Abstract: As warfare has expanded to its sixth domain, the cognitive domain, securing national interests involves targeting the capabilities of the adversary instead of the adversary themselves. This evolving warfare comprises targeting every source of the adversary’s strengths (and the means that enhance it) – internal political stability; economic stability; international image; and, most recently, diplomatic partnerships with strategically important states. With increased accessibility through mass and social media, these unconventional means of warfare have become more impactful and efficient. These developments are especially concerning in the diplomatic realm since they expand the requirement of a state’s Cognitive Awareness beyond its territorial boundaries. Against this background, the case of India’s recent diplomatic endeavours getting impacted amidst exploited cognitive environments becomes relevant to the study.

Examining a sequence of relevant recent events (especially in Taiwan, Maldives, and Oman) as part of a larger cognitive war, the article highlights how cognitively exploited environments in strategically placed friendly states have impacted India’s diplomatic endeavours in contemporary times while propagating disinformation, subversion, and popular mobilisation against Indian interests.

Problem statement: How has exploiting cognitive environments against Indian interests impacted India’s diplomatic pursuits in strategically placed friendly countries as part of a larger cognitive war?

So what?: India must expand its scope of awareness in cognitive environments, including both domestically and in partner states. Having identified potential and existent threats, it must develop cognitive resilience while proactively engaging in the cognitive environments of the partner states to secure its national interests.

Diplomacy amidst Cognitively Exploited Environments

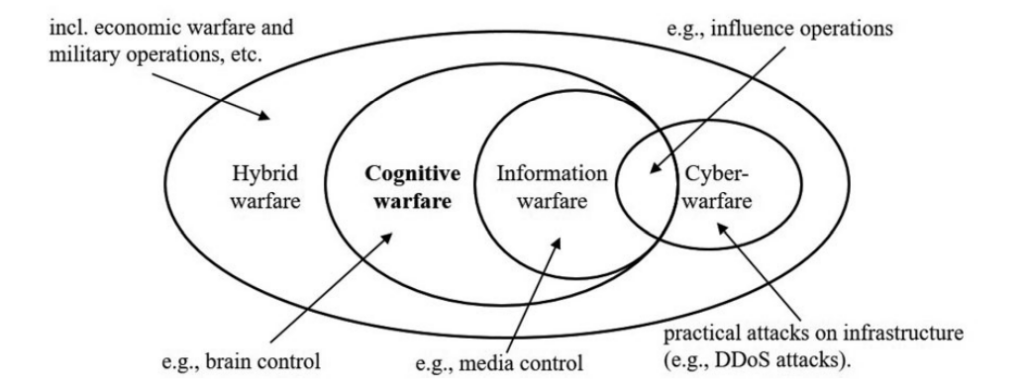

As warfare has evolved across generations and new domains have emerged, the primary goal of securing “national interests” has remained constant. However, the methods and tools to achieve these objectives have significantly transformed. The traditional boundaries between military and non-military spheres have blurred, and distinctions between war and peace scenarios have become obscured within the “grey zone.” Consequently, every individual and infrastructure is now a potential target, and wars persist even during apparent periods of peace. This phenomenon is particularly evident in the cognitive domain, the sixth domain of warfare (apart from land, air, maritime, space, and cyber). Cognitive warfare, only named recently but with historical roots predating modern warfare, is defined by some as a conceptual descendant of information and psychological warfare. In contrast, others define it as “weaponisation of public opinion by an external entity to influence public and/or governmental policy or destabilising governmental actions and/or institutions.”[1] While none of these definitions completely explains cognitive warfare, each holds some truth.

Cognitive warfare is defined by some as a conceptual descendant of information and psychological warfare.

