Abstract: We can reconceptualise warfare by contrasting Clausewitz with the modern practice of cognitive warfare, as evidenced by Ukraine’s defence methodologies. The strategic orchestration of ‘infopolitik’ and the sophisticated use of social media can shape narratives and public perception. This article revisits Clausewitz’s tenet of war as a political instrument and juxtaposes it with contemporary conflict’s multidimensional tactics. By scrutinising Ukraine’s digital and psychological warfare tactics, one may question the applicability of Clausewitz’s framework, seeking to understand if these novel dimensions of warfare compel a redefinition or an expansion of his thesis to navigate the complexities of contemporary geopolitical confrontations.

Problem statement: How can concepts such as ‘people’s war,’ ‘whole of society approach,’ and the strategic triad of ‘ends, ways, means’ be applied in Ukraine’s defence mechanisms?

Bottom-line-up-front: The Ukrainian government’s use of social media and digital platforms to rally national and international support is a testament to this. Appeals and narratives shared online serve not only to unite the Ukrainian populace but also to draw global attention and empathy, effectively using emotional engagement as a strategic tool in their cognitive warfare arsenal.

So what?: Scholars should approach a reevaluation of Clausewitz in the light of Waltzian first-level analysis. Scholars should probe the individual decisions and perceptions that shape state behaviour in a cognitive context. This evolution demands that modern policy and strategy formulation explicitly integrate cognitive considerations, bridging the divide between traditional military strategy and the psychological dimensions of conflict.

A Classic Theory of War?

The nature of warfare has expanded beyond traditional, geographically defined battlefields to encompass the cognitive and digital spheres, where public perception and opinion form a critical front. In this evolved landscape, the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence (UMOD) strategically employs state messaging through online social platforms, engaging hearts and minds globally and transcending geographical boundaries. This shift poses a fundamental question: In an era where digital and cognitive strategies are integral to warfare, does Carl von Clausewitz’s classic theory, which views war as a tool of politics, still hold ground?[1]

The Ukraine Ministry of Defence has adeptly integrated cognitive warfare into its broader military strategy. This approach, which utilises information and psychological operations to influence perceptions and decision-making, significantly enhances traditional military and political strategy frameworks.[2] While the Ukrainian strategy includes the innovative use of ‘infopolitik’ and social media, it remains grounded in the fundamental need for conventional military resources, epitomised by President Zelenskyy’s statement, ‘I need ammunition, not a ride.’ This blend of traditional and modern tactics invites a reevaluation of Clausewitz’s principles, acknowledging the continued importance of physical military strength while recognising the growing role of cognitive strategies in contemporary warfare.[3]

The Ukraine Ministry of Defence has adeptly integrated cognitive warfare into its broader military strategy.

A philosophical reevaluation has become essential with the emergence of information and cyber warfare.[4] The significance of the UMOD’s strategies in cognitive warfare lies in their unique blend of classical military tactics and contemporary digital methodologies. This blend offers a compelling case study for examining the application of traditional military theories in the context of modern, technology-driven conflict.

The UMOD’s approach is not merely an addition to the conventional warfare toolkit; it represents a nuanced adaptation of these theories to the realities of the digital age. By analysing how the UMOD integrates cognitive warfare strategies with traditional military operations, we gain valuable insights into the evolving nature of conflict and the potential need to adapt classical military theories to remain relevant in today’s rapidly changing technological and geopolitical landscape. This case study is significant because it challenges us to reconsider and potentially refine our understanding of warfare in the digital era, ensuring that our theoretical frameworks are robust and adaptable enough to guide contemporary military strategies effectively.

“However much pains may be taken to combine the soldier and the citizen in one and the same individual, whatever may be done to nationalise wars”

Clausewitz[5]

The profound insight from Yaroslav Honchar, “We are like a hive of bees. One bee is nothing, but a thousand can defeat a big force,” eloquently captures the essence of Ukraine’s unification and resistance in the Battle of Kyiv and its cognitive warfare against a formidable adversary.[6] This metaphor resonates deeply with Clausewitzian tenets, particularly the ‘whole of society’ approach. It underscores the collective strength and unity required in warfare. In this digital era, Clausewitz’s theory finds renewed significance in Ukraine’s adept manipulation of narrative and information to influence public opinion and political decisions.

Clausewitz’s Enduring Theory: A Lens for Modern Cognitive Warfare

Clausewitz’s “On War” is a cornerstone in the study of military strategy. Clausewitz articulates war as a complex instrument of policy that compels an adversary to accede to one’s aims through the application of force.[7] In this discourse, Clausewitz distinguishes between ‘real war,’ the actual wars experienced with their inherent disorder and unpredictability, and ‘absolute war,’ an idealised version of war conducted with maximum violence and without the constraints of politics or society. This distinction is critical, as the objectives of cognitive warfare, which aim to modify perceptions and influence thought processes, align more closely with the characteristics of ‘real war.'[8]

The critique of Clausewitz by Holmes opens the door for a broader discussion of the contemporary applicability and limitations of Clausewitz’s theories. Contemporary case studies will illustrate the application of Clausewitz’s theories to current conflicts, highlighting how they inform strategies in the cognitive and digital realms.[9]

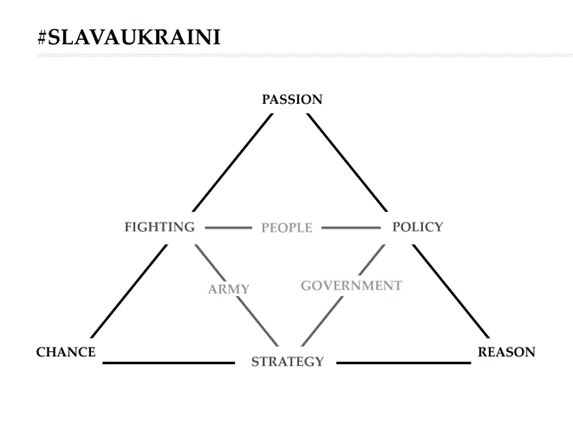

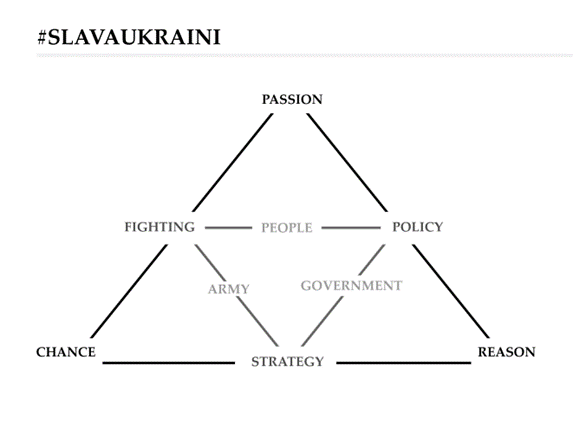

Clausewitz’s ‘wondrous trinity’—the confluence of violence, chance, and reason—presents a resonant framework for dissecting cognitive warfare.[10] The element of violence, while traditionally understood in physical terms, transmutes in the cognitive domain into aggressive tactics that assault perceptions and beliefs. Chance, representing the unpredictability and fluidity of war, finds its parallel in the ever-shifting digital landscape where disinformation and psychological operations create a nebulous battleground. Finally, reason, the element that governs and directs violence within the context of war’s political nature, is mirrored in the strategic deployment of narratives and the calculated manipulation of public opinion to achieve political ends.[11]

Clausewitz’s ‘wondrous trinity’—the confluence of violence, chance, and reason—presents a resonant framework for dissecting cognitive warfare.

