Abstract: The progressive integration of artificial intelligence (AI) transforms military command across doctrinal, procedural, and cultural dimensions. AI reshapes the balance between centralisation and decentralisation across command levels. Using Col. John Boyd’s OODA Loop as a generic model of the military decision-making process (MDMP), it is possible to see how AI influences each step of decision-making—from information gathering to tactical execution—and assesses its implications for Mission Command (MC) as a decentralised leadership philosophy. Western militaries, with their longstanding tradition of decentralised decision-making, may be particularly well-positioned to harness AI as a tool of empowerment rather than surveillance.

Problem statement: How does integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) affect the Military Decision-Making Process (MDMP) and Mission Command?

So what?: Effective integration of AI into MDMP, to enhance rather than undermine Mission Command, will help commanders deliberately vary between centralised and decentralised approaches to maximise the accuracy and speed of decisions.

Source: shutterstock.com/Shutterstock AI Generator

Introduction

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into military operations challenges traditional models of command and control (C2) as well as Military Decision-Making Processes (MDMP). Worldwide, militaries increasingly rely on AI to enhance operations’ speed, precision, and coherence across domains.

However, this technological shift also confronts core leadership philosophies in Western forces, where Mission Command is central. Here, Mission Command is a leadership style and doctrinal principle rooted in decentralisation and subordinate initiative. As AI systems generate unprecedented access to data, senior commanders must reconsider how they distribute authority, interpret situational complexity, and maintain trust across hierarchical levels.

Mission Command is a leadership style and doctrinal principle rooted in decentralisation and subordinate initiative.

To better understand the complexities of technological innovation regarding doctrine and culture, this paper uses John Boyd’s OODA Loop as a generic model of the MDMP—rather than in its historical or Air Force-specific context. In doing so, it continues James Johnson’s argument that integrating AI into military processes and structures at all levels may counterintuitively increase the importance of human decision makers.[1]

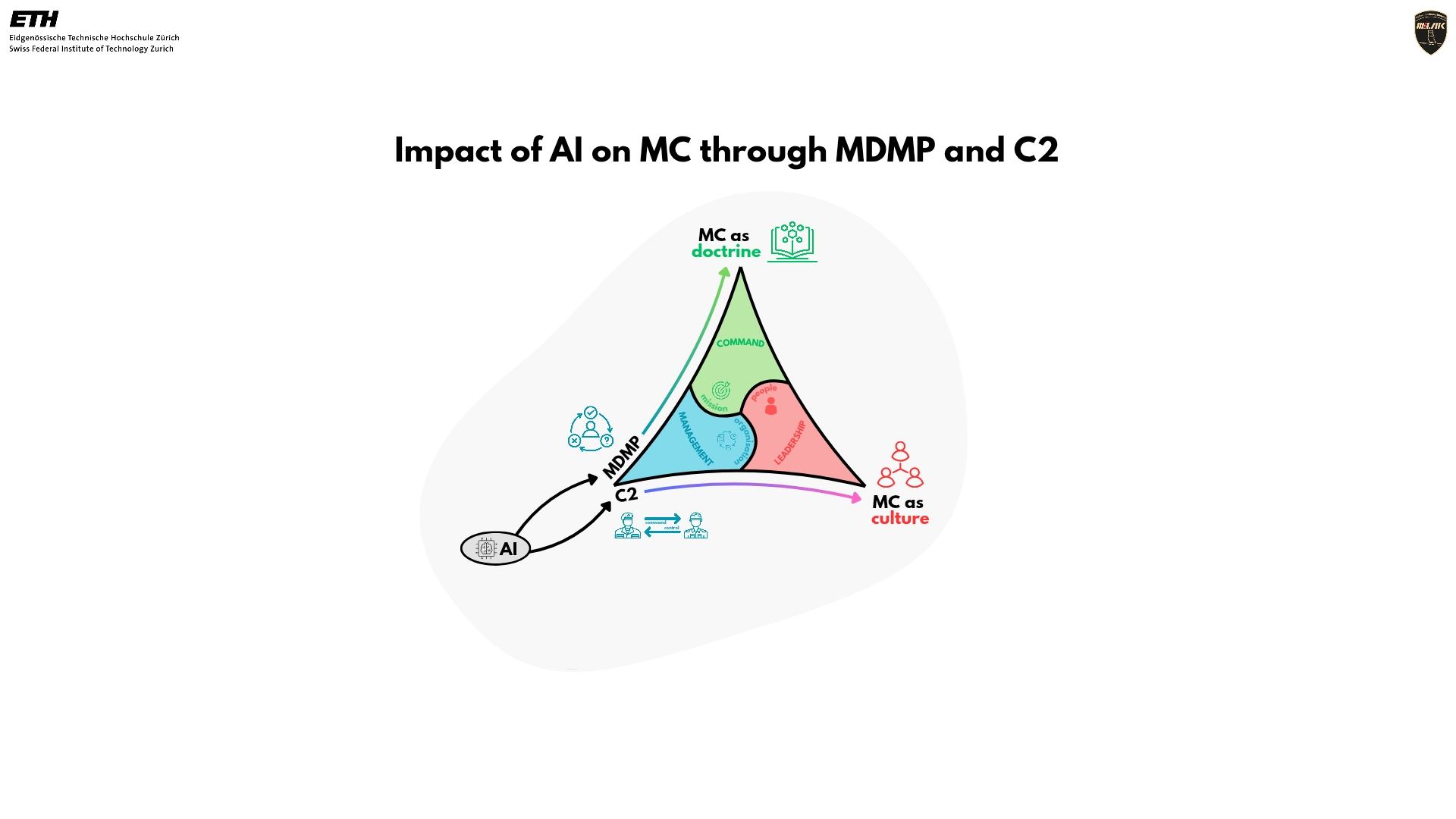

Mission Command in Doctrine, Culture, MDMP and C2

Mission Command as a leadership concept dates back to the Prussian military reforms of the 19th century.[2] Today, most Western militaries aspire to it.[3] Precise definitions differ in the various handbooks and regulations,[4], [5] but usually include decentralisation and empowerment of junior leaders. Ukraine’s response to the invasion by Russia, especially in its early months, underlines the advantages of such an approach: both domestic[6] and foreign[7] observers attributed the tactical superiority of the more agile Ukrainian military to their successful adoption of Mission Command. In contrast, Russia’s rigid “Detailed Command” approach is a counter-concept comprised of centralised, directive leadership.

NATO defines Mission Command as “a philosophy of command that advocates centralised, clear intent with decentralised execution; a style that describes the ‘what’, without necessarily prescribing the ‘how’.”[8] Various authors blur this principle by writing, i.e., “centralised planning and decentralised execution”[9] or “centralised control, decentralised execution”.[10] It seems that NATO’s definition provokes a top-down understanding of Mission Command, and that ultimately, only execution is delegated. Understood in this way, however, it is a rather empty concept, since even in the Russian understanding of command, execution is decentralised.

