Abstract: As a rising military and economic superpower, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has sought to assert its hegemony with gunboat and “Wolf-warrior” diplomacy, exemplified by the South China Sea (SCS) dispute. Numerous Southeast Asian (SEA) states perceive the PRC as having upended the regional security architecture and have sought to restrain it through supranational bodies and strategic partnerships with the United States (U.S.). Nevertheless, the competing agendas of the U.S. and PRC have reignited fears that the SCS dispute could snowball into a geopolitical flashpoint. While rapprochement by supranational bodies and the U.S. has prevented the disputes from spiralling out of control, the PRC’s increasingly provocative actions are an antecedent for regional conflagration.

Problem statement: How likely will the South China Sea dispute conflagrate into a regional conflict?

So what?: Southeast Asian (SEA) littoral states should pursue bilateral talks with the PRC to de-escalate the maritime disputes while recognising the U.S.’s role as a counterweight in the regional security architecture. At a regional level, SEA states need to establish Sea Lines of Communication based on a Rules-based International Order and push for a substantive and practical Code of Conduct with the PRC.

Historic Claims

Citing how the Xia Dynasty (an integral part of the PRC’s history) had governed the SCS,[1] the PRC has attempted to assert sovereignty over roughly 2.7 million square kilometres of contiguous waters with its ambiguous “Nine-dash Line”.[2] However, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which the PRC ratified in 1986, does not grant signatories the right to assert sovereignty based on historical legacy.[3] As the PRC’s claims impinge on their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ), Vietnam and the Philippines have sought diplomatic and legal recourse.[4] However, the PRC has been adamant in cooperating with them and has studiously avoided clarifying what the “Nine-dash Line” means.[5] Consequently, tensions between the littoral states have risen, and military skirmishes have become more frequent.[6]

The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which the PRC ratified in 1986, does not grant signatories the right to assert sovereignty based on historical legacy.

PRC Provocation: A Precedent for Conflict

The PRC has deployed ships into the disputed waters more frequently, igniting tensions significantly and increasing the prospect of a conflict. As naval resources are channelled to its core interests (such as harassing Taiwan), the PRC usually deploys fishing boats alongside the Coast Guard to assert territorial claims.[8] Hence, the deployment of its largest and most modern oil rig, Hai Yang Shi You 981, within Vietnam’s EEZ raises the stakes.[9]

The oil rig was ominously described by the chairman of the state-owned China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) as a “mobile national territory and strategic weapon”.[11] This oil rig could be used as an agent provocateur sent to analyse littoral states’ retaliatory actions. However, the PRC seemed uncertain of their response and dispatched it unannounced with 100 fishing and CNOOC-chartered ships.[12] The use of civilian vessels is a less contentious approach vis-à-vis warships, denying the U.S. a raison d’être to intervene militarily.[13] After all, both states have competing stakes in the region due to the region’s geo-strategic significance.[14]

Apart from sowing distrust, the PRC’s surprise deployment was interpreted as an act of provocation by Vietnam, which deployed nine Coast Guard Vessels.[15] Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc even told sailors to be “ready to fight”.[16] Without a Code of Conduct (CoC), tit-for-tat measures could spiral out of control quickly,[17] culminating with outright hostility.

An Antidote to Conflict

Amidst simmering tensions, regional blocs have played an important role in de-escalation, preventing an armed confrontation between claimants. Established in 1967, ASEAN aims to promote “commitment and collective responsibility in regional peace, security and prosperity”.[18] Members should engage in “consultations on matters seriously affecting the common interest of ASEAN”.[19] On this note, Vietnam and the Philippines have leveraged ASEAN to engage the PRC. A Declaration of Conduct (DoC) and Joint Working Group (JWG) were established in 2002 and 2005, respectively, paving the way for a Code of Conduct (CoC) to be negotiated.[20] While the DoC is not legally binding and has no dispute-resolution mechanism,[21] it remains a symbol of cooperation and lays the groundwork for future capacity-building initiatives.

Established in 1967, ASEAN aims to promote “commitment and collective responsibility in regional peace, security and prosperity”.

