Abstract: Access to outer space is critical for all, small or big, and all countries are equal stakeholders of the Global Commons. It is essential for a host of activities, including civilian and security. Outer space is often characterised as ‘global commons,’ and the Outer Space Treaties have historically ensured the equal opportunity to explore space peacefully and prohibited national appropriation or sovereignty claims. The changing trends in space explorations and affairs are raising questions about the credibility of existing space norms and regulations. Geopolitical competition is taking place in space, and the investment in counter-space capabilities, commercialisation and human settlement in space is also increasing. However, the ‘first come, first serve’ principle makes it exclusionary as outer space becomes susceptible to being hegemonised. In the age of space commercialisation, while space is becoming more crowded and encountered by multiple interests, small aspiring countries may remain left out without regional or collective initiatives.

Problem statement: How to understand the necessity for space cooperation for aspiring nations?

Bottom-line-up-front: Regional power rivalries and threat perception between India and China, and India and Pakistan cause hurdles for a functional regional space cooperation. Regional cooperation is necessary to secure the interest of small aspiring states in space. However, due to the absence of space cooperation, small South Asian states will lag in using satellites for socioeconomic development.

So what?: Africa, a vast continent with many internal issues, can utilise the African Union as a common institution to enhance space cooperation. However, South Asia couldn’t use the existing platform like the South Asian Association for regional cooperation to do the same. Moreover, major space actors fail to unite due to regional geopolitical rivalries. In that case, it will not only hamper the possible economic growth of developing nations but also the uneven space technological development will create a hegemonic regional order. This can create security threats to small countries.

Need for Space Cooperation

Outer space is no longer a domain of wealthy and powerful states. The trends of space exploitation have also changed in various sectors. Major spacefaring countries are investing in counter-space capabilities, commercialisation, and resource exploitation. With all these changes, space exploration is being increasingly democratised, and technological globalisation has attracted formerly peripheral developing states of the Global South – including from the African continents and the Indian sub-continent – to this new frontier. Historically, major powers have dominated space affairs, and knowledge power nexus facilitates privilege to few countries. However, private companies’ engagement in space exploration opened the door for many countries, including aspiring and non-spacefaring states.

Major powers have dominated space affairs, and knowledge power nexus facilitates privilege to few countries.

In many cases, private companies have significantly lowered the financial threshold for least-developed countries to access space. For example, U.S.-based private company SpaceX launched Bangladesh’s first satellite.[1] SpaceX provides Starlink satellite support to many developing states besides launching satellites for other countries. In 2023, SpaceX will be providing Starlink service in Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda, Mozambique, and Zambia, and SpaceX has also approached many South Asian states to expand Starlink connectivity. The growing commercial engagement is incredibly changing the trends of space explorations. Major spacefaring countries encourage commercialisation and push private actors’ investment in space exploitations. At the same time, increasing private actors’ engagement changes the space race’s traditional nature. The space race is now more about economic and strategic interests. Space-power countries have focused on lunar expeditions for resources for the last few years. Many private companies have declared they will build human settlements on the Moon and Mars. “For Bezos, the goal is free-floating space colonies; for Musk, near-term colonisation of Mars is the paramount- and quite achievable –goal”.[2] Now, all these changes are affecting newcomers’ aspirations of space exploration. Lunar competition is now at the highest pick. One side, the U.S., called for the Artemis Accords in 2020; now, 33 countries have signed the accord, including India.[3] On the other side, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Russia also announced the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) program in 2021, with five additional countries joining since.[4] Hence, all these changes are opening the door for many countries to participate in lunar explorations. However, the consequence of selecting one party against another also limits the possibility of universal space cooperation among countries. So, one way or another, small aspiring states will be victims of astropolitical rivalries and the modern space race.

The irony is that space is a trillion-dollar economy. Unfortunately, space economics, utilising space technologies and services for economic development, or exploiting space resources are still not available for a larger portion of the world. The benefits of this economy do not reach all countries.

In 2015, the U.S. passed the Space Act, which allowed U.S. companies to mine Asteroids. The question is whether this law violated the Outer Space Treaty (OST) principles or not. By the Moon Treaty 1979, “neither the moon nor its resources “shall become a property of any state, international intergovernmental or nongovernmental organisation, national organisation, or nongovernmental entity, or of any natural person,”[5] neither the United States nor any other major spacefaring nation has ratified it And it’s not only US., other countries like Luxemburg and UAE’s domestic space laws in support of ensuring right of mining and commercialise space resources challenges the OST.

This renewed interest in outer space has put into stark focus the ambiguity of the international instruments on the use of outer space. There are persisting unresolved issues related to outer space, such as the demarcation of the border between space and atmosphere, which varies country by country.[6] The dependency on space-based services and heightened demand for space resources have increasingly made the domain competitive, contested, and congested.[7] The use of space-based assets in the Starlink satellite constellation in the Russia-Ukraine War and the Anti-Satellite Tests (ASATs) has also refocused attention on the possibility of war in outer space.[8]

There is a technological revolution underway in space-based technologies. However, the benefits of these technological advancements are unevenly distributed worldwide. Development and space programs have remained West-centric and West-driven for the longest time. While there is an increasing participation and stronger presence of many countries from Asia, Africa, Latin America, and West Asia,[9] they still struggle with building space infrastructure and running launch programs. This is due to weak economic positions and a lack of technological know-how. And even in many cases, major space actors have used former colonies or equatorial states as spaceports or launching sites. Equatorial nations have a unique advantage in space. Due to the closer to the equator, if any of these countries launch satellites from the equator, less fuel will be needed to bypass the atmosphere. This is why the European Space Agency (ESA) has been using French Guiana as a launching site. Equatorial states, or countries nearer to the equator, can utilise geographical advantage by letting other space-power countries use their location as launching sites, strengthening their economic position. For example, “the Russian-operated Baikonur Cosmodrome in southern Kazakhstan. Although the Soviet spaceport was in its operator’s homeland when it was established in 1955, Kazakhstan gained independence in 1991, and Russia began paying to lease the launch facilities soon thereafter. Today, Russia pays Kazakhstan approximately $115 million annually in order to maintain access to the spaceport.”[10]

Many South Asian countries are located near the equator. India launched most satellites from Satis Dhawan Space Center at Sriharkota and will establish a second spaceport in Tamilnadu; both spaceports are close to the equator and potential sites for geostationary satellites. Sriharikota is located near the equator, which gives the satellite extra force from the Coriolis effect and saves fuel. Other than India, two other South Asian countries, the Maldives and Sri Lanka, are the closest states to the equator, but these two countries don’t have spaceports and space capabilities. So, if countries like Maldives and Sri Lanka can establish spaceports with the help of other space power countries for commercial launching purposes, it will evolve these states in space economy. Unfortunately, due to a lack of technological capacity, these South Asian countries couldn’t use their geographical advantage to benefit from the space economy. So, these countries can only be technologically self-sufficient with the help of regional space cooperation.