A consistent interpretation of Mission Command is therefore essential: emphasising that only the intent is centralised, thus allowing the subordinate to decide and act as autonomously as possible. Additional centralisations may reflect military culture, and arguably, this may be one of the main reasons armed forces struggle to adopt Mission Command successfully.[11] However, centralising more than the absolute minimum is at odds with the original understanding of Mission Command, the Prussian Auftragstaktik.[12]

The superiority of Auftragstaktik, as Mission Command usually refers to in its original German, was particularly evident in the Second World War. In his renowned study Kampfkraft,[13] Martin van Creveld explains why, despite the strategic superiority of the Allies, the Wehrmacht retained tactical superiority at lower levels until the war’s final phases. Col. John Boyd comes to similar conclusions in his lecture “Patterns of Conflict”,[14] in which he analysed the effect of Mission Command on the MDMP and C2. Such a procedural perspective is entirely consistent with the historical explanation that the Prussian generals developed Mission Command mainly because of the technological innovations of the 19th century: long distances and high speeds meant that centralised command of the battle was no longer feasible.[15]

Suppose the origins of Mission Command are at least partly due to technical innovations that have led to a divergence between the speed of military leadership and military action. In that case, one might ask how introducing new technologies since the end of the Cold War would have influenced Mission Command. This is particularly tempting for those who see Mission Command as a “necessary evil” at odds with coordinating efforts—such statements were already extant in the 1990s: “Mission Command will have died with the last non-digital company command.”[16] and have recently received renewed attention in the context of automation and Artificial Intelligence (AI).[17]

Given the advantages of Mission Command, however, some also address “The potential risk associated with this trend is the micromanagement of warfare at the expense of mission command.”[18]These and other authors firmly state that Mission Command should be retained.[19], [20] Nevertheless, the question remains whether Mission Command can and should survive.[21]

The potential risk associated with this trend is the micromanagement of warfare at the expense of mission command.

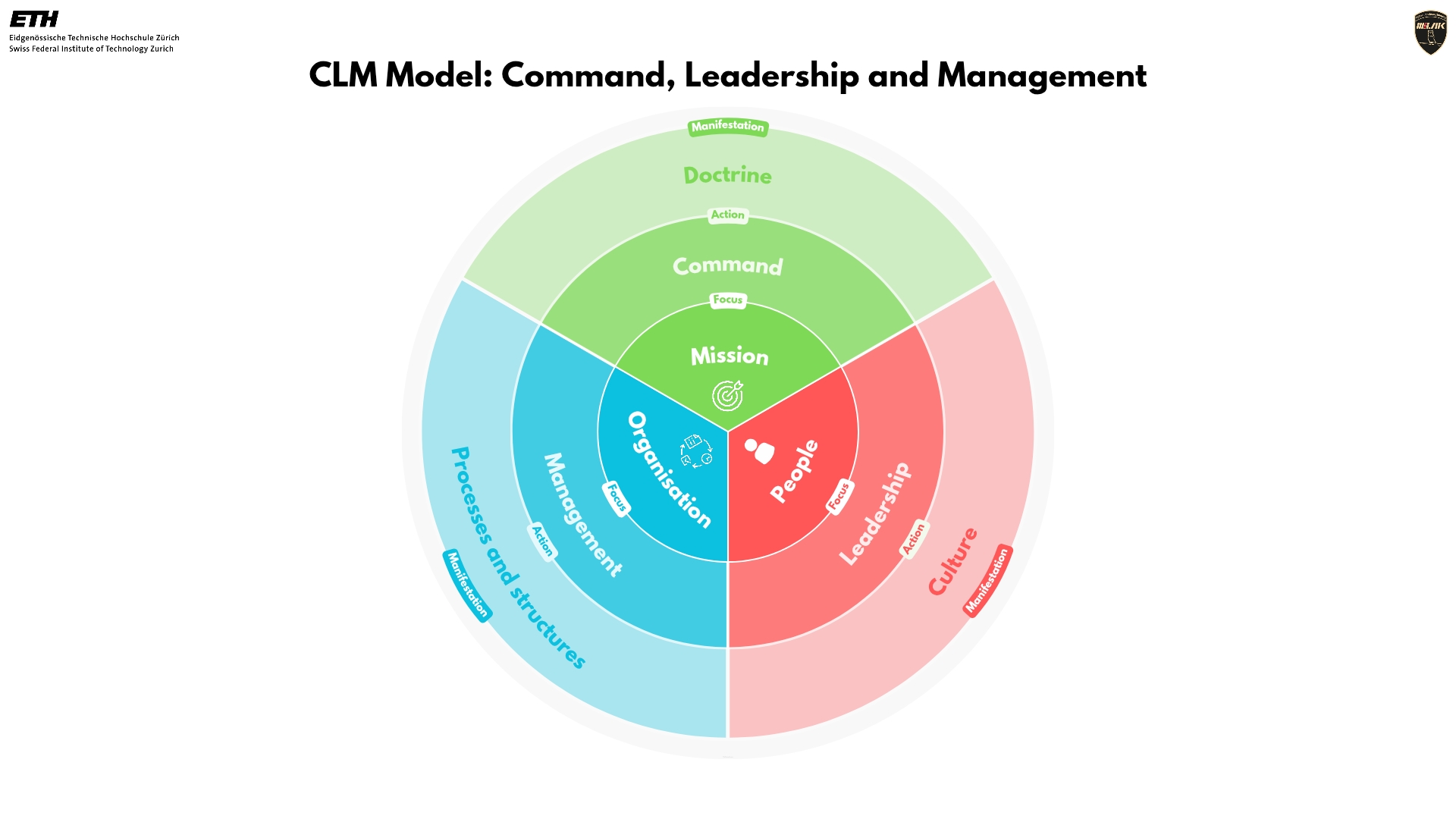

Military command should treat centralisation or decentralisation not as opposing choices but as ends of a spectrum along which command must adapt depending on the context and content of the mission. This requires a holistic understanding of Mission Command, which we approach through the Command-Leadership-Management framework.[22]

This approach goes back to Stephen Bungay[23] and was adopted as the British Army Leadership Doctrine,[24] sharpened in definition by Patrick Hofstetter[25] and officialised for the Swiss Armed Forces in 2025 with the “Strategie zur Vision 2030” of the Swiss Department of Defence.[26] A brief explanation will show how the Command-Leadership-Management (CLM) framework allows leaders to address the three essential aspects of Mission Command: first, its significance as military doctrine;[27] second, its cultural significance as a leadership philosophy;[28] and third, its procedural and structural significance through manifestation both in C2 and MDMP.[29] This holistic view helps to recognise, on the one hand, that this triadic model is sufficient and, on the other hand, that the three dimensions of Mission Command are interrelated and need to be analysed accordingly.

Source: Authors.

The model defines the following: command is mission-centric, leadership is people-centric, and management is organisation-centric. These aspects manifest in different areas of an organisation:

- Command, i.e., how the mission is generally accomplished, manifests itself in the doctrine;

- Leadership, i.e., the way people are treated in general, is manifested in the culture;

- Management, i.e., how the organisation functions generally, is manifested in processes and structures.

Conceptually, Mission Command is not a doctrine in the sense of a standardised tactical, operational or strategic approach, such as manoeuvre, attrition or guerrilla warfare,[30] multidomain operations, or network-centric warfare.[31] Mission Command is a generic command doctrine that may accord more or less with any given warfighting doctrine.

When considering Mission Command culturally, looking at the prerequisites for its successful application is beneficial. The associated obstacles to implementation have been thoroughly examined[32] using Edgar H. Schein’s organisational culture model.[33] Yet the influence runs in both directions. If Mission Command empowers followers, this undoubtedly fosters their trust, self-confidence, and initiative–characteristics that, in turn, benefit the successful application of Mission Command. This culture cannot be built up in the hot state. Therefore, Donald E. Vandergriff suggests that “Mission Command must be integrated into all education and training from the very beginning of basic training”.[34]

When considering Mission Command culturally, looking at the prerequisites for its successful application is beneficial.