As regional blocs “promote shared regional norms”,[22] they are a force multiplier when like-minded states confront an adversary contravening shared values. This collective voice increases the credibility of SEA states, drawing the global community’s attention.[23] The United Kingdom, Germany, France and the Netherlands have recognised the threat the PRC poses and have increased their diplomatic and military footprint in the region.[24] The purpose of such bilateral visits and warship deployment must be analysed to determine the effect these European states have on the regional security architecture. In contrast to the British, French and Dutch diplomatic overtures (that focused heavily on defence cooperation),[25] Germany seemed to be more interested in diversifying and “de-risking” its economy from the PRC.[26] Therefore, Germany’s piecemeal efforts did little to appease SEA states amidst the prospect of Chinese aggression. Similarly, the deployment of the German warship “Bayern” avoided transiting through any contested sea route and crossing the path of allied warships in the region, unlike the British, French and Dutch navies that participated in military exercises with their SEA counterparts near the disputed waters.[27] For most European states, their presence can be regarded as a security counterweight by the SEA states. This creates a check-and-balance system, deterring the PRC from unilaterally expanding its presence in the SCS.

Diplomatic Sidestepping

Nevertheless, the PRC has consistently forestalled negotiations, thus incentivising littoral states to employ hard power to safeguard their interests. In 2012, the PRC insisted negotiations should not entail “one side imposing its views onto the other”.[28] This ran contrary to ASEAN’s 2008 Charter, which calls for “enhanced consultation” before meeting the PRC on the grounds that not all members were claimants.[29] The impasse was only cleared when ASEAN dropped the offending clause. However, the PRC reversed its position in the same year, declaring that the time for talks was “not ripe”, as Vietnam and the Philippines had violated the DoC repeatedly.[30] To date, only the guidelines expediting the creation of the CoC have been agreed upon.[31]

Alexander Wendt has noted that the behaviour of state actors “changes based on what certain events mean to them”.[32] As ASEAN’s political clout had been perceived to undermine the PRC’s vested interest (in unilaterally exploiting the SCS), the latter accepted ASEAN’s “centrality” in principle but rejected it in practice.[33] By turning down repeated rapprochement attempts, the PRC is ostensibly buying time to normalise the diplomatic backlash following the SEA states’ EEZ infringement. Ultimately, repeated naval deployments wear down a country’s resources and determination.[34]

ASEAN’s inability to reach a modus vivendi has compelled SEA states to undertake unilateral action against Chinese aggression. For example, the Philippines deliberately grounded the retired warship BRP Sierra Madre at the Second Thomas Shoal to assert sovereignty and stationed a garrison of Marines onboard.[35] Yet, their Rotation and Resupply (RORE) missions have been marred by deliberate collisions, water cannons, and laser harassment by the PRC.[36] The Philippines’ response has been calibrated to prevent these skirmishes from escalating and undermining bilateral economic interests.[37] However, should an armed attack occur, the U.S. is bound by the Mutual Defence Treaty to protect the Philippines.[38] Therefore, the calculus of a direct conflict between the U.S. and the PRC in the Indo-Pacific theatre is heightened significantly.

The Philippines deliberately grounded the retired warship BRP Sierra Madre at the Second Thomas Shoal to assert sovereignty and stationed a garrison of Marines onboard.

Deterring A Conflict

Even so, the increased U.S. regional engagement provides a bulwark against the PRC’s aggression, reducing the prospect of conflict. Following Obama’s “Pacific Pivot”, the U.S. military has enhanced military cooperation with regional allies and bolstered the number of troops and strategic assets based permanently and rotated in the region.[39] This sends a strong political signal that its interests dovetail with those of SEA states, deterring the PRC from upping the ante recklessly.

The U.S. has spearheaded multilateral military exercises, enhancing military interoperability among its partners. The ASEAN-U.S. Maritime Exercise (AUMX) aims to engender a “shared commitment to the region’s security, peace and stability”.[41] The “Balikatan” exercise was recently conducted with the Philippines in their EEZ for the first time. Soldiers from both armies practised sinking warships and “retaking” islands.[42] Beyond a deterrent message, these military exercises create an “us versus them” dichotomy, exemplifying the unity of the U.S.-led alliance vis-à-vis an isolated PRC. The confidence that the U.S. is “able and willing to protect” provides SEA states with geopolitical leverage when engaging the PRC.[43]

More significantly, U.S.-led alliances have fostered deeper bilateral ties between partners, strengthening their resolve to limit the PRC’s adventurism in the SCS. While embroiled in a separate maritime dispute with the PRC, Japan recognised the need for SEA states to safeguard their EEZs and donated retired Coast Guard ships to the Philippines and Vietnam in 2015 and 2016, respectively.[44] It also forged a trilateral alliance with the Philippines and U.S., paving the way for the cross-deployment of troops and economic partnerships.[45] Conflating diplomatic networks across the military-economic domains makes it increasingly difficult for the PRC to expand its regional influence.[46], [47] This creates a negative feedback loop: an increasingly aggressive PRC provides the impetus for SEA states to forge closer partnerships with the U.S., eroding the PRC’s balance of power in the region.