Divergent definitions of cognitive warfare liken it to the Vedic Indian parable of blind men describing an elephant based on the part they sense – for example, to those that felt the foot described the elephant as a pillar – the definition of cognitive warfare varies across the spectrum. Collectively put, NATO defines cognitive warfare as “the activities conducted in synchronisation with other instruments of power to affect attitudes and behaviours by influencing, protecting, and/or disrupting individual and group cognitions to gain an advantage.”[2] This understanding includes elements of disinformation, psychological warfare, influence operations, cyber-operations, as well as neuroscience and engineering as tools to achieve a larger objective of brain control. The understanding consequentially distinguishes cognitive warfare from similar operations by means of its objectives and the scope it addresses. Both cognitive and information warfare, for instance, operate in the same domain. However, while information operations aim to control information dissemination, cognitive warfare attempts to control how the disseminated information is perceived.

The prevalence of cognitive warfare can be traced back at least to the 4th century BCE treatise by an ancient Indian strategist, Kautilya: the Arthashastra. While highlighting the criticality of cognitive warfare in statecraft, referring to it as Kuta Yuddha, he एकं हन्यान्न वा हन्यादिषुः क्षिप्तो धनुष्मता । प्रज्ञानेन तु मतिः क्षिप्ता हन्याद्गर्भ-गतानपि ।।” meaning, “an arrow, discharged by an archer, may kill one person or may not kill (even one); but intellect operated by a wise man would kill even children in the womb.”[4]

Unlike framing cognitive warfare solely as a response to power asymmetry, Kautilya underscores its relevance in all aspects of statecraft, particularly in diplomatic endeavours. Apart from the extensive usage of disinformation and misinformation as tools for waging a cognitive war against the adversary government’s diplomatic pursuits, the usage of segments of real information disseminated out of context proves to be an excellent strategy. In the contemporary context, this strategy, such as through leaked emails or misrepresented official communication segments, can impact public opinions and trigger popular mobilisation against a government, affecting diplomatic initiatives dependent on popular support. This strategy leaves enough vulnerable space for any adversary to exploit the cognitive environments such that popular mobilisation against a diplomatic engagement could pressure the sitting government or, worse, generate an anti-government sentiment leading to political upheaval.

The sensitive link between successful diplomatic initiatives and popular sentiment in partner states underscores the necessity for awareness of cognitive environments and potential cognitive threats from adversaries. Failure to understand domestic cognitive environments, especially in partner states, can hinder diplomatic initiatives and strain bilateral ties. Recent events with India, particularly involving Taiwan, Maldives, and Oman, among others, illustrate the importance of cognitive awareness in diplomatic engagements and the potential consequences of complacency.

Cognitive Campaign in Taiwan

In early November 2023, discussions on a mobility agreement between the Republic of China (Taiwan) and India gained prominence. Following the Official Spokesperson of the Indian Ministry of External Affairs confirming the talks on November 09, 2023,[5] a Bloomberg report the next day speculated on Taiwan hiring up to 100,000 Indians for various roles as part of the agreement.[6] By November 13, when Taipei officially acknowledged the ongoing negotiations, the Bloomberg report had circulated widely on Taiwan’s social and traditional media. Despite the Taiwanese Labour Minister, Hsu Ming Chun, refuting the claims, a popular sentiment against the potential agreement emerged, taking on a racist tone against Indians and putting the Taiwanese government on the defensive.[7] Within 15 days, both India and Taiwan were compelled to issue clarifications and engage in damage control instead of progressing with the mobility agreement. As December concluded, the current Taiwanese government categorically ruled out the possibility of such a numerically high influx and offered zero clarity on when the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) would be finalised, a response attributed to the prevailing anti-mobility sentiment influencing the government stance ahead of the then-upcoming January 2024 Presidential elections.[8] This sentiment also became a major election issue exploited by the opposition against the incumbent administration.

Within 15 days, both India and Taiwan were compelled to issue clarifications and engage in damage control instead of progressing with the mobility agreement.