Space-technology cooperation is related to critical security aspect of technology transfer. The dependency on other space power countries for space-related services like GPS or PNT has long-term implications. For example, the PRC is trying to expand the Beidou navigation service in South Asia. The Beidou project is a significant part of PRC’s ‘Space Silk Road’ policy. The PRC targets those countries (already under Belt and Road initiatives) to use these navigation services. As per the PRC’s White Paper 2016, Beidou is a major strategic part of BRI.[11]

On the other hand, in terms of navigation satellite technology, India recently inaugurated the Navigation with Indian Constellation (NaVIC), also known as the Indian Regional Navigation Satellite System (IRNSS). NaVIC can provide real-time positioning and timing service to India and its border areas up to 1500 km. India didn’t offer NavIC regionally or globally yet. According to the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) chairman, the NaVIC system was not in a “full-fledged operational regime”.[12] However, every country needs global ‘Positioning, Navigation and Timing’ (PNT) services for civilian and security purposes. Although most South Asian states depend on U.S.-GPS support, countries may soon take this service from the PRC, which could challenge India’s interest in the region.

Shortcomings of Outer Space Treaty and Regulation Gaps

The ‘Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space,’ commonly referred to as ‘Outer Space Treaty’ (OST),[13] established celestial bodies as global commons. However, the treaty has several loopholes and ambiguities that the major space powers exploit. This includes provisioning orbital slots, especially in the geosynchronous orbits (GSO) occupied on a ‘first come, first serve’ basis. Increasing commercialisation of space and the launch of large satellite constellations comprising thousands of satellites in the low (LEO) and medium (MEO) earth orbits is shrinking the room for aspiring space powers. “Jonathan McDowell in an interview with Space.com said: “it’s going to be like an interstate highway, at rush hour in a snowstorm with everyone driving much too fast.”[14] In the coming year’s space competitions for large constellations by state and private actors will increase the risks of “orbital conjunction”. Hugh Lewis stated that “the overall number of conjunctions predicted for 2022 was 134% higher than the number for 2020 and 58% higher than 2021, exceeding 4 million”.[15] Major spacefaring states already occupy orbital slots of GEO and LEO, so newcomers are not getting expected slots; either the slots are occupied, or there is a vast number of applications against one slot. For example, in Bangladesh’s case, it approached the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) for a 102-degree east orbital slot. ITU rejected it because, before Bangladesh, 20 other countries also applied for the same slot. Then Bangladesh rented an orbital slot from Russia by paying 2.18 billion. Lastly, Bangladesh got 119.1 degrees east and successfully launched its first satellite in GEO.[16] Though outer space is considered global commons, in the case of GEO, the rules of obtaining slots somehow create a barrier for developing countries. If a few countries or private companies already occupy the GEO slots, then there are only two options for small countries: rent or wait for it. In the case of Bangladesh’s first space mission, it paid a heavy amount to a Russian space company. As the GEO has limited satellite capacity, the competition for slots will be more intense in the coming years.

Increasing commercialisation of space and the launch of large satellite constellations comprising thousands of satellites in the low (LEO) and medium (MEO) earth orbits is shrinking the room for aspiring space powers.

Space-based services are critical for both state affairs and civilian applications. Effective use of space for socioeconomic development could be a game changer for developing countries. Innovation and rising investments in the space sectors have reduced the cost of entry barriers for many states, bringing space exploration within the realm of possibility for the countries of the Global South. With major space powers already having a host of space-based assets, entry of commercial players with huge financial backing, and aspiration space powers from the developing world making forays into outer space, ensuring equitability in access and distribution of resources of these global commons will be a challenge.

The increasing number of satellites have congested the LEO and exacerbated the space debris problem. Per the Space Surveillance Network (SSN) of the United States Space Force (USSF), over 27,000 pieces of trackable debris are in the LEO today. This increasing amount of space debris poses a significant risk to all actors.[17]

The ambiguity of OST also brings up sovereignty threats for countries of the Global South that cannot control their airspace based on their understanding of the separation between outer space and the atmosphere. Conventional and customary rules of international law do not define where airspace ends and outer space begins. This uncertainty has created a regulatory legal gap in safety and navigation, creating multiple risks. Such uncertainty also affects private investments. The position of the U.S. is that outer space starts at an altitude of 50 miles.[18] However, most of the international community has accepted the Karman Line (altitude of 62 miles) as the de facto boundary of airspace and outer space. Considering these differences between the positions of essential actors, outer space could be abused and cause confusion and misperceptions. Countries with limited resources may not be able to do much to resist the misuse of the airspace.

Airspace is intrinsically tied to states’ sovereignty and security. The confusion around the demarcation of outer space boundaries makes them vulnerable to spying. Thus, there is no right of innocent passage through sovereign airspace for foreign aircraft, and such a right of innocent passage of foreign space objects in outer space can challenge technologically backward nations in terms of space technology, who will not be able to figure out what is happening above their sky. It’s no longer a secret that countries use satellites for spying and surveillance. So, when only a few states have dual satellites and counter-space capabilities, the aspiring spacefaring states are already vulnerable in the domain. This is why many new countries are investing in military satellites and counter-space capabilities. Since the 1960s, the United Nations has been working to prevent the weaponisation of outer space. Several treaties were passed in this regard, like the Partial Test Ban Treaty and Outer Space Treaty. The existing space governance couldn’t eliminate irresponsible behaviours in terms of deployment of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) or nuclear weapons in space objects or kinetic tests in space. Although the Partial Test Ban Treaty and Outer Space Treaty ban the placement of WMD in outer space, they don’t prevent the placement of other types of conventional weapons. These loopholes are misused by major space power, and counter-space capability tests by countries are increasing. However, Russia and the PRC joined, given a proposed draft, “Treaty on the Prevention of Placement of Weapons in Outer Space,” 2008. Still, the U.S. opposed it because the proposed draft does not add land-based anti-satellite weaponry. Conversely, the U.S. Government proposed a treaty against the ASAT test in the United Nations and committed not to conduct destructive, direct-ascent anti-satellite missile testing.

