Abstract: NATO’s defence concept in the central region called for the Forward Defence close to the Iron Curtain during the Cold War. The aim was to achieve superiority through fire and movement through a manoeuvrist approach: manoeuvre combined with attritional effects. How this was to be achieved in battles of combined arms was assessed differently in the troop-contributing nations and within the NATO Command Structure. This led to discussions among concerned military authorities until harmonisation was reached shortly before the end of the Cold War.

Problem statement: In which way did the implementation of “Forward Defence” endanger a cohesive defence?

So what?: After some discussions between NATO commands and the United Kingdom and after some doctrinal improvements, restructuring and modernisation significantly reduced risks. The issue of limited space for manoeuvre remained principally critical. It should be avoided in similar circumstances in the future—whenever possible.

Source: shutterstock.com/Skorzewiak

Defend and Deter

NATO’s mission to deter as well as to prepare for war required a common strategy, doctrine, and warfare concept as well as sufficient capabilities.[1] Concerning warfare concepts, two different approaches or a mixture of both were theoretically available: attritional or manoeuvre warfare. In NATO in the 1970s and 1980s, a manoeuvre approach to warfare was chosen for planning a Forward Defence.[2] Taking the meaning of Forward Defence too literally, this design of a defence might not have led to the desired strategic outcome.[3]

NATO’s mission to deter as well as to prepare for war required a common strategy, doctrine, and warfare concept as well as sufficient capabilities.

Definitions

Warfare is the overarching term for different styles of conducting war. Warfare can be seen as the continuum from highly attritional at one end and non-attritional at the other. The purpose of both is to defeat an enemy or at least terminate hostility.[4]

Attrition is a reduction of personnel and material in a military formation. It is the gradual reduction of the capabilities of an adversary through sustained military pressure. Its primary factor is the depletion of combat power. Often, it is figured to be the most literal form of armed strategic competition. An attritional approach is mainly characterised by using direct action from positions or fortifications with little movement and less mobility, but protection against weapons effects and massive firepower.[5] It might be leveraged until preconditions for manoeuvre are being realised.

Manoeuvre was defined in NATO’s Allied Tactical Publication (ATP) 35 in the 1970s: “By manoeuvre, a commander attempts to position his force in such a way; to gain an advantage over an enemy… manoeuvre is comprised of two elements: fire and movement. Both are essential and must be integrated… to preserve… freedom of action and achieve success.”[6] Since then, the term has become NATO’s “land component operational philosophy”: manoeuvre emphasises targeting enemy morale, its overall cohesion and will to fight. All available means within all domains are to be combined. In combat, the manoeuvrist approach includes elements of movement, fires and defence. Mobility of troops, as well as troops in defensive positions, are leveraged. Speed, momentum, deception of actions and surprise are used to confuse an enemy and wear him down ultimately. Doctrinally, the implementation of manoeuvre warfare requires a minimum of human resources and materiel.[7]

Manoeuvre is comprised of two elements: fire and movement.

The exploitation of both styles, attrition and manoeuvre, can be traced back in military history. Numerous military theorists and practitioners analysed the characteristics, the pros and cons, effects and perspectives of both. Military leaders implemented one or the other depending on their respective situation, resources, opposing forces, time and space.[8] During a war, the approaches of warfare might change in one or the other due to operational and/or tactical developments.[9] It seems that manoeuvre was and is still the warfare style of choice in NATO.[10] An implementation of a manoeuvrist approach in NATO’s defence concepts was accompanied by disputes on applicable tactics and operational concepts.

NATO Strategy and Forward Defence

While the first strategic concepts of NATO were more attrition rather than manoeuver orientated, the strategy of Flexible Response from 1967 onwards favoured a manoeuvrist approach.[11] The strategy of Flexible Response served as a deterrence as much as it was a method of warfighting. The alliance experienced a breakdown in diplomacy and subsequent armed escalation, conventional warfighting would be exhausted before the employment of nuclear weapons. The strategy consisted of responses to any armed aggression in three steps: (1) Direct Defence, (2) Deliberate Escalation and (3) General Nuclear Escalation.[12] Direct Defence should be conventionally performed in the style of manoeuvre warfare. Therefore, the first doctrine document, ATP 35, addressed manoeuvre as one of its principles of land warfare.[13]

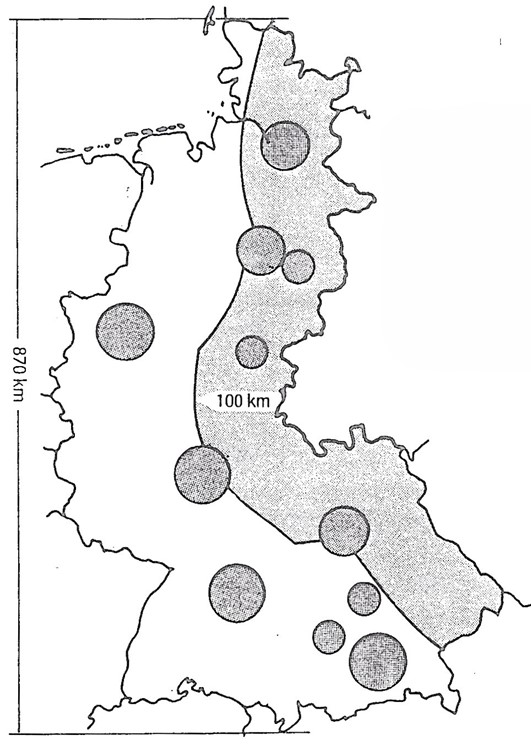

Major cities, urban terrain and industrial areas stretched between 50 and 100 km west of the Inner-German Border; Source: author.

