Abstract: This paper critically examines the Western military’s reliance on manoeuvrist warfare as defined by NATO, positing that this approach may prove myopic in the context of potentially unlimited warfare. It argues that expecting a single set of forces to achieve decisive results against a resilient adversary swiftly is a high-risk strategy. Furthermore, an excessive focus on the manoeuvrist approach may disconnect military efforts from their fundamental political objectives, leading to tactical and operational disorientation and forfeiture of the strategic initiative. In response, the paper advocates for a recalibration of strategy towards attriting the adversarial Centre of Gravity instead of expecting definitive successes from quick and clean land operations. This approach requires Western forces to accept the dire consequences of strategic attrition and embrace prolonged and symmetric warfare strategies to secure favourable outcomes.

Problem statement: Will Western military doctrine adapt to the challenges of strategic attrition in preparation for a potential armed conflict with peer competitors?

So what?: Adhering rigidly to the manoeuvrist approach leaves Western militaries ill-prepared for the evolving realities of modern conflict, as seen in Ukraine. Adaptive strategies, rooted in strategic patience, measured realism, and the wisdom of classic military theory, are essential for successful outcomes.

Source: shutterstock.com/PeopleImages.com – Yuri A

950 Days War in Ukraine

Over 950 days of large-scale war in Ukraine have forced Western military analysts to reassess long-held beliefs. Decades of military theory, finely tuned during relative peace in Europe, have been savagely upended by the fallout of an ever-intensifying conflict. Valery Zaluzhnyi, former Commander-in-Chief of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, noted this growing intensity when he recently described the war in Ukraine as a “total” war for his country.[1] In a speech bristling with pathos, he compared the military theory behind Ukraine’s struggle to the people’s wars of the Napoleonic ages, which inspired Carl von Clausewitz to write On War.[2] Although this assessment may not align with measured scientific analysis, it captures the overall sense of urgency the Ukrainian defenders are conveying to their Western supporters through every available channel. Zaluzhnyi, now the Ukrainian ambassador to the UK, appealed to Western societies to muster their defensive capabilities and “temporarily give up a range of freedoms for the sake of survival” should the need arise.[3] “Among such resources are the economics, finance, population, and allies. [..] Thus, the readiness for war will be determined not only by the readiness of the army to repel aggression but also by the readiness of society to confront the enemy,” Zaluzhnyi added, summing up the strategic essence of a nation’s will to fight for its freedom.[4]

Valery Zaluzhnyi, former Commander-in-Chief of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, noted this growing intensity when he recently described the war in Ukraine as a “total” war for his country.

Meanwhile, Ukraine’s Western supporters have avoided key pillars of irreversible commitment, such as Ukrainian NATO membership or the deployment of their military forces, opting instead for a strategy grounded in political signalling, reliance on technologically advanced “wonder weapons,” and carefully measured sustainment efforts for fear of uncontrolled escalation.[5] Conversely, a renewed and repeatedly demonstrated “cult of the offensive” risks conflating attrited Ukrainian warfighting capabilities with courage and heroism, potentially hastening operational failure, as seen in the failed counteroffensive in 2023.[6]

![Destroyed Western military equipment during the failed Ukrainian offensive in 2023[7]](https://tdhj.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Schaebler_01.jpg)

Destroyed Western military equipment during the failed Ukrainian offensive in 2023[7]

In short, Russia and Ukraine have demonstrated that resilience and sacrifice often outweigh military technology and tactical ingenuity in ensuring survival and endurance in a war of attrition. As the evolving nature of the war in Ukraine continues to drive rapid tactical and operational adaptations, NATO members must critically reassess their current doctrinal foundations and strategic assumptions regarding the manoeuvrist approach.[12]

The Western Manoeuvrist Approach

The latest iteration of NATO AJP 3.2, released on the eve of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, defines the manoeuvrist approach as “synonymous with the term manoeuvre warfare.”[13] At the core of this doctrine lies the expectation that manoeuvre serves as the fundamental solution in Western tactical and operational warfare. Although conventional Large Scale Combat Operations (LSCO) between NATO and its European neighbours have yet to materialise, the mere prospect has shaped military planning since the beginning of the Cold War. NATO AJP 3.2 emphasises “bold and decisive action,” aimed at “seizing and holding the initiative, and attacking the enemy’s understanding, will, and cohesion.”[14] The doctrine states further that “in combat, the manoeuvrist approach invariably includes elements of movement, fires and defence,” but any defensive measure should only serve as necessary “means to the end, which is the enemy’s defeat.”[15] Defeat is achieved through a “high tempo of operations to continuously force an opponent to react” and to render adversaries “incapable of resisting effectively by shattering their cohesion rather than destroying each of their components through incremental attrition.”[16] In line with these principles, NATO’s 2022 “new force model” called for increased readiness and reduced national mobilisation periods.[17] It focused on mobility, agility, and early exploitation of enemy vulnerabilities to enforce rapid decisions without risking an attritive culmination and loss of initiative.

NATO AJP 3.2 emphasises “bold and decisive action,” aimed at “seizing and holding the initiative, and attacking the enemy’s understanding, will, and cohesion.”

The goal is to shorten the duration of military campaigns and optimise military engagement to the necessary minimum. These aims are as ambitious as they are risk-oriented. However, they did not evolve without legitimacy. For military powers in central Europe, shortening military campaigns while adhering to the dictates of geography and politics has always been fundamental to military planning, as have the traumatic experiences of two World Wars.[18] Today, Western doctrine refers to manoeuvre within the greater context of “Multi-Domain-Operations (MDO)” when employing AJP-3.2. However, since Europe’s compass of collective defence points starkly eastwards, its war-critical impact is under scrutiny.

You and Whose Army?

NATO faces the dual challenge of maintaining credible, affordable and sufficient forces to deter adversaries in peacetime and ensuring high standards of interoperability, cohesion, and command and control (C2) to enable the manoeuvrist approach to be effective in LSCO.[19] The latest NATO summits have focused on pledging cohesion in support of common causes and values, introducing new members and strategic cornerstones, and easing NATO off the path to what French President Emanuel Macron called “brain death” in 2019.[20] The new strategic focus is “Deterrence and Defence,” allowing NATO to commit to LSCO as the prioritised conflict scenario.[21] Consequently, large-scale NATO exercises, such as “Steadfast Defender 2024,” are designed to prepare coalition forces for rapid deployment and demonstrate political and military cohesion, echoing the purpose of Cold War REFORGER (REturn of FORces to GERmany) exercises.[22]

In contrast to ambitions and expectations, a steady stream of studies and articles on Western military readiness paints a bleak picture of the economic and logistical capacity required to sustain protracted future LSCO against peer adversaries.[23] For instance, the inherent challenges to NATO’s cohesion—brought about by its growing number of members, diverse values, and varying interests—highlight a widening gap between military realities and political expectations, as Jeroen Verhaeghe astutely observed in 2021.[24] Further, the post-Cold War downsizing of military forces, often termed the “peace dividend,” aimed at cutting costs and redirecting resources to peacetime economies.[25] This shift was underpinned by a strong belief in a perpetually peaceful and liberal Europe that needed to deflect the fallout of global conflicts, overpopulation, and dwindling resources by militarily enforcing a rules-based order.[26]

The inherent challenges to NATO’s cohesion highlight a widening gap between military realities and political expectations, as Jeroen Verhaeghe astutely observed in 2021.

