attracting Western support by using narratives such as a coup in Ukraine, NATO’s aggressive expansion and the denial of Ukraine’s historical independence from Russia. Meanwhile, Ukraine is trying to do the opposite by emphasising an imminent invasion, portraying the Kremlin as a cynical and crazy regime, highlighting Russia’s propaganda efforts and emphasising Ukraine’s cultural affinity with the West.[57] This illustrates the close link between the political sphere and strategic military planning. The dynamic between these narratives and counter-narratives is complex and challenging, posing difficulties for politico-military analysis and real-time decision-making.[58]

The tension between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Taiwan exemplifies another multifaceted CW approach. The PRC employs a broad set of tools and tactics like military intimidation, bilateral exchanges for influence, religious interference, and internet-based disinformation campaigns to influence information processing and decision-making, ultimately aiming “to control what’s between the ears”.[59] These strategies exhibit a discernible, systematic pattern of operation characterised by a characteristic sequence of actions: threatening, attracting and distracting.[60] Threatening tactics are employed to apply psychological pressure on opponents of PRC policies. Meanwhile, activities in the attraction sphere aim to entice Taiwanese talent and investors to relocate to China for residence and employment opportunities. Distraction then involves engaging in activities that create confusion on particular topics that could gain popularity or become widely shared within specific target groups. As an example of distraction tactics, the deliberate spread of false information in May 2021, suggesting that the hand disinfectants used by the Taiwanese government were toxic, stands out. This is a clear case of intentional actions that generate confusion and undermine trust.[61]

These different showcases illustrate the character of information as a means. For instance, in a military context, information may be conveyed through troop movements, requiring perception, processing, interpretation, and decision-making. The complexity of these actions highlights the challenges, especially for military leaders in conflict situations. Exploring ways to enhance cognitive processing through neuroscientific and technical insights has become a topic of discussion.[62]

The Importance of Cognitive Warfare and Motivation

Cognitive warfare, which seeks to shape thought and behaviour through the targeted use of information technologies, is becoming increasingly important in modern conflicts. Exploring this intersection of military thought and action has profound implications, amounting to a paradigm shift. Navigating the challenges of influence requires understanding how the dimensions of the Information Environment interact. This is critical to orchestrating military capabilities and managing warfare in evolving conflicts. Achieving and maintaining cognitive superiority requires an understanding of the mechanics and dynamics of the IE to exploit the benefits of cognitive warfare fully. Six aspects make the case for using cognitive warfare tools within the IE:

- The non-physical tactics of cognitive warfare reduce damage to people and infrastructure. This appeals to actors seeking to achieve objectives without traditional military means, such as using psychology, neuroscience and technology to influence emotions and behaviour;

- With the rise of social media and online platforms, cognitive warfare quickly influences a wide audience, shaping public opinion to the conflict’s advantage;[63]

- Conducting cognitive warfare covertly obscures information sources, making attribution complex. It includes misinformation, cyber-attacks, social manipulation, and influence operations;

- Cognitive warfare allows one side to shape the narrative of a conflict, potentially influencing how the international community perceives it;

- Cognitive warfare has lower financial and logistical costs compared to conventional military operations; and

- The effects of cognitive warfare persist, potentially shaping target audiences and societies for years after the initial campaign.

Navigating the challenges of influence requires understanding how the dimensions of the Information Environment interact. This is critical to orchestrating military capabilities and managing warfare in evolving conflicts.

Emphasising the use of tools within the IE to change the will to fight and defeat opponents requires a systematic approach to exerting influence. Key activities such as behavioural change can bring planned transformation and programmed change to target groups. One has at first to frame a message with appropriate language models, metaphors, and cues that will resonate with the recipient in an intended way. Second, one needs to address the cognitive hierarchy’s corresponding (base) layer so that the carefully crafted messages connect at some fundamental level with the recipient and start (re)shaping mental maps in the cognitive dimension.[64]

Enhanced cognitive capabilities can be achieved by prioritising cognitive operations and training personnel in cognitive skills such as information analysis, social media engagement, and influence operations. In addition, military capability planners can work closely with experts in psychology (advertising/marketing, public affairs, campaigning), neuroscience, and information technology to develop effective cognitive tactics and strategies.