This tripartite lens, originally conceptualised to understand the dynamics of kinetic warfare, thus provides an insightful perspective for evaluating the complex interactions of strategic elements in cognitive warfare, where the mind is the battlefield, and information is the weapon.

Furthermore, the analysis conducted on Clausewitz’s examination of “small wars” and asymmetric warfare provides a valuable perspective for comprehending cognitive warfare.[12] Cognitive warfare frequently involves non-state actors, manifesting asymmetric conflict when the battlefronts mostly revolve around perceptions and influence.[13] While Clausewitz’s general theory presents a framework for understanding large-scale conflicts, it is in the granularity of ‘small wars’ and asymmetric engagements where the true adaptability of his ‘wondrous trinity’ becomes apparent—especially when viewed through the lens of modern cognitive warfare strategies. The viewpoint expressed here is supported by Scheipers'[14] and Heuser’s[15] work, which delves into the concepts of “small wars” and “people’s war,” as outlined by Clausewitz. These authors highlight the interconnectedness of emotions and rationality in these notions.

Time As A Dimension of Warfare: Clausewitz to the Present

While Clausewitz’s insights into the nature of war as a political instrument remain relevant, the dynamics of information exchange in the digital era have introduced a new dimension to warfare: the immediacy of tactical actions. McIntosh’s emphasis on the ‘primacy of the present’ in contemporary warfare strategies highlights the significance of real-time information dissemination, which can have immediate tactical implications.[16] However, as Griffin and Kaldor’s analysis of the Afghanistan conflict suggests, while the nature of violence as an instrument of policy persists, its strategic impact unfolds over time, often independent of the immediate tactical victories or setbacks.

While Clausewitz’s insights into the nature of war as a political instrument remain relevant, the dynamics of information exchange in the digital era have introduced a new dimension to warfare.

In the context of Ukraine, high-profile events like the sinking of the Moskva illustrate the tactical immediacy enabled by cognitive warfare. This event, while significant in the moment, may not immediately alter the broader strategic landscape. This distinction underscores the need for an updated critique of Clausewitzian theory, one that recognises the nuanced interplay between the instantaneous nature of modern conflict and the gradual unfolding of strategic outcomes.[17] In this era of cognitive warfare, it is crucial to differentiate between the immediate tactical advantages gained through rapid information dissemination and the longer-term strategic effects that continue to be shaped by traditional military engagements.[18]

Ukraine’s Cognitive Warfare Tactics: Extending Clausewitz’ Battlefield

The transition from Carl von Clausewitz’s concept of physical battlefields to the abstract realms of cognitive warfare marks a profound evolution like conflict. This shift is embodied in Ukraine’s approach to Russia’s war in Ukraine, where the immediacy of weaponised information has become critical.[19] The proliferation of digital technologies and social media platforms has not only further transformed the medium of conflict but also accelerated its pace, significantly impacting the dynamics of modern warfare.[20]

The exploration of endogenous military strategy and crisis bargaining highlights how contemporary conflicts engage multiple layers of society and politics, extending beyond the traditional battlefield.[21] In this complex tapestry, the cognitive aspect of warfare gains prominence, leveraging information as a strategic asset. Analysis of public diplomacy and non-state actors further enriches this perspective, demonstrating how non-traditional actors have become crucial in shaping public opinion and national narratives.[22] Operating within and beyond national borders, these actors contribute to a broader and more dynamic battlefield.[23]

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s engagement with the public through his “100 speeches in 100 days of war” exemplifies the fusion of leadership, communication, and strategy in cognitive warfare.[24] Zelenskyy’s approach underscores the importance of maintaining public morale and international support, illustrating how the cognitive dimension of warfare can be as critical as the physical one.[25]

This evolution aligns with Clausewitzian principles in its emphasis on the ‘fog of war’ and the unpredictability of conflict. However, it also necessitates a reevaluation of these principles in the context of the information age. The cognitive battlefield is not constrained by geography; it is omnipresent. It is mainly fought in the digital sphere, where perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes are as strategically significant as physical territories. The Ukrainian experience illustrates this new paradigm: information and psychological operations are integral to national defence strategies.

The cognitive battlefield is not constrained by geography; it is omnipresent.

In this new form of warfare, the speed at which information is disseminated and manipulated can have immediate and far-reaching effects on conflict’s physical and psychological aspects.[26] Propaganda, psychological tactics, and the strategic use of information have become potent weapons. The power of these tools lies not only in their ability to influence public opinion but also in their capacity to shape international perceptions and policy decisions.

The extension of Clausewitz’s battlefield into the cognitive domain reflects a significant evolution in military strategy. It underscores the need for a holistic approach to conflict, considering the power of information and public perception as critical components of modern warfare. This adaptation of Clausewitzian thought to contemporary realities suggests that the mastery of information and narrative may be as decisive in the outcome of conflicts as traditional military prowess.

Clausewitzian Theory in the Face of Cignitive Challenges

In examining the adaptability of Clausewitz’s theoretical framework to the nuanced cognitive battles of 21st-century warfare, we focus on specific elements of his theory that intersect with modern conflict dynamics. Clausewitz’s concept of the ‘fog of war,’ traditionally understood as the uncertainty in situational awareness experienced by participants in military operations, finds a contemporary parallel in the pervasive disinformation and psychological manipulation that characterise cognitive warfare. This modern ‘fog’ creates a disorienting haze on physical battlefields and in public opinion and morale.[27]

The war in Ukraine vividly illustrates this phenomenon. Here, the struggle transcends traditional territorial defence, extending into the cognitive domain where narrative control becomes a pivotal battleground. This aspect of the conflict reflects a clear adaptation of Clausewitzian principles, where the ‘fog of war’ is no longer just a physical barrier but also a psychological and informational one. The Ukrainian response, leveraging both military strategy and narrative control through media and information channels, demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of this modern interpretation of Clausewitz’s ideas.[28] Thus, our examination centres on how these principles, rooted in 19th-century military thought, remain relevant and adaptable to the complexities of modern cognitive warfare.