PRC Economic Engagement

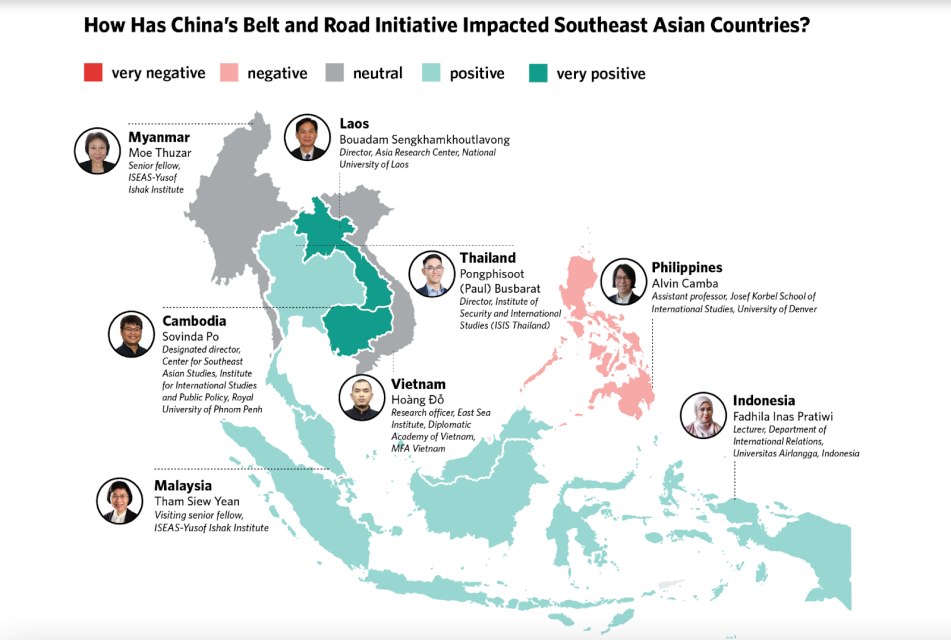

Amidst the US diplomatic “charm offensive”, the PRC-initiated geo-economic outreach has undermined ASEAN unity. Without proper governance of international norms, the claimants have the potential to backslide into the rule of the jungle. Established in 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) aims to connect the PRC with Europe, Asia, and Africa through a labyrinth of overland infrastructure and maritime routes.[48] The economic growth experienced by recipient states reinforces positive sentiments towards China. This quid pro quo prevents the PRC from being sidelined due to its aggression in the SCS.[49]

Economic globalisation increases interdependence between states. However, “when […] asymmetry exists, interdependence can become a weapon used in strategic competition”.[51] The over-dependence of some member states on the PRC is ASEAN’s Achilles heel. During the 45th ASEAN Ministerial Summit, Cambodia was accused of acting at Beijing’s behest when it disallowed the concerns arising from the SCS dispute to be reflected in the concluding statement.[52] For the first time in 45 years, ASEAN failed to issue a final communique.[53]

International relations are not merely “the interactions between state structures but the people behind them, who will form national characters that further influence state policies”.[54] As policymakers from Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia have developed a favourable view towards the PRC, a flywheel effect has been established.[55] The continued provision of economic aid enables the PRC to arm-twist recipient states into adopting a favourable foreign policy stance. This inherent difference in viewpoints becomes a liability as not everyone strives towards the same goal of stymieing PRC’s expansionism. The SCS dispute will inevitably morph into separate bilateral disputes without a collective effort to rein in the PRC. Every dispute that escalates has the potential to upend the regional security architecture, underscoring the ominous threat of a geopolitical timebomb.

Materialism and Idealism

Alexander Wendt observed a continuum between materialism and idealism in international relations.[56] Unlike a materialistic society where natural resources and geography shape interests and discourse, idealism favours “social identity and structure”. As “history and ideology seem to collide on a daily basis” in the Indo-Pacific, many commentariats believe ideational factors are the “most compelling driver of politics”.[57] However, there seems to be a symbiotic relationship between these two concepts. The reclamation of “historic space” provides the geo-economic resources for the PRC to become a global superpower and concurrently an integral part of its nationalist narrative.