In this regard, the extremism researcher Julia Ebner, with other experts, has devised a methodical five-step approach for this process of change in cooperation:[65]

- Start with established points of contact with perceptions, beliefs and attitudes: psychological, social and technological—counter identity convergence trends and radicalisation; offer attractive alternatives to provide an alternative platform for exclusivity and a sense of belonging, offer recognition and appreciation;

- Bringing stakeholders together to influence the perception of the (political, diplomatic, socio-economical or interpersonal) situations and relationships such that one can create conditions conducive to peaceful conflict resolution and forge alliances of action, network with people from the field and involve the business community;

- Appeal to all generations: from Generation Alpha to digital nomads;

- Reversing the trend: reclaiming the language—creating language images through the increased involvement of linguists and bringing in multipliers and influencers from the military, religion, and sports; furthermore, reporting opportunism and exposing disinformation at an early stage and taking countermeasures (“pre-bunks”);

- Align with a tangible and attainable vision of the future: Rebuild trust — fact-based science is insufficient because trust is primarily based on feelings and emotions and relates to identity. Change has to be about this: real-time research, such as cross-platform big-data analysis, ethnographic in-depth analysis, open-source intelligence research, and data collection; and finally — responding to tech trends, especially Artificial Intelligence opportunities.

As an example of a successful process of change, the gradual reintegration of members of the FARC through deliberate accents on the emotional level, as well as a policy of forgiveness and alternative offers since 2006, and ultimately, the peaceful dissolution of the violent arm of this organisation in 2016 in Colombia, can be seen:[66]

- Acknowledging the trauma: recognising the emotional scars of conflict, Colombia prioritised healing as the foundation of peace;

- Policy of forgiveness: By offering amnesty for minor violations, Colombia underscored its commitment to breaking the cycle of violence;

- By providing education and employment opportunities, this approach empowered former combatants to choose a different path;

- Humanisation by sharing the fighters’ stories to counter stereotypes and build empathy;

- Community engagement: Involving local communities made reintegration easier and created a sense of unity;

- Through global collaboration, valuable expertise was brought to the process;

- Political change: Allowing FARC members to participate in politics allowed them to channel their advocacy peacefully;

- Holistic strategy: Addressing root causes prevents future conflict;

- Symbolic transformation: the FARC gradually evolved from an insurgency to a political party.

In sum, the reintegration of FARC members represents a triumph of conflict resolution and underscores the profound importance of embracing compassion, second chances and non-violent pathways.

Conclusions and the Way Ahead

In the field of communication and conflict resolution, the meaning of data and information is of great importance. Communication involves giving orders, exchanging data and informing forces. At the same time, cognitive warfare seeks to influence adversaries to positively change behaviours without resorting to physical force. Cognitive superiority goes beyond this to include creating narratives and metaphors to align forces with values and norms, requiring an awareness of influence and resilience. Effective influence requires understanding thought processes, cultural nuances and shifting worldviews because there is no one-size-fits-all solution. It takes time, trust, appropriate narratives and positive framing. Societal conviction of the need for action is essential for unity and to prevent the loss of trust in politics. Society is a strong instrument of power—recruiting for the military and providing resources for conflict resolution. Therefore, it must be integrated. For instance, the Austrian concept of “Geistige Landesverteidigung” (mental and moral national defence) emphasises cognitive superiority as a base for comprehensive national defence (“Umfassende Landesverteidigung”). This latter point also includes economic, civil, and military dimensions. This includes the pursuit of cognitive superiority, closely linked to the other aspects of comprehensive national defence. These reflections on the complex IE prove there is no added value in isolating individual elements, such as creating a cognitive or human domain. As representatives of the cognitive aspect, humans remain the recipients of all actions in the domains.

The Austrian concept of “Geistige Landesverteidigung” emphasises cognitive superiority as a base for comprehensive national defence. This latter point also includes economic, civil, and military dimensions.

As Clausewitz recognised, the ultimate goal of military operations lies in the sphere of politics, in which social and human coexistence is consciously shaped both domestically and internationally.[67] Information has the same function as the IE’s three Physical, Informational and cognitive dimensions. It is similar to the ball in a football game. The close interaction between these dimensions is decisive for metaphorically scoring the final goal and establishing cognitive superiority.

Bernhard Schulyok has research interests in Security Policy and Military Capability Development. His publications include three handbooks and numerous individual articles in the journal “Truppendienst “and the online journal “The Defence Horizon Journal”. Bernhard is the Austrian National Director of the multinational platform Military Capability Development Campaign (MCDC).

Lukas Grangl has research interests in Security Policy, International Politics, and Military Policy. He has published work on the application and implementation of modern control concepts (e.g. New Public Management). He is a member of the Reserve Forces of the Austrian Armed Forces and a manager of a real estate subsidiary of an Austrian bank.