Forward Defence was a political-military obligation as part of the Flexible Response strategy and binding requirement for defence planning in NATO and troop-contributing nations. Forward Defence required conventional warfare close to the Inner German border (IGB). All NATO-nations agreed on this guidance. The rationale for directing Forward Defence was to prevent the Federal Republic of Germany, with its operationally limited depth, from becoming a battlefield across its whole territory. Major cities, urban terrain, and industrial areas stretched between 50 and 100 km west of the IGB, and the Iron Curtain had to be kept out of the battle as much as possible.[14]

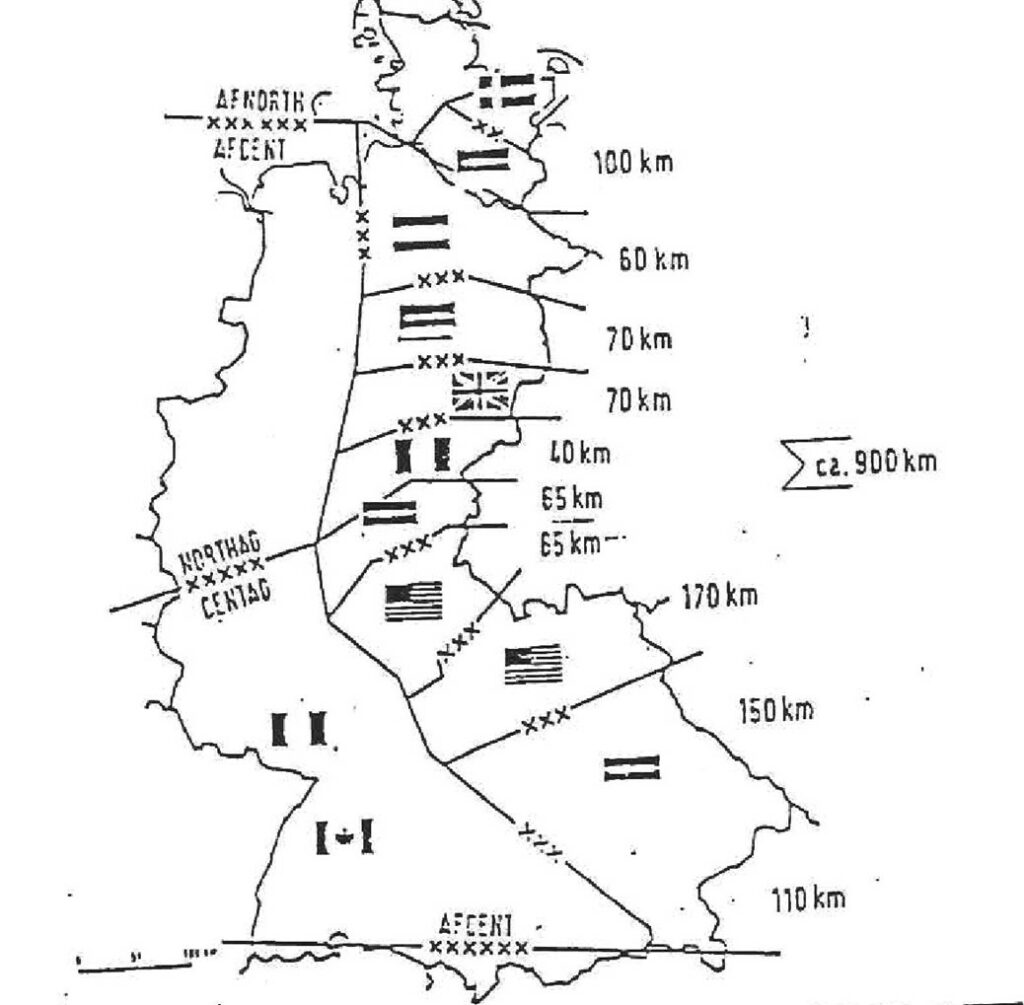

NATO’s Forward Defence in the central region was organised by allocating defensive areas to each of the eight earmarked corps. In case of war, one corps each was provided by the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Belgium. In addition, U.S. earmarked two, Germany three corps. The command was divided into two Army Groups, Army Group North (NORTHAG) and Army Group Central (CENTAG), each with four corps. NORTHAG planned and controlled operations of the 1 (NL), 1 (GE), 1(UK) and 1 (BE) Corps; CENTAG the 3(GE), 5 (US), 7 (US) and 2(GE) Corps. The overall design for land warfare was called “layer cake”. Corps defence areas were called “boxes”.[15]

NATO’s Forward Defence in the central region was organised by allocating defensive areas to each of the eight earmarked corps.

NATO Central Region – NROTHG / CENTAG and corps defence areas, called “Layer cake” with its corps-“boxes”; Source: author.

The dimensions of these boxes were determined by terrain, probable enemy approaches and available major formations. Corps width ranged between 40 to 70 km. Divisions within those corps had to defend up to 35 km width, conceptionally between 12 and 20 km and a depth of 40 km.[16] Three mechanised divisions with three brigades each were deployed in a corps box.[17] Operations of forces within the boxes included delay, holding terrain and counterattacks. NORTHAG’s defence, for example, was expected to face a staggered attack by at least seven armies into the North German Plain.[18]