Outer space is a global commons, like the high seas and Antarctica. The major commonality among the three global commons is the growing commercialisation by great powers. Due to technological superiority, only a few countries benefit from global commons resources. Interestingly, OST was also shaped by the high seas and Antarctica treaties. The Law of the Sea and Outer Space treaties have almost the same clauses. “Article 87 of the High Seas says high seas are open to all States, coastal and land-locked. High sea treaty also affirmed that resources of the sea are the common heritage of mankind, and resources must be utilised equitably by all actors”.[19] However, the growing commercialisations and unregulated fishing created threats to the environment. Fortunately, countries can come together to take steps to protect international water and ocean biodiversity. “As of October 2023, 80 countries have signed the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) agreement”.[20] However, in the case of outer space, which is also facing similar issues, the increasing space arms race, mega-constellations, and debris issues will threaten the space environment. There is a need for a new agreement advocating debris mitigation and sustainable use of space resources so newcomers don’t become victims of debris and can get equitable benefits from global commons resources.

Outer space is a global commons, like the high seas and Antarctica.

However, the demarcation of boundaries and governance mechanisms is not settled yet. While the legal status of outer space was not clear before the launch of the first satellites, there were precedents, such as the freedoms of the high seas, to suggest that orbital space would be used free for all states. The launch of space satellites by the U.S. and the USSR was not protested, nor was the overflight over sovereign territory. Freedom of space was established in 1961 through the UNGA Resolution 1721 in 1961, which states that “outer space and celestial bodies are free for exploration and use by all states in conformity with international law and not subject to national appropriation.[21] Article I of the OST also declared that “every state should enjoy these rights irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development… without discrimination of any kind, based on equality”.[22]

The OST, however, does not restrict spacecraft launching into space, orbiting or sending spacecraft to celestial bodies, or returning the spacecraft to Earth. Even if the orbits may pass over state territory, it does not violate sovereign airspace. Thus, OST reflects many of the tenets of the law of the high seas, which accords freedoms to all states, including landlocked states. The only restriction is the vague principle that all activities in space must be “peaceful.” However, growing militarisation also questioned OST’s applicability in the present space age. Till today, four space power countries have tested ASAT weapon systems, but these tests created vast space debris. Russia used ASAT to destroy an old satellite in 2021, which has created debris threats to the International Space Station (ISS). According to Secure World Foundation, “at least 16 debris-creating ASAT weapons tests have been taken place by major powers to date, the PRC’s’s ASAT in 2007, as the country blew up its weather satellites and created 3,000 pieces of debris. India tested ASAT in 2019. In the U.S., the first ASAT test was back in the 1950s, and since then, the country has conducted at least three ASAT debris-creating tests; two in the mid-1980s and one in 2008”.[23] Still, the treaty Governing the Activities of states in the exploration of outer space, the moon, and other celestial bodies, the Liability Conventions 1972 (For making actors liable for damage caused by space objects and assuring consultations and compensation ), and the Registration Convention 1976 (Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space 1976) can apply in addressing space debris; these three regulations can be used in addressing space debris, but do these treaties are sufficient, or which extent international space governance able to take against irresponsible behaviours of state and non-state actors? Articles 6, 7, and 9 of OST may apply to defined space activities regarding damage and compensation. The aim of mega-constellations on LEO by state and private actors will create environmental challenges, a real concern for all countries.

Uses of Satellites and Space-Based Assets

All countries are dependent on satellite-based services. Satellites are widely used to support navigation, communications, and remote sensing for civil and military purposes. The daily lives of people of any country increasingly depend on satellite-based services like GPS, telecommunication, telemedicine, weather forecasting, precision agriculture, land and ocean surveying, resource mapping, early warning, and disaster management systems. The major intention or compulsion of adopting satellite-based services of developing states is mostly for civilian purposes but can’t be apolitical or beyond military interest. Developing African and South Asian states are trying to adopt space-based technologies to overcome socioeconomic challenges. However, developing states subsequently depend on major space powers due to a lack of capacity building and economic capacity. However, long-term dependency on foreign powers for several space-based services has larger consequences because aspiring spacefaring countries are paying spacefaring states for space-based services and data. Space applications are necessary for monitoring the environment and providing early warning about natural disasters. Communication facilities in remote areas, education, agriculture, health, banking and transportation are now largely dependent on satellite.

The U.S.-owned GPS, Russia’s GLONASS, the European Union’s Galileo, the PRC’s BeiDou, and India’s NavIC compete in the navigation/PNT market. GNSS services have huge military implications, which cannot be ignored. Until today, GPS is the most popular navigational and positioning service. The U.S. announced, “GPS service is a gift to the world”,[24] and the political implication of this service is huge. In the case of South Asia, all countries depend on GPS systems, but the PRC is trying to counter the GPS market. The PRC has already expanded BeiDou service to many African countries through the BRI. The PRC claims that half of the world’s countries now use Beidou services, consisting of 35 satellites, and the country also exported navigation products to 120 countries.[25] As Beidou facilitates a two-way communication system, it can identify the receiver’s locations and Beidou-compatible devices can transmit data back to the satellites.[26]

The U.S.-owned GPS, Russia’s GLONASS, the European Union’s Galileo, the PRC’s BeiDou, and India’s NavIC compete in the navigation/PNT market.