Whether this was a crafted disinformation campaign or a piece of leaked, genuine information purposefully released in the public domain out of context remains unclear so far. Regardless, how this claim spread and the response it generated is worth examination. The Taiwanese government alleged that the claim regarding such a huge migrant influx that generated this panic was actually “a textbook example of cognitive warfare and information campaign.”[9] As the controversy picked up on X (formerly Twitter) and the situation heated up, reports from Taipei emerged stating that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) had a role in fueling the confusion through “modularised messages”[10] such that, out of 3,600 Facebook accounts engaging the conversation targeting the Taiwanese Ministry of Labour, over 2,000 accounts seemed to follow a set pattern.[11] The 2,000 “suspicious” accounts showed limited personal activity as if they were created for a specific purpose. [12] Moreover, one of the first articles reflecting a racist backlash against Indian migrants was published by China Times on November 14, 2023, i.e., exactly one day following the official confirmation from Taipei.[13] Quoting certain social media conversations, the article referred to the Indian migrants with racist slurs and accused them of turning Taiwan into a “sexual assault island.”[14] It is interesting to note that the media house China Times was bought by the pro-China Taiwanese tycoon Tsai Eng-Meng in 2008, and since then, its pro-Chinese Communist Party reportage has been a known fact.[15] In addition, the fact that the numerical claim entered the media discourse in Taiwan even before an official confirmation from the Taiwanese government is another striking occurrence.

The sequence and nature of these events underscore three key takeaways. First, cognitive warfare extends beyond disinformation, encompassing a broader scope. Whether information is disinformation or partial truth is inconsequential; what matters is its presentation to trigger a collective social reaction. Once triggered, organic conversations among the influenced population perpetuate the propaganda, known as ‘participatory propaganda.’ Defending against such campaigns becomes challenging, offering greater deniability to the original initiators. Second, cognitive warfare exploits pre-existing faultlines within a community. In this case, the social reaction to a potential migrant influx drew on pre-existing racist stereotypes within Taiwanese society. In cases such as this one, ensuring cognitive resilience within the home state and prompt awareness of the partner state’s cognitive environment becomes crucial.

India’s prompt awareness regarding the nature of Chinese manipulation of Taiwan’s cognitive landscape would have particularly been valuable in this context. The fact that the cognitive campaign entered the Taiwanese popular discourse early on reflects its proactive nature. A lack of appropriate cognitive awareness led to reactive responses from both New Delhi and Taipei, derailing a potentially mutually beneficial diplomatic initiative. For China, this not only turned popular sentiment against the incumbent establishment ahead of the presidential elections but also disrupted burgeoning India-Taiwan relations, which were anticipated to lead to increased economic cooperation. Hence, awareness becomes the critical first step for defence and offence in the cognitive domain. Third, this incident is not an isolated, India-centric event; it should be examined as part of a broader cognitive campaign orchestrated by China against states and their diplomatic partners perceived as detrimental to its regional and global interests. A similar scenario in the case of Maldives adds weight to this perspective.

A lack of appropriate cognitive awareness led to reactive responses from both New Delhi and Taipei, derailing a potentially mutually beneficial diplomatic initiative.

#IndiaOut Campaign and the Maldives

The newly elected government under Maldivian President Dr Muizzu took over power in September 2023, and the withdrawal of Indian troops stationed in Maldives for Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Resilience purposes was confirmed. Seventeen Indian personnel were stationed in the island nation as an accompanying contingent to two Dhruv Advanced Light Helicopters and a Dornier aircraft previously sent to the Maldives from India. This appeared to be a continuation of the raging “#IndiaOut” campaign that had driven the victory of Dr Muizzu in the September elections, consequentially marking a stark shift from the “India First” policy under the previous Maldivian establishment under President Ibrahim Solih. Notably, the campaign formed a critical issue of the 2023 presidential elections in Maldives, somewhat similar to that in the Taiwanese case. This recent development came as a wake-up call confirming the changed domestic realities in Male as well as regional dynamics in India’s neighbourhood – potentially impacting Indian regional and security interests. While the current government under Dr. Muizzu cannot neglect regional realities and the historicity of India-Maldives bilateral relations, the suggestive shift cannot be ignored. This campaign, like in the Taiwanese case, resulted from a well-crafted operation that ended up manipulating the domestic cognitive environment in the island nation – contrary to Indian diplomatic and security interests. Tracing the campaign’s trajectory becomes crucial in understanding how cognitively charged environments impacted Indian diplomatic pursuits in yet another country.