Principles of NATO’s Land Warfare

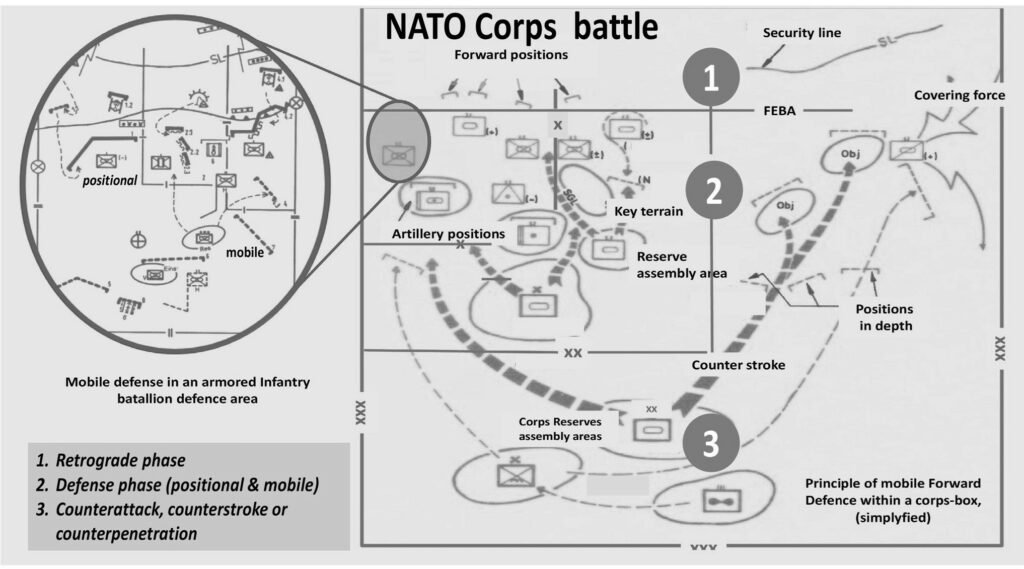

Fighting was determined by mobile combat, leverage of fire, obstacles and terrain features. Static fighting positions were to hold terrain features, preventing being taken by an attacker and enabling counterattacks of forces. Forward Defence in a corps defence area was foreseen in three principal phases:

- A retrograde battle was to be conducted by about one-third of combat and supporting troops with fire and movement. The main tasks were to detect the enemy’s approach, intentions and strength, to deceive them about defence positions, and to attack them as much as possible without major losses. The tactical manoeuvre was characterised by temporary positional defence combined with local counterattacks. Retrograde combat aimed to gain time for units deployed in depth at a defence line to establish their positions and barriers. The retrograde should last at least 24 hours before the enemy could reach the main defence line. Space was thus traded for time. The delaying zone stretched between 5 and 30 km west of the IGB. After delaying, troops were foreseen as a reserve and regenerated.[19]

- The defence battle was conducted along a Forward Edge of the Battlefield (FEBA). The FEBA was centrally determined by NATO Central Region Command (AFCENT), consisting of a virtual line from north to south running parallel to the IGB between 5 and 30 km and coincided with the delaying zone. The FEBA served as a major coordination line, enabling cohesive defence. Along the FEBA, about two-thirds of corps combat formations should be deployed. According to the Forward Defence concept, an enemy attack should be blocked at the FEBA. They should be defeated by fire and counterattacks of available local reserves without giving up further space. Local counterattacks served to close enemy incursions into FEBA positions. A major concern of corps and division commanders was the risk that an attacker penetrated between two corps trying to envelop formations still fighting at the FEBA. Therefore, it was intended to prevent deep penetration westwards by all means.[20] The main determinants for defence at the FEBA were the geography of the battlespace, the opponent’s approach with their identified weaknesses, the own capabilities on land and in the air for fire and movement, as well as the cohesion within and between the defence boxes.[21] Forces along the FEBA in a positional posture behind natural obstacles or artificial barriers were the cornerstones enabling the cohesion of the defence.[22] Barriers were designed to slow down and channel the enemy for targeting as well as determine where battles were to be fought. During the defence phase, dismounted combat troops were fighting from field positions in urban sprawl, forest areas, and along waterlines. Enemy forces slowed down or stopped were to be destroyed by artillery fire and/or by short-ranging counterattacks in their flanks or rear. Due to the Forward Defence concept, limited space was available for counterattacks. Manoeuvre was executed by making short “hooks” (pincer movements) or local forward “counter-attacks” to defeat the enemy at the FEBA.[23] Anti-tank helicopters and Close Air Support of the NATO Air and Army Aviation Forces mainly supported the fight against enemy bridgeheads, tank concentrations or advancing enemy Operational Manoeuvre Groups (OMG).[24] Important sections of terrain (“key” terrain) in the depth of the corps area were supportive of rapid action of the enemy, as well as for own operational counterattacks. Key terrain was determined at the divisional, corps, and army group levels. This terrain was to be denied to the enemy under all circumstances and leveraged through manoeuvre in moments of opportunity. If there were indications of the opponent’s breakthroughs through the FEBA and beyond, a limited withdrawal might have been accepted until a counterattack of operational reserves of the corps or army groups had been executed. Determining the terrain for defence and the deployment of reserves posed high risks of failure. Taking such risks influenced the chances for success of manoeuvre warfare.

- Counterattacks of major reserves from corps or divisional level should hold against a major breakthrough in the corps depth to regain lost terrain and support a neighbour corps against an enemy breakthrough. At the army group level, reserves in the 1970s were very limited to cope with all likely enemy’s penetrations. Tactical nuclear escalation became an option if all operational reserves of the army groups were committed.[25] The execution of the nuclear option was uncertain due to necessary political decisions and expected damage. Therefore, nuclear escalation should be avoided as long as possible. However, due to conventional quantitative superiority of the Warsaw Pact Treaty (WTO), nuclear escalation remained an option in NATO, mainly for deterrence or critical developments during hostilities.[26]

Source: author.