However, as it is standard, only a few countries can produce such advanced satellites, and even fewer can launch them into orbit. Only four countries, namely the U.S., Russia, the PRC, and India, have demonstrated the capacity to target a satellite in orbit. There are also mentions of space colonisation and using it to exploit mineral resources from celestial bodies in outer space. The developing world is trying to enhance its abilities in this area, but the space programs in various regions are not even flourishing uniformly.

The Failed Promise of Space Cooperation

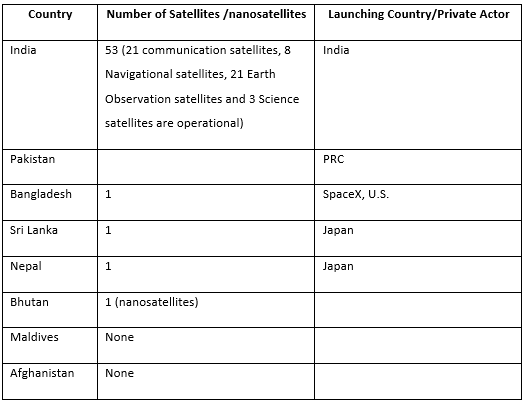

South Asia is a territorially smaller region housing a significant chunk of the global population. It comprises just eight countries. India is a major regional spacefaring power, whereas others are aspiring space powers. Since India’s independence, the country has launched 129 satellites for domestic purposes and launched 349 foreign satellites on behalf of 36 countries.[27] India’s space program is unique to other space powers because it emphasises cost-effectiveness and sustainability.[28] In recent years, India has provided space services and support regionally and globally and helped other countries launch satellites. India also achieved defensive space capabilities demonstrated through ASAT in 2019.[29]

Other than India, the rest of the South Asian countries do not have any significant space-based capabilities. Despite having an important space power in the region, there has not been sufficient diffusion of space-based capabilities. South Asia is a region that is connected not only spatially but also historically and culturally – much like Africa. Nevertheless, it lags far behind in terms of cooperation. A significant reason for this is the animosity between India and Pakistan. The countries have failed to resolve long-standing border disputes and are engaged in regional competition. India and Pakistan also possess nuclear weapons, which renders the hostilities in the region more sensitive than they would otherwise be and more intractable due to the fear of mutually assured destruction. South Asia is a geopolitically vital region and has drawn the attention of regional and global powers, especially the U.S., the PRC, and Russia. The countries in the region are thus susceptible to intra-regional rivalries or extra-regional interferences. This geopolitically fragile situation spills over to the domain of outer space and space cooperation. Regional initiatives usually perish at the altar of internal challenges. This makes it difficult for the region to sustain space programs; thus, it lags others in this domain.

South Asia has uneven economic development and struggles with profound social, political, economic, and environmental challenges. Technological capabilities and development are also not equal in the region. Seven out of the eight countries have nascent space programs. Small and developing countries require space capabilities to deal with their severe socioeconomic and developmental problems. As per the United Nations for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) and the European Global Navigation Satellite System Agency study (2018), out of 169 targets, 65 SDGs benefit from using Earth observation and navigation satellite systems.[30] South Asian countries are also disaster-prone and especially vulnerable to changes due to global warming. Thus, early warning systems for disaster management and agriculture protection are critical applications of space-based assets for the countries of this region.

Economic interest and traditional and non-traditional security issues remain essential in pursuing outer space programs in South Asian countries. In the context of regional cooperation, the region is far behind compared with Europe and Africa. Regional geopolitical rivalries, disputes, distrust, and external influence are significant barriers against space cooperation in South Asia. Unfortunately, regional organisations like the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) have failed to effectively enhance technological or scientific knowledge sharing. The distrust between India and Pakistan remains a significant barrier to space collaboration and cooperation. Conversely, a country like the PRC remains an external overbearing influencer in South Asian politics and regional order. The PRC’s assistance to Pakistan’s space program could have security implications for India or others.[31] Though India contains an advanced-level space program, the existing geopolitical rivalries between India-Pakistan and India-PRC rivalries have implications for delaying integrated space cooperation in South Asia.

All South Asian countries are trying to achieve the UN’s sustainable development goals (SDGs). No state of the continent can deny the role of space service in economic growth development. The geopolitical complexity always creates a dilemma for small countries to seek cooperation and collaboration from major countries like India or the PRC.

No state of the continent can deny the role of space service in economic growth development.

Hence, space is a domain where any aspirant needs high technological knowledge, innovation, economic capability, and labour. Small states cannot build critical space infrastructure without regional space cooperation and collaboration.

Many regional and sub-regional initiatives have been taken in South Asia, including the SAARC established in 1985, and the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), founded in 1997. Both initiatives have failed to live up to the promise of enhancing regional connectivity and cooperation. Both commit to cooperation in scientific innovation and technical collaboration.

The Curious Case of ‘SAARC Satellite’

India’s role in space cooperation has a global dimension as well as a regional dimension. In 2014, India offered the ‘SAARC Satellite’. India is the only spacefaring nation that offered a regional satellite in 2014 to its neighbours to help with disaster management and natural calamities, and ‘Prime Minister Modi said, “Even the sky is not the limit for regional cooperation.”[33] India’s proposal to bring the whole of South Asia under one satellite umbrella was a major part of the’ Neighbourhood First’ policy. India also launched Navigation with Indian Constellation (NavIC), India’s first indigenous global navigation satellite system. NavIC will be operational from 2023 and facilitate accurate real-time positioning and timing service over India and the region. Till now, NaVIC is not fully functional. However, India’s NavIC constellation could be a new way of regional cooperation, but the U.S. Global Positioning System (GPS) is already playing a significant role in disaster management. For example, during the tsunami of 2004 in the Indian Ocean region and the Pakistan-India earthquake in 2005, GPS was used in disaster management. The navigation market could be a new area of economic and strategic competition. It has huge importance in achieving Socioeconomic development and countering non-traditional security issues like disasters and food security. So, India’s NaVIC services can be used in regional disaster management sectors.