In response, the original role of military forces in state-on-state conflict gave way to various contemporary interpretations of military utility in global foreign policy, aiming at nudging dissenting states towards a shared future. Along the way, the Western understanding of war promoted wishful thinking and overconfidence in contemporary and short-lived military problem-solving capabilities. The Vietnam War, Operation Desert Storm in 1991, and NATO interventions in the Balkans represented the milestones towards the pinnacle of hegemonic overreach: The Global War in Terror (GWOT). However, this shift led to a reciprocal decline in the holistic understanding of conflict with peer competitors and a partial loss of focus, defence priorities and coherent strategy. The Former U.S. presidential advisor and retired General H.R. McMaster called the resulting “strategic narcissism” an assumption “that military competition was finished and that future wars would be easy.”[27]

Further, the peace dividend also took its toll on force generation as all-volunteer forces replaced mass-conscripted armies.[28] As a result of military capabilities struggling to keep pace with political aspirations, an ever-expanding army of ageing staff officers flooded conference halls and administrative bureaucracies. At the same time, the ranks of enlisted soldiers dwindled.[29] To maintain appearances, meticulously choreographed military exercises—designed for success—replaced challenging snap drills meant to test limits at the LSCO level. Central to these presentations was the dogmatic application of manoeuvre warfare as a universal solution.[30]

NATO and EU military planners in Europe have tried to balance their assets around a “single set of forces” capable of national and collective defence while also serving as an asset for global foreign policy.[31] This concept relies on pooling military and industrial resources within alliances, often leaning heavily on “burden sharing” and minimising excess capacities, thereby quietly burying European aspirations of strategic autonomy by means of establishing collective military enablers outside of NATO.[32] To manage such complex peacetime forces and stockpiles, NATO members have adopted principles of business economics, including globalised supply chains, lean production, and strict oversight bureaucracies.[33] Also, most NATO members have neglected compliance with spending and force structure guidelines for decades.[34]

While more cost-efficient, this approach has reduced surge capacities in times of crisis. Through decades of expeditionary engagement, European militaries have created a deterrent façade at the cost of war-faring competence. Exemplarily regarding the British Armed Forces, a pillar of NATO resilience in Europe, British analyst Matthew Savill commented recently that this has led to hollowed-out forces unfit to fight prolonged wars.[35] This precarious and “threadbare” state of readiness has become common knowledge, regularly declared within the responsible political circles and published in mainstream media.[36] The German historian Soehnke Neitzel, in 2024, commented that the Bundeswehr currently would only be able to “die with honour” in the case of an LSCO.[37] While undermining credible deterrent effects, the issue runs deeper. Persisting national caveats on matters of logistics, culture, interoperability, communication, and digital friction have bloated the elephant sitting in every international NATO planning conference: The combat value of this multinational force should exceed the sum of its parts for the alliance to benefit its members. Jeroen Verhaeghe poignantly remarked in 2021 on this subject that “[cultural and historical] diversity is a given and, if there is any truth to Peter Drucker’s quote that culture eats strategy for breakfast, I am sure that it would treat NATO doctrine as a late evening snack.”[38]

In essence, Western alliance cohesion is under increasing duress. Its defence-industrial base needs urgent reform, with even the combined economic power of the U.S. and EU struggling to meet the expectations of institutionalised support of the Ukrainian war efforts since 2014.[39] Indicators such as shell production rates and military recruitment numbers suggest that NATO economies are currently underprepared for LSCOs, which require endurance in prolonged attrition rather than a reliance on offensive resolve.[40] A spontaneous renaissance of Western military might in light of future threats has not proven feasible.

Western alliance cohesion is under increasing duress. Its defence-industrial base needs urgent reform.

In 2024, the “Commission on the National Defense Strategy” of the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) found that “US industrial production is grossly inadequate to provide the equipment, technology, and munitions needed today, let alone given the demands of great power conflict,” while the U.S. also faces “the most challenging global environment with the most severe ramifications since the end of the Cold War.”[41] Assuming this report is representative of the condition of Western forces in general, there is little room for contingency planning, a successive manoeuvrist operation, significant reserves, or resources to draw upon if the initial assault fails to achieve its decisive aims.

On the other hand, think tanks have independently assessed that Russian leadership and its allies have understood the need to adapt to battlefield realities; Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, writing in Foreign Affairs, acknowledged that it “is the regime’s resilience and its demonstrated capacity to adjust” that allows Russia to grind on into the Donbas, despite all resistance.[42] The Russian armed forces are overcoming setbacks and focusing on strategic resilience and a long war in Ukraine, seemingly undeterred by staggering losses in personnel and materiel.[43] Simultaneously, Russia is deepening its ties with other actors in its vicinity, solidifying the strategic framework for future military alliances aimed at the Western hemisphere.[44]

To illustrate the situation, one might imagine a highly skilled martial artist, technically adept but lacking endurance, struggling through a 12-round slug-fest against a relentless heavyweight opponent. Although this analogy simplifies the complexity, it effectively highlights the core challenge.