Application of Manoeuvre

Manoeuvre principally remained the preferred choice in NATO’s Forward Defence concept, enabling the outnumbered forces to fight successfully. Limited capabilities and gaps were to be compensated by tactical superiority at all levels: This included exploiting terrain features, speed, momentum, synchronisation of fire, feints, deception and disruption of the enemy’s command and control structure. The intention was to execute this in a limited space close to the IGB. Decentralisation of command, mission command and superior leadership were envisaged as the appropriate means of warfare.[27] This all was understood as a manoeuvrist approach when implementing Flexible Response together with Forward Defense in NATO.[28]

Limited capabilities and gaps were to be compensated by tactical superiority at all levels.

However, the overarching political-strategic goal was leveraging the style of manoeuvre warfare to bring any aggressor as fast as possible “to the negotiating table” and to abandon offensive intentions. It would limit the damages if this goal could be achieved during the first days after the beginning of hostilities. This aspect was already part of peacetime deterrence politics to prevent armed hostilities between NATO and the WTO from the outset.[29]

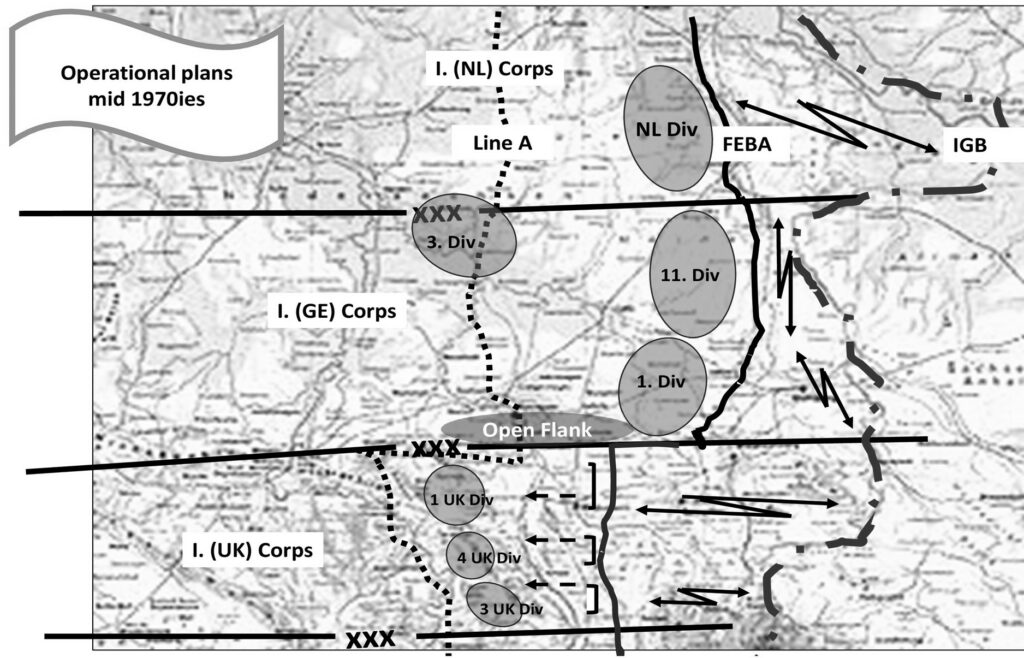

The rationale for disputes: The operational setting in the Northern Plain, creating an open flank between the German and British corps; Source: author.

Disputes

Against WTO superiority, defence plans of the corps in the 1970s showed problems in implementing the NORTHAG operations plan. While NL, GE and BE corps considered more or less the NORTHAG’s intentions for a Forward Defence along the directed FEBA in their plans, the 1 (UK) Corps remained planning to defend further west at the Weser River and to extend the retrograde operation from the IGB to Weser. After critique and pressure, the 1 (UK) corps eventually changed its defence line further east as directed by NORTHAG.[30]

Source: author.

Still unacceptable plans of I (UK) corps were revealed in 1975 with the study “Harmonisation of Battle Plans” by NATO Allied Forces Central Command Europe (AFCENT).[31] A new critique focussed on the retrograde formations, which were fewer than one-third of combat troops, as foreseen: Only two reconnaissance battalions were planned for employment instead of two brigades in the retrograde sector of about 60 km width. These formations were too few compared with the purpose of retrograde operations. In addition, very limited forces were deployed along the FEBA, which – instead of a tenacious defence – would virtually “continue the previous retrograde”.[32] The bulk of British divisions was kept ready at a further depth. The British intention was to conduct a short retrograde only to verify the enemy’s strength and direction of attack. During the defence battle phase at the FEBA, a kind of retrograde operation would be continued, drawing the attacking enemy deeper into the defence area where staggered “killing zones” were prepared. There, the attacker should be blocked and defeated by heavy fire.[33] This kind of operation would create a problem, leading to an open flank of the northern I. (GE) Corps of about 40 km. The British assumption was that the enemy would be quickly defeated in these killing zones. This would happen then before an attacker could threaten the open flank. Identifying this risk, the 1 (GE) Corps was alerted and took the problem to NORTHAG and AFECNT levels.[34]

The British NORTHAG commanders, as well as the British Chief of the General Staff (CGS), were asked by the Commander in Chief of AFCENT to influence the respective British corps commanders to adapt their plans in line with the Forward Defence rationale. A first enhancement resulted in 1977, when a divisional headquarters was then allocated to control the retrograde phase. To avoid a too rapid withdrawal, the Commander of NORTHAG took control over the retrograde phase of the corps, which was delegated to the corps level before. The British Corps objected to the directive to plan more formations along the FEBA. It continued to foresee killing zones in the corps area depth.[35]

To avoid a too rapid withdrawal, the Commander of NORTHAG took control over the retrograde phase of the corps, which was delegated to the corps level before.

General Sir Nigel Bagnall signing the NORTHAG GDP 1984; Source: author.