The genesis of the #IndiaOut campaign in the Maldives can be traced back to the political landscape 2013, marked by the assumption of power by Abdulla Yameen’s administration. Amid the known pro-China stance of the Yameen administration (reflected in his opaque infrastructure deals with various Chinese-owned enterprises), a conscious effort was made to sow seeds of an India-phobic environment, suggesting possibilities of India impinging on their sovereignty. Several bilateral diplomatic initiatives with India were stalled. As the elections of 2018 resulted in a change of government under President Ibrahim Solih (following public backlash over massive corruption, opaque deals with Chinese enterprises, and cases of human rights abuses by Yameen’s administration), the traditional “India First” policy was revived, and bilateral initiatives accentuated. However, the seeds of the “India-phobic” sentiment continued germinating and emerged widely after a crucial harbour agreement in 2021.

The genesis of the #IndiaOut campaign in the Maldives can be traced back to the political landscape 2013.

This crucial agreement in 2021 concerned the Uthura Thila Falu (UTF) port construction. Discourse on social media (under the hashtag #IndiaOut) and in the streets suggested that the UTF agreement was India’s attempt to impinge on the country’s sovereignty. The Indian High Commission became a focal point for expressions of this anti-India sentiment, with Indian diplomats targeted with violent threats on various social media platforms. Scrutinising the campaign, the role of a local news outlet, Dhiyares News, appears prominently. Solih’s then-ruling Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) alleged that outlet fueled the campaign, calling the #IndiaOut campaign a “well-funded, well-orchestrated, and pre-meditated political campaign” against India.[16] Adding complexity to the ongoing protests, former President Yameen (known for his pro-China tendencies), released from jail, assumed a leadership role in the ‘India Out’ campaign.

A report by the Colombo Information Agency tracked this campaign’s Twitter activity and derived crucial observations. The agency noted that 59.3k tweets using the hashtag #IndiaOut were tweeted by a mere 2,252 handles—almost half of these handles were created between 2019 and 2021.[17] Moreover, approximately half of these newly created handles were identified as fake. According to the report, around 210 handles were responsible for 80 per cent of the content engagement, including a mere eight handles that contributed to over 12,171 tweets.[18] The agency also noticed an agenda-driven content dissemination in Dhiyares News’ sister journal, The Maldives Journal. The report further highlighted the role of the co-founder of the media outlet, Azad Azaan. Of the 2,252 handles that shared the hashtag, the report noted that half of them were followers of Azaan, where his account managed to single-handedly attract 12 per cent of the total traction.[19] His pro-China stance and sympathetic attitude towards Yameen despite Yameen’s China-related corruption charges are openly visible through his social media engagement.

Viewed in a broader context, these incidents echo recent developments in Indian diplomatic endeavours within Taiwan. In both scenarios, a common thread of India-phobic sentiment prevailed, strategically exploiting pre-existing fault lines in domestic cognitive environments. While manifesting as racial animosity in Taiwan, the impact of cognitive warfare manifested as political anxiety in the Maldives. Given the strategic significance of the Maldives in the Indian Ocean region, marked by a history of Chinese debt traps and power rivalry among influential nations, concerns about external interference have been longstanding.

The impact of cognitive warfare manifested as political anxiety in the Maldives.

Even during the Yameen government, public discontent against opaque Chinese infrastructure projects surfaced but was intentionally overshadowed by the government’s promotion of India-phobic sentiments. Instead of relying on disinformation, the manipulation of real truths to shape a cognitive environment capable of sparking organic conversations translated into political upheaval. The facts and political events that were highlighted were true, but the way they were interpreted and projected played an igniting role – a classic example of cognitive warfare. While New Delhi noticed the constant manipulation of the cognitive environment, a possible failure to gauge its effectiveness on the ground ultimately resulted in a derailed bilateral relationship. This anti-India sentiment becomes particularly intriguing when considering the historical context of the India-Maldives bilateral relationship, which has seen significant milestones since Operation Cactus in 1988—an intervention by the Indian Armed Forces to safeguard the internal sovereignty of the Maldives during a military coup initiated only upon a formal request by the then-President of the Maldives.[20] Moreover, India has historically been the first responder to the Maldives’ HADR needs and is home to a large Indian diaspora contributing to its economy.