Clausewitz and Cognitive Warfare

Within the Clausewitzian paradigm, war is conceptualised as an extension of political engagement, utilising force to bring an adversary to submission. This principle acquires fresh relevance in cognitive warfare, where the tools of conflict extend beyond physical force to encompass the strategic manipulation of information and perceptions. This form of conflict transcends physical confrontations, targeting the minds and perceptions of populations to achieve strategic objectives. Cognitive warfare, as manifested in the tactics employed by Russia post-Crimea’s annexation and throughout Russia’s war in Ukraine, represents an evolution of Clausewitzian thought. It operates on the principle of nonlinearity that Clausewitz postulated, aiming not just to alter the physical state of play but to reshape the cognitive landscapes of adversaries, thus influencing their decisions and undermining societal cohesion. Scholars have offered diverse definitions of cognitive warfare. Yet, a common thread in these definitions is the focus on manipulating public opinion and destabilising institutions. This emphasis aligns with Clausewitz’s understanding of war as a complex and multifaceted phenomenon.[29]

Cognitive warfare, as manifested in the tactics employed by Russia post-Crimea’s annexation and throughout Russia’s war in Ukraine, represents an evolution of Clausewitzian thought.

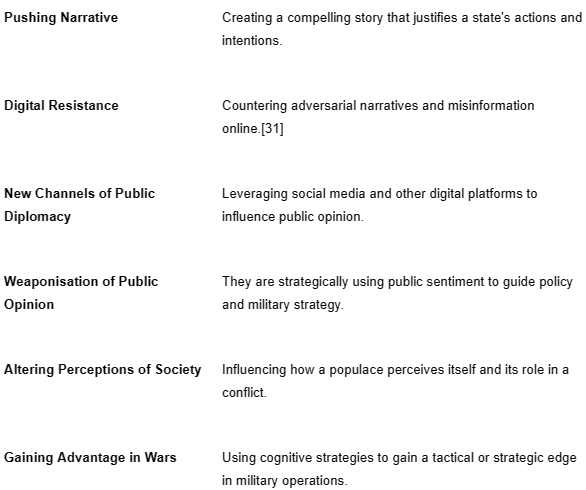

In the landscape of modern conflict, the enduring influence of Clausewitz is evident in strategies that increasingly prioritise psychological elements over kinetic actions. This shift from Clausewitz’s era to our current age is significantly driven by the global availability of social media and the rapid velocity at which the internet can disseminate information. These digital platforms have transformed information and perception into critical territories of contestation. The widespread reach and instantaneous nature of online communication have elevated these aspects, making them central to the strategies and outcomes of contemporary conflicts. In this context, understanding the nuances of Clausewitz’s principles in relation to these modern dynamics becomes crucial.[30] While Clausewitz’s framework laid the foundational principles of warfare, the digital era has introduced new dimensions to this domain. These can be encapsulated in what we identify as the six facets of cognitive warfare.

The Six Facets of Cognitive Warfare

Cognitive warfare is not a monolithic construct but consists of various interconnected components. These six facets of cognitive warfare, each with distinct implications, necessitate a revised approach to traditional military strategy, drawing from Clausewitz’s legacy but expanding its horizons.

The complexity of these six facets illustrates the multifaceted nature of cognitive warfare, requiring a nuanced approach that goes beyond traditional military doctrines.

Clausewitz, Cognitive Warfare, and the Modern Battlefield

The human mind serves as the primary battlefield in cognitive warfare. The objective extends beyond altering perceptions; it aims to shift how individuals think and act fundamentally. When executed effectively, this warfare can reshape societal beliefs and behaviours to align with the aggressor’s objectives.[32] In its most extreme manifestation, it can disintegrate societies to the point where collective resistance becomes infeasible.[33]

Since Russia’s invasion in February 2022, the conflict’s narrative has evolved significantly, especially in Russian President Vladimir Putin’s rhetoric. Initially, Putin justified the invasion with claims of ‘denazifying’ Ukraine, aiming to rally domestic support. However, as Russian military setbacks occurred, the narrative shifted to framing the conflict as a geopolitical struggle against NATO and the U.S., accusing the West of fuelling the war.[34]

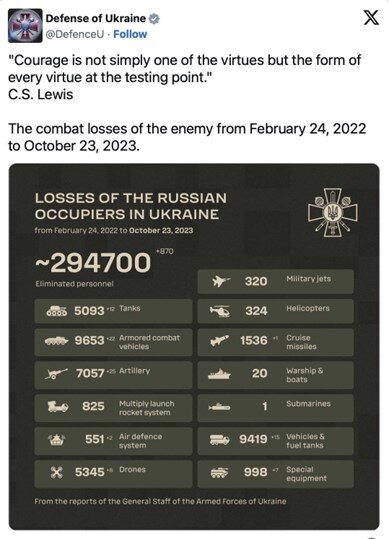

Internationally, Putin has employed a mix of hard-line nationalism and appeals to global values, seeking to maintain domestic support and justify the invasion. In contrast, Ukraine’s strategic use of infopolitik has effectively countered Russia’s narrative, leveraging social media to gain global support. Ukraine’s focus on moral dimensions and Russian losses has been pivotal in shaping global perceptions despite the challenges posed by shifting global attention and the persistence of Russian narratives through platforms like Telegram.

Ukraine’s strategic use of infopolitik has effectively countered Russia’s narrative, leveraging social media to gain global support.

The contrasting approaches of Russia and Ukraine highlight the critical role of strategic communication in modern conflicts. Despite the fluid nature of global attention and the Russian media’s presence in the digital space, Ukraine’s success in narrative control underscores the importance of adaptive information warfare strategies in shaping public opinion and international support.

This scenario necessitates a reevaluation of Clausewitz’s theories, particularly considering the urgent need to adapt to the immediacy with which information impacts public perception and morale. The Clausewitzian concept of “time as a dimension” in warfare takes on new significance in this digital age. The rapid dissemination of information and the ability to sustain a consistent and motivating narrative have become pivotal in shaping the course of conflicts. The accelerated pace of information flow in cognitive warfare requires strategies that can respond in real-time, adapting to the fluid nature of public opinion and perception.[35]

Moreover, Clausewitz’s ‘wondrous trinity’ offers an insightful perspective for evaluating the strategic elements in cognitive warfare. The battlefield has evolved from physical terrain to the human mind, with information as the primary weapon. In this context, the ‘trinity’ elements of violence, chance, and reason manifest in aggressive information campaigns, the unpredictability of social media virality, and the strategic use of narratives, respectively.[36]

In Ukraine’s case, the application of these updated Clausewitzian principles is evident in their approach to narrative warfare. By focusing on the moral dimensions of the conflict — the hearts and minds of both their citizens and the international community — and consistently publicising the enemy’s losses, Ukraine counters Russian propaganda. It solidifies its stance in the cognitive domain of warfare.[37]

Cognitive warfare can be both tactical and strategic. Tactical campaigns may target specific military operations or influence public policy in the short term. Strategic campaigns, on the other hand, aim to destabilise societies or alliances over extended periods by eroding governance, subverting democratic processes, and inciting civil unrest or separatist movements.