However, will SAARC countries welcome India’s NAVIC and adopt it regionally? South Asian states mostly use U.S.-based navigation systems (GPS). Since 2020, the PRC has been trying to negotiate with small South Asian countries, like Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, to adopt the Beidou satellite (BDS) navigation system. Initially, Bangladesh and Nepal were optimistic about adopting a BDS navigation system; in that reference, the PRC invited Nepal officials to Beijing to train on the Beidou system.[34]

The agenda of building the SAARC satellite was building connectivity throughout the region through space satellites and services. However, the project was not as successful as it may seem initially because of Pakistan’s disagreements.[35] There was some scepticism among other states on sharing one satellite for the region. Notwithstanding, India’s space diplomacy and bilateral relations with its neighbours made the satellite project possible.

India had to rename the SAARC satellite South Asia Satellite, which all SAARC countries other than Pakistan welcomed. It is primarily a communication satellite providing support in various areas, including internet connectivity, direct-to-home television, tele-education, telemedicine, disaster management, meteorological applications, fishing and agricultural advisory notices, and natural resource mapping.”[36] India launched the South Asia Satellite in 2017 to facilitate wide-ranging communications and meteorological support. The satellite launched into geosynchronous with a mission life of more than twelve years.

Since then, many regional countries, such as Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Bhutan, have launched satellites or nanosatellites, and Maldives have started their space research program.[37] The major drivers behind African or South Asian countries’ space ambitions are social, economic, and environmental issues. As a setback for South Asia, small South Asian states have failed to attract regional or global space powers to invest, assist, or cooperate in a regional space program. The experience of the South Asian satellite or SAARC satellite project has disillusioned India and other South Asian countries from cooperating in space-based projects and created a trust deficit.

The major drivers behind African or South Asian countries’ space ambitions are social, economic, and environmental issues.

Africa and South Asia share similar legacies. Both regions have colonial trauma and remained vital in global power politics; both “have common socioeconomic crisis such as large populations, political instability, poverty, unemployment, epidemic, and pandemic-like issues”,[38] and each continent falls within the Global South, where most of the countries are least developed or developing. Countries of both regions are also mired in various traditional and non-traditional security issues, such as terrorism and climate change. Nevertheless, Africa has paved the way in demonstrating how a region can cooperate on specific issues despite differences and divergences.

The African Model for Space Cooperation

Africa is a region with immense cultural and ethnic diversity. Political and economic instability is also a thread connecting many of the countries in the region. African countries, much like the countries in South Asia, have been victims of colonialism, ethnic conflicts, civil wars, political instability, corruption, terrorism, poverty, and climate change. Many region countries have simmering conflicts that could flare up at any time.[39] Africa is also a site where geopolitical competition of the great powers plays out. Global powers have competed to mould Africa’s social, cultural, political, and economic landscape to secure their interests. This has been true since the Scramble for Africa in the 19th century to the present day.[40]

Despite these challenges, Africa has united and jointly agreed on a regional space policy and program. Several reasons have led to this. First, the space program is associated with prosperity and is a way to project power and prestige. African countries have been mired in various socio-political issues and dealing with a developmental deficit; they want to create a positive image for the continent as it can help attract further investments and usher in a virtuous cycle. Second, space-based services are important for telecommunication, weather forecasting, disaster management, banking systems, and agriculture. All of these contribute heavily to the economic development of the continent. Third, due to this need, African countries must unite and build capacity and capabilities in the space sector. There is a conscious realisation in the African Space Policy that it is a net importer of space technologies. Without indigenous development of technologies, external dependency adversely affects the region’s socioeconomic development, security, and independence. Fourth, the enhanced communication and connectivity provided by space technologies also help ensure regional security from non-traditional security threats, including terrorism, and strengthen regional security in the process.

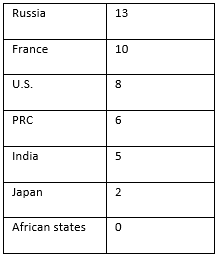

To date, 20 African states have space programs. Among them, 13 countries have space agencies like Algeria, Angola, Egypt, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe, and presently 48 African satellites are orbiting in space.[41] African countries’ budget for space was $325 million in 2019, and in 2022, it reached $535 million and “as of June 2023, 15 African nations have invested over 4.71 billion USD in 58 satellite projects. The launch of additional 105 satellites by 2026 is anticipated”.[42] Considering African states’ space budget, it can easily assume the region’s growing interest in the domain.

How Is Africa Utilising Major Powers’ Competition in Favour of its Space Development?

An interesting part of the African regional space initiative is that African countries cleverly utilised great powers’ interest in Africa, which helped the region to get funds and technological cooperation from leading space power states. African nations are increasingly collaborating with existing space powers, like the U.S., the PRC, India, and European states, to develop their ambitions in the domain. The PRC promotes ‘Space Silk Road Policy’ worldwide, including in Africa and Asia. Taikonautes are training African space scientists and the PRC assisted Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Namibia to start the space journey.[43]

According to Temidaya Oniosun, a Nigerian space scientist, “the space industry in Africa is growing at an incredible rate. Hence, countries and regions like the PRC, Europe, Russia, and the U.S. are beginning to compete for a stake in the industry”.[44] The PRC’s space cooperation in Africa is part of its Belt and Road initiatives. Hu Changchun, the head of the PRC’s mission to the African Union (A.U.), said “space cooperation in Africa is also an inclusive part BRI project. African people will explore space under the guidance of BRI initiatives, and the PRC is sharing satellite resources and training African scientists and researchers”.[45]

In the case of Africa, countries of the region have successfully benefited from great powers’ interest in Africa and strategically utilised the assistance of the U.S., the PRC, Japan, and European countries to build an advanced space program.[46] With this assistance, African states have tried to develop indigenous space programs and reduce dependency on foreign technology. African countries established the African Space Agency on January 30, 2023.

In Africa, there is also a shift in perceptions of space technology. Access to space technology is not a luxury anymore; rather, it is considered critical infrastructure. This contributes to building an emerging network of scientists, entrepreneurs, investors, and agencies who dedicatedly contribute to raising capital for space technology, both from within and outside the continent. There is an interest in developing space capabilities to address matters of socioeconomic importance.[48]

In Africa, there is also a shift in perceptions of space technology.