Just as Mission Command can obviously influence doctrine and culture, it does so on processes and structures. Here, as in the other domains, influence is mutual. However, Mission Command influences the processes rather than structures; ultimately, C2 structures are primarily political or strategic decisions and thus prerequisites for and not outcomes of Mission Command.

In terms of interdependencies, two things stand out. MDMPs are primarily related to doctrine, while C2 structures are related mainly to culture. The former is because decision-making processes are ultimately nothing more than generic forms of mission accomplishment, a procedural blueprint, so to speak, filled with doctrinal content. The latter follows from purely sociological considerations: those closer to each other within a given structure are more likely to influence each other. For example, if air defence is subordinate to ground forces, it will tend to align itself culturally with them through closer exchanges. If, on the other hand, it is part of the air force, it will also be part of the corresponding cultural area.

Source: Authors.

The MDMPs of the various armed forces differ in their national characteristics. However, a generic process is required for a general answer rather than a country-specific one. The generic process that Boyd described as the OODA (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act) Loop[35] serves this purpose, shedding light on the dependencies of Mission Command and the MDMP in general and not on a special national form. In the same sense, Boyd himself had used the OODA framework to explain the apparent superiority of the German Mission Command approach in the Second World War:[36]

- “The German concept of mission can be thought of as a contract, hence an agreement, between superior and subordinate. The subordinate agrees to make his actions serve his superior’s intent in terms of what is to be accomplished, while the superior agrees to give his subordinate wide freedom to exercise his imagination and initiative in terms of how intent is to be realised.”[37]

- “The secret of the German command and control system lies in what’s unstated or not communicated to one another—to exploit lower-level initiative yet realise higher-level intent, thereby diminish friction and reduce time, hence gain both quickness and security.”[38]

One of Boyd’s central statements is that successful warfare involves making one’s own OODA Loop turn faster than the opponent and, ideally, collapsing the opponent’s loop through speed, disruption, or deception. Long before Boyd, it was recognised that speed is crucial in warfare. Clausewitz, for example, explains under the term “coup d’œil” that it is “the quick recognition of a truth that the mind would ordinarily miss or would perceive only after long study and reflection” that distinguishes military genius.[39]

It is evident that AI can facilitate such swift recognition. Just as the technical advances of the 19th century had allowed for acceleration, the 21st century’s innovations are also reflected in the OODA Loop. The following section does this specifically for integrating AI into the MDMP or, more generally, into the OODA Loop. Therefore, we need to explain Boyd’s OODA Loop in more detail.

The Impact of AI on the MDMP

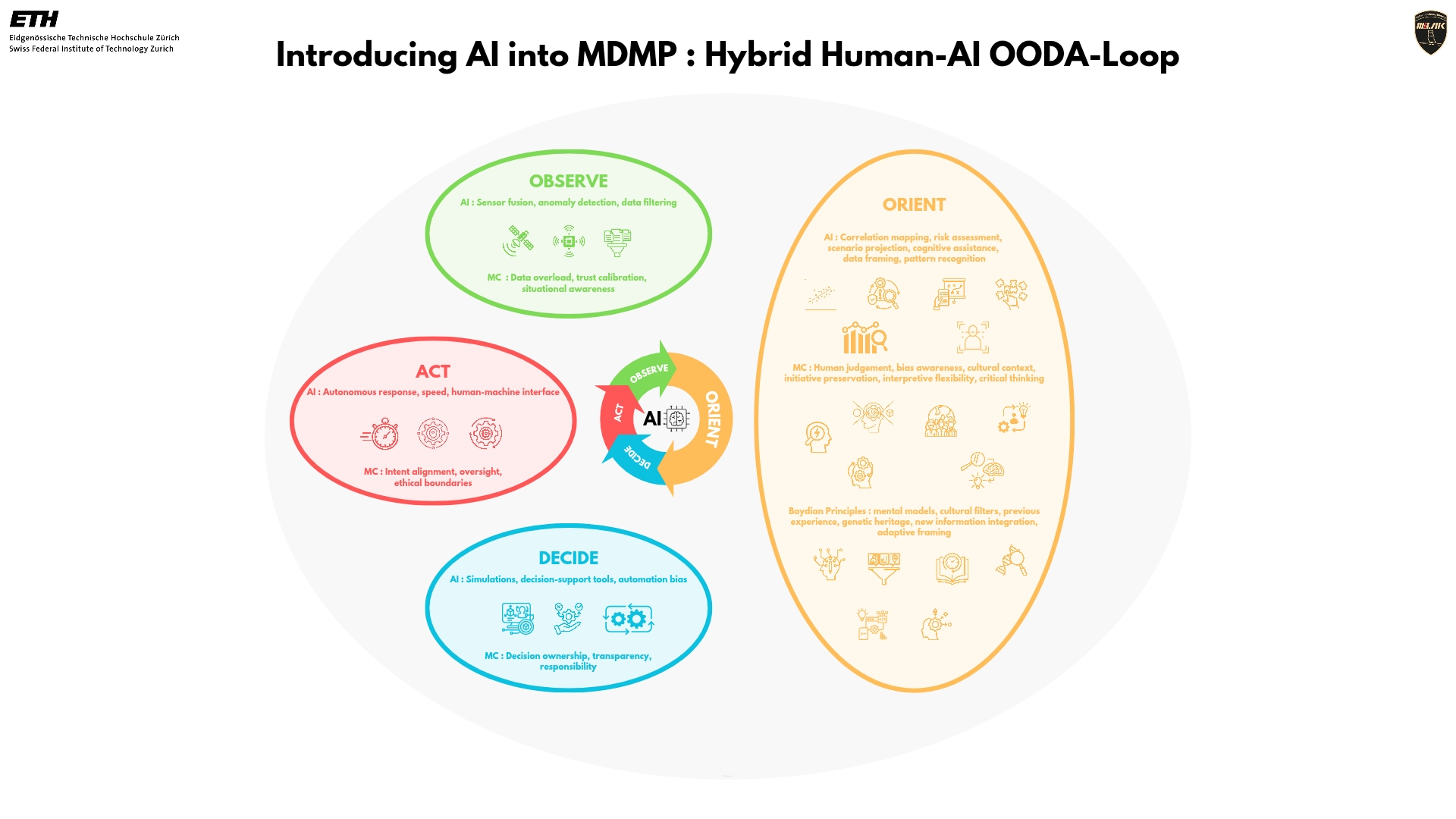

Initially developed by the US Air Force pilot and strategist Col. John Boyd to explain decision-making in aerial combat, many Western armies have since adopted the OODA Loop as a conceptual framework for adaptive decision-making in modern conflict.[40] Its abstraction allows for a conceptual discussion independent of national doctrine or force structure. Following Boyd’s core idea that military success derives from operating faster and more coherently through this loop than one’s adversary,[41] the subsequent section examines how AI influences each OODA Loop’s steps—and how this may fundamentally alter the structure and dynamics of MDMP in modern warfare.

The first step of the OODA Loop—observe—refers to collecting information from the operational environment. Sensors and digital systems generate an ever-increasing volume of data, shaping this step in contemporary conflicts. ISR (intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) systems, satellite imagery, drone feeds, and cyber intelligence generate an informational density far exceeding human operators’ processing capacity.[42] In contrast to the past, when timeliness or availability of information was the limiting factor, modern forces increasingly face the inverse problem: an abundance of raw data with limited capacity to convert it into actionable knowledge.

ISR systems, satellite imagery, drone feeds, and cyber intelligence generate an informational density far exceeding human operators’ processing capacity.