![Classic theories on warfare often compare war to the struggle of two individuals for dominance; Source: Author.[45]](https://tdhj.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Schaebler_02-1024x585.jpg)

Classic theories on warfare often compare war to the struggle of two individuals for dominance; Source: Author.[45]

Winning the Battle but Losing the War

The strategist Christopher Tuck has cautioned against a Western overreliance on the manoeuvrist approach, arguing that “manoeuvre warfare does not actually exist as a discrete style of warfare. Instead, it is an imaginary construct, fabricated and instrumentalised by Western militaries to serve various political and value-related functions.”[46] Tuck’s evaluation may seem severe, but it highlights the necessity for Western military planners to account for potential failures in manoeuvre operations and prepare for alternative contingencies. With a high probability, adversaries will counter NATO’s focus on mobility and initiative by denying or disabling these key factors through Anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) strategies, incentivising positional warfare and attrition.[47] Amos C. Fox further critiqued the manoeuvrist approach as a “solution looking for a problem,” noting that it fails to address “warfare’s conditional character.”[48] Instead, it overly emphasises initiative, tempo, and indirect, decisive strikes against enemy cohesion as the ultimate approach. Even for the U.S. Marine Corps, a force inherently prone to methods of manoeuvre, Christopher A. Denzel appealed that opening the “doctrinal straitjacket” would allow to “talk more maturely” about attritional or positional methods of warfare and “strip MW [manouevre warfare] down to a meaningful and employable definition.”[49]

Contrary to common misconceptions, attritional warfare is not synonymous with stalemate. It is primarily concerned with wearing down the enemy to the point of collapse. The predictability of results outweighs the focus on efficacy. From this perspective, military “victory is assured by careful planning, industrial base development and development of mobilisation infrastructure in times of peace, and even more careful management of resources in wartime,” Alex Vershinin stated when commenting on the revelations of the Russo-Ukrainian war.[50] However, currently, no validated doctrinal alternative to manoeuvre warfare has been established in the West. This leaves NATO’s power-projection capabilities underprepared to either use operational alternatives to the manoeuvrist approach or effectively counter an adversary that has adopted such methods.

Contrary to common misconceptions, attritional warfare is not synonymous with stalemate.

The Prussian general Carl Von Clausewitz emphasises that the specific aim of an operation must align with the broader purpose of war, achieved through appropriate means and methods.[51] The conditions dictate the mode of operations, not vice versa. The battlefield cannot repeatably be shaped for renewed manoeuvrist warfare once a force has firmly lost the initiative to pursue the Schwerpunkt.

Who or What is a Schwerpunkt?

In On War, Clausewitz frequently uses the loosely defined term Schwerpunkt or “main effort” to describe a decisive focus point in military action.[52] The concept of Schwerpunkt has long been central to Prussian and German military doctrine, where the focus was on concentrating force against the enemy’s critical mass.[53] As a tactical or operational military aim, it leads to the means of employing maximum leverage and tempo to break the adversarial will to continue the war. The manoeuvrist approach offers an optimised solution to achieve these aims since it tries to attack the core of an enemy’s potential and not waste excess energy on secondary aims.

While military theory aligns, the realities of warfare necessitate a broader understanding and acceptance of alternative methods as integral to achieving overall military objectives. To complicate matters, there has been significant confusion between the terms Schwerpunkt and the Centre of Gravity (CoG), both of which military strategists have reinterpreted and redefined over time.[54] Initially, the term CoG was a byproduct of early translations of “On War,” meaning roughly the same as Schwerpunkt but in a less specific context. This confusion has offered space for thought and interpretation, gradually separating the CoG from its etymological ancestry.[55] While widely accepted as necessary for strategic guidance, the theory proved elusive when it came to actually targeting the CoG in a state-on-state war, leading the term to pollute relevant doctrine.[56] In 2014, John Butler offered a creative approach for military planners challenged with identifying a CoG, which he named “Godzilla Methodology.”[57] Here, the legendary sea monster comes to the rescue of Japanese Forces at the end of the Second World War. It successfully neutralises the U.S.’ warfighting capabilities one by one until defeat. The loss of this final and decisive capability has to indicate the CoG in Butler’s methodology.[58]

![Godzilla in search of the Centre of Gravity; Source: Author.[59]](https://tdhj.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Schaebler_03-1024x725.jpg)

Godzilla in search of the Centre of Gravity; Source: Author.[59]

Clausewitz recognised this, noting that wars are often decided by the “unacceptable [material and moral] cost” rather than pure military outcomes. After all, war being a political tool meant that the effects of warfare also influenced the decision-makers far behind the frontlines. Antulio J. Echevarria explained in 2003 that “Clausewitz did not distinguish between tactical, operational, or strategic centres of gravity; he defined the centre of gravity holistically—that is, by the entire system (or structure) of the enemy—not in terms of level of war.”[60] He further added the critical distinction that a CoG and its all-decisive effect can only be sought for in unlimited wars, or with Clausewitz’s words, “absolute wars.”[61] These wars of “annihilation,” as Christopher Bassford specified in 2023, are the opposite of elective campaigns with limited aims, the West has become accustomed to since the 1950s.[62]

Clausewitz did not distinguish between tactical, operational, or strategic centres of gravity; he defined the centre of gravity holistically, not in terms of levels of war.

In a comparative study in 2024, Mauro Mantovani and Michel Wyss summarise Clausewitz’s main argument as aiming to “defeat the adversary as quickly as possible by directing the main blow against whichever target will shatter his cohesion decisively.”[63] To help identify commonalities between different theories of CoG, the authors utilise a teleological perspective, concluding that CoG is a more abstract, metaphysical and strategic phenomenon.[64] This aligns with the original idea that wars can be decided by correctly identifying and striking the adversarial Schwerpunkt but offers a broader perspective, acknowledging that a force field of critical values exists above the operational theatre.

Historically, US military doctrine evolved the concept throughout the 1980s in the U.S. Army Field Manual 100-5, which expanded CoG to include elements like “the mass of the enemy army, the enemy’s battle command structure, public opinion, national will, and an alliance or coalition structure.”[65] Within this interpretation of the CoG, the greater concept of AirLand battle was enclosed, a doctrine that focused on deep strikes against an enemy CoG, strictly combined with the manoeuvrist approach.[66] Initially, this strategy appeared poised for military success, particularly against an internationally isolated and technologically inferior adversary with a diminished will to fight.[67]

However, after the understanding of the CoG in American doctrine again was mangled to uneasily fill the strategic void of fighting small wars in the GWOT, it must now be deconstructed back to its roots in potential European state-on-state conflict. For this, it is rewarding to revisit literature from the 1980s. Shortly before the end of the Cold War, the military scholars Metz and Downey identified five critical factors of a dynamic CoG at the political and strategic level: industrial areas, public morale, alliance cohesion, capital cities, and the willpower of political elites.[68] This basis for future strategic theory can be excavated and adapted to current requirements.

Adding the Missing CoG to the Machine

The Cold War approaches to CoG theory allow planners to critically reevaluate the manoeuvrist approach’s effectiveness in LSCO, particularly in a scenario where nuclear deterrence limits the use of conventional forces. A resulting and otherwise unlimited LSCO would prove highly attritious to all sides. This point is critical when democracies go to war within alliances, such as NATO. As history shows, conflict and threat perception profoundly influence national voter behaviour. Such periods reveal significant shifts between support and opposition within similar groups, shaping volatile war and peace orientation patterns.[69]

The Cold War approaches to CoG theory allow planners to critically reevaluate the manoeuvrist approach’s effectiveness in LSCO, particularly in a scenario where nuclear deterrence limits the use of conventional forces.