When Lieutenant General Sir Nigel Bagnall took command of 1. (UK) corps in 1981, he also supported a decisive corps battle in depth. Nevertheless, he then initiated a variety of reforms to implement a much more manoeuvrist approach, which he principally favoured. He introduced mission command on levels below brigade. Further changes were an extended officers training with study periods, map exercises and terrain recce as well as learning to exploit opportunities posed by the enemy.[36] He strongly promoted the swift realisation of the British Corps reorganisation into three tank divisions with three brigades.[37] At the same time, a supportive capability enhancement occurred by fielding the new Challenger armoured fighting vehicle and Warrior armoured personnel carrier, as well as new artillery systems and antitank helicopters. On his initiative, more combat and enabling units were earmarked in the UK for employment within 1 (UK) corps. He improved the conditions to fight the decisive battle in the depth of the corps area, but in a smarter and more mobile manner, requiring speed and momentum as well as stable liaison to the 1(GE) Corps.[38]

Still, he remained very critical concerning Forward Defence “being over-literal interpreted.”[39] Restrictions to fight too far forward would undermine effective manoeuvre. He was the first corps commander to demand a more precise specification of Forward Defence from AFCENT. As long as the problem of different interpretations of Forward Defence existed, a cohesive defence along the FEBA remained endangered and critical.[40]

When, in 1983, Bagnall took over command of NORTHAG, he assessed that the concept of the corps battle was inadequate to halt and defeat massive enemy formations. The availability of only one division as NORTHAG’s operational reserve for counterattacks was unsatisfactory. Therefore, he extended the NORTHAG operational reserve from one to four divisions, “putting a string” on the corps reserves of 1 (NL), 1 (GE) and 1(UK).[41] This enabled NORTHAG to conduct an additional battle in case the corps battles failed, and the enemy could employ his second operational echelon forces. Bagnall defined this as a three-phase battle consisting of a retrograde, the corps defence battle and the army group battle.[42] After some discussions at NATO and national levels, the NORTHAG concept was accepted at AFCENT. Restricting probable damage in the Federal Republic of Germany, the battlefield was extended into enemy territory by more far-reaching fire from ground and air. It was not intended to cross the IGB with combat formations on the ground. AFCENT lowered the dogmatic and binding manner by a new directive. Finally, the 1 (UK) Corps’ GDP from 1989 complied with Forward Defence. The dispute was solved due to an AFCENT directive with a clarification and various improvements of 1 (UK) Corps.[43]

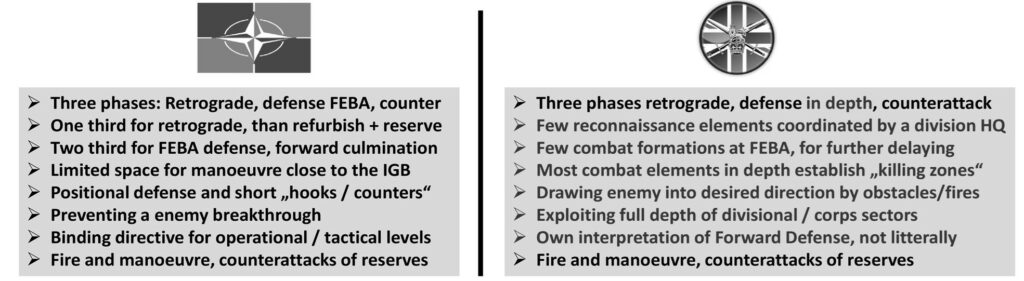

Major differences between NATO and British approach to Forward Defence, being solved int the 1980ies; Source: author.

Conclusions

With the disclosure of operational plans and disputes after the Cold War, it becomes clear that the NATO policy concept of Forward Defence clashed with the British understanding of manoeuvre warfare.[44] In British eyes, the literal implementation of Forward Defence without precise guidance significantly restricted manoeuvre and would lead to attrition. The delaying sector and the allocated FEBA offered insufficient space for manoeuvre from a British point of view. The approaches of 1 (GE) and 1 (NL) Corps to conduct a mobile battle with short-ranging counterattacks supported by the positional defence at the FEBA did not convince the British planners. On the other hand, the British Corps of the 1970s suffered from weaknesses such as lack of modernisation, adequate staff officers training, insufficient divisional structures and low degree of mobility, which hampered to conduct adequate manoeuvre.[45] Improvements in the 1980s enabled all Corps and NORTHAG to increase their manoeuver capabilities.[46] Most Improvements were observed by the WTO, which became very concerned.[47]

With the disclosure of operational plans and disputes after the Cold War, it becomes clear that the NATO policy concept of Forward Defence clashed with the British understanding of manoeuvre warfare.

At the end of the Cold War, the British published their first doctrinal document for the operational level, recommending the art of manoeuvre warfare.[48]

The dispute showed that

- defence, especially with a manoeuvrist approach, requires a minimum of forces and an appropriate structure, of which the 1 (UK) Corps was short in the 1970s. After restructuring, the extension of mechanisation and modernisation, the posture to conduct manoeuvre warfare was significantly improved;[49]

- political originated strategies such as Forward Defence require clear directives to be implemented, especially in alliances where different military cultures are to be considered;[50]

- a conceptualisation of manoeuvre warfare needs more than a short definition as outlined in the ATP 35 and ATP 35 A.[51]

However, the extent to which this concept of Forward Defence combined with a manoeuvre-centric approach would have led to the desired success remains open since political conditions did not lead to an armed conflict in Europe and thus to its application.

Initiated by disputes on the British manoeuvre approach during the Cold War, its definition and principles were reviewed and led to the current doctrine for land warfare in NATO’s AJP 3-2. Preconditions to successfully implement a manoeuvre approach in land warfare are:

- “smart mental mobility”;

- knowledge of the enemy intention to exploit his weaknesses,

- tactical mobility and firepower to prevent attrition;

- speed and action to overload the enemy through information, changing his initiative to reaction;

- space and terrain for manoeuvre; and

- support in all relevant domains.

