Abstract: China’s weaponisation of economics is fully in line with China’s grand strategy. China relies mainly on using the indirect instead of the direct approach. Manoeuvre warfare as an indirect approach sees the opponent as an interconnected system, to which measures against identified vulnerabilities are applied. The goal is systemic destruction – the incapacitation or collapse of the opponent’s whole system – rather than cumulative destruction through a series of attritional engagements. An authoritarian government, like China, with unified, centralised and nearly unlimited state power exercise economic coercion through state capitalism against states, which rely on the private sector and an international, integrated global supply chain system for their economic welfare, using speed, agility and simultaneity.

Problem statement: Is the weaponisation of economics part of the competition with the People’s Republic of China?

So what?: We have to take the tools, features and endowments of coercive economic measures being applied by an authoritarian power towards liberal democracies to draw conclusions, what kind of deterrence and defence liberal democracies can muster to counter the threat.

Source: shutterstock.com/XC2000

The PRC’s Grand Strategy

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has a distinct understanding of what a Grand Strategy is and what kind of Grand Strategy the PRC defines as its own. The PRC has to be considered more and more a systemic rival.[1] It is therefore important not only to understand what fields are being considered as parts of the PRC’s Grand Strategy but also to understand the Strategic Culture of the PRC. The Strategic Culture is essential to be able to define what kind of approach the PRC is using in its current grey zone activities as the “awkward and uncomfortable space between traditional conceptions of war and peace”.[2] Those activities can be conducted in two ways, following the dichotomy of the direct or indirect approach,[3] respectively, the attritional or manoeuveral approach.[4] In the application of either the direct or indirect approach in economics, the specific features of authoritarian regimes versus liberal democracies and their respective economic models have to be considered. Finally, examples of how the weaponisation of economics is taken place and what potential avenues are to be explored as counterstrategies are provided.

The Strategic Culture is essential to be able to define what kind of approach the PRC is using in its current grey zone activities.

The PRC’s Grand Strategy and its implication for the use of economics

The definition of Grand Strategy in this paper is a broad and functional one; its role is to coordinate and direct all–disparate–resources of the nation (political, economic, technological and military) towards the attainment of a national objective.[5] In the PRC, it is understood as the “technique of national strategic management”.[6] It differs in two distinct ways from the more westernised definition: First of all, the instruments being used are not confined to the resources mentioned above, but include all the elements of comprehensive national strength.[7] This broader understanding got somehow lost in Western strategic thinking because it was already introduced very early through the term “political warfare”.[8] Secondly, the national objective of the PRC refers both to national security and national development, so it is applicable both in peace- and wartime and serves equally as an orientation for domestic and foreign affairs.[9] This distinction, especially the second, is important for further understanding the application of the Chinese Grand Strategy.

As the Grand Strategy serves to attain the national interest, it is important to be clear about the PRC’s core national interests – they are: “to maintain China’s fundamental system and state security; state sovereignty and territorial integrity; and the continued stable development of the economy and society”.[10] This leads to the conclusion, that “it is necessary to uphold a holistic view of national security, balance internal and external security, homeland and citizen security, traditional and nontraditional security, subsistence and development security, and China’s own security and the common security of the world.”[11]

One Major Determinant of the Grand Strategy

The foundation for the Grand Strategy is rooted in the Strategic Culture. The PRC considers Confucianism to be the determining factor in its own strategic thinking.[12] The Confucian concept of the da tong (typically called the “great harmony”) asks for harmony over conflict.[13] Considering the influence of Sun Tsu’s “Art of War”,[14] the Chinese self-perception is that it has always preferred defence over offence.[15] It is, therefore, stated in official documents as such.[16] The term “Cult of Defence“ was introduced to describe this cornerstone of self-perceived Chinese strategic thinking.[17] On the other hand, by analysing the wars the PRC was involved, the result looks much more contradictory to the self-perceived image: The PRC was quite willing to use force over time, influenced by realpolitik,[18] therefore it can be stated that “China’s leaders never seem to have seen a war they didn’t like.”[19] The term “offensive realism” is may be best suited for a summarising description.[20] The PRC’s military strategy, “Active Defence”,[21] can be seen as a combination of both understandings: “It can be proposed that the official thinking … fit into the ‘duality’ culture scheme…, with the strong, peaceful rhetoric and non-conflict preference, but increasingly assertive behaviour and pro-active stance when dealing with national (core) interests…”.[22]

The term “Cult of Defence“ was introduced to describe this cornerstone of self-perceived Chinese strategic thinking.