As “history and ideology seem to collide on a daily basis” in the Indo-Pacific, many commentariats believe ideational factors are the “most compelling driver of politics”.

Overcoming the SCS imbroglio begets a chicken-and-egg conundrum, making the regional security architecture dynamic. It seems that diplomatic impasses and economic imperialism are characteristics of the new Chinese diplomatic paradigm. While the prospect of an all-out war in the SCS is low, the increasingly frequent use of “grey zone” tactics makes the state of affairs in the Indo-Pacific like a dormant volcano. Without clear conventions governing the rule of engagement for “grey” zone tactics, the current state of affairs can quickly spiral out of control.

Chow Xin Jie Nathan graduated with Distinction from Nanyang Junior College and the National University of Singapore Higher 3 (NUS H3) Programme, Geopolitics: Geographies of War & Peace. Offered to outstanding Pre-University history and geography students, the NUS H3 Programme provides greater academic depth and rigour of a first year university module. His research interests include the South China Sea territorial dispute, Hydropolitics and the US-China Power Rivalry. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of Nanyang Junior College and the National University of Singapore.

[1] Rachel Deason, “A Brief History of China: Xia Dynasty,” Culture Trip, November 08, 2017,

https://theculturetrip.com/asia/china/articles/a-brief-history-of-china-xia-dynasty/.

[2] La Trobe Asia, King’s College London and Griffith Asia Institute, “China’s Nine-dash Line proves stranger than fiction,” The Lowy Institute, April 12, 2022, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/china-s-nine-dash-line-proves-stranger-fiction.

[3] “United Nations Convention on The Law of The Sea,” United Nations, April 30, 1982, https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf.

[4] “The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China),” Permanent Court of Arbitration, January 22, 2013, https://pca-cpa.org/en/cases/7/.

[5] Hannah Beech, “Just Where Exactly Did China Get the South China Sea Nine-Dash Line From?,” Time, July 19, 2016, https://time.com/4412191/nine-dash-line-9-south-china-sea/.

[6] Center for Preventive Action, “Territorial Disputes in the South China Sea,” Council of Foreign Relations, March 19, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/territorial-disputes-south-china-sea.

[7] “What is the South China Sea dispute?,” BBC News, July 07, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-13748349.

[8] Shuxian Luo and Jonathan G. Panter, “China’s Maritime Militia and Fishing Fleets: A Primer for Operational Staffs and Tactical Leaders,” Army University Press, February 2021, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/January-February-2021/Panter-Maritime-Militia/.

[9] Lauren Butowsky, “South China Sea Dispute Reaches United Nations,” Yale University, June 30, 2014, https://archive-yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/south-china-sea-dispute-reaches-united-nations.

[10] Adam Taylor, “The $1 billion Chinese oil rig that has Vietnam in flames”, The Washington Post, May 14, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2014/05/14/the-1-billion-chinese-oil-rig-that-has-vietnam-in-flames/.

[11] Charlie Zhu, “China tests troubled waters with $1 billion rig for South China Sea,” Reuters, June 21, 2012, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-southchinasea-idUSBRE85K03Y20120621/.

[12] Michael Green, Kathleen Hicks, Zack Cooper, John Schaus and Jake Douglas, “Counter-coercion Series: Chinese-Vietnam Oil Rig Standoff,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, June 12, 2017, https://amti.csis.org/counter-co-oil-rig-standoff/.

[13] James R. Holmes, “The Return of China’s Small-Stick Diplomacy in South China Sea,” The Diplomat, January 09, 2014, https://thediplomat.com/2014/01/the-return-of-chinas-small-stick-diplomacy-in-south-china-sea/.

[14] Mikael Weissmann, “Chinese Foreign Policy in a Global Perspective: A Responsible Reformer Striving For Achievement,” Journal of China and International Relations, May 29, 2015, https://journals.aau.dk/index.php/jcir/article/view/1150.

[15] Ramses Amer, “China-Vietnam Drilling Rig Incident: Reflections and Implications,” Institute for Security and Development Policy, August 19, 2014, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/185075/2014-amer-china-vietnam-drilling-rig-incident.pdf.

[16] James Pearson and Khanh Vu, “Vietnam, China embroiled in South China Sea standoff,” Reuters, July 17, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKCN1UC0M4/.