Markus Gruberhas research interests in International Politics, Foreign Policy Analysis, Diplomacy, Systems Theory (in International Relations), and Conflict and Security analysis. He is a member of the Reserve Forces of the Austrian Armed Forces and business unit manager of an Austrian scale-up for access management and control.

The views contained in this article are the authors’ alone and do not represent the views of the Federal Ministry of Defence.

[1] David Pappalardo, “Win the War before the War?: A French Perspective on Cognitive Warfare,” War on the Rocks, last modified August 01, 2022, https://warontherocks.com/2022/08/win-the-war-before-the-war-a-french-perspective-on-cognitive-warfare/.

[2] Hervé Le Guyader, “Cognitive Warfare: The Future of Cognitive Dominance/ Chapter 3 – Cognitive Domain: A sixth Domain of Operations?,” last modified April 08, 2022; NATO Scientific Meeting on Cognitive Warfare (France, June, 2021), https://hal.science/hal-03635898/document#:~:text=Chapter%203%20%E2%80%93%20COGNITIVE%20DOMAIN%3A%20A%20SIXTH%20DOMAIN%20OF%20OPERATIONS%3F&text=%E2%80%9CThe%20sixth%20domain%2C%20a%20domain,always%20costly%2C%20often%20risky.%E2%80%9D&text=The%20concept%20for%20a%20sixth,at%20the%20beginning%20of%202020.

[3] NATO, “Cognitive Warfare Exploratory Concept,” Version 1.0, last modified May 2023.

[4] George Lakoff and Elisabeth Wehling, Auf leisen Sohlen ins Gehirn. Politische Sprache und ihre heimliche Macht (Heidelberg: Carl-Auer-Systeme Verlag, 2016), 183-85.

[5] NATO, “Cognitive Warfare Exploratory Concept,” Version 1.0, last modified May 2023.

[6] Act of July 26, 1947 (“National Security Act”), Public Law 80-253, 61 STAT 495, https://legacy.catalog.archives.gov/id/299856.

[7] Erik Heftye, “Multi-Domain Confusion: All Domains Are Not Created Equal,” Real Clear Defense, last modified May 26, 2017, https://www.realcleardefense.com/articles/2017/05/26/multi-domain_confusion_all_domains_are_not_created_equal_111463.html; Michael P. Kreuzer, “Cyberspace is an Analogy, Not a Domain: Rethinking Domains and Layers of Warfare for the Information Age,” The Strategy Bridge, last modified July 08, 2021, https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2021/7/8/cyberspace-is-an-analogy-not-a-domain-rethinking-domains-and-layers-of-warfare-for-the-information-age#amp_ct=1680709685889&_tf=Von%20%251%24s&aoh=16807066995939&referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com&share=https%3A%2F%2Fthestrategybridge.org%2Fthe-bridge%2F2021%2F7%2F8%2Fcyberspace-is-an-analogy-not-a-domain-rethinking-domains-and-layers-of-warfare-for-the-information-age.

[8] First necessities to deconflict services see Key West Agreement 1948, https://books.google.be/books?id=uC1I3vTSaEsC&dq=Pace-Finletter+MOU+1952&pg=PA151&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Pace-Finletter%20MOU%201952&f=false; Joint Vision 2020, (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, April 08, 2013), http://www.pipr.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/jv2020-2.pdf.

[9] Multinational Capability Development Campaign (MCDC), Multi-Domain Multinational Understanding, last modified November 2022, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1128898/MCDC_MDI.pdf.

[10] Idem.

[11] Idem.

[12] Idem.

[13] Lakoff and Wehling, Auf leisen Sohlen ins Gehirn. Politische Sprache und ihre heimliche Macht, 76-78. The book provides an overview of the subject and offers numerous examples.

[14] NATO (2017), AJP-06 Allied Joint Doctrine for Communication and Information Systems.

[15] Anna Engelhardt and Laura Kajetzke, (Hrsg.), Handbuch Wissensgesellschaft. Theorien, Themen und Probleme (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2010).

[16] NATO (2018), MC 422/6 NATO Military Policy for Information Operations.

[17] US DoD (2018), Joint Concept for Operating in the Information Environment (JCOIE).

[18] Idem.

[19] Gregory Bateson, Geist und Natur. Eine notwendige Einheit (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 1979), 122-132.