Given that New Delhi assumed that India’s story of its historical relations and contemporary interactions should be able to guard against any crafted campaigns cautions at the same aspect: lack of cognitive awareness of Male’s domestic environment. The withdrawal of Indian personnel from the nation will not only derail HADR objectives in the country but might also offer security concerns against a Chinese presence in the region. Although the funding trails have not been found so far, the evidently pro-China inclinations of the campaign have been evident and established. However, this sequence of events does not exclusively concern China. Cognitive campaigns from Pakistan have been equally detrimental. The case of Oman is an example of Pakistan’s India-centric cognitive endeavours.

Disinformation in Oman

In 2020, a tweet by an Omani royal created a stir in the relations between the populations of India and the Gulf as a whole.[21] A tweet in the name of Mona bin Fahad, Assistant Vice Chancellor of Sultan Qaboos University for International Relations and daughter of Oman’s Deputy PM Sayyid Fahd went viral, stating that if “the Indian government does not stop the persecution of Indian Muslims, then one million Indians in Oman may be expelled.” [22] The tweet came after the OIC expressed concerns over “growing Islamophobia” in India the same year.

The fake handle with 70k followers was found to be named @pak_fauj before it assumed the name of the Omani princess.[23] The fake account was traced back to Pakistan.[24] Regardless, a slurry of targeted attacks between the people of the two regions had already occurred and created mutually sour feelings. This sequence of events was followed by many other Pakistani accounts further changing their handle names to Arabic to participate and accentuate the confusion. A later clarification from the royalty stated that the offending account was fake and had been impersonating the princess on social media.[25] This incident was quite momentous since statements like the one made by the fake account tend to create threatening situations for the Indian diaspora in the region – which is the largest as compared to any other country. Triggered by an announcement from a government official, popular reactions within the population could have been provoked had the clarification from the Omani princess not come in time. Worse, triggered by the chaos, India’s relations with a crucial strategic partner (home to the strategic Duqm port) in West Asia could have been jeopardised.

Deriving Lessons for Securing Diplomatic Initiatives Amidst Cognitive Warfare

These are just isolated incidents of cognitive campaigns that could have created great damage and ended up being exposed. Various other trends have taken place in countries like Nepal, Bangladesh, and Bhutan with respect to Indian diplomatic relations with these countries lately. Moreover, cognitively disruptive activities preceding and during the G20 Summit hosted by India (especially around the event hosted in Kashmir) and those during the ongoing Israel-Hamas conflict in the background of the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) discussed during the Delhi Declaration are ongoing to impact Indian diplomacy at large. The nature of such cognitive campaigns is reminiscent of an anecdote from the Sabha Parva of the Mahabharata where facing an invincible alliance between two brothers – Sunda and Upasunda – Lord Brahma decides to create a bheda (dissension) between the two brothers in order to eliminate both of them. This dissension eventually leads the two of them to kill each other, leaving Brahma victorious without having to move an arm. The only difference in contemporary times is that this dissension is created between the population of partner states and their governments and between the populations of the other partner states.

Cognitively disruptive activities preceding and during the G20 Summit hosted by India and those during the ongoing Israel-Hamas conflict in the background of the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor discussed during the Delhi Declaration are ongoing to impact Indian diplomacy at large.

The Taiwanese reaction to the cognitive manipulation translated into an unfavourable sentiment toward the ruling Taiwanese government as well as a racist stereotype of the Indian people. A similar reaction was noticed in Maldives and Oman. In such chaos, the adversary states (China, in the case of Taiwan and Maldives, and Pakistan, in the case of Oman) had their interests secured even without proactively engaging with the partnership of India and each of these states. Since contemporary democracies are founded on popular sovereignty, this vulnerability is here to stay. Hence, three observations may be drawn in this large context.