It will be necessary to clarify in what domains “Active Defence” is taking place. There is a rich pool of official and semi-official sources available for this. In the often-mentioned book “Unrestricted Warfare”, it is stated: “If we acknowledge that the new principles of war are no longer using armed force to compel the enemy to submit to one’s will”, but rather are “using all means, including armed force or non-armed force, military and non-military, and lethal and non-lethal means to compel the enemy to accept one’s interests.”[23] Although there are strong critics about the book as not being authoritative,[24] it was still published at the “PLA Literature and Arts Publishing House” and very likely with the consent of higher authorities – acknowledging the restrictions service members face when publishing work-related matters without permission. However, there are references to applying this kind of warfare in Chinese official documents.[25] As we focus on the domain of economics, it can be concluded: “The default behaviour and culture of the U.S. foreign policy community is to approach the economic domain mainly through the lens of competition, whereas the Chinese Communist Party’s organisational culture views the economic component of foreign policy through the lens of warfare.”[26]

The Indirect Approach as the Means of Choice

As the spheres of engagement are defined, it remains to outline how these engagements are being executed. The Strategic Culture is, as outlined, a main factor. Shortly after the publication of the aforementioned book “Unrestricted Warfare”, the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee and the Central Military Commission approved the concept of the “Three Warfares” in 2003.[27] It was integrated into the “Guidelines for the Political Work of the People’s Liberation Army”.[28] In an analysis of this concept, it was remarked:[29] “The “Three Warfares” is a concept that spans the war/peace divide, operating throughout the continuum of international rivalry. … there are few fixed patterns in Chinese strategy, and this is deliberate. How Beijing puts principles into practice will vary widely from circumstance to circumstance, confounding efforts at prediction. … the doctrine is entirely congruent with Chinese strategic culture, as well as with the universal logic of strategy.”[30] This concept also leads to the conclusion that “violence may be used as the final blow to knock out an enemy after it has been relentlessly sapped, subdues, and undermined from within.”[31] It also allows the interpretation that decisive manoeuvres can finish the conflict quickly to avoid a longer attritional engagement and limit the conflict’s size.[32]

Chinese Grand Strategy must, therefore, be understood as the national strategic management of all elements of comprehensive national strength. It determines both the foreign and domestic agenda, as the core national interests encompass international and national elements. The PRC will actively engage, if deemed necessary, in war and non-war-spheres if core national interests are being threatened. The PRC is already applying grey zone activities[33] and the weaponisation of economics prior to (sub-threshold) or part of a direct conflict is fully in line with the PRC’s Grand Strategy, as it is closely interlinked with the national development/well-being and hence with the survival of the communist party rule. In doing so, the PRC will refer to defensive offensives (and therefore preemptive strikes or self-defence counterattacks)[34] and will prefer the indirect over the attritional approach: “When it comes to ‘wars of choice’, though, the fact remains that the Chinese have traditionally favoured the indirect approach.”[35]

The Characteristics of an Indirect Approach Used by an Authoritarian Regime

To deepen the analysis of economic warfare through an indirect approach, a closer look at the fundamentals of the indirect approach is necessary:[36] The indirect approach views the opponent as an interconnected system to which measures against identified vulnerabilities are applied. The aim is to undermine the will and weaken the cohesion of the opponent’s system by defeating critical capabilities, as well as to set conditions and create opportunities to bring one’s own strengths to bear. It focuses on restricting options available to the opponent, preserving the maximum range of one’s own actions. It is subtler, and plausible deniability is easier to achieve. The core characteristics are a) speed, b) agility and c) simultaneity. These actions should ultimately lead to disruption, disorder (physical, functional, temporal and moral) and paralysis on the opponent’s side: The goal of manoeuvre warfare is systemic destruction–the incapacitation or collapse of the opponent’s whole eco-system (state, economy and society) – rather than cumulative destruction through a series of attritional engagements. This follows the logic of creating synergies: weakening one system in the interconnected ecosystem of the opponent will create a synergetic effect on the functioning of another system.[37]

In executing this strategy, the PRC, with its authoritarian regime and the application of state-capitalism, has advantages in speed, agility, and simultaneity over liberal democracies.[38] The decision-making is faster, as power in authoritarian states is centralised in the hands of a single leader or a small group of elites. There is no need for an extensive debate, public consultation, or legislative approval. The lack of opposition allows for a rapid implementation, as political manoeuvres, public protests, or legal challenges do not impede the implementation process. Authoritarian regimes can also swiftly adapt policies to changing circumstances due to a strong top-down control. They are not bound by lengthy legal processes, build-in checks and balances processes, or other procedures common to liberal democracies. The execution is more uniform and consistent across different regions and administrations, as the variability that might come from different regional/ local governments or political factions is severely reduced. The administrative machinery of the state is much more coordinated and synchronised, especially concerning large-scale projects and measures across various sectors/ areas of responsibility. Dissent and the following negotiations with various interest groups are not slowing down the implementation process. Lastly, direct control over (social) media allows for control over information dissemination and leads to steering public perception effectively so that all parts of society are much more aligned with state directives and opinions, as this would be the case in liberal democracies.

The PRC, with its authoritarian regime and the application of state-capitalism, has advantages in speed, agility, and simultaneity over liberal democracies.