Despite its internal and external challenges, African states have managed to unite and build a regional space program under the A.U. umbrella, collaborating on several space-related initiatives. Africa is the fastest-growing regional participant in space, and many African states have already developed their national outer space programs. The A.U. has played a decisive role in creating ‘The African Outer Space Program,’ aiming to add synergies and benefit the continent. African Union’s first space initiatives were framed in 2015 during the 24th African Union (A.U.) Summit. In this summit, African states adopted ‘Agenda 2063.’ The eleventh number agenda of Agenda 2063 is about making an ‘African Outer Space Strategy’ to boost the continent’s economy and prosperity. Moreover, it also talks about building appropriate policies and strategies to develop a regional market for regional space products.[49]

Similarly, ‘the African Space Strategy, adopted in 2016, is based on the belief that the role of space technologies in addressing the socioeconomic challenges faced by the region’s states cannot be outsourced. The agenda argues that Africa cannot afford to remain a net importer of space technologies because this will hamper its economic development, security, and independence in the long run’.[50] This being the case, African states come together to build indigenous capacities. African countries recognised that members of the region should work together to ensure their citizen’s basic needs and comprehensive security like food, health, and environment.

Major spacefaring nations can utilise space capabilities to leverage them for geopolitical goals, economic development, and commercial and security interests. The U.S., the PRC, Russia, Japan, France, the UK, India, Israel, South Korea, UAE, Italy, Brazil, North Korea, and Iran are major spacefaring nations. It could be reasonably expected that developing countries with limited space capabilities would focus on the developmental aspect. Curiously, African countries have been increasingly investing in the space sector for both civilian and military quests. This is only possible because they have leveraged external interest in the African space industry to build indigenous capacities and provide sufficient incentive to external powers to contribute to these ambitions.

Prospects of Functional Cooperation On Outer Space in South Asia Through Multilateralism

India can offer substantial assistance to its neighbours. Regarding bilateral and multilateral engagements, “India has over 230 space agreements with 60 countries and 5 International Organizations”.[51] Pakistan started its space program in 1962 and initially showed promise, but it has struggled to grow due to its political environment, economic crises, and lack of technology. Pakistan is the only country in the region to have taken direct Chinese assistance in this respect. However, the PRC’s regional ambitions are much larger, reflected in its developmental ‘Belt and Road Initiative’. The PRC can build on this and aid South Asian nations. Pakistan and Bangladesh are both signatories to the PRC’s regional space initiative, the Asia-Pacific Space Cooperation Organization.[52]

However, due to the Sino-Indian competition, the region’s countries must walk a tightrope in seeking or accepting such assistance from the PRC. On the other hand, most of the South Asian countries are members of the Asia-Pacific Regional Space Agency Forum (APRSAF) that Japan governs.[53] Japan can be an alternative for the region’s countries to help shore up their space capabilities. The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD)[54] is another initiative that could be a choice for small countries in the region. The QUAD has already expanded its cooperation and connectivity network in South Asia. India, already a member of the QUAD, could use the platform to assist the other countries of the region in collaboration with other members of the QUAD. This would be a way to increase the legitimacy and acceptability of its assistance and bypass potential issues caused by intra-regional differences.

BIMSTEC also has a Technology Transfer Facility (TTF) Memorandum of Association (MoA), signed on March 30, 2022. The TTF MoA aims to coordinate, facilitate, and strengthen cooperation among member states in space technology applications, information and communication technology, nanotechnology, biotechnology, and other critical and emerging technological areas.[55] Countries need to isolate such initiatives from the broader geopolitical contexts. This can be done by keeping the initiatives away from the higher levels and packaging them as science and technology cooperation at sub-national levels.

The integrated regional space policy framework and cooperation can help smaller South Asian countries build independent space programs. However, the primary missing point in existing regional cooperations is insufficient collaboration in capacity building and the lack of knowledge sharing. Undoubtedly, APSCO and APRAF are assisting in satellite development and space research. However, both organisations prioritised the Asia-Pacific region more, where South Asian states got limited benefits.

A Need, Not A Luxury

Space technology is no longer a luxury. However, significant costs are associated with development in this domain that are difficult for small and developing states to meet. Cooperation is the only way to obtain connectivity advantages from the developed space sector. Cooperation helps achieve capacity building, cost-sharing, redress common challenges, and enables equitable access to global commons like outer space. Domestic ability to utilise space-based service and resources are now essential for African and South Asian states.

Cooperation is the only way to obtain connectivity advantages from the developed space sector.

Most of the countries of these two regions are developing or least developed countries. These two regions are struggling to achieve UN Sustainability goals. However, building a regional space program and infrastructure will reduce the gap and assure equal opportunities and benefits for all aspiring countries. Access to outer space is equally crucial for advanced and least developed states. Aspiring countries can access space services or objects through knowledge and technology sharing. However, in the case of South Asia, this cooperation is absent due to mutual distrust and geopolitical rivalries. Through functional cooperation in multilateral organisations, South Asian states can overcome and set out on a path like that of the African continent, which is increasingly being recognised as an important player in the future use of outer space.

Most Farjana Sharmin is a doctoral candidate with research interests in international relations, astrology, space security, and sustainability.

Yug Desai, doctoral scholar, governance of Emerging technologies.

The views contained in this article are the authors’ alone.

[1] Henry Caleb, “SpaceX launches Bangladeshi satellite on debut Block5 Falcon 9 mission,” SPCANEWS, May 11, 2018, https://spacenews.com/spacex-launches-bangladeshi-satellite-on-debut-block-5-falcon-9-mission/.

[2] Daniel Deudney, “Dark Skies Space Expansionism, Planetary Geopolitics &The Ends of Humanity,” Oxford University Press, 2020: 24.

[3] Lea, Robert,“ The Artemis Accords lay out the framework for collaboration nations as we enter the next era of lunar exploration and beyond”, Space.com, December 05, 2023, https://www.space.com/artemis-accords-explained.; “The Republic of India Signs the Artemis Accord,” U.S. DEPARTMENT of STATE, OFFICE OF THE SPOKESPERSON, June 24, 2023 https://www.state.gov/the-republic-of-india-signs-the-artemis-accords/; Suchita Karthikeyan, “Explained |Artemis Accords, India-US space collaboration and how it relates to ISRO’s missions,” THE HINDU, June 27, 2023, https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/science/explained-artemis-accords-india-us-space-collaboration-how-will-it-affect-isros-mission/article67008488.ece.