First, the possibilities of manipulated cognitive environments are high, and these campaigns are recurring. A single defensive initiative achieving success cannot guarantee a longstanding defence. Cognitive environments must be closely monitored, and any external, motivated interferences must be closely followed. This monitoring becomes critical to ensure the sustainability of any diplomatic partnership amidst such easily exploitable environments.

Second, these attacks are pre-emptive in nature and not reactive to events in the physical domain. Every MoU is followed, and adversary states track every state visit. In order to secure their interests, as in the cases noted in this paper, China and Pakistan, the adversary states will exploit domestic cognitive environments since it offers them deniability and cheaper gains (both politically and economically) as opposed to overt operations. Narratives are crafted in the public domain by the adversaries and subtly released to grow as organic conversations – first on social media and then on the streets.

Third, countering cognitive campaigns will require understanding the expanse of these operations – not limited to disinformation and cyber operations., unlike popular belief. Portions of true information released out of context, playing on pre-existing politico-socio-economic fault lines of states, are enough to create confusion, distress, and eventual instability. The objective is not information control. The objective is brain control. Sound knowledge of pre-existing faultlines becomes integral to developing a cognitive awareness that shall be instrumental in strategising the required response.

Having observed this, India has only one option in cognitively active environments: defend and attack. The use of the conjunction and is important, because it is not defend or attack. It is defend and attack. Defence shall build on a response strategy instead of a reaction, which has been the general approach so far. As mentioned, strategising on a sound knowledge of the cognitive environments of partner countries, pro-active engagement must be undertaken. This can be ensured through greater transparency and public interaction while diplomatic initiatives are undertaken. Greater media interaction through official channels (press releases, social media announcements, op-eds in conventional media by diplomats) shall enhance information dissemination. This is crucial to develop cognitive resilience among a population that can be well equipped with official communication when cognitive campaigns target them – hence, comparatively less vulnerable.

India has only one option in cognitively active environments: defend and attack.

Regarding the offensive strategy, the scope of cognitive awareness widens to cover the information of the respective adversaries in respective regions, their objectives and capabilities, and their vulnerabilities that can be targeted. For instance, both the PRC and Pakistan are adversary states for India, but with differing objectives, capabilities, and contexts.

While the PRC’s cognitive campaigns form a part of its larger geopolitical ambitions and are better equipped to carry out those, Pakistan’s operations are exclusively India-centric. Their stakes in the partner states, thereby, differ. Differentiated responses (by forming collectives with like-minded/equally impacted countries, exposing the adversary’s links with local political class/civil society and their vested interests, or playing up their role in manipulating public opinion) shall be necessary for a comprehensive response. As India grows in stature, what is called India’s “multi-alignment” policy will expand, as it already has. Its strategic interests and economic stakes will grow, and so will its diplomatic engagements. Its geopolitical weight shall threaten several contemporaries. In doing so, ensuring acing the cognitive domain – on the defensive as well as the offensive front – shall be a defining aspect.

Tejusvi Shukla is a Research Associate at the Centre for Indian Knowledge Systems, Chanakya University, Bengaluru, India. She is also serving as a Research Analyst with the Online Indian Journal of Peace and Conflict Studies (OIJPCR). Her areas of research are focused on National Security in the Cognitive Domain. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone.

[1] Alonso Bernal et al., Cognitive warfare: An attack on truth and thought, technical report (NATO and Johns Hopkins University: Baltimore MD, USA, 2020), https://www.innovationhub- act.org/sites/default/files/202103/Cognitive%20Warfare.pdf.

[2] R. H. Scales, “Cognitive Warfare: The 21st-Century Game Changer,” Joint Warfare Centre, NATO; Joint Warfare Centre, NATO, retrieved December 27, 2023, from https://www.jwc.nato.int/application/files/7216/9804/8564/CognitiveWarfare.pdf.