AI, especially machine learning and pattern recognition, helps mitigate data overload. It enables rapid real-time filtering, clustering, and prioritisation of data streams. Rather than relying solely on human analysis, AI-supported systems can autonomously detect anomalies, classify threats, and fuse diverse inputs into a coherent picture.[43] However, the accuracy of AI-supported observation depends on data quality and algorithmic design, which introduces new sources of uncertainty into the MDMP.

The specific application and reliability of AI-supported observation also depend on the command level at which it is employed. On the tactical level, AI is primarily used for real-time sensor data fusion, target recognition, and rapid threat classification in direct support of manoeuvre units. These systems operate under tight time constraints and are often embedded in platforms such as unmanned aerial vehicles or fire control systems.[44]

At the operational level, AI contributes to the coordination of multiple units, force allocation, and anticipating adversary movements through predictive modelling and operational wargaming. The data requirements here are broader, and the systems must synthesise inputs across different domains and formations.[45]

At the strategic level, AI is increasingly used in intelligence analysis, long-term scenario planning, and detecting emerging threats in the information and cyber domains. At this level, the focus shifts from speed to pattern recognition across geopolitical, economic, and military indicators.[46] Therefore, each level poses distinct challenges regarding data volume, reliability, and decision horizons. As a result, AI must be tailored to both technological and command-level contexts.

At the strategic level, AI is increasingly used in intelligence analysis, long-term scenario planning, and detecting emerging threats in the information and cyber domains.

The second step of the OODA Loop—orient—is central to Boyd’s theory. While observation provides data, orientation gives it meaning. Boyd described this step as synthesising cultural background, prior experience, training, and analytical reasoning.[47] Concerning mission command and AI, Johnson has emphasised that Boyd’s theory loses its core message if the orientation step is not understood as a priority.[48] It is thereby striking that Clausewitz’ ‘coup d’œil’ refers to orientation rather than to decision.

Orientation finally shapes the interpretation of information and leads to the implication of acting options. AI contributes to this process not only by analysing data but also by structuring and presenting data. In modern command systems, AI tools support commanders by highlighting correlations, assessing risks, and suggesting probable developments.[49] However, these outputs rely on algorithmic models trained on historical data and defined parameters. If not carefully integrated, such systems may promote a narrow interpretation of the situation and reduce the diversity of considerable options.

Therefore, junior and senior leaders must understand that AI supports human judgment, not replaces it. In Mission Command, where initiative and independent decision-making are essential, commanders must remain able to question or override AI-generated suggestions when necessary.

The third step of the OODA Loop—decide—refers to selecting a course of action based on the processed and interpreted information. Traditionally, this step rests on the commander’s experience, situational awareness, and operational intent. With the integration of AI, this decision-making process is increasingly supported by AI tools such as simulations, analytics, and wargaming systems.[50], [51]

These tools offer clear benefits. They can assess a broader range of scenarios in shorter timeframes, quantify risks, and visualise probable outcomes. Especially in time-critical or complex situations, such systems can help reduce cognitive load and improve decision speed. However, they also raise the question of decision delegation to followers. As confidence in AI systems increases, junior-level tactical leaders will likely show a tendency to follow AI’s recommendations without further scrutiny—especially under time pressure.

This dynamic blurs the boundary between decision support and decision automation. Studies have shown that operators often follow algorithmic recommendations without critical review in high-pressure environments—a phenomenon called automation bias.[52], [53] While partial automation may be technically feasible, strategic analysts stress the continued necessity of human oversight, particularly in contexts where legal responsibility and operational ethics are involved.[54] Within the framework of Mission Command, decisions must remain comprehensible, transparent, and attributable—both to the commander, who bears ultimate responsibility, and to the subordinate, whose trust is essential. For the commander, transparency ensures accountability and enables effective leadership. For the subordinate, it fosters trust; black-box systems offer little foundation for the initiative and confidence that Mission Command demands. The challenge lies in maintaining human authority over machine-generated options, even when these appear more efficient or statistically plausible.

While partial automation may be technically feasible, strategic analysts stress the continued necessity of human oversight, particularly in contexts where legal responsibility and operational ethics are involved.

The fourth step of the OODA Loop—act—refers to executing the course of action. Traditional operation understanding links this step to command hierarchies, communication and force deployment. However, this step undergoes substantial transformation with the increasing use of autonomous and semi-autonomous systems. Unmanned platforms, loitering munitions, and algorithmically controlled defensive systems can respond faster than humans, especially in contested environments.[55]

Technically, integrating AI into tactical execution—acting at the lowest command level—offers significant advantages. Autonomous systems can respond within milliseconds, operate in denied environments, and execute complex manoeuvres based on predefined parameters. However, these capabilities come at a cost. When systems have greater operational freedom, it raises concerns about accountability, ROE, and adaptability.[56] Operational misalignment between human intent and machine execution, caused by misunderstood commands or unforeseen environmental variables, is a risk.[57]

These concerns do not imply that human decision-making or action is fundamentally better than AI or automatic weapons. People make mistakes—both consciously and unconsciously. They break laws, whether self-imposed or externally mandated, and violate moral standards, whether personal or universal. Misalignment is not just a human/machine problem; it is first and foremost a human/human problem. However, people are more willing to accept mistakes made by others than those made by machines. It may be irrational, but the public rejects robot taxis as soon as they hit a child—even if the robot’s probability of error is significantly lower than that of an average human driver.[58]

However, the desire for attribution and accountability is not just an intuitive need of the population. Ultimately, it is a demand of the enlightenment on state action: humans shall be protected from the arbitrariness of the executive branch, and the judiciary should correct possible mistakes to restore justice. A fallible commander can be convicted and punished, but a fallible robot cannot. Even if this demand for accountability stems from emotion or intuition rather than rationality, it remains valid on legal-philosophical grounds.[59]

In Mission Command, the act step must retain a degree of human oversight. While certain functions may be delegated for speed and efficiency, the overall framework must ensure that action remains guided by intent, not merely by code. This includes mechanisms for intervention, abort criteria, and a clear delineation of human versus machine authority within the execution chain.

It is true that potential antagonists may not share the same concerns about legal or ethical constraints. However, this is not a new problem: military ethics and international humanitarian law have long grappled with the challenges of dealing with an opponent who disregards such norms. The Geneva Conventions agree that disregard by the opponent does not release us from our obligations.[60] The question appears to be more complex from a military ethics perspective, as considerations regarding reprisals demonstrate.[61] At the same time, however, it would be tantamount to abandoning our own ethical standards if we were to reject them because our opponents adhere to different standards. Our commitment to these principles is not contingent on reciprocity, but on upholding the values we claim to defend.

Military ethics and international humanitarian law have long grappled with the challenges of dealing with an opponent who disregards such norms.

Integrating AI into the OODA Loop presents both a logical evolution and a fundamental shift in military decision-making. Across all four steps—observation, orientation, decision, and action—AI systems offer the potential to increase speed, reduce cognitive burden, and manage complexity beyond human capability. In doing so, they support Boyd’s overarching goal: to operate inside the adversary’s decision cycle and gain tactical and operational advantage.[62], [63]

Source: Authors.

From a Mission Command perspective, the challenge is not to prevent the use of AI but to ensure its integration respects the underlying principles of decentralised, intent-driven leadership. Whether artificial intelligence ultimately leads to greater centralisation or decentralisation in MDMP and Mission Command depends on how its capabilities are operationalised.