[20] Lawrence A. Kuznar, “21st Century Information Environment Trends out to 2040: The Challenges and Opportunities in the Integration of Its Physical, Cognitive, and Virtual Dimensions,” Open Publications 8, no. 1 (2023), 10–14. The author represents a strong focus on technological aspects and emphasizes cross-references to the cyber dimension.

[21] Lothar Riedl, “Social Media und Kriegspropaganda am Beispiel des Ukrainekrieges,“ ÖMZ 3 (2023): 283–300.

[22] Phil Dixon and Scott Fitzgerald, Understand Your Brain: For a Change: Discover the Hidden Forces Driving Your Behavior (Oxford: Oxford Brain Institute Press, 2019).

[23] Elisabeth Wehling, Politisches Framing. Wie eine Nation sich ihr Denken einredet – und daraus Politik macht (Berlin: Verlag Ullstein, 2021), 48.

[24] “Cognition,” Oxford University Press and Dictionary, accessed August 11, 2023, https://www.lexico.com/definition/cognition.

[25] Lakoff and Wehling, Auf leisen Sohlen ins Gehirn. Politische Sprache und ihre heimliche Macht, 71-74.

[26] Ibid, 73.

[27] Elisabeth Wehling, Politisches Framing. Wie eine Nation sich ihr Denken einredet – und daraus Politik macht, 45.

[28] George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Leben in Metaphern. Konstruktion und Gebrauch von Sprachbildern (Heidelberg: Carl-Auer-Systeme Verlag, 2016), 164-65.

[29] Elisabeth Wehling, Politisches Framing. Wie eine Nation sich ihr Denken einredet – und daraus Politik macht, 21.

[30] Georg Lakoff and Elisabeth Wehling, Auf leisen Sohlen ins Gehirn. Politische Sprache und ihre heimliche Macht, 13-31.

[31] Elisabeth Wehling, Politisches Framing. Wie eine Nation sich ihr Denken einredet – und daraus Politik macht, 104-107.

[32] Ibid, 37-41.

[33] Rutger Bregman, Im Grunde gut. Eine neue Geschichte der Menschheit, (Hamburg: Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, 7. Auflage, 2022), 289.

[34] Deborah Felicitas Thoben and Hans-Peter Erb, “Wie es euch gefällt: Sozialer Einfluss durch Mehrheiten und Minderheiten,“ The Inquisitive Mind, no. 2 (2010), https://de.in-mind.org/article/wie-es-euch-gefaellt-sozialer-einfluss-durch-mehrheiten-und-minderheiten.

[35] Idem.

[36] Idem.

[37] Georg Lakoff and Elisabeth Wehling, Auf leisen Sohlen ins Gehirn. Politische Sprache und ihre heimliche Macht, 71-72.

[38] Elisabeth Wehling, Politisches Framing. Wie eine Nation sich ihr Denken einredet – und daraus Politik macht, 57.

[39] Georg Lakoff and Elisabeth Wehling, Auf leisen Sohlen ins Gehirn. Politische Sprache und ihre heimliche Macht, 81.

[40] Julia Ebner, Massenradikalisierung (Berlin: Suhrkamp Verlag, AG, 2023), 212-214.

[41] Georg Lakoff and Elisabeth Wehling, Auf leisen Sohlen ins Gehirn. Politische Sprache und ihre heimliche Macht, 134-35.

[42] Shai Danzinger, Jonathan Levav and Liora Avanim –Pesso, “Extraneous Factors in Judical Decisions,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108, no. 17 (2017), 6889-92, in Noise. A Flaw in Human Judgement, edited by Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony and Cass R. Sunstein (New York: Little, Brown Spark, 2021), 23.

[43] Anthony Heyes and Sooedeh Saberian, “Temperature and Decisions: Evidence from 207,000 CourtCases,” American Econiomic Journal: Applied Economics 11, no. 2 (2018), 238-65, in Noise. A Flaw in Human Judgement, edited by Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony and Cass R. Sunstein (New York: Little, Brown Spark, 2021), 23.

[44] Eren Ozkan and Naci Mocan, “Emotional Judges and Unlucky Juveniles,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10, no. 3 (2018), 171-205, in Noise. A Flaw in Human Judgement, edited by Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony and Cass R. Sunstein (New York: Little, Brown Spark, 2021), 23.

[45] Elisabeth Wehling, Politisches Framing. Wie eine Nation sich ihr Denken einredet – und daraus Politik macht, 154-59.

[46] Ibid, 159-66.

[47] Ibid, 193-98.