[3] Tzu-Chieh Hung, Tzu-Wei Hung, “How China’s Cognitive Warfare Works: A Frontline Perspective of Taiwan’s Anti-Disinformation Wars,” Journal of Global Security Studies, Volume 7, Issue 4, December 2022, ogac016, https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogac016.

[4] 10.6.51, Full text of “The Kautiliya Arthasastra Part 1.” (n.d.), https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.326578/2015.326578.The-Kautiliya_djvu.txt.

[5] Ministry of External Affairs, India, (2023, November 10), Weekly media briefing by the official spokesperson (November 09, 2023) [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=odALpSrY4cM.

[6] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-11-10/india-plans-taiwan-labor-supply-pact-while-china-tensions-brew.

[7] Focus Taiwan – CNA English News, (2023, November 13), Taiwan, India to ink migrant worker MOU by year-end: Labor minister – Focus Taiwan. Focus Taiwan – CNA English News. https://focustaiwan.tw/business/202311130017.

[8] Ani, (2023, December 24), “No plans to bring 100,000 migrant workers from India, says Taiwan,” Mint, https://www.livemint.com/news/world/no-plans-to-bring-100-000-migrant-workers-from-india-says-taiwan-11703415946412.html.

[9] Twitter, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Taiwan, https://twitter.com/MOFA_Taiwan/status/1726881774029156779?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1726883278559629568%7Ctwgr%5E7fed9035c4372205914b6de4c17b22028d57c1d6%7Ctwcon%5Es3_&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Ffocustaiwan.tw%2Fsociety%2F202311260015

[10]台北時報, (2023, November 28); “‘Flood of Indian workers’ dismissed as Chinese rumor,” Taipei Times, https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2023/11/28/2003809832.

[11] Focus Taiwan – CNA English News, (2023, November 27), “Rumor on mass Indian worker influx China’s “cognitive warfare”: Source – Focus Taiwan,” Focus Taiwan – CNA English News, https://focustaiwan.tw/society/202311260015.

[12] Idem.

[13] 中時新聞網, & 王柏文, (2023, November 14), 10萬印度移工來台?網擔憂「恐變性侵島」 年輕人全炸鍋, 中時新聞網, https://www.chinatimes.com/realtimenews/20231114005439-260407?chdtv.

[14] Idem.

[15] “Opinion: Racism, disinformation cast shadow on India-Taiwan cooperation,” (n.d.), NDTV.com, https://www.ndtv.com/opinion/racism-disinformation-cast-shadow-on-india-taiwan-cooperation-4579209.

[16] N. Banka, “Explained: What is behind the ‘India Out’ campaign in the Maldives?,” The Indian Express, https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/the-maldives-india-out-campaign-explained-7396314/.

[17] CIA, (2021, September 21), Colombo Information Agency | Cia.lk. Home CIA, https://cia.lk/.

[18] Idem.

[19] Idem.

[20] A. Sengupta, „Operation Cactus: When India prevented a coup in Maldives,” The Indian Express, https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-history/operation-cactus-india-prevented-coup-maldives-9012435/.

[21] D. R. Chaudhury, “Fake anti-India tweet on behalf of Omani royalty: Growing trend to play spoilsport in Gulf,” The Economic Times, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/fake-anti-india-tweet-on-behalf-of-omani-royalty-growing-trend-to-play-spoilsport-in-gulf/articleshow/75301807.cms.

[22] Idem.

[23] S. Sharma, “Fact Check: Did Omani Princess Mona threaten to expell Indians over “persecution of Muslims” in India?,” IBTimes India, https://www.ibtimes.co.in/fact-check-did-omani-princess-mona-threaten-expell-indians-over-persecution-muslims-india-818145.

[24] S. Sibal, “Pak account poses as Omani princess tweets anti-India material; princess clarifies,” WION, https://www.wionews.com/india-news/pak-account-poses-as-omani-princess-tweets-anti-india-material-princess-clarifies-294086.

[25] Idem.