The historical example teaches that the literal implementation of political catchwords sometimes might lead to problematic effects and disputes. Strategies should be understandable, short and have agreed terms along with sufficient resources. In the case of political-strategic guidance with negative effects on own troops, it might be recommendable for senior military authorities to wrestle with their political masters to ensure political aims are not being achieved at the expense of the fighting soldier and population. Ultimately, such a strategy could endanger both the achievement of political goals and military success. On the other hand, critical circumstances in implementing a strategy must be compensated or reduced by explaining the rationale behind it and ensuring appropriate resilience, enablement, and posture.

Currently, the question arises as to whether and how the new NATO strategic concept decided at Madrid 2022 and outlined in proposals at Vilnus 2023 will create problems such as Forward Defence in Eastern Europe again or not. For the defence of Eastern Europe, the military-political question arises for NATO and the concerned nations: what kind of manoeuvre warfare can be envisaged if manoeuvre space is again limited and war damage has to be prevented.[52]

The Russo-Ukrainian war from 2022 until today shows that both sides tried several times to devise a manoeuvrist approach. This was followed by several changes to attrition and then back to manoeuvre. Competition to regain the initiative and leverage opportunities in all domains, as defined in the manoeuvrist approach, is observed every day.[53]

Friedrich Karl Jeschonnek, Colonel German Army (retired), Military-historical Research, mainly Cold War Operational & Tactical Concepts and War planning. Examples Publications (2023/2024 only): NORTHAG Operational Planning, in: ÖMZ 6/2023; The Polish War plan of 1964, in: MGZ 1/2024; History of War Planning, in: Clausewitz-Jahrbuch 2022/2023; Competences: Military History, Economics, Operations Research. The views contained in this article are the authors alone.

[1] Gregory W. Pedlow (Ed.), “NATO Strategy Documents 1949-1969,” (NATO, Brussels, 1997), MC 48/3, para 5.d., 376.

[2] John Kiszley, “The meaning of manoeuvre,” Rusi-Journal, 142, Nr.6 (1998), 37.

[3] Helmut R. Hammerich, “Halten am VRV oder Verteidigung in der Tiefe? Die unterschiedliche Umsetzung der NATO-Operationsplanungen durch die Bündnispartner,“ in: Heiner Möllers/Rudolf J. Schlaffer, „Sonderfall Bundeswehr,“ Streitkräfte im nationalen und internationalen Vergleich, (De Gruyter, München 2014), 92-93; Torsten Squarr, “Operative Beweglichkeit im Raum unter den Rahmen-bedingungen der grenznahen Vorneverteidigung – ein Zielkonflikt,“ (Thesis at the German Defence College, Führungsakademie, Hamburg 1988).

[4] NATO Standardization Office (Ed.), “Allied Joint Doctrine for Land Operations,” AJP-3.2, STANAG 2288, (Brussels, February 03, 2022), accessed August 02, 2024, https://coemed.org/files/stanags /01_AJP/AJP _3.2_EDB_VI._E_2288/html.

[5] Trevor Depuy, “Attrition: Personal Casualties,” in: Trevor N. Dupuy (Ed.), „International Military and Defence Encyclopedia“ – [IMADE], vol. 4 M-O, (Brassey’s US, Washington/New York 1993), 318-319.

[6] John Kiszley, “The meaning of manoeuvre,” Rusi-Journal, 142, Nr.6 (1998), 36-37; William S. Lind, “Manoeuver,“ in: Trevor N. Dupuy (Ed.), IMADE, vol. 4 M-O, (Brassey’s US, Washington/ New York 1993), 1611-1614; NATO-Military Agency for Standardization (NATO-MAS), Allied Tactical Publication 35 A, “Land Force Tactical Doctrine,” (ATP 35 A), (NATO, Brussels, 1978), 1-5; ATP 35 and ATP 35 A describe the NATO understanding of Manoeuvre during the Cold War. At that time Manoeuvre and Mobility were defined as connected terms. Mobility supports manoeuvre warfare.

[7] NATO Standardization Office (Ed.), “Allied Joint Doctrine for Land Operations,” AJP-3.2, STANAG 2288, (Brussels, February 03, 2022), Chapter 3 – Fundamentals, Section 1 – the manoeuvrist approach, accessed August 02, 2024, https://coemed.org/files/stanags /01_AJP/AJP_3.2_EDB_VI._E_2288/html, 37-42.

[8] Robert Greene, “The 33 Strategies of War,“ (Viking, London 2006), 253-270.

[9] John Kiszley, “The meaning of manoeuvre,” Rusi-Journal, 142, Nr.6 (1998), 36.

[10] NATO-Military Agency for Standardization (NATO-MAS), Allied Tactical Publication 35 A, “Land Force Tactical Doctrine,” (ATP 35 A), (NATO, Brussels, 1978), 37-42.

[11] John Kiszley, “the meaning of manoeuvre,” Rusi-Journal, 142, Nr.6 (1998), 37.

[12] Gregory W. Pedlow (Ed.), “NATO Strategy Documents 1949-1969,” (NATO, Brussels, 1997), 3-45 to 3-70.

[13] NATO-Military Agency for Standardization (NATO-MAS), Allied Tactical Publication 35 A, “Land Force Tactical Doctrine,” (ATP 35 A), (NATO, Brussels, 1978).

[14] Wilhelm Hetzel, “Die militärpolitische Situation in der Gesamtverteidigung am Beispiel der Bundesrepublik Deutschland,“ Zivilschutz, 30, Heft 3 (März 1966), 79-80; David Isby and Charles Kamps, “Armies of NATO’s Central Front,“ (Jane’s, London 1985), 173.