[4] “Partner nations on China’s lunar research station program,” Reuters, October 26, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/science/partner-nations-chinas-lunar-research-station-programme-2023-10-26/.

[5] United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, “Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies,” United Nations resolution 34/68, 1979, https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties/intromoon-agreement.html.

[6] Gbena Oduntan, Sovereignty and Jurisdiction in the Airspace and Outer Space: Legal Criteria for Spatial Delimitation, Routledge Research in International Law, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2012, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9780203807552.

[7] UN.org, “Outer Space Increasingly ‘Congested, Contested and Competitive’, First Committee Told, as Speakers Urge Legally Binding Document to Prevent Its Militarisation | UN Press,” October 25, 2013, https://press.un.org/en/2013/gadis3487.doc.htm.

[8] Ray Kaushik and William Selvamurthy, “Starlink’s Role in Ukraine: Portent of a Space War? | Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses,” Journal of Defence Studies 17, no. 1 (2023): 25–44.

[9] Gregory L. Schulte and Audrey M. Schaffer, “Enhancing Security by Promoting Responsible Behavior in Space,” Strategic Studies Quarterly 6, no. 1 (2012): 9–17.

[10] Thomas G. Robert, “Space Ports of The World,” Areport of the CSIS AEROSPACE SECURITY PROJECT, CSIS, March 2019, https://aerospace.csis.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/190313__SpaceportsOfTheWorld.pdf.

[11] Malcom Davis, “The coming of China’s Space Silk Road,” ASPI, The Strategist, August 11, 2017, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/coming-chinas-space-silk-road/.

[12] “NaVIC, India’s GPS, May Soon Get “Regional To Global” Changeover: ISRO,” NDTV, October 26, 2022, https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/navic-indias-gps-may-soon-get-regional-to-global-changeover-isro-chief-s-somanath-3463348.

[13] United Nations, “United Nations Resolution 1721(XVI). On International Cooperation in the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space,” 1961, https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties/resolutions/res_16_1721.html.

[14] Tereza Pultarova, “ How many satellites can we safely fit in Earth orbit,” SPACE.com, February 27, 2023, https://www.space.com/how-many-satellites-fit-safely-earth-orbit.

[15] UN.org, “Outer Space Increasingly ‘Congested, Contested and Competitive’, First Committee Told, as Speakers Urge Legally Binding Document to Prevent Its Militarisation | UN Press,” October 25, 2013, https://press.un.org/en/2013/gadis3487.doc.htm.

[16] Karim N Habibullah, “Some thoughts on Bangladesh’s first full-scale communication satellite,” The Daily Star, May 21, 2018, https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/some-thoughts-bangladeshs-first-full-scale-communication-satellite-1579194.

[17] NASA.com, “Orbital Debris,” 2021, https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/news/orbital_debris.html.

[18] Andrew May and Daisy Dobrijevic, “The Kármán Line: Where Does Space Begin?,” Space.com, November 13, 2022. https://www.space.com/karman-line-where-does-space-begin.

[19] United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea- Part VII, High Seas, https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/part7.htm.

[20] Unesco, With the “High Seas Treaty,” on biodiversity signed, what do we need to do next?, October 26, 2023, https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/high-seas-treaty-biodiversity-signed-what-do-we-need-do-next.

[21] Gbena Oduntan, Sovereignty and Jurisdiction in the Airspace and Outer Space: Legal Criteria for Spatial Delimitation, Routledge Research in International Law, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2012, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9780203807552.

[22] United Nations, United Nations Treaties and Principles on Outer Space, United Nations, 2002. https://www.unoosa.org/pdf/publications/STSPACE11E.pdf.

[23] Anna Fleck, “Who’s Responsible for Space Junk?,” Statista, September 22, 2022, Para., https://www.statista.com/chart/28309/countries-creating-the-most-space-debris/.

[24] Andrew Young, Christina Rogawski and Stefan Verhulst, “open Data’s Impact United States GPS System Creating a Global Public Utility,” January 2016, https://odimpact.org/files/case-studies-gps.pdf

[25] Sarah Sewall, Tyler Vandenberg and Kaj Malden, “China’s BeiDou: New Dimensions of Great Power Competition,” Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, February, 2023, https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/files/publication/Chinas-BeiDou_V10.pdf.

[26] John Xie, “China’s Rival to GPS Navigation Carriers Big Risk,” CHINA NEWS, Voice of America News, July 08, 2020, https://www.voanews.com/a/east-asia-pacific_voa-news-china_chinas-rival-gps-navigation-carries-big-risks/6192460.html.

[27] Press Information Bureau, Government of India, “Union Minister Dr. Jitendra Singh Says, ISRO Has Launched a Total of 129 Satellites of Indian Origin and 342 Foreign Satellites Belonging to 36 Countries since 1975,” last accessed October 19, 2023, https://pib.gov.in/pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1797196.

[28] Namrata Goswami, “Indian Space Program and Its Drivers: Possible Implications for the Global Space Market,” last accessed October 19, 2023, https://www.ifri.org/en/publications/notes-de-lifri/indian-space-program-and-its-drivers-possible-implications-global-space.

[29] Jeffrey Gettleman and Hari Kumar, “India Shot Down a Satellite, Modi Says, Shifting Balance of Power in Asia,” The New York Times, March 27, 2019, sec. World, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/27/world/asia/india-weather-satellite-missle.html.

[30] Simonetta Di Pippo, “Space Technology and the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda,” UN Chronicle, 3& 4 Vol. 2018, https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/space-technology-and-implementation-2030-agenda.

[31] Hussain, Mian Zahid, and Raja Qaiser Ahmed. “Space Programs of India and Pakistan: Military and Strategic Installations in Outer Space and Precarious Regional Strategic Stability.” Space Policy 47 (February 1, 2019): 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spacepol.2018.06.003.

[32] Ajay Lele, “Space Programs, Policies, and Diplomacy in South Asia,” In Routledge Handbook of the International Relations of South Asia, Routledge, 2022.