The Indirect Approach and the Weaponisation of Economics

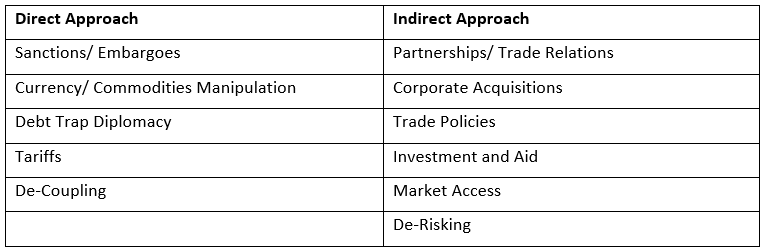

Several instruments for economic coercion can be identified, which can be clustered into means of the direct or indirect approach.

Source: Author.

Numerous examples could be found to outline the Chinese approach in each category, but only selected cases will be taken to illustrate the multipronged strategy of coercion. The first example is the “One Belt, One Road”- or “Belt and Road-Initiative” (BRI). It was initially designed to secure land routes to the Indian Ocean and integrate the Eurasian regions into a Chinese-led economic sphere. Today it encompasses several other initiatives under the roof of the BRI (for example, activities in Africa, South America and the Polar region, to name a few).[39] Since the beginning, a volume of 1.053 trillion USD of cumulated investment has taken place.[40] It consists mainly of a land belt and a maritime road to Europe. As the PRC is currently heavily dependent on several maritime chokepoints, both for their resources-import and their trade-exports, developing a land-based alternative was evident.[41] At the same time, new markets could be opened for its growing surplus production.

Looking at the maritime dimension, the PRC follows a so-called ’String of Pearls’ approach,[42] building a chain of seaports mirroring the Sea Lines of Communication from China to South Asia, South East Asia, the Middle East, parts of Africa and finally, Europe. Hungary may be the most prominent example of how the PRC is looking for opportunities to get a foothold into the community of European countries. As the first European country to sign a BRI agreement, Hungary has already received at least 16 billion Euro Foreign Direct Investment, making it the primary destination for Chinese business. In addition, Hungary has recently received a loan from the PRC of 1 billion Euros. On the other side, Hungary used between 2016 and 2022 six times its veto power to block the EU Council’s decisions against the PRC.[43] With the PRC partially mitigating the negative effect of Hungary’s strained relationship with the EU, Hungary is becoming the PRC’s bridgehead into Europe. Examples are the electric car manufacturing and battery production. But Hungary is also one of the main manufacturing and logistics hub for Chinese technology companies (e.g. Huawei). Looking at the current tariff conflict with the EU, such a bridgehead will help Chinese companies twofold. EU-imposed tariffs can be avoided more easily and the PRC can more easily continue to offload excess inventory to Europe and other countries to the extent of how domestic demand weakened. As a counter-measure to those tariffs, the PRC initiated an investigation into selected EU goods, such as pork (one of Spain’s biggest exports) and certain liquors (especially from France), in an effort to weaken European coherence. Another example would be Italy, which joined the BRI in 2019 but dropped out in 2023. In July 2024, however, a three-year action plan, including, for example, a cooperation agreement between Stellantis and Leapmotor on electric vehicles, was agreed upon. In summary, effects such as political capture through investment and aid policies as well as transforming a former nonexcludable and nonrival asset equally available to all commercial clients into a geopolitical token of the PRC of the BRI can be found.[44]

Hungary used between 2016 and 2022 six times its veto power to block the EU Council’s decisions against the PRC.

A second example is the use of trade/ export restrictions, especially with regard to critical materials, especially rare earths. In 2010, after an incident between the PRC and Japan,[45] the PRC imposed a two-month ban on exports of rare earths to Japan. In 2023, shortly after the restriction on semiconductor exports to the PRC, the PRC declared export restrictions on graphite products. This was followed immediately by another set of restrictions on germanium and gallium (both critical for the production of semiconductors). This happened after the Netherlands supported the U.S. restrictions (as the Dutch company ASML is the world leader in developing and manufacturing so-called photolithography machines necessary for the production of semiconductors. Recently, export restrictions were imposed on Antimony, without a clear incident as a trigger. It was only said that the export would be restricted in those cases where a country will use Chinese goods to undermine national sovereignty, security and interests. It has to be considered that it is not only so much the supply of the critical raw material itself, but the PRC has heavily invested in the refinery capacity as well. In graphite, for example, it refines more than 90 per cent of global supply.[46] It should also be considered that the PRC is trying to control the whole value chain in critical sectors: it controls up to 80 per cent of all production steps for solar panels and 60 per cent of those for wind turbines and electric car batteries alike.

As a last example, the strategy of de-risking[47] can be highlighted, where the characteristics of liberal democracies with independent, self-determined economic actors showcase the vulnerability in economic warfare. Looking at the example of the U.S., where the so-called “Outbound Investment Order” was a necessary addition to the existing export control rules. While selling critical technologies directly to the PRC was banned, investors were still allowed to fund Chinese firms developing the same technologies. Open markets with only lightly limited market actors (companies, investors and consumers alike) can only be steered to a certain extent in the direction of a specific national security interest. The same phenomenon can be observed in Germany. As de-risking was an agreed European strategy,[48] it was strongly advocated in Germany in 2023 as well.[49] In 2024, no structural and long-lasting effect can be observed.[50] In summary, it can be concluded that political statements do not equal corporate actions. On the other side, in the PRC, with its authoritarian structures, it is much easier to achieve, as the reaction towards Japan in 2012 – after another incident[51]–showed. After the state-controlled press made the incident public, it was for the government only to manage the popular aversion against Japan by channelling the nationalistic feelings of individuals and companies (expressed, for example, in the boycotts of Japanese goods, cancellation of flights and holidays, etc.) in the wanted direction.