Clausewitz’s theories offer a valuable framework for understanding the challenges of cognitive warfare. According to Clausewitz, tactics aim for battlefield victories, while strategy leverages those victories to achieve broader war objectives. This framework, encapsulated in the modern concept of ends, ways, and means, remains pertinent in cognitive warfare. The means (information sovereignty) must align with the ends (strategic or tactical objectives), highlighting the necessity of a unified approach to countering cognitive warfare threats.[38]

Western governments must recognise that mitigating the impact of Russian cognitive warfare is a long-term endeavour. Addressing this issue requires sustained, multi-decade efforts.

Western governments must recognise that mitigating the impact of Russian cognitive warfare is a long-term endeavour.

Cognitive Warfare: Definitions and Implications in Infopolitik

Cognitive warfare represents a nuanced conflict where information, psychology, and technology intertwine to manipulate perceptions and sway decision-making processes. This sophisticated strategy employs a variety of tactics aimed at sculpting beliefs and behaviours to achieve strategic objectives. Infopolitik emerges as a pivotal component, purposefully moulding public opinion and political narratives to further national interests.

Lasswell’s foundational work in communication and propaganda studies offers critical insights into the psychological facets of such warfare. Lasswell’s examination in “Propaganda Technique in the World War” sheds light on the utilisation and efficacy of propaganda during the First World War, highlighting key methods of mass persuasion. His exploration goes deeper in “Power and Personality“, where the relationships between power dynamics and individual psychology are dissected, elucidating how power influences public opinion and behaviour.[39] Further expanding on this theme, “The Structure and Function of Communication in Society” delves into communication’s varied roles and impacts within societal constructs.[40] Lasswell’s analyses in these works provide a historical lens through which the strategic use of information in cognitive warfare can be understood, emphasising the sustained importance of propaganda and communication strategies in contemporary conflict settings. This historical perspective enriches our understanding of modern psychological operations. It underscores the continuity and evolution of strategic communication in warfare.

In the complex arena of international relations, Russia’s war in Ukraine presents a crucial case study for understanding the contemporary dynamics of cognitive warfare through the lens of Clausewitzian theory. Clausewitz’s idea of war as an extension of political objectives takes on a unique form in the digital era. In this context, states strategically utilise social media platforms during political crises, transforming these digital spaces into arenas for narrative shaping and manipulation.[41] Such tactics are increasingly employed to influence public opinion worldwide, reflecting a modern adaptation of Clausewitz’s theories.[42] This phenomenon underscores the intricate dynamics of infopolitik in the digital era, intertwining public diplomacy, strategic storytelling, and propaganda in a manner reflective of Clausewitz’s principles.

In the complex arena of international relations, Russia’s war in Ukraine presents a crucial case study for understanding the contemporary dynamics of cognitive warfare through the lens of Clausewitzian theory.

This modern conflict scenario necessitates a reevaluation of Clausewitz’s theories, particularly considering the urgent need to adapt to the immediacy with which information impacts public perception and morale.

Digital Diplomacy: A Tool for Cognitive Influence

As we delve deeper into the nuances of cognitive warfare, it becomes evident that digital diplomacy is a pivotal component in modern statecraft.[43] This digital dimension encompasses a spectrum of tactics that influence international relations and advance foreign policy objectives.[44] These tactics include but are not limited to:

- Infopolitik: The strategic use of information by states to support foreign policy aims and influence international affairs;[45]

- Strategic Narrative: A tool political actors use to construct a shared meaning of the past, present, and future of international politics to shape the behaviour of domestic and international actors. It is a means through which actors aim to assert their power, not by military might or economic coercion, but through the compelling power of ideas and the ability to shape perceptions and discourses;[46]

- Narrative Washing: The selective shaping of narratives to present a biased view of reality, aiming to misguide public opinion and shift focus from problematic issues;[47]

- Narrative Laundering: Disseminating disinformation through seemingly credible sources to fabricate legitimacy and embed false narratives; and[48]

- Propaganda: The distribution of slanted or misleading information intended to manipulate public sentiment and control the cognitive battleground.[49]

As this exploration of digital diplomacy and cognitive warfare concludes, it is crucial to recognise the complex ethical terrain states must navigate.[50] Each component, from Infopolitik to propaganda, carries the potential for a significant impact on global public opinion and international affairs. The ethical implications and risks of backlash from international adversaries and domestic audiences are paramount in these practices. This intricate balance of power, information, and ethics in cognitive warfare underscores the evolving nature of international diplomacy in the digital age, and global adversaries and domestic populations scrutinise cognitive warfare practices.[51]

The Literature Review

This exploration of Clausewitz in the context of cognitive warfare lays the foundation for a deeper examination of tactics like Infopolitik, revealing the intricate interplay between traditional military strategies and modern information conflicts. The literature review uncovers a complex landscape of interpretations, applications, and critiques of Clausewitzian theory, highlighting its multifaceted relevance in the modern era of cognitive warfare.

The Ukrainian Ministry of Defence’s (UMOD) strategic choice of X (formerly known as Twitter) for disseminating communications is a multifaceted decision deeply rooted in modern warfare and geopolitical strategy dynamics. X’s global reach and influence make it an ideal platform for Ukraine to engage with international audiences, crucial in a conflict where global public opinion and international support play pivotal roles. This platform’s real-time nature is particularly suited to the fast-paced environment of contemporary conflicts, allowing for the rapid dissemination of information and timely updates, which is essential in cognitive warfare. Additionally, the UMOD’s preference for English in their X communications aligns with President Zelenskyy’s initiative to recognise English as an official language in Ukraine. This strategic use of English is not just about broadening communication channels; it’s a deliberate effort to align Ukraine more closely with Western institutions and standards, reflecting a nuanced understanding of the psychological dimensions of warfare as conceptualised by Clausewitz.

The Ukrainian Ministry of Defence’s strategic choice of X for disseminating communications is a multifaceted decision deeply rooted in modern warfare and geopolitical strategy dynamics.