[17] Abigail Ng, “South China Sea issues not easy to resolve, code of conduct negotiations will take time: PM Lee,” Channel News Asia, March 05, 2024, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/pm-lee-south-china-sea-cptpp-australia-visit-4171671.[18] “The ASEAN Charter,” ASEAN, January 2008, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/images/archive/publications/ASEAN-Charter.pdf.

[19] “Significance of the ASEAN Charter,” ASEAN, December 15, 2008, https://asean.org/asean-charter/.

[20] “Timeline for ASEAN-China Code of Conduct,” The Lowy Institute, n.d.,

https://interactives.lowyinstitute.org/charts/scs-challenge/timeline/.

[21] Leticia Simões, “The Role of ASEAN in the South China Sea Disputes”, E-International Relations, June 23, 2022, https://www.e-ir.info/2022/06/23/the-role-of-asean-in-the-south-china-sea-disputes/#google_vignette.

[22] Amitav Acharya, Will Asia’s Past Be Its Future? (International Security 28, no. 3), 150.

[23] Dang Cam Tu, “Perspectives: Greater Role for Smaller States in the Rules-Based Order,” Asia Link, February 25, 2021, https://asialink.unimelb.edu.au/stories/perspectives-greater-role-for-smaller-states-in-the-rules-based-order.

[24] Gudrun Wacker “Europe and the Indo-Pacific: Comparing France, Germany and the Netherlands,” Real Instituto Elcano, March 21, 2019, https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/en/analyses/europe-and-the-indo-pacific-comparing-france-germany-and-the-netherlands/.

[25] John Victor D. Ordoñez, “Netherlands to send warship to patrol South China with Philippines next year”, Business World, October 30, 2023, https://www.bworldonline.com/the-nation/2023/10/30/554551/netherlands-to-send-warship-to-patrol-south-china-with-philippines-next-year/.

[26] Chhengpor Aun, “Germany walks the talk on Southeast Asia”, East Asia Forum, April 15, 2024, https://eastasiaforum.org/2024/04/15/germany-walks-the-talk-on-southeast-asia/.

[27] Blake Herzinger, “Germany nervously tests the Indo-Pacific waters”, Foreign Policy, January 3, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/01/03/german-navy-indo-pacific-frigate-china-policy/.

[28] “Vice Foreign Minister of PRC Fu Ying’s interview with the Straits Times and Lianhe Zaobao,” PRC Embassy of Singapore, n.d., http://sg.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/sgsd/201209/t20120910_1715001.htm.

[29] Merriden Varrall, “ASEAN’s Way to Sustainable Development,” Disruptive Asia, n.d., https://disruptiveasia.asiasociety.org/aseans-way-to-sustainable-development.

[30] “ASEAN talks fail over South China Sea dispute,” aljazerra.com, July 13, 2012, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2012/7/13/asean-talks-fail-over-south-china-sea-dispute.

[31] Prashanth Parameswaran, “What’s Behind the New China-ASEAN South China Sea Code of Conduct Talk Guidelines?,” Wilson Centre, July 25, 2023, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/whats-behind-new-china-asean-south-china-sea-code-conduct-talk-guidelines.

[32] Alexander Wendt, Social Theory of International Politics (New York: Cambridge University Press), 112.

[33] Robert Beckman and Vu Hai Dang, Peaceful Maritime Engagement in East Asia and the Pacific Region (Brill |Nijhoff), 341-358.

[34] Bryan Clark and Jesse Sloman, “Deploying Beyond Their Means: America’s Navy and Marines at Tipping Point,” Centre for Strategic and Budgetary Assessment, n.d., https://csbaonline.org/uploads/documents/CSBA6174_(Deploying_Beyond_Their_Means)Final2-web.pdf.

[35] Jon Hoppe, “The Measure of the Sierra Madre,” Naval History Magazine Volume 36, Number 1, February 2022, https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2022/february/measure-sierra-madre.

[36] Bea Cupin, “China causes ‘heavy damage’ on Philippine resupply ship in Ayungin Shoal – AFP,” rappler, 24 March 2024, https://www.rappler.com/philippines/china-water-cannon-ayungin-shoal-march-23-2024/#:~:text=Philippines%2DChina%20relations-,China%20causes%20%27heavy%20damage%27%20on%20Philippine%20resupply,ship%20in%20Ayungin%20Shoal%20%E2%80%93%20AFP&text=WATER%20CANNON.