The Necessity to Adapt

To conclude, the PRC aims to enhance and execute geopolitical and geoeconomic power globally, and at the same time, challenges/weakens the existing international rule-based order to install an alternative, accommodating to a greater extent Chinese values and political beliefs: “That order would span a ‘zone of super-ordinate influence’ in Asia as well as ‘partial hegemony’ in swaths of the developing world that might gradually expand to encompass the world’s industrialised centres.”[52] This order would follow the idea of a “community of shared future for mankind” (official English translation)[53] or a “community of common destiny for mankind” (a more literal translation).[54] This order would damage liberal and democratic values, as “order abroad is often a reflection of order at home”.[55] The prominent example of the failed attempt of “One Country, Two Systems” is a likely projection of the future order with the PRC as an at least partial hegemon. Economic coercion, especially applied through mainly an indirect approach as the PRC does, against states whose economies rely mainly on the private sector, an integrated global supply chain system for their welfare, and an open society regarding the spreading of information and media content, favors the authoritarian regime. Pluralistic welfare economies must adapt to maintain the escalation dominance–also in exchanges based on indirect approaches–against a monolithic party-state capitalism.

The prominent example of the failed attempt of “One Country, Two Systems” is a likely projection of the future order with the PRC as an at least partial hegemon.

There are several approaches of how an adaption could look like. Liberal democracies might create multilateral anti-economic coercion measures. This could be, for example, the set-up of new or the strengthening of existing bi-, tri- or multilateral agreements, which could create a more unified and cohesive barrier against coercion. Several examples can be found or are under discussion. ‘Quad’ (U.S., India, Australia, Japan) has gained momentum, in which the economic dimension (for example, supply chain resilience) is a strong pillar, and it is already reaching out to other organisations for common ground, in particular looking towards the EU and ASEAN.[56] Existing partnerships, like those between the U.S. and Japan or the U.S. and Korea, have been strengthened,[57] and new ones forged (U.S., Japan, Philippines).[58] Unilateral actions can also be observed, taking, for example, India’s Act East Policy[59] (also nicknamed Necklace of Diamonds) and – under the umbrella of the “India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor”[60] – its agreement with Iran to develop Chabahar Port[61] on the mouth of Hormuz Strait as counter-encirclement strategies to the PRC’s String of Pearls approach. There are other initiatives (e.g. the EU Global Gateway Initiative,[62] the multinational Supply Chain Resilience Initiative,[63] and the G-7’s Build Back Better World Initiative[64]) out there to convince countries to seek financial resources from multilateral rather than Chinese providers. Other former decisions are under scrutiny for renewal. One example would be the “Trans-Pacific Partnership”.[65] When the U.S. left, not only was a chance to lower trade barriers lost, but it also deprived the U.S.–with the help of like-minded partners – of co-designing the rules governing trade in the Asia-Pacific region. As a kind of replacement, the “Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement”[66] without U.S. participation, sees the PRC with its trading power in a central role. Active participation in supranational, international, and regional organisations not only has a (geo)economic but also a geopolitical dimension in terms of connectivity and influence with a strong economic multiplier effect. Efforts are underway to compensate for this situation, for example, the “Indo-Pacific Economic Framework”[67] with its 14 members has achieved progress in one pillar (supply chains), but another important pillar (trade) still lacks decisive advancement. The discussion is also to establish some form of the 1994 abolished “Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls”,[68] but now with a more expansive view of national security – not only looking at goods that can be used for military purposes as it was done before but integrating economic concerns to a greater degree. The term “economic NATO”[69] could fit the intended purpose.

Another potential thread to explore could be the creation of reverse dependencies, as the PRC still has an export-driven economic growth model. Although the PPRC is coming up to level playing fields in a lot of sectors and technologies, there are still areas where the Western world has market dominance. At the same time, the PRC’s national capacities and capabilities are not up to the cutting-edge level for still some time. Failing imports in those areas can make the PRC hardly a substitute. There will always be a domestic impact for the restricting countries, sometimes quite high, as it is the case with the U.S. ban on semiconductor exports to China (U.S. Federal Reserve estimates costs of 130 billion USD in collateral damage).[70] It has to be considered, though, that the PRC is not only implementing its own de-risking- and indigenisation strategy (in which, for example, “Made in China 2025” is part of it), but for the PRC, de-risking is not an economic goal; it is a political one, following a different logic from Western companies’ strategies.

There will always be a domestic impact for the restricting countries, sometimes quite high, as it is the case with the U.S. ban on semiconductor exports to China.