Moreover, X is a critical platform for direct engagement with journalists, diplomats, and international organisations, enabling the UMOD to shape narratives and effectively foster support for Ukraine’s position. The structure of X facilitates the viral spread of information, allowing strategic messaging by the UMOD to quickly gain traction and be amplified across various networks, thereby extending the reach and impact of their narratives. This approach is crucial in counteracting misinformation and presenting Ukraine’s perspective on the conflict, contributing significantly to the broader cognitive warfare strategy. In essence, the UMOD’s use of X, especially with content in English, is a calculated move that underscores the importance of strategic communication in contemporary conflicts. Platforms like X have become critical tools in the battle for narrative control and public diplomacy, thus reflecting a modern interpretation of Clausewitz’s emphasis on the psychological over the kinetic in warfare.

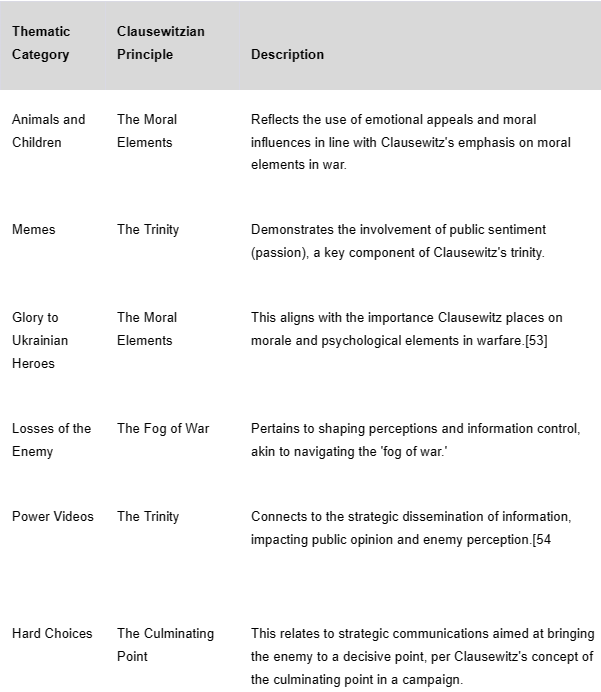

Ukrainian Ministry of Defence: A Focused Case

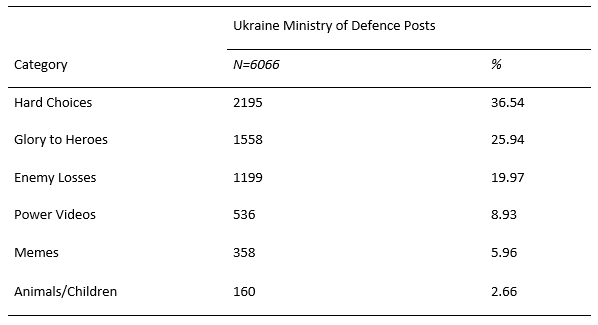

Utilising advanced qualitative coding techniques augmented by NLP, the study categorised the Ministry’s posts into six thematic areas: ‘Memes,’ ‘Animals and Children,’ ‘Glory to the Heroes,’ ‘Hard Choices,’ ‘Losses of the Enemy,’ and ‘Power Videos.’ These categories were selected to reflect the diverse aspects of the Ministry’s communication strategy, ranging from the emotionally charged ‘Animals and Children’ to the more strategically oriented ‘Hard Choices’ and ‘Losses of the Enemy.’ The coding was descriptive and analytical, seeking to uncover the deeper connotations of these posts in the context of Clausewitzian principles, such as the fog of war, the Trinity, the Culminating Point, and the Moral Elements.[52]

Utilising advanced qualitative coding techniques augmented by NLP, the study categorised the Ministry’s posts into six thematic areas: ‘Memes,’ ‘Animals and Children,’ ‘Glory to the Heroes,’ ‘Hard Choices,’ ‘Losses of the Enemy,’ and ‘Power Videos.’

The NLP techniques employed were intricately designed to discern the nuances of language, capturing how the Ministry addressed the ‘Moral Elements’ of warfare, where shaping public sentiment can be as decisive as military engagements. By quantifying the prevalence of themes and interpreting their contextual significance, the research aimed to shed light on the Ministry’s sophisticated use of X as a conduit for national defence narratives and international diplomatic discourse.

This study examines the alignment or divergence of the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence’s (UMOD) X communications with Carl von Clausewitz’s classical understanding of war. Employing a mixed-methods approach, it categorises and interprets prevalent themes within these communications.

Data Collection

The dataset comprises original posts from the UMOD’s official X account from November 23, 2021, to October 29, 2023. A Python script utilising X’s API selectively extracted content and metadata, focusing on original posts and excluding quote posts, reposts, and engagement metrics to maintain data integrity.

Qualitative Coding

The qualitative analysis involved systematically coding content into thematic areas, reflecting underlying messages and intentions. These areas include:

- Glory to Ukrainian Heroes: Posts honouring the Ukrainian military and civilians, emphasising heroism and resilience.

- Memes: Visual content, particularly memes, analysed for their use of humour, satire, or poignant imagery.

- Hard Choices for the Enemy: Content suggesting strategic manoeuvres or decisions challenging adversaries.

- Enemy Losses: Posts reporting or referencing enemy forces’ losses, capturing informational tactics in warfare.

- Children, Animals: Posts featuring children and animals, highlighting the human impact of conflict.

- Power Videos: Video content, whether official updates or compelling frontline footage, analysed for message impact and narrative role.

The coding process aligned with the study’s theoretical framework, enabling a grounded analysis of the UMOD’s digital communication strategies.

Categorical Counts and Percentages

Each post was quantitatively assessed and categorised, providing a statistical overview of the thematic emphasis in the UMOD’s X communication. This approach juxtaposed qualitative thematic richness with quantitative precision, enabling a comprehensive analysis.

Ethical Considerations and Limitations

The study adhered to ethical standards, analysing publicly accessible posts. It recognised potential biases in theme selection and interpretation and the challenges in conveying tone and sentiment in digital communication.

Expected Outcomes

The study aims to dissect the thematic content and emotional undertones of the UMOD’s posts, contributing insights into digital communication strategies within geopolitical contexts. It seeks to illustrate how a national defence entity leverages social media in national security and public diplomacy, emphasising strategic information dissemination in modern warfare.

Data and Findings

Data and findings present a detailed analysis of the data collected from the official X account of the UMOD, offering a comprehensive view of their strategic communication tactics from November 23, 2021, to October 29, 2023. The following table categorises 6,066 posts into distinct thematic areas, encapsulating the diverse and multifaceted narrative pursued by the UMOD.