Centralisation and Decentralisation: From Opposition To Continuum

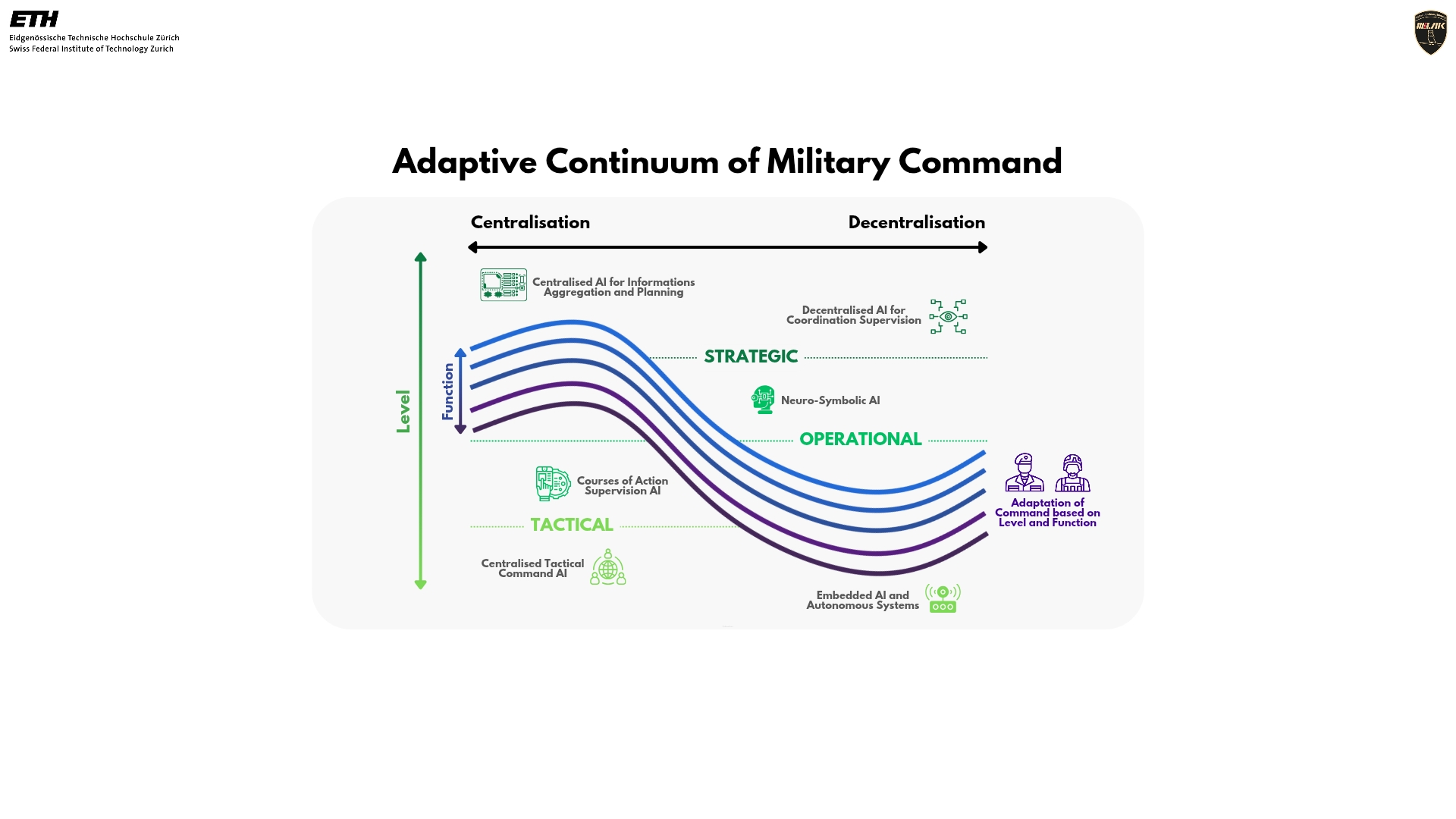

Military leaders can no longer conceptualise command in the age of AI through the binary lens of centralisation versus decentralisation. Instead, command constitutes an adaptive continuum, within which militaries must reorganise themselves in real time according to the operational context. Technological advancements sometimes promote centralised command and, at other times, foster greater autonomy at junior levels. For example, access to an “omniscient operational picture” enabled by AI may tempt senior leadership to micromanage every tactical action from a centralised decision-making hub. In addition, potential cyberattacks and the complexity of the electromagnetic spectrum suggest that AI may be more effectively employed to enhance decentralised initiative at the tactical edge.[64] Centralisation and decentralisation should thus be understood not as mutually exclusive choices but as two poles of a single dynamic that must be modulated.

Western militaries constantly navigate this centralisation-decentralisation continuum, adjusting their posture based on operational requirements. Recent operational feedback confirms the importance of such flexibility. This dialectic is not new; it continues the tradition of Mission Command, which advocates for centralised intent and decentralised execution. It may be assessed through a framework measuring the influence and weight of mission-related, human and organisational factors. In the case of Western armed forces, this distribution implies that the only viable approach to centralisation and decentralisation is the one broadly aligned with NATO’s Mission Command model. AI does not undermine this foundation but rather intensifies its internal tensions: it enables near-omniscient centralised control and local-level automated decision-making.[65]

A truly fluid and agile comprehension of command must be capable of adapting the degree of centralisation according to the hierarchical level and the command function being exercised. At the strategic and operational levels, a certain degree of centralisation remains essential to maintain a shared vision and unity of effort. At these echelons, we already observe the integration of robust centralised AI systems—such as Large Language Models (LLMs)—for intelligence aggregation and campaign planning support.[66] These strategic AI tools can process vast volumes of data and generate global options, contributing to a form of “hybrid human-machine judgment” at the upper tiers of command.[67]

Nevertheless, even at these levels, commanders must retain doctrinal flexibility to adapt their leadership style. Complex battlefields may call for temporary recentering of control (e.g., to coordinate a multidomain operation), followed by a re-delegation of authority to subordinate echelons as the situation evolves and demands increased initiative.

Complex battlefields may call for temporary recentering of control, followed by a re-delegation of authority to subordinate echelons as the situation evolves and demands increased initiative.

At the tactical level, however, the decentralised initiative becomes paramount in responding to the real-time chaos of combat. Here, embedded AI (Edge AI) and autonomous systems will play a decisive role. Intelligent sensors, onboard Bayesian algorithms, and lightweight decision-support systems will provide frontline units with immediate analysis and action capabilities independent of higher-level directives. This reinforces the concept of an augmented OODA Loop—where the Observe and especially the Orient steps are accelerated by AI—while the Decide and Act steps can be executed locally in an informed manner, remaining aligned with the overarching commander’s intent. Such integration enables small units to complete the decision cycle faster than the adversary, thereby contributing to the decision superiority sought in contemporary military doctrines.[68]

In this conceptualisation, in which AI assistance enhances human performance, the continuing adaptation of military command between centralisation and decentralisation emerges as a critical pathway in digital evolution. Decentralised autonomy at lower echelons does not imply the absence of control: command retains visibility through a continuous information flow, only intervening when necessary or reorienting efforts according to strategic objectives. All these considerations lead to this adaptive continuum of military command.

Source: Authors.

Simultaneously, each domain of the CLM model—Command, Leadership, and Management—benefits differently from this AI-enabled adaptability. Command gains from centralised AI tools, which support strategic orientation and ensure clear communication of intent. Tactical AI is profoundly transforming leadership: the field commander is now equipped with unprecedented local decision-support tools—such as those illustrated in the augmented OODA Loop—allowing for semi-autonomous action that remains tightly coupled to the overarching strategic direction. Lastly, Management can leverage analytical AI systems to optimise logistics, which tends to favour centralisation; yet, it can also delegate certain decisions to lower levels via self-organising tools (e.g., models such as Gallatin that dynamically allocate resupply based on real-time frontline needs.)[69]

Tactical AI is profoundly transforming leadership.