[48] Frank Luntz, “Communicating the Principles of Prevention and Protection in the War on Terror,“ http://www.zephoria.org/lakoff/files/Luntz.pdf; George Lakoff and Elisabeth Wehling, Auf leisen Sohlen ins Gehirn. Politische Sprache und ihre heimliche Macht (Berlin: Verlag Ullstein, 2021), 134; John F. Harris and Brian Faler, “Talking Iraq: Some Things Are Better Left Unsaid,” The Washington Post (June 20, 2004), https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2004/06/20/talking-iraq-some-things-are-better-left-unsaid/32603065-ac90-48c4-9b31-b9bc80b62e84/.

[49] A survey among experts, primarily out of security policy, economic and military, revealed that neutrality is considered outdated in Austria, which is in contrast to public opinion. Therefore, strategic communication is challenged to promote a shift from (egocentric) neutrality to full solidarity within the EU, https://www.aies.at/publikationen/2023/studie-neutralitaet.php.

[50] Elisabeth Wehling, Politisches Framing. Wie eine Nation sich ihr Denken einredet – und daraus Politik macht, 59-60.

[51] Craig S. Smith, “Raised as Catholic in Belgium, She Died as a Muslim Bomber,” The New York Times (Dec 6, 2005), https://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/06/world/europe/raised-as-catholic-in-belgium-she-died-as-a-muslim-bomber.html.

[52] Edwin Bakker and Seran de Leede, “European Female Jihadists in Syria: Exploring an Under-Researched Topic,” research report (April 01, 2015), https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep17475.

[53] Elisabeth Wehling, Politisches Framing. Wie eine Nation sich ihr Denken einredet – und daraus Politik macht (Berlin: Verlag Ullstein, 2021).

[54] Stephen Reese, “The framing project: A bridging model for media research revisited,” Journal of Communication 57 (2007), 148–154.

[55] Regula Hänggli and Hanspeter Kriesi, “Political Framing Strategies and their Impact on Media Framing in a Swiss Direct-Democratic Campaign,” Political Communication 27 (2010), 141–157.

[56] Lothar Riedl, „Social Media und Kriegspropaganda am Beispiel des Ukrainekrieges,“ ÖMZ 3 (2023), 283–300; Bruno Hofbauer and Philipp Eder, “Krieg in der Ukraine – Erste militärstrategische Analysen,“ ÖMZ 4 (2022), 419–21.

[57] Lothar Riedl, „Social Media und Kriegspropaganda am Beispiel des Ukrainekrieges,“ ÖMZ 3 (2023), 290f.

[58] Lothar Riedl, „Social Media und Kriegspropaganda am Beispiel des Ukrainekrieges,“ ÖMZ 3 (2023), 283–300; Bruno Hofbauer and Philipp Eder, “Krieg in der Ukraine – Erste militärstrategische Analysen,“ ÖMZ 4 (2022), 419–21.

[59] Joyce Huang, “China Using ‘Cognitive Warfare’ Against Taiwan, Observers Say,“ https://www.voanews.com/, January 17, 2021, https://www.voanews.com/a/east-asia-pacific_china-using-cognitive-warfare-against-taiwan-observers-say/6200837.html

[60] Hung Tzu-Chieh and Hung Tzu-Wie, “How China’s Cognitive Warfare Works: A Frontline Perspective of Taiwan’s Anti-Disinformation Wars,” Journal of Global Security Studies 7/4 (2020), 1 – 18, 7

[61] Tzu-Chieh and Tzu-Wie, “How China’s Cognitive Warfare Works: A Frontline Perspective of Taiwan’s Anti-Disinformation Wars,” 1 – 18, 7

[62] NATO (2023), NIAG SG.278 Cognitive Augmentation for Military Applications.

[63] Influencing is a very challenging endeavour, since the opposing defence must be undermined, language barriers overcome, strategies for foreign cultural and religious spaces must be developed, etc. At the same time, an “Informational warrior” also competes with the general informational overload and faces the challenge of having to integrate the complexity of human perception into his strategy (biases, for example).

[64] Rutger Bregman, Im Grunde gut. Eine neue Geschichte der Menschheit, 395.

[65] Julia Ebner, Massenradikalisierung, 293-324.

[66] Rutger Bregman, Im Grunde gut. Eine neue Geschichte der Menschheit, 405-410.

[67] Carl von Clausewitz, Vom Kriege, (Hamburg: Nikol Verlag 2008), 34; 37-38.