The attritional effect on a strategic CoG, where factors like public morale and alliance cohesion play crucial roles, can lead to a war’s conclusion even without decisive military action. Even in primarily national military endeavours, strategic attrition can result in premature strategic ends. The experiences of the U.S. in Vietnam exemplified the gradual erosion of a CoG in a limited conflict scenario. Political decision-making heavily correlated with domestic needs and sometimes overruled the battlefield’s military requirements during elections.[70] Additionally, Andrew Mack revealed a paradox in asymmetrical environments: numerical superiority often translates into strategic and operational disadvantages on the battlefield.[71] The disastrous consequences of underestimating the true nature of war while incorrectly assessing the opposing and its own CoG finally became evident to the American public during the Tet Offensive in 1968.[72] Under the relentless pressure of a perpetual conflict, public support eroded, and alliance cohesion crumbled. Henry Kissinger, in 1969, agreed when commenting on the U.S. intervention in Vietnam: “We fought a military war; our opponents fought a political one. We sought physical attrition; our opponents aimed for our psychological exhaustion. In the process, we lost sight of one of the cardinal maxims of guerrilla war: the guerrilla wins if he does not lose. The conventional army loses if it does not win. The North Vietnamese used their main forces the way a bullfighter uses his cape—to keep us lunging in areas of marginal political importance.”[73] The resulting disorientation of misaligned political, military and strategic goals led to reciprocal exhaustion on the different levels of this, ultimately, aimless war.

Clausewitz expressly warned against wars based on weak resolve and limited motives. As he termed them, fighting disoriented cabinet wars for indistinct reasons would fail: “The political object is the goal, war is the means of reaching it, and means can never be considered in isolation from their purpose.”[74] The quote underscores the importance of clear aims, foresight, patience, and resource management in warfare, where the attritional impact on the CoG will ultimately determine the outcome of a conflict. In Clausewitz’s words, “Wearing down the enemy in a conflict means using the duration of the war to bring about a gradual exhaustion of his physical and moral resistance.”[75] In a future LSCO scenario, the warring parties will compete for dominance on the battlefield and resilience within their CoGs to achieve lasting stability. While battlefield success should theoretically be ensured by overwhelming force from large military alliances like NATO, these very coalitions create vulnerabilities that can be exploited through attrition of their cohesion and an erosion of their morale. Although a national people’s war for survival may prove that individual societies are more resilient, today’s geopolitical powers are deeply intertwined in multiple and heterogenic alliances. This has been evident in multinational operations from Afghanistan to Syria, making alliance cohesion a critical vulnerability in future LSCOs. For adversaries, exploiting these weaknesses through global hybrid warfare and prolonged military and financial strain—such as in the grinding battles of Ukraine—presents a promising strategy for the eventual dominance of will despite numerical disadvantages.[76]

“As Long as it Takes”

From an unpolitical and strictly strategic perspective, the war in Ukraine should be understood as a limited, conventional LSCO between two sovereign nations—one of which has regional military aims. So far, Russia officially views its “special military operation” as a modern cabinet war, marking its political ambition as limited in scale.[77] However, its simultaneous insistence on escalation dominance theory indicates that it does not have to stay that way.[78] At the same time, Ukraine understands the war as a people’s war of national survival. It also aligns with Western values, stressing a broader cause of defending national sovereignty and international law concepts. Consequently, Ukraine is so far neglecting any opportunity for compromise.[79]

From an unpolitical and strictly strategic perspective, the war in Ukraine should be understood as a limited, conventional LSCO between two sovereign nations—one of which has regional military aims.

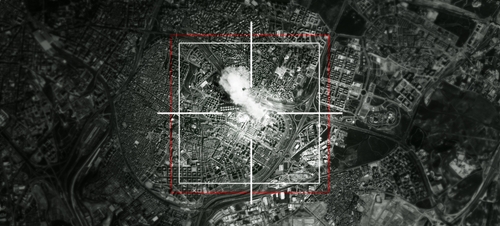

At a level high above the battlefields of Ukraine, a potentially unlimited geopolitical conflict is being fought by proxy, encompassing informational and cyber warfare, nuclear threats, international sanctions and private economic interests.[80] The conflict’s decades-old genesis primarily lies within the consequences of the Soviet implosion and the resulting unipolar moment, the released tensions of which are increasingly exacerbated by hybrid operations on either side today.[81] The conclusion of Russia’s war in Ukraine will define the leading hegemon in Eastern Europe.

In 2022, the U.S. Secretary of Defense, Lloyd J. Austin III, summarised the roots of Western coalition strategy: “We want to see Russia weakened to the degree that it can’t do the kinds of things that it has done in invading Ukraine.”[82] For a Western ad-hoc coalition to successfully gather behind a strategic aim of this magnitude, significant military and industrial efforts, hybrid means, and the resilience to share the burden and accept the consequences collectively are vital. Given that Russia is an aspiring military hegemon with the inherent self-esteem of a superpower, the Western mantra of “as long as it takes” offers a general insight into the coalition’s commitment to the cause.[83]

In other words, the Western CoG, led by the U.S. and including NATO, the EU and over 50 state actors, is deeply engaged in an attritional hybrid struggle with its adversary.[84] From this perspective, the CoG has expanded from Kyiv to Washington, integrating much of political and military Europe. Consisting of dozens of democracies, alliance cohesion and public support are paramount to stabilising the Western CoG. However, as exemplified by the Hungarian dissent of coalition principles over sanctions and unilateral negotiations with Russia in 2024 or the growing impact of the war on Western elections and economies, the attritional strain on Western partnerships is increasingly palpable.[85] Still, Western military force generation and revitalisation continue to be constricted by an inhibited industrial base, the regular allocation of materiel and financial resources towards Ukraine with no return and the lack of a conclusive and active European-led strategy beyond generally deterring Russia at NATO borders.