[33] Venkatasubramanian, K.V., “South Asian Satellite to Boost Regional Communication,” Press Information Bureau, Government of India, May 07, 2017, https://pib.gov.in/newsite/printrelease.aspx?relid=161611.

[34] Ananth Krisnan, “China’s home-grown Beidou satellite system eyes global footprint,” The Hindu, November 04, 2022, https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/chinas-home-grown-beidou-satellite-system-eyes-global-footprint/article66096031.ece

[35] Ajay Lele, “India Launches a South Asia Satellite,” The Space Review, 2017, last accessed October 21, 2023, https://thespacereview.com/article/3233/1.

[36] Shounak Set, “India’s Regional Diplomacy Reaches Outer Space,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2017, https://carnegieendowment.org/files/7-3-2017_Set_IndiaRegionalDiplomacy_Web.pdf.

[37] Farjana Sharmin, “Why South Asia needs regional cooperation on Space policy?,” November 08, 2022, South-South Research Initiative, https://www.ssrinitiative.org/why-south-asia-needs-regional-cooperation-on-space-policy/#:~:text=So%2C%20the%20regional%20countries%20need,people’s%20lives%20in%20South%20Asia.

[38] Gbenga Oduntan, Sovereignty and Jurisdiction in the Airspace and Outer Space: Legal Criteria for Spatial Delimitation, Routledge Research in International Law, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2012, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9780203807552; Alex Vines, “Africa in 2023: Continuing Political and Economic Volatility | Chatham House – International Affairs Think Tank,” January 09, 2023, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2023/01/africa-2023-continuing-political-and-economic-volatility; Arti Yadav and Badar Alam Iqbal, “Socioeconomic Scenario of South Asia: An Overview of Impacts of COVID-19,” South Asian Survey 28, no. 1 (March 1, 2021): 20–37, https://doi.org/10.1177/0971523121994441.

[39] ISSAfrica.org, “African Conflicts to Watch in 2022,” ISS Africa, 2021, https://issafrica.org/pscreport/psc-insights/african-conflicts-to-watch-in-2022.

[40] Stelios Michalopoulos and Elias Papaioannou, “Scramble For Africa And Its Legacy,” Palgrave Macmillan (ed.), The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2016, DOI 10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_3041-1.

[41] Samuel Oyewole, “The Quest for Space Capabilities and Military Security in Africa,” South African Journal of International Affairs 27, no. 2 (April 2, 2020): 147–72, https://doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2020.1782258, Also see, OBE Alex Vines, “Africa in 2023: Continuing political and economic volatility,” CHATHAM HOUSE, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2023/01/africa-2023-continuing-political-and-economic-volatility.

[42] Ayooluwa Adetola, “African Space Industry Annual Report 2023,” africannews.space, www.africannews.space/african-space-industry-annual-report-2023-edition/amp.

[43] Jevans Nyabiage, “China aims to lift Africa’s space ambitions in drive to beat US domination,” South China Morning Post, September 08, 2022, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3191714/china-aims-lift-africas-space-ambitions-drive-beat-us.

[44] Kate Barlett, “Why China, African Nations Are Cooperating in Space,” September 13, 2022, Voice of America News, https://www.voanews.com/a/why-china-african-nations-are-cooperating-in-space/6745595.html.

[45] Sarah Sewall, Tyler Vandenberg and Kaj Malden, “China’s BeiDou: New Dimensions of Great Power Competition,” Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, February, 2023, https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/files/publication/Chinas-BeiDou_V10.pdf.

[46] Giovanni Faleg, ed. African Spaces: The New Geopolitcal Frontlines, Chaillot Paper 173, European Union Institute for Security Studies, 2022, https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/CP_173_0.pdf; Also, Josephat Juma, “Africa and geopolitical competition,” THE INDEPENDENT, December 29, 2022, https://www.independent.co.ug/africa-and-geopolitical-competition/

[47] Rose Croshier, “Opportunities for US–Africa Space Cooperation and Development,” Policy Paper, CGD Policy Paper, Center for Global Development, 2022, https://www.cgdev.org/publication/opportunities-us-africa-space-cooperation-and-development.; also Julie Michelle Klinger, “A Brief History of Outer Space Cooperation Between Latin America and China.” Journal of Latin American Geography 17, no. 2 (2018): 46–83.

[48] Óscar Garrido Guijarro, A common African outer space policy to meet the continent’s challenges, Analysis Paper, IEEE Analysis Paper, 2022, https://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_analisis/2022/DIEEEA73_2022_OSCGAR_Espacio_ ENG.pdf

[49] African Union, “African Space Strategy for Social, Political and Economic Integration,” 2019, https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/37434-doc-au_space_strategy_isbn-electronic.pdf.

[50] African Union, African Space Policy, Second Ordinary Session For the specialised Technical Committee Meeting on Education, Science and Technology, 2017, https://au.int/sites/default/files/newsevents/workingdocuments/33178-wd-african_space_policy_-_st20444_e_original.pdf.

[51] Amna Kalhoro, “Space 2.0: Developing Nations Lead the Race for the Final Frontier,” Space 2.0: Developing nations lead the race for the final frontier, last accessed October 19, 2023, https://www.trtworld.com/opinion/space-2-0-developing-nations-lead-the-race-for-the-final-frontier-65711.

[52] APSCO, “About APSCO,” last accessed October 19, 2023, http://www.apsco.int/html/comp1/content/WhatisAPSCO/2018-06-06/33-144-1.shtml.

[53] APRSAF, “About APRSAF | Asia-Pacific Regional Space Agency Forum,” last accessed October 19, 2023, https://www.aprsaf.org/about/.

[54] Sheila A. Smith “The Quad in the Indo-Pacific: What to Know,” COUNCIL on FOREIGN RELATIONS, May 27, 2021, https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/quad-indo-pacific-wha.

[55] Press Information Bureau, Government of India, “Cabinet Approves Memorandum of Association (MoA) by India for Establishment of BIMSTEC Technology Transfer Centre at Colombo, Sri Lanka,” last accessed October 19, 2023, https://pib.gov.in/pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1833814.