[15] Hugh Faringdon, “Strategic Geography, NATO, the Warsaw Pact and the Superpowers,” (Routledge, London and New York 1989, 2nd Ed.), 358-373.

[16] Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv [BAMA], BW 2/27233, “Operative Minima und Kräfteaufwuchs von War-schauer Pakt und NATO,“ February 22, 1988, 3, Illustration 2.

[17] Gert Bolik, “NATO-Planungen für die Verteidigung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland im Kalten Krieg,“ (Miles, Berlin 22023),129-134; Exception was the I. (BE) Korps, which had to defend 40 km of FEBA with two Divisions and a regimental recconnaissance force of three battallions, Association Atlantique Belge (Ed.) „La Belgique et L‘OTAN”, (Brussels 1978), 48-59.

[18] The WTO planned to deploy against NORTHAG, elements of two fronts including 7 armies in two operational echelons as part of the First Strategic echelon, followed by at least two or three further mobilised fronts from Russian terrain. Siegfried Lautsch, “Kriegsschauplatz Deutschland, Erfahrungen und Erkenntnise eines NVA-Offiziers,“ (ZMSBw, Potsdam 2013), 111-116, 146-147; Hans-Werner Deim, Hans Georg Kampe, Joachim Kampe, Wolfgang Schubert, “Die militärische Sicherheit der DDR im Kalten Krieg, Inhalte, Strukturen, Verbündete, Führungssstellen und Anlagen,“ (Verlag Dr. Erwin Meißner, Hoppegarten 2008), 39-43, Schema 2 – 4.

[19] Eike Middeldorf, “Führung und Gefecht, Grundriß der Taktik,“ (Bernhard & Graefe, Frankfurt am Main, 1968, 2nd Edition).

[20] NATO-Military Agency for Standardization (NATO-MAS), Allied Tactical Publication 35 A, “Land Force Tactical Doctrine,” (ATP 35 A), (NATO, Brussels, 1978), 3-24 to 3-30.

[21] Gerd Bolik, Heiner Möllers, “Eine Black Box. Anmerkungen zu den Verteidigungsplanungen der NATO (1960-1990),“ in: Johannes Bergmann, Paul Fröhlich, Gundula Gahlen, (Ed.), VI. Teil: „Krieg in der Ukraine, Themenschwerpunkt Krieg in der Ukraine. Militär- und Gewaltgeschichtliche Hintergründe,“ (Portal Militärgeschichte 2022), accessed August 02, 2024, DOI: https:77doi.org/1015500/akm.09.05.2022.

[22] BAMA, Bw/2/52911, BMVg, Fü H III 1, Tgb.Nr. 6596/77 geh., 11.02.1977.

[23] Bernd Hospach, “Die Technik der Landminen verlangt eine dynamische Taktik,“ Europäische Wehrkunde 36 (Nr 3,1987), 165-168.

[24] The WTO / Soviet Operational Manoeuver Groups (OMG) consisted of a reinforced division on army level that exploited an achieved breakthrough to rapidly attack the enemy’s rear and create havoc. The OMG concept was developed in the 1930s and reintroduced about 1980. Christopher N. Donally, “Die operative Manövergruppe, eine neue Herausforderung für die NATO,“ Internationale Wehrrevue 15, Nr 9 (1982), 1177-1186.

[25] John Kiszley, “the meaning of manoeuvre,” Rusi-Journal, 142, Nr.6 (1998), 37.

[26] European Security Study Group (Ed.), “Strengthening Conventional Deterrence in Europe, Proposals for the 1980s,” (St. Martin’s Press, New York 1983), 7-12.

[27] John Kiszley, “The meaning of manoeuvre,” Rusi-Journal, 142, Nr.6 (1998), 37-38.

[28] A General Defence Plan (GDP) was the operational plan for all NATO levels. After implementation in tension and crisis, GDP served as an order for the execution of deployment and initial operations. It described the expected situations, intentions, objectives, force composition, concept of operations in a designated area, missions of subordinate formations, and organisation of support and command arrangements. It adheres to NATO strategy concepts. A GDP was formatted following NATO – STANAG 2014. Friedrich Jeschonnek, “Militärische Einsatzplanungen, Vom Instrument der Kriegführung zum Mittel von Abschreckung und Kriegsverhütung,“ Clausewitz-Gesellschaft, Jahrbuch 2022-2023, (Hamburg 2023) Band 18, 214-246.

[29] Hans-Heinrich Weise, “NATO Policy and Strategy,” in: IMADE vol. 4 M-O, (Brassey’s US, Washington/New York 1993), 1913-1922.

[30] Helmuth R. Hammerich, “Halten am VRV oder Verteidigung in der Tiefe? Die unterschiedliche Umsetzung der NATO-Operationsplanungen durch die Bündnispartner,“ in: Heiner Möllers/Rudolf J. Schlaffer, “Sonderfall Bundeswehr, Streitkräfte im nationalen und internationalen Vergleich,“ (De Gruyter, München 2014), 92-93; 81-112.

[31] Idem.; BAMA BW/2/52911, Memo BMVg Fü H III 1 to Fü S III 6, dated 11.02.1977, on the AFCENT – Study, “CINCENT’s Report on Rationalisation of the Forward Ground Defence Concept in the Central Region,” AFCENT 1220/01/049/77 January 24, 1977.

[32] The National Archives [UK] File DEFE 70/1276, [Period 1977-1982, subject BAOR, Forward Defence].

[33] Colin McInnes, “Hot war, Cold war, the British Army’s Way in Warfare 1945-95,” (Brasseys, London / Washington 1996), 55-60.