A last potential avenue to explore would be the creation of redundancies. Western liberal democracies and their economies depend on building as many trade relationships as possible, creating a possibility to hedge against unforeseen disruptions. That is true in the sense of infrastructure (as seen with the “Ever Given” in the Suez Canal and the necessity for rerouting due to the attacks of the Houthi in the Red Sea), but also for supply to meet demand. The model of frictionless, just-in-time supply chains with low inventories and stocks has to be scrutinised for geostrategic weaknesses. Such a strategy would be preemptive, both against inflationary shocks, abrupt decline in exports, and sudden decline in exports and other non-trade effects of geopolitics.

In the geopolitical and geoeconomic competition with the PRC, the indirect approach must be considered dead if it is unable to create a sufficient and balancing counter-effect to the PRC, which is using exactly the same kind of approach. Countering the indirect approach used by the PRC through direct means like sanctions (where the positive impact can be questioned anyway, seeing the sanctions against North Korea or lately Russia) or a full decoupling (with probably the same negative effect on GDP as it was the case due to the financial crisis or COVID-19), will probably deteriorate the fundamentals of our economic system. In addition, it remains questionable if the Western political systems and their societies at large would be able to survive this kind of competition.

Dr. Dipl.-Kfm. Wolfgang Müller; Research Interests: Total Defense, China, Weaponization of Economics. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of the German Institute for Defence and Strategic Studies. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of the German Institute for Defense and Strategic Studies or the German Armed Forces.

[1] N. Munro, “China’s identity through a historical lens,” in: K. M. Kartchner, et al., Routledge Handbook of Strategic Culture, London 2023, 179-192, 179; A. Small, “The meaning of systemic rivalry: Europe and China beyond the pandemic, European Council on Foreign Relations Policy Brief May 2020,” https://ecfr.eu/publication/the_meaning_of_systemic_rivalry_europe_and_china_beyond_the_pandemic/, October 12, 2024; R. Christie, “Rivals, not enemies,” in: International Politic Quarterly, September 2023, Rivals, Not Enemies | Internationale Politik Quarterly (ip-quarterly.com); C. S. Chivvis, “U.S.-China relations for the 2030s: Toward a realistic scenario for coexistence,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington. D.C. 2024, https://carnegie-production-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/static/files/Chivvis-US%20China%202030-final%201.pdf.

[2] N. P. Freier, C. R. Burnett, W. J. Cain jr., C. D. Compton, S. M. Hank, “Outplayed – Regaining strategic initiative in the Gray Zone,” https://press.armywarcollege.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1924&context=monographs, Xiii.

[3] Based on the work of Liddell Hart.

[4] Based on the work of John Fuller and John Boyd.

[5] Once again referring to the work of Liddell Hart.

[6] C. Wu, “Dialectics and the study of Grand Strategy: A Chinese view,” China Military Science, No. 3 2002, 144–145, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/CASI/Display/Article/2867621/itow-dialectics-and-the-study-of-grand-strategy-a-chinese-view/.

[7] The “Science of Military Strategy” says: “Strategic means take military power as the core, and also include comprehensive power including political, economic, diplomatic, scientific and technological, cultural, geographic and other related forces. It can be real power or potential power; it can be hard power or soft power. Its mode of action can be either a war action or a non-war military action; it can be through deterrence or actual combat.” (National Defense University: The Science of Military Strategy (revised 2020), https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/documents/Translations/2022-01-26%202020%20Science%20of%20Military%20Strategy.pdf, August 12, 2024, 17); see further: Ibid., 26.

[8] Political warfare was defined as “the employment of all the means at a nation’s command, short of war, to achieve its national objectives”. (G. F. Kennan, “The inauguration of organized political warfare,” April 1948, https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/102805/download); see also: W. R. Kintner, J. Z. Kornfeder, “The new frontier of war: Political Warfare, present and future,” London 1963.

[9] C. Wu , “Dialectics and the study of Grand Strategy: A Chinese view,” China Military Science, No. 3 2002, 145; the new economic philosophy with relevance to national security is called “dual circulation”, whereas the domestic circulation has a priority over the international circulation (see for example: A. Garcia- Herrero, “What is behind China’s Dual Circulation strategy,” in: China Leadership Monitor, No. 69 2021, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm/SSRN_ID3927117_code698134.pdf?abstractid=3927117&mirid=1), following the China Model or the Beijing Consensus (see: J. C. Ramo, “The Beijing Consensus,” The Foreign Policy Center Paper, March 2004, https://fpc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2006/09/244.pdf). This is fully in line with the “Made in China 2025” strategy. (see for example: J. Wübbeke, M. Meissner, M. J. Zenglein, J. Ives, B. Conrad, “Made in China 2025 – The making of a high-tech superpower and consequences for industrial countries,” Mercator Institute for China Studies Paper No. 2, December 2019, https://merics.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/Made%20in%20China%202025.pdf); see also: A. Wong, L.-E. Easley, H.-W. Tang, “Mobilizing patriotic consumers – China’s new strategy of economic coercion,” in: Journal of Strategic Studies, No. 6-7 2023, 1287-1324.