Further, Ukraine’s capacity to continue the war significantly depends on the cohesion of the Western coalition, as its CoG has all but merged with its Western supporters. Its state finances are in disarray, and the coalition can only avoid a Ukrainian default by regularly sending more aid and increasing the national debt.[86] This connection is then also reciprocal. Western actors are tied to military and political outcomes in Ukraine, as the conflict impacts their industrial capacity, political trajectories, alliance cohesion, international credibility, public morale, and the future of the Western world order.[87]

The Russian CoG, though less clearly identifiable, also extends beyond Russia and its immediate allies and envelops a growing number of associates, such as China, parts of Africa, Iran and North Korea.[88] Assessing its resourcefulness and resilience is clouded by informational warfare.[89] The overwhelming influx of information in the public domain has had a dichotomous effect, both stifling and liberating the dissemination of war-related data, thereby disrupting the foundation for coherent analysis and planning. It is the new “fog of war.”[90] However, it seems that the direct involvement of Russian forces, a centrally controlled political and industrial base, and a focus on national interests unconstrained by Western interpretations of morality and lawfare have enabled this anti-Western CoG to prioritise its objectives and follow its interests more efficiently.[91] Additionally, any attritional approach to war will likely be less constrained by public opinion, which allows for greater resilience and state stability when facing stagnant phases or operational defeats. While recent reports of North Korea contributing substantial numbers of personnel to the Russian Armed Forces still have to be clarified, the war-prolonging effects of vast amounts of materiel provided by Russia’s closest partners is well-established.[92]

The Russian CoG, though less clearly identifiable, also extends beyond Russia and its immediate allies and envelops a growing number of associates, such as China, parts of Africa, Iran and North Korea.

Essentially, both sides are “boiling the frog,” meaning the slow but steady grinding of capacities and capabilities to continue the conflict of interests in a quasi-limited fashion.[93] Technological or doctrinal changes have yet to reconstitute any operational endeavour as war-decisive. The resulting battlefield paralysis has uprooted cornerstones of contemporary military theory, such as force-ratio analysis, the importance of initiative, an agile and effective C2, and the significant concentration of force.[94] The Schwerpunkt of old has diluted into clouds of enablers and disablers, relying on decentralised and non-standardised improvisation on a company level. Successfully executed territorial gains mainly lie within this context, reviving the 1918 dogma of “bite and hold,” as Robert Rose pointed out.[95]

Such activities necessitate a shift of perspective to the strategic level and involve re-reading military scholars such as Boyd or Warden for insights on secondary and tertiary strategic effects in war and how to exploit static phases in warfare.[96] Further, the Clausewitzian concept of friction transpires into the digital realm, including an increasing dependence on electrical power, mobile communications and electronic warfare. The consequence is a phenomenon that can be coined as digital friction, transforming the Prussian phrase: “Everything is very simple in war, but the simplest thing is difficult,” into the realm of informational and digital conflict.[97] For instance, the significant strategic effects of Starlink satellite support for Ukraine marked digital friction’s undeniable relevance for future warfare.[98]

While, at the time of writing, the operational art of manoeuvre has lost its former allure in Ukraine, it can still add value to the struggle if technological and tactical conditions allow it. It can highlight vulnerabilities in the adversarial posture, serve propagandistic and informational purposes, and boost CoG morale.[99] Ukraine has used these effects successfully in the past, producing high-profile operations that have proven beneficial to the Western CoG’s cohesion, as witnessed in the temporary bridgehead at Krynky or the recent incursion towards the Russian city of Kursk.[100] However, after such operations eventually culminated, the inverse consequences also transpired strategically, making the overall cost-benefit assessment challenging. Further, the regularly rising expectations towards missile-enabled deep strikes and advanced targeting of critical enablers on either side, such as advanced energy infrastructure, bridges or resource supply chains, may also be misleading in their war-decisive effects. Rather than expecting wonders, such means must be understood within a theoretical framework of grand strategy that is not limited to territory, propagandistic signalling or believing in simplified ends to the complex political conflict.[101] Paraphrasing former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark A. Milley in 2023, one of the primary lessons is to mentally and emotionally abstain from “silver bullets” in war.[102]

Paraphrasing former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark A. Milley in 2023, one of the primary lessons is to mentally and emotionally abstain from “silver bullets” in war.

So far, neither side has been able to untangle the operational deadlock that has likely cost hundreds of thousands of lives in the region. A 1000-mile Gordian knot of trenches paralyses initiative, representing exactly what the manoeuvrist approach meant to overcome.[103] Meanwhile, the relentless use of shells, glide bombs, mines, and drones suggests that a rigid commitment to fire and manoeuvre tactics will continue to result in costly sacrifices on all sides and that new approaches to war as a means of conflict resolution are necessary.[104]

Indirect Attrition

The necessity for essential items such as entrenching tools becomes immediately apparent when observing recent footage from the war in the Donbas. Incidentally, this observation inspired the creation of this essay and contrasts with the author’s experience: in 2013, he was ordered to return his military-issued shovel as there was no apparent need for it during the GWOT era.

While kinetic destruction devastates Ukraine, the war’s political outcome will be strongly influenced by strategic attrition. The conflict has exposed the diminished effectiveness of manoeuvre warfare in resolving limited political state-on-state conflicts with military means. For Western military planners, this indicates admitting more visceral alternatives to the manoeuvrist approach for doctrinal validation. Military analysts should guide political leaders through the complex realities of armed conflict, where attritional and positional warfare take precedence. Military strategies must become more holistic and realistic, focused on achieving durable peace instead of following outdated concepts of victory and defeat. A strategic and political rediscovery of Clausewitz’s theory of war as a political process needs to be accepted and then augmented by what this war teaches to the open-minded. In response, Western forces must humbly adapt to the logistical challenges and the horrifying devastation future prolonged conflict promises. Prioritising basic training over specialisation while focusing on building extensive national personnel reserves and stockpiling materiel will streamline military solutions, better prepare Western forces for the full spectrum of future warfare, and help restore credible military deterrence in Europe. Ready your shovels and embrace the grind!

Alexander Schäbler is a Captain (OF-2) in the German Armed Forces, currently serving as a Youth Information Officer. He is responsible for educating the German public on defence and security matters. His military career includes various positions in the military medical branch of the German Armed Forces and deployments to Afghanistan and Mali. He holds an MA in Strategic Studies. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of the German Armed Forces.

[1] Elena Onischenko, “Free World Needs to Wake Up and Think About How to Protect Its Citizens and Countries,” Rubryka, July 23, 2024, https://rubryka.com/en/2024/07/23/vilnyj-svit-maye-prokynutysya-j-zadumatys-yak-zahystyty-svoyih-gromadyan-i-krayiny-zaluzhnyj-vystupyv-u-londoni/.

[2] Idem.

[3] Idem.

[4] Idem.

[5] Adam Entous and Julian E. Barnes, “U.S. Intelligence Stresses Risks in Allowing Long-Range Strikes by Ukraine,” New York Times, September 26, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/26/us/politics/us-ukraine-strikes.html.

[6] Doug Bandow, “Ukraine’s Vain Search for Wonder Weapons,” Cato Institute, August 24, 2023, https://www.cato.org/commentary/ukraines-vain-search-wonder-weapons.

[7] “Destroyed Tanks and Armored Vehicles in Ukraine,” photograph by the Russian Ministry of Defense Press Service, ZDF, accessed August 2024, https://www.zdf.de/nachrichten/politik/panzer-leopard-erbeutet-ukraine-krieg-russland-100.html.