Key Findings and Alignment with Clausewitzian Concepts

The Culminating Point in Strategic Communication: ‘Hard Choices’

The ‘Hard Choices’ category, the most dominant theme in the dataset, includes 2,195 posts, accounting for 36.54% of the total. This prevalence underscores its pivotal role in the UMOD’s strategic communication. These posts mirror Clausewitz’s concept of the culminating point in military strategy, focusing on critical and strategic decision-making moments within the campaign. They reflect the complex and often challenging choices the Ministry faces, highlighting the gravity and significance of such decisions.

This emphasis on ‘Hard Choices’ indicates the Ministry’s approach to pivotal moments in military strategy and communicates the weight of these decisions to a broader audience, thereby aligning with the concept of reaching a decisive point in a campaign as articulated by Clausewitz.

The Moral Elements in Celebrating Bravery: ‘Glory to Ukrainian Heroes’

In the dataset, the ‘Glory to the Heroes’ category, comprising 1,558 posts or 25.94% of the total, emphasises the moral elements in warfare, as conceptualised by Clausewitz. This substantial portion of the UMOD’s communication strategy celebrates heroism and valour. By highlighting acts of bravery, these posts play a crucial role in bolstering morale and accentuating the human aspects of conflict.

This alignment with Clausewitz’s psychological elements in warfare underscores the importance of moral strength and the spirit of resilience in the face of adversity, reflecting a strategic approach to uphold and inspire both military and civilian audiences.

Insight into the Fog of War

The ‘Losses of the Enemy’ category, comprising 1,199 (19.97%) posts, is crucial in the department’s communication strategy. The Ministry’s infopolitik cuts through the ‘fog of war’ by providing insights into the operational aspects of the conflict, offering a transparent view of battlefield successes and challenges.

Harnessing the Clausewitzian Trinity in Digital Warfare Communication

The strategic use of diverse content categories by the UMOD, such as ‘Power Videos’ (8.93%) and ‘Memes’ (5.96%), exemplifies an intricate application of Clausewitz’s ‘trinity’ concept in modern digital communications. This range of content, particularly visually-driven mediums like ‘Power Videos’ and ‘Memes,’ signifies a profound understanding of the ‘Hearts and Minds’ aspect of warfare. It suggests a comprehensive approach to engaging a broad audience, humanising the defence narrative, and enhancing the propagation of key messages in the digital space.

The strategic use of diverse content categories by the UMOD, such as ‘Power Videos’ (8.93%) and ‘Memes’ (5.96%), exemplifies an intricate application of Clausewitz’s ‘trinity’ concept in modern digital communications.

By integrating various forms of media, the Ministry demonstrates its adeptness in balancing the complex interplay of emotions, reason, and chance that characterise Clausewitz’s trinity. This approach ensures a more dynamic and relatable communication strategy. It aligns with the digital era’s evolving public engagement and perception nature. Such diverse and engaging content underscores a nuanced strategy to inform, resonate with, and mobilise public sentiment, reflecting a deep understanding of contemporary conflict communication’s psychological and emotional dimensions.

Quantitative Findings of Clausewitzian Principles

The qualitative coding process involved meticulously examining each post to ensure accuracy and reliability in categorising them into the respective themes. These findings serve as a foundation for a deeper understanding of the UMOD’s communication strategy and its resonance with established military and strategic concepts.

Prospects for Clausewitzian Theory Amidst Cognitive Warfare Dynamics

The robustness of Clausewitz’s doctrine is tested by the advent of cognitive warfare, where the integration of information, psychology, and technology reshapes the battlefield. This shift from kinetic clashes to manipulating perceptions and narratives requires a nuanced understanding of war—a concept that Clausewitz, in his prescience, captured through the metaphor of the ‘fog of war.’ The contemporary parallel lies in informational sovereignty, akin to controlling the high ground in earlier strategic doctrines.

In Ukraine, the dynamics of cognitive warfare resonate with Clausewitz’s conception of war as a political tool. Here, the strategic deployment of information and crafting of national narratives manifest as modern-day extensions of Clausewitz’s ‘war by other means’, reinforcing the notion that the political object remains the sine qua non of conflict.

The impact of social media and digital platforms on warfare demands a reconceptualisation akin to the shifts that occurred with the advent of new military technologies in the past. It represents the latest iteration of the ‘wondrous trinity’—the intermingling of chance, reason, and passion that Clausewitz deemed integral to the nature of war.

Validity of Clausewitz’s Theory in Digital and Cognitive Warfare

Turning the focus to the UMOD’s digital strategies offers practical insights into how Clausewitz’s conceptualisation of war as a political tool manifests in today’s digital battlefield:

- Clausewitz’s Theory as a Political Instrument in Digital Warfare. Clausewitz’s fundamental assertion that war is an extension of politics is evident in the digital communication strategies of the UMOD. The department’s posts, particularly in categories like ‘Hard Choices’ and ‘Glory to Ukrainian Heroes,’ illustrate this concept. These posts communicate strategic military decisions and align them with the country’s broader political goals, demonstrating Clausewitz’s theory’s relevance in the digital age;

- Transformation of Clausewitz’s Concepts in the Digital Era. Adapting Clausewitz’s concepts, such as the ‘fog of war,’ to the digital realm is critical to modern warfare. The UMOD’s approach to providing clear and consistent information amidst the chaotic and fast-paced digital landscape aligns with Clausewitz’s emphasis on the pivotal role of information in warfare;

- Emotional and Psychological Warfare Tactics. Reflecting Clausewitz’s recognition of war’s emotional and moral dimensions, the UMOD uses digital platforms to engage public sentiment. Categories like ‘Memes’ and ‘Animals/Children’ demonstrate the strategic use of emotional and psychological elements to maintain public morale and support;

- Utilising Information as a Tactical and Strategic Tool. The strategic dissemination of information via the UMOD’s X account aligns with Clausewitzian principles of tactics and strategy. Categories such as ‘Power Videos’ and updates on enemy losses demonstrate the tactical use of information to support broader strategic objectives in cognitive warfare.

Concluding Observations

The exploration of UMOD’s digital communication strategies confirms Clausewitz’s enduring relevance, particularly his view of war as a political tool in the digital age. Strategic military decisions, exemplified by ‘Hard Choices’ and ‘Glory to Ukrainian Heroes,’ illustrate their alignment with broader political goals, vividly portraying Clausewitz’s theories in practice. This underscores the pivotal role digital platforms play in shaping the trajectory and perception of modern conflict.

In this evolving landscape of digital warfare, there is a compelling need for a critical reassessment and adaptation of Clausewitz’s theories. Warfare in the contemporary era integrates information, psychology, and technology, demanding a fresh interpretation of traditional concepts like the ‘fog of war.’ The UMOD’s information dissemination and public engagement approach highlights the imperative of incorporating new digital and computational methodologies. When combined with traditional research disciplines, these modern tools become indispensable for achieving a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics of cognitive warfare.