In this way, AI functions as a differentiated catalyst: centralising for command when synthesising a global vision, empowering leadership at the lowest levels by accelerating execution, and rationalising for management by enabling cross-functional optimisation.

From a more critical perspective, this fluid transition between centralisation and decentralisation—while ideal in theory—collides with entrenched structural, doctrinal, and cultural forces within military organisations. On the one hand, Western armed forces are steeped in the philosophy of Mission Command and the principle of subsidiarity, which emphasise delegation and subordinate initiative. These principles represent a significant doctrinal legacy born from the necessity to act despite uncertainty and battlefield chaos. They assert that the leader must define a clear intent and then relinquish control over the means of execution, allowing capable followers to seize opportunities as they arise. This culture of trust and empowerment is a prerequisite for any effective decentralised approach.

On the other hand, the temptation toward centralisation resurfaces with every technological revolution. Today, hyper-connectivity, the massive availability of data and AI grant military headquarters a sense of global oversight that can lead to a tendency to recentralise decision-making authority. In times of peace or when facing diffuse threats, centralised control may appear logical to optimise coordination; “Centralised planning is a manifestation of a belief in the ability to optimise”.[70] This reflex, a legacy of the industrial age and likely reinforced by cognitive biases such as the illusion of control,[71] risks undermining the responsiveness required in real combat. It may run counter to the Mission Command philosophy cherished by Western militaries.

Centralised planning is a manifestation of a belief in the ability to optimise.

This tension reflects a latent conflict between technological architecture and organisational architecture. For instance, the French Army has observed that specific “centralising digital tools” and bureaucratic complexity can “slow down, paralyse, or discourage subordinate initiative”.[72] AI may either exacerbate this dysfunction—by reinforcing top-down, omnipresent control—or help remedy it by equipping subordinates with the means to act independently and with insight.

The key distinction lies in the adopted command culture. Western militaries, with their longstanding tradition of decentralised decision-making, may be particularly well-positioned to harness AI as a tool of empowerment rather than surveillance. Nevertheless, this requires sustained investment in training, education and doctrinal adaptation. The human factor—especially mutual trust between command echelons—remains central to this transformation. Learning to trust AI-generated recommendations will be crucial without succumbing to blind delegation or intrusive interference.

Similarly, military forces with less experience in subsidiarity can evolve: recent doctrinal reflections from Chinese military thinkers also advocate for greater flexibility and local initiative supported by emerging technologies.[73] This suggests that cultural determinism can be disrupted by operational realities and the opportunities AI presents.

From Binary to Multidimensional: Towards an Adaptive Model of Military Command

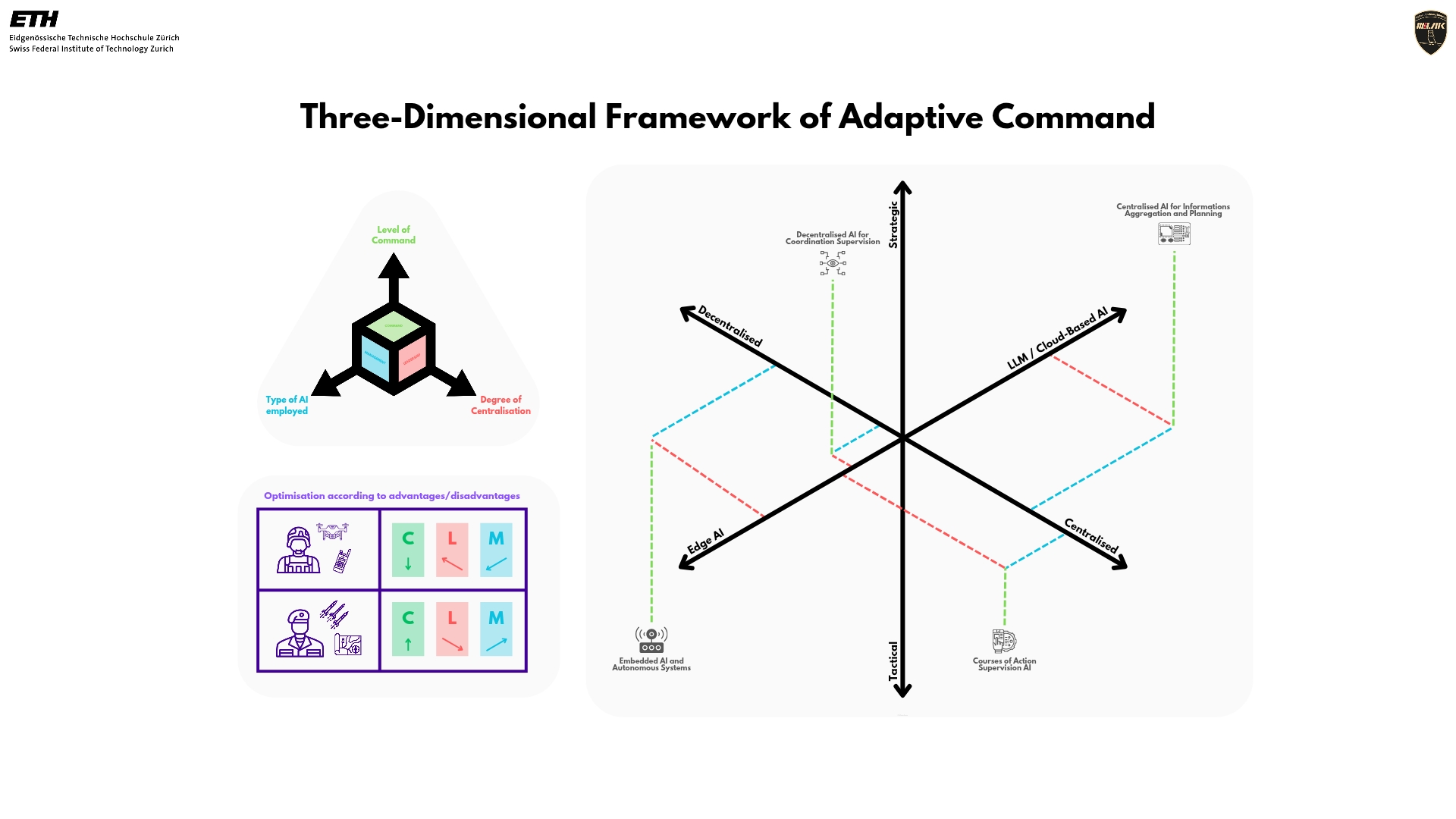

These analyses converge toward the necessity of a theoretical model of adaptive command capable of visually representing the dynamic flow between centralisation and decentralisation in the age of AI. One may envision a three-dimensional framework in which each axis corresponds to a key factor: the degree of command centralisation (ranging from fully centralised to fully decentralised), the level of command or scale of action (from strategic to tactical), and the type of AI employed (centralised cloud-based AI/LLMs, distributed Bayesian AI, embedded Edge AI).

Within this 3D space, command does not occupy a fixed point; instead, it moves within a volume of possibilities that reflect shifting operational demands. For instance, a deep special operation might be represented as a highly decentralised point on the tactical axis with a predominance of embedded AI. In contrast, an initial joint-force campaign could appear closer to the strategic-centralised pole, supported by intelligence aggregation AI systems. The model is dynamic: a trajectory or vector within this volume would illustrate the transition from one mode of command to another as the operation unfolds, responding to situational changes (emerging threats, communications disruption, windows of opportunity).