[8] Nigel Walker, “Conflict in Ukraine: A timeline (current conflict, 2022 – present),” House of Commons Library, August 2024, https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9847/.

[9] Julian G. Waller, “Why Putin Is More Resilient Than You Think,” Foreign Affairs, August 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/russia/putin-resilient.

[10] David Saw, “The Rise and Fall of the Russian Battalion Tactical Group Concept,” Euro-SD, November 2022, https://euro-sd.com/2022/11/articles/exclusive/26319/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-russian-battalion-tactical-group-concept/.

[11] Grace Mappes et al., “Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment, June 02, 2024,” Institute for the Study of War, accessed August 2024, https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-june-2-2024.

[12] Can Kasapoglu, “NATO Is Not Ready for War: Assessing the Military Balance between the Alliance and Russia,” Hudson Institute, June 2024, https://www.hudson.org/security-alliances/nato-not-ready-war-assessing-military-balance-between-alliance-russia-can-kasapoglu.

[13] NATO Standardization Office, Allied Joint Publication (AJP-3.2): Allied Joint Doctrine for Land Operations, Edition B, Version 1, 37. February 2022, https://www.coemed.org/files/stanags/01_AJP/AJP-3.2_EDB_V1_E_2288.pdf.

[14] Ibid., 38-40.

[15] Ibid., 38.

[16] Ibid., 39-51.

[17] NATO Defense College, “Chairman of NATO Military Committee, Admiral Rob Bauer, Visits NATO Defense College,” NATO Defense College, August 2, 2023, https://ndc.nato.int/news/news.php?icode=1937.

[18] Christopher Tuck, “The Future of Manoeuvre Warfare,” in: Advanced Land Warfare: Tactics and Operations, ed. Mikael Weissmann and Niklas Nilsson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023; online ed., Oxford Academic, April 20, 2023), 40-42, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192857422.003.0002.

[19] John Dzwonczyk and Clayton Merkley, “Through a Glass Clearly: An Improved Definition of LSCO,” Military Review, November 2023, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/Online-Exclusive/2023-OLE/Through-a-Glass-Clearly/.

[20] “Nato Alliance Experiencing Brain Death, Says Macron,” BBC News, November 07, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-50335257.

[21] NATO 2022 Strategic Concept, NATO, March 03 2023, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_210907.htm#:~:text=The%202022%20Strategic%20Concept%20describes,and%20management%3B%20and%20cooperative%20security.

[22] “British Army Sets Sail to Europe for Exercise Steadfast Defender,” British Army, February 2024, https://www.army.mod.uk/news-and-events/news/2024/02/british-army-sets-sail-to-europe-for-exercise-steadfast-defender.

[23] Can Kasapoglu, “NATO Is Not Ready for War: Assessing the Military Balance between the Alliance and Russia.”

[24] Jeroen Verhaeghe, “Is NATO Land Operations Doctrine Aiming Too High?” War on the Rocks, August 23, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/08/is-nato-land-operations-doctrine-aiming-too-high.

[25] Andrew Marshall, “What Happened to the Peace Dividend? The End of the Cold War Cost Thousands of Jobs,” The Independent, March 02, 1993, https://independent.co.uk/news/world/what-happened-to-the-peace-dividend-the-end-of-the-cold-war-cost-thousands-of-jobs-andrew-marshall-looks-at-how-the-world-squandered-an-opportunity-1476221.html.

[26] Pol Bargués, Jonathan Joseph, and Ana E. Juncos, “Rescuing the Liberal International Order: Crisis, Resilience and EU Security Policy,” International Affairs 99, no. 6 (November 2023): 2281-2299, https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiad222.

[27] H.R. McMaster, “Statement for the Record,” Senate Armed Services Committee, March 02, 2021, https://armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/McMaster–Statement%20for%20the%20Record_03-02-21.pdf.

[28] Curtis L. Fox, “Who in NATO Is Ready for War?” Military Review, July-August 2024, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/July-August-2024/Who-in-NATO-Is-Ready-for-War/.

[29] David Roza, “Why military officers are commanding fewer enlisted troops than ever before,” Task&Purpose, December 09, 2024, https://taskandpurpose.com/news/how-many-officers-in-us-military/.

[30] NATO Joint Warfare Centre, “Complexity, Adaptation, and the Evolving Character of Warfare” Three Swords Magazine36 (2020), https://jwc.nato.int/application/files/4216/0523/5386/issue36_10lr.pdf.

[31] European External Action Service, “NATO and EU: Strength through Complementarity,” European External Action Service, accessed 2024, https://eeas.europa.eu/eeas/nato-and-eu-strength-complementarity_und_fr.

[32] Center for Strategic and International Studies, “Data: NATO Responsibility Sharing,” CSIS, accessed 2024, https://csis.org/analysis/data-nato-responsibility-sharing.

[33] Charles Cooper and Benjamin Zycher, Perceptions of NATO Burden-Sharing (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1989), 20-22.

[34] David A. Ochmanek et al., Inflection Point: How to Reverse the Erosion of U.S. and Allied Military Power and Influence (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2023), https://rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2555-1.html.

[35] Matthew Savill, “A Hollow Force? Choices for the UK Armed Forces,” RUSI, accessed 2024, https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/hollow-force-choices-uk-armed-forces.

[36] Larisa Brown, George Grylls, and Aubrey Allegretti, “UK Weapon Stockpiles ‘Threadbare’ After Arming Ukraine,” The Times, September 25, 2024, https://www.thetimes.com/uk/defence/article/ukraine-western-allies-almost-nothing-left-weapon-stockpiles-z5z5v0z5j?s=35.

[37] Markus Decker, quoting Soenke Neitzel, “The Bundeswehr could probably only prove at the moment that it knows how to die with dignity,” trans. by author, Redaktionsnetzwerk Deutschland, February 02 2024, https://www.rnd.de/politik/zusammenbruch-der-ukraine-was-eine-niederlage-fuer-europa-bedeuten-koennte-RGMBM7WCXBC4TCTCPO23INPD6M.html.

[38] Jeroen Verhaeghe, “Is NATO Land Operations Doctrine Aiming Too High?” War on the Rocks, August 23, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/08/is-nato-land-operations-doctrine-aiming-too-high.

[39] Nicholas Vinocur, “Why the West Is Losing Ukraine,” Politico, February 21, 2024, https://politico.eu/article/ukraine-war-russia-why-west-is-losing.

[40] Stephen Grey, John Shiffman, and Allison Martell, “Why Ukrainian Artillery Is Outgunned by Russia,” Reuters, July 2024, https://reuters.com/investigates/special-report/ukraine-crisis-artillery.