[34] Helmuth R. Hammerich, “Halten am VRV oder Verteidigung in der Tiefe? Die unterschiedliche Umsetzung der NATO-Operationsplanungen durch die Bündnispartner,“ in: Heiner Möllers/Rudolf J. Schlaffer, “Sonderfall Bundeswehr,“ Streitkräfte im nationalen und internationalen Vergleich, (De Gruyter, München 2014), 92-93; 81-112.

[35] Various Commanding Generals of 1 (UK) Corps between 1974 and 1989 discussed the issue outside files and letters. The first who’s reactions were documented was in 1980 Lieutenant General Sir Nigel Bagnall (1927-2002), later UK Field Marshal. He was Commanding General I. (UK) Corps from 1979 to 1982, Commanding General of NORTHAG from 1982 to 1985, Chief of General Staff from 1985 to 1988. Tony Heathcote, “The British Field Marshals 1936-1997,” a biographical dictionary, (Pen&Sword, Barnsley 1999, reprint 2012), 35-37; John Kiszley, “The British Army and Approaches to Warfare since 1945,” Journal of Strategic Studies, 19 (1997, 4), 179-206.

[36] Nigel T. Bagnall (Ed.), “1st British Corps Battle Notes,” (45309 G 3 EPS, Bielefeld 1981), Chapter 3.

[37] Richard Dannatt, “Boots on the Ground, Britain and her Army since 1945,” (Profile Books, London 2016), 185.

[38] John Kiszley, “The British Army and approaches to warfare since 1945,” Journal of Strategic Studies, 19 (1997-4) 198-200.

[39] The National Archives [UK] File DEFE 70/1276, [Period 1977-1982, subject BAOR, Forward Defence].

[40] John Kiszley, “The British Army and approaches to warfare since 1945,” Journal of Strategic Studies, 19 (1997-4), 199.

[41] Friedrich Jeschonnek, “Die NORTHAG-Operationsplanung im Wandel der 1980er Jahre: Operatives Denken im Kalten Krieg,“ Österreichische Militärische Zeitschrift [ÖMZ] 61, Nr. 6 (2023), 742-754.

[42] Nigel Bagnall, “Concepts of Land/Air Operations in the Central Region,” Part I, Rusi-Journal, 129 (1984, 3), 59-62.

[43] General Defense Plan 89, OPO 1/89 dated 14 August 1989, significant content presented by MG retired Mugo Melvin, during Exercise Francisca Ride, HQ GE/NL Corps Münster at 30 August 2021; Jeschonnek, “Die NORTHAG-Operationsplanung im Wandel der 1980er Jahre: Operatives Denken im Kalten Krieg,“ Österreichische Militärische Zeitschrift [ÖMZ] 61, Nr. 6 (2023), 742-754; Helmuth R. Hammerich, “Halten am VRV oder Verteidigung in der Tiefe? Die unterschiedliche Umsetzung der NATO-Operationsplanungen durch die Bündnispartner,“ in: Heiner Möllers/Rudolf J. Schlaffer, “Sonderfall Bundeswehr, Streitkräfte im nationalen und internationalen Vergleich,“ (De Gruyter, München 2014), 81-112.

[44] Helmuth R. Hammerich, “Halten am VRV oder Verteidigung in der Tiefe? Die unterschiedliche Umsetzung der NATO-Operationsplanungen durch die Bündnispartner,“ in: Heiner Möllers/Rudolf J. Schlaffer, “Sonderfall Bundeswehr, Streitkräfte im nationalen und internationalen Vergleich,“ (De Gruyter, München 2014), 92-93; 90-95; Thorsten Squarr, “Operative Beweglichkeit im Raum unter den Rahmenbedingungen der grenznahen Vorneverteidigung – ein Zielkonflikt,“ (Thesis at the German Defence College, Führungsakademie, Hamburg 1988); National Archives, DEFE 70/1276, [Period 1977-1982, subject BAOR, Forward Defence].

[45] Torsten Squarr, “Operative Beweglichkeit im Raum unter den Rahmenbedingungen der grenznahen Vorneverteidigung – ein Zielkonflikt,“ (Thesis at the German Defence College, Führungsakademie, Hamburg 1988).

[46] Helmuth R. Hammerich, “Halten am VRV oder Verteidigung in der Tiefe? Die unterschiedliche Umsetzung der NATO-Operationsplanungen durch die Bündnispartner,“ in: Heiner Möllers/Rudolf J. Schlaffer, “Sonderfall Bundeswehr, Streitkräfte im nationalen und internationalen Vergleich,“ (De Gruyter, München 2014), 91.

[47] German Archives BStU, [BA-BStU], MfS HV A 127, 179-181; BA-BStU, MfS HV A, 397, 51-56.

[48] Chief of the General Staff, “Design for Military Operations – The British Military Doctrine,” (Army Code 71451, London 1989), 47-50, Annex C, 75-84.

[49] National Archives [UK], DEFE 70/1276.

[50] Ibid; John Kiszley, “The meaning of manoeuvre,” Rusi-Journal, 142, Nr.6 (1998), 37.

[51] NATO-Military Agency for Standardization (NATO-MAS), Allied Tactical Publication 35 A, “Land Force Tactical Doctrine,” (ATP 35 A), (NATO, Brussels, 1978).

[52] Wesley Clark/Jüri Luik/Egon Ramms/Richard Shirreff, “Closing NATO’s Baltic Gap,” (International Center for Deterrence and Security, Tallinn 2016), 12.

[53] Markus Reisner, “Ukraine Krieg – Neue Phase, die Situation an der Front nach der zweiten russischen Winteroffensive,“ in: Truppendienst 63 (043/2204) Nr.399, 270-277.