A deep special operation might be represented as a highly decentralised point on the tactical axis with a predominance of embedded AI.

The Command-Leadership-Management model enriches this tridimensionality: Command is parallel to the plane defined by the “level of command” axis, as it captures the doctrinal approach, the Leadership dimension aligns with the plane of the “degree of centralisation” axis, as it represents the human approach and Management lies parallel to the plane defined by the “type of AI employed” axis, as it reflects the structural approach.

Source: Authors.

Such a conceptual framework allows for the visualisation of transitions—for example, the gradual shift from centralised control at the onset of an engagement to increasing autonomy granted to subordinate units as the action becomes more complex, followed by a possible temporary recentralisation to synchronise a decisive effort, and so on.

It also reveals the specific contribution of the different domains, highlighting which dimension becomes predominant depending on where one is positioned within the model. The model, when applied to the three-dimensional space, provides both a critical and forward-looking perspective on future command: critical because it challenges military leaders to confront their cognitive biases (such as the tendency to over-centralise or relinquish control too readily), prompting continual repositioning along the optimal spectrum; and forward-looking, because it opens the way to novel, agile organisational forms enabled by AI.

Ultimately, command in the era of artificial intelligence may be understood as a complex adaptive system whose superiority lies in its capacity to reinvent its own modus operandi faster than the adversary. This doctrinal, intellectual, and structural agility—rather than any specific technology—will constitute tomorrow’s decisive advantage. The challenge is, therefore, not merely a dialectic between centralisation and decentralisation, nor simply a faster and more optimised OODA Loop, but rather a multidimensional dynamic in which doctrine, culture, and organisation each play an essential role.

Command in the era of artificial intelligence may be understood as a complex adaptive system whose superiority lies in its capacity to reinvent its own modus operandi faster than the adversary.

Meeting this transformation requires more than technical innovation. It demands new doctrines, cultures, and command structures suited for the AI era—ones that preserve the agile spirit and boldness inherent to Mission Command while leveraging AI to enhance the accuracy and speed of decision-making. The integration of AI forces a transition from abstract principles to concrete application: continuously adjusting the centralisation/decentralisation dial demands sustained intellectual discipline, organisational agility, and, above all, a doctrine fit for the future.

This proposed dynamic model is but a conceptual step toward that heightened agility: it provides a comprehensive framework for thinking about change—a necessary condition for implementing it within military doctrines, cultures, structures, and procedures.

Lieutenant Colonel Patrick Hofstetter, PhD, M.Sc., is Co-Head of Leadership and Communication Studies at the Swiss Military Academy at ETH Zurich. He is an active General Staff Officer in the Swiss Armed Forces. He serves as a training officer in the general staff for operational studies and training. His research interests are command, leadership, and management in the armed forces. He has published on tactical command and training in the Swiss Armed Forces and co-edited the anthology “Leadership Concepts: An International Perspective” (2024).

First Lieutenant Marius Geller is an infantry platoon leader in the Mountain Infantry Battalion 85, where he will soon assume company command. He is pursuing a bachelor’s degree at the Military Academy to become a career officer in the Swiss Armed Forces. His study interests are leadership as well as military sociology. As a career officer, he will coach and teach reservists.

Lieutenant Florian Gerster serves as a fire support officer in the staff of Artillery Group 1. He aims to become a company commander in the Reconnaissance Battalion 1. He is pursuing a bachelor’s degree at the Military Academy at ETH Zurich to become a career officer in the Swiss Armed Forces. His study interests are leadership, technology, and strategy in the armed forces. As a career officer, he will coach and teach reservists.

The views contained in this article are the authors’ alone and do not represent the views of the Swiss Armed Forces or ETH Zurich.

[1] James Johnson, “Automating the OODA Loop in the Age of Intelligent Machines: Reaffirming the Role of Humans in Command-and-Control Decision-Making in the Digital Age,” Defence Studies 23, no. 1 (2023): 43–67.

[2] René A. Herrera, “History, Mission Command, and the Auftragstaktik Infatuation,” Military Review, July–August 2022, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/July-August-2022/Herrera/, accessed March 21, 2025.

[3] Eitan Shamir, “Transforming Command: The Pursuit of Mission Command in the U.S., British, and Israeli Armies,” Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011.

[4] Department of the Army, “Mission Command: Command and Control of Army Forces (ADP 6-0),” Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, 2019.

[5] British Army, “Army Leadership Doctrine,” 2021, https://www.army.mod.uk/media/25267/cal-mission-command-and-leadership-on-operations-2024-final-v2.pdf, accessed March 21, 2025.

[6] Vitalii Shvaliuchynskyi, “Mission Command and Artificial Intelligence,” Review of the Air Force Academy 1, no. 1 (2023): 85–92, https://sciendo.com/pdf/10.2478/raft-2023-0010, accessed March 21, 2025.

[7] Richard Sanders, “Mission Command: Doctrinal Improvements for Peer Conflict,” Wild Blue Yonder 4, no. 2 (2023): 45–58, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Wild-Blue-Yonder/Articles/Article-Display/Article/3913449/mission-command-doctrinal-improvements-for-peer-conflict/, accessed March 21, 2025.

[8] NATO, “Allied Joint Publication AJP-01(D): Allied Joint Doctrine,” Brussels: NATO Standardization Office, 2022.

[9] Zoltán Fazekas, “Trust and Artificial Intelligence in Military Operations,” Tallinn: NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence, 2022.

[10] Alistair Byford, “How Well Do We Understand Air Command and Control?,” Air Power Review 17, no. 2 (2014): 92–97.

[11] Donald E Vandergriff, “Adopting Mission Command: Developing Leaders for a Superior Command Culture,” Minneapolis: Mission Command Press, 2018.

[12] Eitan Shamir, “Transforming Command.”

[13] Martin van Creveld, “Kampfkraft: Militärische Organisation und Leistung,” 1939–1945, Freiburg: Rombach, 1989.

[14] John Richard Boyd, “Patterns of Conflict,” Unpublished briefing slides, 1986, https://www.ausairpower.net/JRB/poc.pdf, accessed March 21, 2025.

[15] Réne A. Herrera, 2022, has written a more nuanced historical account of this, refuting some misunderstandings in the modern interpretation and also showing how the current understanding of Mission Command in the American armed forces is at best a half-hearted copy of the original.

[16] Robert L. Bateman, “Force XXI and the Death of Auftragstaktik,” ARMOR, January–February 1996: 13–15, https://www.benning.army.mil/armor/eARMOR/content/issues/1996/JAN_FEB/ArmorJanuaryFebruary1996web.pdf, accessed March 21, 2025.

[17] Rosario M. Simonetti and Paolo Tripodi, “Automation and the Future of Command and Control: The End of Auftragstaktik?,” Journal of Advanced Military Studies 14, no. 1 (2023): 85–102, https://www.usmcu.edu/Portals/218/JAMS_Vol14_No1_Simonetti_Tripodi.pdf, accessed March 21, 2025.

[18] Idem., 142.

[19] Pedro DeLeon and Paolo Tripodi, “Eliminating Micromanagement and Embracing Mission Command,” Military Review, July–August 2022: 19–27, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/MilitaryReview_20220831_art005.pdf, accessed March 21, 2025.

[20] James M. Beagle, John D. Slider, and Michael J. Arrol, “Mission Command in the 21st Century: Adapting to Modern Warfare,” Parameters 53, no. 1 (2023): 35–47, https://press.armywarcollege.edu/parameters/vol53/iss1/4/, accessed March 21, 2025.