[41] “Executive Summary: Report of the Commission on the National Defense Strategy,” Commission on the National Defense Strategy, RAND Corporation, accessed August 2024, https://www.rand.org/nsrd/projects/NDS-commission.html.

[42] Julian G. Waller, “Why Putin Is More Resilient Than You Think,” Foreign Affairs, August 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/russia/putin-resilient.

[43] Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, “Russian Military Objectives and Capacity in Ukraine Through 2024,” Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), accessed August 2024, https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/russian-military-objectives-and-capacity-ukraine-through-2024.

[44] Jake Rinaldi and Brandon Tran, “Russia’s Deepening Ties To North Korea: China’s Gateway To The Arctic?,” Modern War Institute At West Point, August 08 2024, https://mwi.westpoint.edu/russias-deepening-ties-to-north-korea-chinas-gateway-to-the-arctic/.

[45] “Duel as an Analogy to War,” created with the assistance of ChatGPT, August 2024.

[46] Christopher Tuck, “The Future of Manoeuvre Warfare,” in: Advanced Land Warfare: Tactics and Operations, ed. Mikael Weissmann and Niklas Nilsson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023; online ed., Oxford Academic, April 20, 2023), doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192857422.003.0002, accessed August 18, 2024; LtCol Gary M. Deno, “Manoeuvre Warfare Is Not Dead, but It Must Evolve,” Proceedings, U.S. Naval Institute, November 2023, https://usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2023/november/maneuver-warfare-not-dead-it-must-evolve.

[47] Octavian Manea, “The A2/AD Predicament: Challenges to NATO’s Paradigm of ‘Reassurance Through Readiness,” Small Wars Journal, September 2016, https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/the-a2ad-predicament-challenges-nato’s-paradigm-of-“reassurance-through-readiness.

[48] Amos Fox, “A Solution Looking for a Problem: Illuminating Misconceptions in Manoeuvre-Warfare Doctrine,” Armor, Fall 2017, https://www.moore.army.mil/armor/earmor/content/issues/2017/Fall/4Fox17.pdf.

[49] Christopher A. Denzel, “Achieving Decision on the Battlefield: Redefining Manoeuvre Warfare as Method, Not Philosophy,” Marine Corps Gazette, August 2022, https://mca-marines.org/wp-content/uploads/Achieving-Decision-on-the-Battlefield.pdf.

[50] Alex Vershinin, “The Attritional Art of War: Lessons from the Russian War in Ukraine,” RUSI, accessed 2024, rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/attritional-art-war-lessons-russian-war-ukraine.

[51] Carl von Clausewitz, On War, trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), accessed via Marine Corps University, usmcu.edu.

[52] Mungo Melvin, “Revisiting the Translators and Translations of Clausewitz’s On War,” British Journal for Military History 8, no. 2 (2022): 77-102.

[53] Milan Vego, “Clausewitz‘s Schwerpunkt: Mistranslated from German-Misunderstood in English,” Military Review, February 2007, armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/MilitaryReview_20070228_art014.pdf.

[54] Antulio J. Echevarria II, Clausewitz’s Centre of Gravity: Changing Our Warfighting Doctrine—Again! (Carlisle, PA: U.S. Army War College, 2002), clausewitz.com/readings/Echevarria/gravity.pdf.

[55] Michael Krause, “Clausewitz & Centres of Gravity: Open to Interpretation,” The Forge, 2021, accessed August 15, 2024, https://theforge.defence.gov.au/article/clausewitz-centres-gravity-open-interpretation.

[56] Eystein L. Meyer, “The Centre of Gravity Concept: Contemporary Theories, Comparison, and Implications,” Defence Studies 22, no. 3 (2022): 327, https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2022.2030715.

[57] John Butler, “The Godzilla Methodology: Enhancing Joint Force Planning,” Joint Force Quarterly 72 (2014): 26-30, ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/jfq/jfq-72/jfq-72_26-30_Butler.pdf.

[58] John Butler, The Godzilla Methodology: Enhancing Joint Force Planning.

[59] L. Pfeiffer, “Godzilla,” Encyclopedia Britannica, September 18, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Godzilla.

[60] Antulio J. Echevarria, “Clausewitz’s Centre of Gravity: It’s Not What We Thought,” Military Review 56, no. 1 (2003): 17.

[61] Clausewitz, On War, 92-93.

[62] Christopher Bassford, “Clausewitz’s Categories of War and the Supersession of ‘Absolute War,’” Clausewitz Studies, 20-22, December 07, 2023, https://clausewitzstudies.org/mobile/Bassford-Supersession5.pdf.

[63] Mauro Mantovani and Michel Wyss, “Schwerpunkt and the Center of Gravity in Comparative Perspective: From Clausewitz to JP 5-0,” Journal of Strategic Studies, May 2024, 1–22, doi:10.1080/01402390.2024.2349643.

[64] Mauro Mantovani and Michel Wyss, “Schwerpunkt and the Center of Gravity in Comparative Perspective: From Clausewitz to JP 5-0.”

[65] U.S. Army Field Manual 100-5: Operations (Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, 1993), https://bits.de/NRANEU/others/amd-us-archive/fm100-5(93).pdf.

[66] Douglas W. Skinner, Airland Battle Doctrine, U.S. Department of Defence, 1988, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA202888.pdf.

[67] Stephen E. Hughes, Desert Storm: Attrition Or Maneuver?, U.S. Department of Defence, 1995, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA300814.pdf.

[68] Steven Metz and Frederick M. Downey, “Centers of Gravity: Strategic Planning,” U.S. Army War College, accessed August 2024, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/January-February-2022/Metz-Centers-Gravity-1988/.

[69] Adam J. Berinsky, “Public Opinion and War: A Historical Perspective,” in: In Time of War: Understanding American Public Opinion from World War II to Iraq (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), Chicago Scholarship Online, 2013, doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226043463.003.0002.

[70] Adam J. Berinsky, “Public Opinion and War: A Historical Perspective,” in: In Time of War: Understanding American Public Opinion from World War II to Iraq (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), Chicago Scholarship Online, 2013, doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226043463.003.0002.

[71] Andrew Mack, “Why Big Nations Lose Small Wars: The Politics of Asymmetric Conflict,” World Politics 27, no. 2 (1975): 175–200, doi:10.2307/2009880. P177-178

[72] “The Tet Offensive, 1968,” U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian, accessed August 2024, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1961-1968/tet.

[73] “Viet Nam: Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger’s Search for a Strategy to End the Vietnam War,” Nixon Foundation, October 2017, https://nixonfoundation.org/2017/10/viet-nam-richard-nixon-henry-kissinger-search-strategy-end-vietnam-war.