Warfare in the contemporary era integrates information, psychology, and technology, demanding a fresh interpretation of traditional concepts like the ‘fog of war.’

Moreover, the strategic incorporation of emotional and psychological elements, as evidenced in categories like ‘Memes’ and ‘Animals/Children,’ further underscores their significance in analysing and comprehending the intricate nature of contemporary conflicts.

While retaining its foundational relevance, Clausewitzian theory demands a nuanced application in the digital era. Combining traditional military doctrine with modern approaches and perspectives is essential for a comprehensive understanding of contemporary warfare. This integrated approach ensures the continued relevance and effectiveness of strategic analysis, acknowledging the dynamic and evolving nature of the battlefield. By adapting Clausewitz’s insights to the realities of the digital age, strategists and policymakers can adeptly navigate the complexities of modern cognitive conflicts, aligning historical wisdom with current technological advancements.

Dr Amber Brittain-Hale is a co-founder of BrainStates Inc. She is also a professor of leadership at the University of Saint Katherine, and a strategic advisor specialising in geopolitics, digital diplomacy, and leadership. Dr Brittain-Hale earned her PhD in Global Leadership and Change from Pepperdine University. Her research delves into digital diplomacy and infopolitik, the role of gender in diplomacy, narrative analysis related to Russia’s war in Ukraine, and geopolitical strategies addressing Ukraine’s conflict-induced challenges. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone.

[1] Carl von Clausewitz was a distinguished Prussian general and military theorist renowned for his groundbreaking work, ‘On War.’ His proposition—that war essentially operates as an extension of political ambition—has been foundational to generations of military strategy and international relations discourse.

[2] A. Brittain-Hale, “Infopolitik, Digitalization, and Crisis Communication: A Study of State Institutions in Ukraine,” *Graduate Student Research Conference on the Study of Eurasia in the Social Sciences*, 2023b, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Center for Slavic, Eurasian, and East European Studies.; Marleen M. Dekker et al., “Strategy Under Uncertainty: International Conflict and Variation in Information,” 2021.; Mats Eriksson, “Lessons for Crisis Communication on Social Media: A Systematic Review of What Research Tells the Practice,” International Journal of Strategic Communication, vol. 12, 2018, 526-551.

[3] P.F. de Gouveia and H. Plumridge, “Developing EU Public Diplomacy Strategy,” European Infopolitik. http://www.kamudiplomasisi.org/pdf/kitaplar/EUpublicdiplomacystrategy.pdf.

[4] I. Malone and W. Spaniel, “High valuations, uncertainty, and war,” Research & Politics, vol. 8, 2021.

[5] C. Clausewitz, On War, Original work published 1832, 2017, 105.

[6] J. Marson, “The ragtag army that won the battle of Kyiv and saved Ukraine,” Wall Street Journal, https://www.wsj.com/articles/russian-invasion-ukraine-battle-of-kyiv-ragtag-army-11663683336; The quote from Yaroslav Honchar is contained within this article.

[7] C. Clausewitz, On War, Original work published 1832, 2017, 105.

[8] H. Smith, “Clausewitz’s divisions: Analysis by twos and threes,” Infinity Journal, 5(3), 10-13.

[9] Holmes (2017) challenges Clausewitz’s distinction between real and absolute war, suggesting the latter lacks a coherent philosophy, and its contrast with real war is baseless.; Alexander Lukin, “Philosophy of War: Forming a Modern Discourse,” Socium i vlast, 2022.

[10] A. Herberg‐Rothe, Clausewitz’s “Wondrous Trinity” as a Coordinate System of War and Violent Conflict, International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 3, 204-219, https://doi.org/10.4119/UNIBI/IJCV.6.

[11] A. Brittain-Hale, “Slava Ukraini: A Psychobiographical Case Study of Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s Public Diplomacy Discourse,” *Dissertations & Theses @ Pepperdine University – SCELC; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global; Publicly Available Content Database*, Order No. 30487971, 2023-2024, https://www.proquest.com/docview/2845356089.

[12] S. Kaempf, “Lost Through Non-Translation: Bringing Clausewitz’s Writings on New Wars Back In: Small Wars and Insurgencies, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2011.599164.

[13] K. J. Ayhan, “The Boundaries of Public Diplomacy and Non-state Actors: A Taxonomy of Perspectives,” International Studies Perspectives, vol. 20, no. 1, 63–83, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1093/isp/eky010.

[14] Scheipers (2016) delves into the nuanced understanding of Clausewitz’s perceptions of “small wars” and “people’s war,” and highlights the harmonisation of “passion and reason” in war strategies. This article underscores Clausewitz’s conceptualisation of war reaching its ‘absolute perfection’, a regulative ideal, in the realm of smaller, more localised conflicts.

[15] Beatrix Heuser, “Small Wars in the Age of Clausewitz: The Watershed Between Partisan War and People’s War,” Journal of Strategic Studies, 33, 139 – 162, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402391003603623.

[16] C. McIntosh, “Theorising the Temporal Exception: The Importance of the Present for the Study of War,” Journal of Global Security Studies, https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogz040.

[17] Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai, “Inside Ukraine’s Decentralised Cyber Army,” Vice, July 19, 2022, https://www.vice.com/en/article/y3pvmm/inside-ukraines-decentralized-cyber-army.

[18] M. Kaldor, “Inconclusive Wars: Is Clausewitz Still Relevant in these Global Times?,” Global Policy, vol. 1, 271-281, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1758-5899.2010.00041.X; C. Griffin, “From Limited War to Limited Victory: Clausewitz and Allied Strategy in Afghanistan,” Contemporary Security Policy, vol. 35, 446-467, 2014, https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2014.959259

[19] Stephen Kotkin, “The Cold War Never Ended: Ukraine, the China Challenge, and the Revival of the West,” Foreign Affairs, vol. 101, no. 3, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/reviews/review-essay/2022-04-06/cold-war-never-ended-russia-ukraine-war.

[20] Ukraine.ua. (n.d.), Ukraine is a modern country with a thousand-year history 🇺🇦 One of the symbols of our statehood is the link [LinkedIn post], LinkedIn, https://www.linkedin.com/posts/ukraineua_ukraine-is-a-modern-country-with-a-thousand-year-activity-6978294954628427776-INIF.

[21] W. Spaniel and I. İdrisoğlu, “Endogenous military strategy and crisis bargaining,” Conflict Management and the Peace Science, 2023.