[10] B. Dai, “The core interests of the People’s Republic of China,” August 2009, https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2009/08/dai-bingguo-%E6%88%B4%E7%A7%89%E5%9B%BD-the-core-interests-of-the-prc/; see further extensively: National Defense University, “The Science of Military Strategy (revised 2020),” https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/documents/Translations/2022-01-26%202020%20Science%20of%20Military%20Strategy.pdf, 25); J. Zeng, Y. Xiao, S. Breslin, “Securing China’s core interests: The state of debate in China,” in: International Affairs, No. 2 2015, 245-266; Y. Chen, “Fully implement the overall national security outlook,” https://interpret.csis.org/translations/fully-implement-the-overall-national-security-outlook/.

[11] The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “China’s military strategy,” White Paper 2015, http://www.andrewerickson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/China-Defense-White-Paper_2015_English-Chinese_Annotated.pdf, 6.

[12] See in general on China’s Strategic Culture: A. Scobell, “China and Strategic Culture,” May 2002, https://press.armywarcollege.edu/monographs/822/; J. Li, “Traditional military thinking and the defense strategy of China,” 1997, https://press.armywarcollege.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1181&context=monographs.

[13] N. Lexiong, “Confucian thinking on war,” in: Cihai Xinzhi, No. 1 2000, 15-20; E. S. Boylan, “The Chinese cultural style of warfare,” in: Comparative Strategy, No. 4 1982, 341-366; Z. Chen, “The Chinese cultural root of the ‘Community of Common Destiny for All Mankind’ advances in social science,” in: Education and Humanities Research, No. 142 2017, 718-722; R. B. Geddis, “Ancient Chinese precedents in China’s national defense,” West Point 1987; S. Chan, “Chinese conflict calculus and behavior,” in: World Politics, No. 3 1978, 391-410.

[14] See for example: F. Ota, “Sun Tzu in contemporary Chinese strategy,” in: Joint Force Quarterly, No. 73 2014, 76-80; L. Zhuge, J. Liu, “Mastering the Art of War: Commentaries on the classic by Sun Tzu,” Boston 1989; E. O’Dowd, A. Waldron, “Sun Tzu for strategists,” in: Comparative Strategy, No. 1 1991, 25-36; A. Ghiselli, “Revising China’s Strategic Culture: Contemporary cherry-picking of ancient strategic thought,” in: The China Quarterly, No. 233 2018, 166-185; but it was not only Sun Tzu: “The traditional Chinese military writings, especially Sun Tzu’s Art of War, the Six Secret Teachings, Hundred Unorthodox Strategies, and Thirty-Six Strategems, have also enjoyed astonishing popularity…” (R. D. Sawyer, “Chinese strategic power: Myths, intent, and projection,” in: Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, No. 4 2006, https://jmss.org/article/view/57784, 8-9); see also: R. D. Sawyer, “The seven military classics of ancient China,” New York 1993.

[15] Based on the concept of “Chinas Peaceful Rise,” developed by Zheng Bijian (see on this: China’s peaceful rise: Speeches of Zheng Bijian 1997-2004, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/20050616bijianlunch.pdf); see for an analysis of the concept for example: B. S. Glaser, E. S. Medeiros, “The changing ecology of foreign policy-making in China: The ascension and demise of the theory of “Peaceful Rise”,” in: The China Quarterly, No. 190 2007, 291-310.

[16] The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “China’s national defense in the new era,” Chapter 2: “China’s defensive national defense policy in the new era,” Beijing 2019, http://www.andrewerickson.com/2019/07/full-text-of-defense-white-paper-chinas-national-defense-in-the-new-era-english-chinese-versions/, 7-13; the dominant notion of “defensive defense” can also be found in the other White Papers and in the “Science of Military Strategy” (see: National Defense University, “The Science of Military Strategy (revised 2020),” https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/documents/Translations/2022-01-26%202020%20Science%20of%20Military%20Strategy.pdf, 27).

[17] The term was introduced by Andrew Scobell (see: A. Scobell, “The Chinese Cult of Defense,” in: A. Scobell, “China’s use of military force: Beyond the Great Wall and the Long March,” New York, 2003, 15-39); see also: A. S. Whiting, “China’s use of force 1950-1996, and Taiwan,” in: International Security, No. 2 2001, 103-131; J. R. Adelman, C. Shih, “Symbolic war: The Chinese use of Force 1840-1980,” Taipei 1993; H. Feng, “A dragon on defense: Explaining China’s strategic culture,” in: J. L. Johnson, K. M. Kartchner, J. A. Larsen, “Strategic culture and weapons of mass destruction,” New York 2009, 171-187.

[18] M. Burles, A. N. Shulsky, “Patterns in China’s use of force: evidence from history and doctrinal writings,” Santa Monica 2000; A. I. Johnston, “Cultural realism: Grand Strategy in Chinese History,” Princeton 1995; J. K. Fairbank, F. A. Kierman, “Chinses ways in warfare,” Boston 1974; D. A. Graff, R. Higham, “A military history of China,” Boulder 2002; T. J. Christensen, “Chinese Realpolitik,” in: Foreign Affairs, No. 4 1997, 37-53; P. K. Singh, “Changing contexts of Chinese military strategy and doctrine,” New Delhi 2016.