[74] Clausewitz, On War, 87.

[75] Ibid., 93.

[76] Can Kasapoglu, “NATO Is Not Ready for War: Assessing the Military Balance between the Alliance and Russia.”

[77] “Russian Defence Ministry report on the progress of the special military operation (September 29, 2024),” Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation, https://eng.mil.ru/en/special_operation/news/more.htm?id=12530973@egNews.

[78] Heather Williams et al., “Deter and Divide: Russia’s Nuclear Rhetoric,” accessed August 2024, https://features.csis.org/deter-and-divide-russia-nuclear-rhetoric/.

[79] “Volodymyr Zelensky: Ukraine’s War for Europe,” Die Zeit, June 2022, zeit.de/politik/ausland/2022-06/volodymyr-zelensky-ukraine-war-europe-english.

[80] Volodymyr Zelensky, “May Our Collective Work Under the Victory Plan Result in Peace for Ukraine as Soon as Possible – Speech by the President in the Verkhovna Rada,” President of Ukraine-Official Website, October 16 2024, https://www.president.gov.ua/en/news/haj-nasha-spilna-robota-za-planom-peremogi-yaknajshvidshe-ob-93849.

[81] John J. Mearsheimer, “Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault,” 2014, https://mearsheimer.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Why-the-Ukraine-Crisis-Is.pdf.

[82] “Secretary Antony J. Blinken and Secretary Lloyd Austin Remarks to Traveling Press,” U.S. Department of State, accessed August 2024, https://state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-and-secretary-lloyd-austin-remarks-to-traveling-press.

[83] “Statement of the NATO-Ukraine Council,” NATO, July 11, 2024, https://nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_227863.htm.

[84] Alexandra Brzozowski, “Ramstein meeting gives birth to global ‘contact group’ to support Ukraine,” Euractiv, April 27, 2022, https://www.euractiv.com/section/defence-and-security/news/ramstein-meeting-gives-birth-to-global-contact-group-to-support-ukraine/.

[85] Barbara Moens, “EU Fumes at Rogue Viktor Orbán as Hungary’s Presidency Looms,” Politico, July 2024, https://politico.eu/article/eu-fumes-rogue-viktor-orban-hungarian-presidency-envoy-brussels.

[86] Ministry of Finance of Ukraine, “Ukraine’s State Budget Financing Since the Beginning of the Full-Scale War,” Ministry of Finance of Ukraine, accessed August 2024, https://mof.gov.ua/en/news/ukraines_state_budget_financing_since_the_beginning_of_the_full-scale_war-3435.

[87] “Ukraine Aid and House Speaker Mike Johnson’s Position on Israel and Taiwan,” CNN, April 21, 2024, https://edition.cnn.com/2024/04/21/politics/ukraine-aid-mike-johnson-house-speaker-israel-taiwan/index.html.

[88] Christopher S. Chivvis and Jack Keating, “Cooperation Between China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia: Current and Potential Future Threats to America,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 10 2024, https://carnegie-production-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/static/files/Chivvis%20Keating%20-%20Ch-Ir-Nk-Ru-Cooperation-1.pdf.

[89] Koichiro Takagi, “How the U.S. Conquered Information Warfare in Ukraine with Open Source Intelligence,” Hudson Institute, accessed August 2024, https://hudson.org/information-technology/how-us-conquered-information-warfare-ukraine-open-source-intelligence-koichiro-takagi.

[90] Marc Semo, “’Fog of War’: When Cunning Becomes a Weapon,” Le Monde, June 24, 2024, https://www.lemonde.fr/en/opinion/article/2023/06/24/fog-of-war-when-cunning-becomes-a-weapon_6036485_23.html.

[91] Samuel Charap and Khrystyna Holynska, “Russia’s War Aims in Ukraine: Objective-Setting and the Kremlin’s Use of Force Abroad,” RAND Corporation, August 2024, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2061-6.html.

[92] Chivvis and Keating, “Cooperation Between China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia: Current and Potential Future Threats to America.”

[93] Lars Lange quoting Markus Reisner, “Ukraine Has Also Achieved Successes in Recent Months,” Telepolis, August 2023, https://telepolis.de/features/Die-Ukraine-hat-in-den-letzten-Monaten-auch-immer-wieder-Erfolge-erzielt-9316350.html.

[94] Jack Watling, Oleksandr v. Danylyuk, and Nick Reynolds, “Preliminary Lessons from Ukraine’s Offensive Operations 2022-23,” RUSI, July 18, 2024, https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/special-resources/preliminary-lessons-ukraines-offensive-operations-2022-23.

[95] Robert Rose, “Biting Off What It Can Chew: Ukraine Understands Its Attritional Context,” War on the Rocks, September 2023, https://warontherocks.com/2023/09/biting-off-what-it-can-chew-ukraine-understands-its-attritional-context.

[96] David S. Fadok, “John Boyd and John Warden: Air Power’s Quest for Strategic Paralysis,” U.S. Air Force, December 1995, https://media.defense.gov/2017/Dec/27/2001861508/-1/-1/0/T_0029_FADOK_BOYD_AND_WARDEN.PDF.

[97] Olivia Garard, “Reconsidering Clausewitz on Friction,” War on the Rocks, January 2023, https://warontherocks.com/2023/01/reconsidering-clausewitz-on-friction.

[98] Theodora Ogden et al., “The Role of the Space Domain in the Russia-Ukraine War and the Impact of Converging Space and AI Technologies,” CETaS Expert Analysis (February 2024).

[99] “With Krynky Lost, What Did the Perilous Operation Accomplish?,” The Kyiv Independent, Juli 18, 2024, https://kyivindependent.com/with-krynky-lost-what-did-the-perilous-operation-accomplish.

[100] Ted Galen Carpenter, “Symposium: What does Ukraine’s incursion into Russia really mean?,” Responsible Statecraft, August 15 2024, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/ukraine-kursk-incursion/.

[101] Fabian R. Hoffmann, “The Strategic-Level Effects of Long-Range Strike Weapons: A Framework for Analysis,” Journal of Strategic Studies, May, 1–37. doi:10.1080/01402390.2024.2351500.

[102] “Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark A. Milley Hold a Press Conference,” U.S. Department of Defense, April 21, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript/Article/3370530/.

[103] Mike Dimino, “No Silver Bullet: Aid Is Not a Shortcut to Victory for Ukraine,” Defense Priorities, June 21, 2024, https://defensepriorities.org/explainers/no-silver-bullet.

[104] Howard J. Shatz and Clint Reach, “The Cost of the Ukraine War for Russia,” RAND Corporation, December 18, 2023, https://rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2421-1.html.