[21] The latter has its justification, which can be explained by the “accountability chain” approach, see Patrick Hofstetter, “Der Mehrwert militärischer Führungsausbildung in der Staatsleitung: Von der Kaderschmiede zum Benchmark für Command, Leadership und Management in der Schweiz,” Zürcher Forum Staatsleitung, no. 10 (2025), https://www.ius.uzh.ch/de/staff/professorships/alphabetical/glaser/Z%C3%BCrcher-FORUM-zur-Staatsleitung/Der-Mehrwert-milit%C3%A4rischer-F%C3%BChrungsausbildung-in-der-Staatsleitung.html, accessed April 15, 2025.

[22] Patrick Hofstetter,“Command, Leadership, Management: 95 Thesen zur Führung in der Schweizer Armee und darüber hinaus,” Stratos 3, no. 2 (2023): 126–135, https://stratos-journal.ch/ausgaben/stratos-3-2/hofstetter/, accessed March 21, 2025.

[23] Stephen Bungay, “Mission Command in the 21st Century: A View from the Other Side,” British Army Review 150 (2011): 20–29, https://www.army.mod.uk/our-people/army-command-organisation/command-leadership-management/, accessed March 21, 2025.

[24] British Army, “Army Leadership Doctrine,” 2021, https://www.army.mod.uk/media/25267/cal-mission-command-and-leadership-on-operations-2024-final-v2.pdf, accessed March 21, 2025.

[25] Hofstetter, “Command, Leadership, Management.”

[26] Swiss Armed Forces, “Strategie zur Vision 2030 der Gruppe Verteidigung,” Internal document 81.377d, 2025.

[27] Jim Storr, “A Command Philosophy for the Information Age: The Continuing Relevance of Mission Command,” Defence Studies 3, no. 3 (2003): 119–129, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14702430308405099, accessed March 21, 2025.

[28] Vandergriff, “Adopting Mission Command.”

[29] Boyd, “Patterns of Conflict.”

[30] Patrick Hofstetter, Alan Borioli, and Till Flemming, “Manoeuvre Is Dead – But It Can Be Revived: Overcoming Stalemates by Gaining Competitive Advantage,” The Defence Horizon Journal, October 28, 2024, https://tdhj.org/blog/post/manoeuvre-innovation/, accessed March 22, 2025.

[31] Arthur K. Cebrowski, and John J. Garstka, “Network-Centric Warfare: Its Origin and Future,” Proceedings 124, no. 1 (1998): 28–35, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1998/january/network-centric-warfare-its-origin-and-future, accessed March 22, 2025.

[32] Shamir, “Transforming Command.”

[33] Edgar H. Schein, “Organizational Culture and Leadership,” 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1992.

[34] Vandergriff, “Adopting Mission Command”.

[35] Boyd, “Patterns of Conflict.”

[36] Idem.

[37] Idem., slide 76.

[38] Idem., slide 79.

[39] Carl von Clausewitz, “On War,” ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976), 102.

[40] Boyd, “Patterns of Conflict.”

[41] Frans P.B. Osinga, “Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd,” London: Routledge, 2006.

[42] Paul Scharre, “Army of None: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War,” New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018.

[43] Michael C. Horowitz, Lauren Kahn, Paul Scharre, and Megan Lamberth, “Algorithmic Warfare: Balancing Speed and Control,” Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2020, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1076-1.html, accessed March 21, 2025.

[44] Scharre. “Army of None.”

[45] Horowitz et al., “Algorithmic Warfare.”

[46] Vincent Boulanin, Netta Goussac, Sonia Fernandez, and Moa Peldán Carlsson, “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Strategic Stability and Nuclear Risk,” Geneva: United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR), 2020, https://unidir.org/publication/impact-artificial-intelligence-strategic-stability-and-nuclear-risk, accessed March 21, 2025.

[47] Boyd, “Patterns of Conflict.”

[48] Johnson, “Automating the OODA Loop,” 47.

[49] Horowitz et al., “Algorithmic Warfare.”

[50] Scharre, “Army of None.”

[51] Horowitz et al., “Algorithmic Warfare.”

[52] Scharre, “Army of None.”

[53] Boulanin et al., “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Strategic Stability and Nuclear Risk.”

[54] Horowitz et al., “Algorithmic Warfare.”

[55] Scharre, “Army of None.”

[56] Total Military Insight, “Rules of Engagement,” Accessed April 11, 2025, https://totalmilitaryinsight.com/rules-of-engagement/.

[57] Scharre, “Army of None.”

[58] For an introduction to the ethics of autonomous driving, cf. Patrick Lin, “Why Ethics Matters for Autonomous Cars,” in: Autonomes Fahren: Technische, rechtliche und gesellschaftliche Aspekte, ed. Markus Maurer, J. Christian Gerdes, Barbara Lenz, and Hermann Winner (Wiesbaden: Springer Vieweg, 2015), 69–85.

[59] Cf. Christof Heyns, “Autonomous Weapons Systems: Living a Dignified Life and Dying a Dignified Death,” in: Lethal Autonomous Weapons: Re-Examining the Law and Ethics of Robotic Warfare, ed. Nehal Bhuta, Susanne Beck, Robin Geiß, Hin-Yan Liu, and Claus Kreß (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

[60] Jean de Preux, “The Geneva Conventions and Reciprocity,” International Review of the Red Cross (1961–1997) 25, no. 244 (1985): 25–29.

[61] Michael Walzer, “Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argument with Historical Illustrations,” 5th ed. (New York: Basic Books, 2015), chapter 13.

[62] Boyd, “Patterns of Conflict.”

[63] Osinga, “Science, Strategy and War.”

[64] Sydney J. Freedberg Jr, “Empowered Edge versus the Centralization Trap: Who Will Wield AI Better, the US or China?,” Breaking Defense, February 2024, https://breakingdefense.com/2024/02/empowered-edge-versus-the-centralization-trap-who-will-wield-ai-better-the-us-or-china/.

[65]Benjamin Jensen and J. S. Kwon, “The U.S. Army, Artificial Intelligence, and Mission Command,” War on the Rocks, March 2025, https://warontherocks.com/2025/03/the-u-s-army-artificial-intelligence-and-mission-command/.

[66] Idem.

[67] Tim Stewart, “AI and the OODA Loop: How AI Enhances Strategic Decisions for Today’s Warfighters,” Military Embedded Systems, 2024, https://militaryembedded.com/ai/big-data/ai-and-the-ooda-loop-how-ai-enhances-strategic-decisions-for-todays-warfighters.

[68] Idem.

[69] Colin Demarest, “Exclusive: Gallatin, Backed by 8VC, Dives into AI-Fueled Military Logistics,” Axios, April 08, 2025, https://www.axios.com/2025/04/08/gallatin-ai-8vc-military-logistics.

[70] David S. Alberts and Richard E. Hayes, “Power to the Edge: Command… Control… in the Information Age,” (Washington, DC: CCRP, 2003), 62.

[71] Ellen J. Langer, “The Illusion of Control,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 32, no. 2 (1975): 311–328.

[72] Armée de Terre, “Qu’est-ce que le commandement par intention?,” Ministère des Armées (France), 2023, https://www.defense.gouv.fr/terre/chef-detat-major-larmee-terre/vision-strategique-du-chef-detat-major-larmee-terre/commandement-intention-0.

[73] Larry Wortzel, “Paper: Chinese Army’s Rigidity Inhibits Mission Command,” Association of the United States Army, 2024, https://www.ausa.org/publications/pla-and-mission-command-party-control-system-too-rigid-its-adaptation-china.