[37] Jim Gomez, “Philippines lodges its ‘strongest protest’ against China over a water cannon assault in disputed sea,” apnews, March 25, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/south-china-sea-philippines-shoal-f789f10b3a47ee0d22e8dec59df57eb2#.

[38] Karen Lema, “US issues guidelines on defending Philippines from South China Sea attack,” Reuters, May 04, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/us-issues-guidelines-defending-philippines-south-china-sea-attack-2023-05-04/.

[39] Jim Garamone, “US Official Says Allies Acting Together to Deter China,” US Department of Defense, September 29, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3543179/us-official-says-allies-acting-together-to-deter-china/.

[40] Alan Robles and Dewey Sim, “In a US-China war, whose side is Southeast Asia on? Philippines, Singapore and Malaysia ponder the unthinkable,” South China Morning Post, September 19, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3101977/us-china-war-whose-side-southeast-asia-philippines-singapore-and.

[41] “First ASEAN-US Maritime Exercise Successfully Concludes,” Commander, Logistics Group Western Pacific Public Affairs Office, September 06, 2019, https://www.c7f.navy.mil/Media/News/Display/Article/1954403/first-asean-us-maritime-exercise-successfully-concludes/.

[42] Helen Davidson, “China sounds warning after Philippines and US announce most expansive military drills yet,” The Guardian, April 18, 2024.

[43] Hugh White, “Explaining China’s Behaviour in the East and South China Sea,” The Interpreter, May 22, 2014, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/explaining-china-s-behaviour-east-south-china-seas.

[44] Kentaro Furuya, “Japan Coast Guard’s rising role in a rules-based Indo-Pacific,” asiatimes, January 14, 2023, https://asiatimes.com/2023/01/japan-coast-guards-rising-role-in-a-rules-based-indo-pacific/#:~:text=Tokyo%20subsequently%20donated%20patrol%20ships,and%20advance%20Tokyo%27s%20FOIP%20concept.

[45] Richard Heydarian, “Emerging U.S.-Japan-Philippine alliance is making waves in Asia,” Nikkei Asia, April 18, 2024, https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Emerging-U.S.-Japan-Philippine-alliance-is-making-waves-in-Asia.

[46] Michael Lim, “PH-US-Japan triad: An alliance of ‘equals’?,” The Star, April 21, 2024, https://www.thestar.com.my/news/focus/2024/04/21/ph-us-japan-triad-an-alliance-of-equals.

[47] Tarun Chhabra, Rush Doshi, Ryan Hass and Emilie Kimball, “Global China: Regional influence and Strategy,” Brookings, July 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/global-china-regional-influence-and-strategy/.

[48] Tessa Wong, “Belt and Road Initiative: Is China’s trillion-dollar gamble worth it?,” BBC News, October 17, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-67120726.

[49] China Power, “How Is the Belt and Road Initiative Advancing China’s Interests?,” Centre for Strategic and International Studies, n.d., https://chinapower.csis.org/china-belt-and-road-initiative/.

[50] Ongphisoot Busbarat, Alvin Camba, Fadhila Inas Pratiwi, Sovinda Po, Hoang Do, Bouadam Sengkhamkhoutlavong, Tham Siew Yean and Moe Thuzar, “How Has China’s Belt and Road Initiative Impacted Southeast Asian Countries?,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, December 05, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/12/05/how-has-china-s-belt-and-road-initiative-impacted-southeast-asian-countries-pub-91170.

[51] Joseph S. Nye Jr, Power and Interdependence with China (The Washington Quarterly), 43.

[52] Ernest Z. Bower, “China Reveals Its Hand on ASEAN in Phnom Penh,” Centre for Strategic and International Studies, July 20, 2012, https://www.csis.org/analysis/china-reveals-its-hand-asean-phnom-penh.

[53] Erlinda F. Basilio, “Why there was no ASEAN joint communiqué,” Official Gazette of the Government of the Philippines, July 18, 2012, https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2012/07/18/why-there-was-no-asean-joint-communique/.

[54] William Bloom, Personal Identity, National Identity, and International Relations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

[55] Johanna Son, “Laos and Cambodia: The China Dance,” Reporting Asean, September 29, 2016, https://www.reportingasean.net/laos-cambodia-china-dance/.

[56] Alexander Wendt, Social Theory of International Politics, (Cambridge University Press), 22-44, 92-190, 246-312.

[57] Ryan Kueh, Two Birds with One Stone: Natural Gas and Eurasian Regionalism (Southern California International Review Volume 12, Number 1).