[19] L. Burkitt, A. Scobell, L. M. Wortzel, “Introduction: The lesson learned by China’s soldiers,” in: L. Burkitt, A. Scobell, L. M. Wortzel, “The lessons of history: The Chinese People’s Liberation Army at 75,” Army War College Monographs No. 89 2003, 3-14, 7; see also: N. Godehardt, “The Chinese meaning of Just War and its impact on the foreign policy of the People’s Republic of China,” GIGA Working Papers, No. 88, 2008.

[20] A. J. Nathan, A. Scobell, “How China sees America -The sum of Beijings’s fears,” in: Foreign Affairs, No. 5, 2012, 32-47, 36.

[21] See for an example of elaborating on this concept: The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “China’s national defense,” 1998, http://www.andrewerickson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/China-Defense-White-Paper_1998_English-Chinese.pdf.

[22] R. Turcsanyi, “Strategic Culture in the current foreign policy thinking of the People’s Republic of China,” in: Czech Journal of Political Science, No. 1 2014, 60-75, 65-66; it was also stated, that China has a “pervasive acceptance of absolute flexibility – attacking or defending according to the opportunity provided by the ever-changing situation.” (Johnston 1995, 25)

[23] L. Qiao, X. Wang, “Unrestricted Warfare,” Beijing 1999, https://www.c4i.org/unrestricted.pdf, 7; further one it is also stated: “As the arena of war has expanded, encompassing the political, economic, diplomatic, cultural, and psychological spheres, in addition to the land, sea, air, space, and electronics spheres, the interactions among all factors have made it difficult for the military sphere to serve as the automatic dominant sphere in every war. War will be conducted in non-war spheres. If we want to have victory in future wars, we must be fully prepared intellectually for this scenario, that is, to be ready to carry out a war which, affecting all areas of life of the countries involved, may be conducted in a sphere not dominated by military actions.” (Ibid., 169).

[24]J. Baughmann, ‘Unrestricted Warfare’ is not China’s master plan, 2022, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/documents/Research/CASI%20Articles/2022-04-25%20Unrestricted%20Warfare%20is%20not%20China’s%20master%20plan.pdf.

[25] A White Paper on Defense, for example, states: “The PLA will upgrade and develop the strategic concept of people’s war, and work for close coordination between military struggle and political, economic, diplomatic, cultural and legal endeavours, uses strategies and tactics in a comprehensive way, and takes the initiative to prevent and defuse crises and deter conflicts and wars.” (The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “China’s national defense in 2006,” Beijing 2006, http://www.andrewerickson.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/China-Defense-White-Paper_2006_English-Chinese_Annotated.pdf, 9); in the resolution from the 20th Party Congress of the Chinese Communist Party at its Third Plenum, which traditionally focuses on economic policy, a whole section was dedicated to “Modernizing China’s National Security System and Capacity” (see: Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, “ China calls for new strategic guidance at 20th Party Congress,” October 2022, https://breakingdefense.com/2022/10/china-calls-for-new-strategic-guidance-at-20th-party-congress/.

[26] E. M. Seckler, T. Zahnow, “America’s reactive policy – How US organizational culture and behavior advantages China,” The Andrew W. Marshall Papers, July 2023, https://www.andrewwmarshallfoundation.org/library/americas-reactive-foreign-policy-how-u-s-organizational-culture-and-behavior-advantages-china/, 20; see also: Z. Z. Liu, Z.Z.: “Xi Jinping is preparing for economic war,” in: Foreign Policy, October 2022, 6-10; K. D. Johnson, “China’s strategic culture – A perspective for the US, Strategic Studies Institute Paper,” June 2009, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/101982/China_Strategic_Culture_June09.pdf, 8; V. D. Cha, “Collective resilience – Deterring China’s weaponization of economics interdependences,” in: International Security Nor. 1 2023, 91-124; E. A. Feigenbaum, “Is coercion the new normal in China’s economic statecraft?,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Paper, July 2017, https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2017/07/is-coercion-the-new-normal-in-chinas-economic-statecraft?lang=en; S. Halper, “China: The Three Warfares, Washington 2013,” https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/FOID/Reading%20Room/Litigation_Release/Litigation%20Release%20-%20China-%20The%20Three%20Warfares%20%20201305.pdf, 388-392.