[22] S. Pike and D. F. Kinsey, “Diplomatic identity and communication: Using Q methodology to assess subjective perceptions of diplomatic practitioners,” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 1-10, 2021.: O. S. Sobolieva, “Philological science and education: Transformation and development vectors,” https://doi.org/10.30525/978-9934-26-083-4.

[23] K. J. Ayhan, “The Boundaries of Public Diplomacy and Non-state Actors: A Taxonomy of Perspectives,” International Studies Perspectives, vol. 20, no. 1, 63–83, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1093/isp/eky010.

[24] Laura Berry, “100 Speeches in 100 Days of War: Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelensky Rallies His Country,” Los Angeles Times, June 03, 2022, https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2022-06-03/100-speeches-in-100-days-of-war-zelensky-rallies-ukraine.

[25] T. L. Sellnow and M. W. Seeger, “Theorizing Crisis Communication,” 2013; J. M. Scacco, K. Coe, and L. B. Hearit, “Presidential communication in tumultuous times: Insights into key shifts, normative implications, and research opportunities,” Annals of the International Communication Association, vol. 42, no. 1, 21–37, 2018.

[26] A. Brittain-Hale, “Public Diplomacy and Foreign Policy Analysis in the 21st Century: Navigating Uncertainty through Digital Power and Influence,” Graduate Research Conference (GSIS), vol. 4, 2023c, https://doi.org/10.25776/ns11-2e14.

[27] S. Van Sant, “Russian propaganda is targeting aid workers,” Foreign Policy, August 01, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/08/01/russia-disinformation-ukraine-syria/.

[28] Anastasiia Romandash, “Ukraine’s IT Army: Digital Resistance to Russian Propaganda,” Civil Resistance, Digital Peacebuilding, Ukraine War, 2022.

[29] Z. A. Huang, “A historical–discursive analytical method for studying the formulation of public diplomacy institutions,” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, vol. 18, 204-215, 2021.

[30] O. A. Garard, ed., An Annotated Guide to Tactics: Carl von Clausewitz’s Theory of Combat, 1st ed. (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps University Press, 2021), ISBN: 978-1-7320031-3-2, LCCN 2021011565.

[31] NATO Review, “Countering Cognitive Warfare: Awareness and Resilience,” May 20, 2021, https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles.html.

[32] M. Kissel and Nam-Choon Kim, “The emergence of human warfare: Current perspectives,” American journal of physical anthropology, 168 Suppl 67 (2019): 141-163, https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.23751.

[33] E. Schwartz and H. Litwin, “Warfare exposure in later life and cognitive function: The moderating role of social connectedness,” Psychiatry Research, 278 (2019): 258-262, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.06.026.

[34] Antulio J. Echevarria II, “Putin’s Invasion of Ukraine in 2022: Implications for Strategic Studies,” The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters, vol. 52, no. 2, 2022, https://doi.org/10.55540/0031-1723.3150.

[35] N. J. Cull, From soft power to reputational security: rethinking public diplomacy and cultural diplomacy for a dangerous age. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 18, 18-21, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-021-00236-0.

[36] H. Smith, “Clausewitz’s divisions: Analysis by twos and threes,” Infinity Journal, 5(3), 10-13.

[37] M. H. Van Herpen, “Putin’s Propaganda Machine: Soft Power and Russian Foreign Policy,” Rowman & Littlefield; M. H. Van Herpen, “Putin’s wars: The rise of Russia’s new imperialism,” Rowman & Littlefield.

[38] O. A. Garard, ed., An Annotated Guide to Tactics: Carl von Clausewitz’s Theory of Combat, 1st ed. (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps University Press, 2021), ISBN: 978-1-7320031-3-2, LCCN 2021011565.

[39] H. D. Lasswell, Power and Personality, Taylor & Francis Group, ISBN 1138530573, 9781138530577.

[40] H. D. Lasswell, “The structure and function of communication in society,” in L. Bryson, Ed., The communication of ideas, The Institute for Religious and Social Studies, 1948b.; 10. Доктрина інформаційної безпеки України (2017). Translated from Ukrainian: DECREE OF THE PRESIDENT OF UKRAINE NO. 47/2017. On the Decision of the National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine of December 29, 2016, “On the Doctrine of Information Security of Ukraine,” http://www.president.gov.ua/documents/472017-21374.

[41] D. Zimand-Sheiner, S. Levy, and E. Eckhaus, “Exploring Negative Spillover Effects on Stakeholders: A Case Study on Social Media Talk about Crisis in the Food Industry Using Data Mining,” Sustainability, 2021.

[42] P. Singer and E. T. Brooking, “LikeWar: The weaponisation of social media,” HarperCollins, 2018.

[43] Brittain-Hale’s (2023a) research provides an incisive examination of digital diplomacy within cognitive warfare, asserting its centrality in state strategy. The study reveals how states navigate the digital terrain using tactics aimed at influencing international discourse, framing narratives, and manipulating information to achieve geopolitical objectives.

[44] W. Spaniel and B. Savun, “Less Is More? Shifting Power and Third-Party Military Assistance,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2023.

[45] P.F. de Gouveia and H. Plumridge, “Developing EU Public Diplomacy Strategy,” European Infopolitik. http://www.kamudiplomasisi.org/pdf/kitaplar/EUpublicdiplomacystrategy.pdf.

[46] L. Roselle, A. Miskimmon, and B. O’Loughlin, “Strategic narrative: A new means to understand soft power,” Media, War & Conflict, vol. 7, no. 1, 70–84, 2014; F. Santini, “Defending Ukraine’s Information Space,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2022.

[47] K. J. Ayhan, Ed., Korea’s Public Diplomacy, Hangang Network & MOFA, 2016, ISBN 979-11-959976-0-2.

[48] A. Shekhovtsov, “Bringing the Rebels: European Far Right Soldiers of Russian Propaganda,” Briefing, Sep. 2015.

[49] H. D. Lasswell, Propaganda technique in the world war, MIT Press, 1938.

[50] A. F. Cooper, “Adapting Public Diplomacy to the Populist Challenge,” Debating Public Diplomacy, 2019; Y. Osipova-Stocker, E. Shiu, T. Layou, and S. Powers, “Assessing impact in global media: methods, innovations, and challenges,” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, vol. 18, 287-304, 2021.

[51] T. Just, “Public diplomacy and domestic engagement: The Jewish revival in Poland,” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, vol. 11, 263-275, 2015.

[52] Ulrike Kleemeier, “Moral Forces in War,” in Clausewitz in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Hew Strachan and Andreas Herberg-Rothe, Oxford Academic, 2007, https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199232024.003.0007.

[53] E. A. Cohen, “Cometh the hour, cometh the man,” The Atlantic, March 01, 2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/03/putin-ukraine-invasion-military-strategy/622956/.