[27] For a definition and description see: US Department of Defense, “Annual Report to Congress: Military and security developments involving the People’s Republic of China,” 2011, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2011_CMPR_Final.pdf, 26; see also: S. Halper, “China: The Three Warfares, Washington 2013,” https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/FOID/Reading%20Room/Litigation_Release/Litigation%20Release%20-%20China-%20The%20Three%20Warfares%20%20201305.pdf; E. Kania, “The PLA’s latest strategic thinking on the Three Warfares,” ChinaBrief, No. 13 2016; D. Livermore, “China’s Three Warfares in theory and practice in the South China Sea,” Georgetown Security Studies Review September 2020, https://georgetownsecuritystudiesreview.org/2018/03/25/chinas-three-warfares-in-theory-and-practice-in-the-south-china-sea/; M. Raska, “China and the Three Warfares,” The Diplomat, December 18, 2015, https://thediplomat.com/2015/12/hybrid-warfare-with-chinese-characteristics-2/; M. Clarke, “China’s application of the Three Warfares in the South China Sea and Xinjiang,” in: Orbis, No. 2 2019, 187-208.

[28] M. Stokes, R. Hsiao, “The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department – Political Warfare with Chinese characteristics,” October 2013, https://project2049.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/P2049_Stokes_Hsiao_PLA_General_Political_Department_Liaison_101413.pdf, 15; see also: People’s Daily, “PLA implements new political work regulation,” September 13, 2010, https://web.archive.org/web/20201002095352/http:/en.people.cn/90001/90776/7139024.html.

[29] J. R. Holmes, “Old – but strong – wine in new bottles – China’s “Three Warfares”,” in: S. Halper, “China: The Three Warfares,” Washington 2013, https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/FOID/Reading%20Room/Litigation_Release/Litigation%20Release%20-%20China-%20The%20Three%20Warfares%20%20201305.pdf, 247.

[30] The „Science of Military Strategy“ outlines: “’The Art of War’ is a strategic masterpiece full of strategic thoughts, which clearly advocates ‘scheming in the army’. Practice has proved that strategically superior strategies can often produce results that are difficult to achieve by pure material power, or become a “multiplier” of material power, allowing material power to exert extraordinary effects, and even achieve the goal of ‘winning war without fighting’.” (National Defense University, “The Science of Military Strategy (revised 2020),” https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/documents/Translations/2022-01-26%202020%20Science%20of%20Military%20Strategy.pdf, 23).

[31] M. Rolland, “Examining history to explore the future – France, the United States, and China 2050,” The Andrew W. Marshall Papers March 2023, https://www.andrewwmarshallfoundation.org/library/examining-history-to-explore-the-future/, 7.

[32] C. Bi, “On the soft casualty in modern wars,” in: Chinese Military Science, No. 5 2003, 122-126; Y. Yao, Z. Mao, “Sun Tzu’s Art of War and mainstream contemporary Chinese theories of war,” in: Chinese Military Science, No. 6 2004, 9-13.

[33] The definition of grey zone activities undertaken by China in this paper agrees with the following understanding: “Most definitions of the gray zone key on the uncertain political and operational space between war and peace; they describe calibrated coercion that does not breach certain escalatory thresholds while achieving certain coercive effects.” (I. B. Kardon, “Combating the Gray Zone: Examining Chinese threats to the maritime domain,” Testimony for the record before the House Committee on Homeland Security, Subcommittee on Transportation and Maritime Security, June 04, 2024, https://carnegie-production-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/static/files/2024.6.7%20Kardon%20CHS%20Testimony_rev.pdf.

[34] See in particular on the notion of ‘defensive offensives’: A. Scobell, “China and Strategic Culture,” May 2002, https://press.armywarcollege.edu/monographs/822/, 13.

[35] T. Corn, “Peaceful rise through Unrestricted Warfare: Grand Strategy with Chinese characteristics,” in: Small Wars Journal, June 2010, https://smallwarsjournal.com/blog/journal/docs-temp/449-corn.pdf, 16; see also: T. G. Mahnken, “Secrecy and stratagem: Understanding Chinese strategic culture,” Double Bay 2011, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/pubfiles/Mahnken,_Secrecy_and_stratagem_1.pdf, 24-26; J. Newmyer, “Oil, arms, and influence: The indirect strategy behind military modernization,” in: Orbis Spring 2009, 205-219.

[36] The following characteristics of an indirect approach were cumulated from several sources: L. Hart, “Strategy: The Indirect Approach,” New York 1954; E. N. Luttwark, “The operational level of war,” in: International Security, No. 3 1980/1981, 61-79; R. Fry, “The meaning of Manoeuvre,” RUSI Journal No. 6 1998, 41-44; J. Kiszely, “The meaning of manoeuvre,” in: RUSI Journal, No. 6 1998, 36-40; C. Tuck, “The future of Manoeuvre Warfare,” in: M. Weissmann, N. Nilsson, “Advanced Land Warfare,” Oxford 2023, 25-42; P. Garett, “Maneuver Warfare is not dead, but it must evolve,” in: Proceedings, November 2023, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2023/november/maneuver-warfare-not-dead-it-must-evolve; A. Neads, D. J. Galbreath, “Tactics and trade-offs – The evoluation of manoeuvre in the British Army,” in: M. Weissmann, N. Nilsson, “Advanced Land Warfare,” Oxford 2023, 321-351; W. J. Harkin, “Manoeuvre warfare in the 21st century,” August 2019, https://www.mca-marines.org/gazette/maneuver-warfare-in-the-21st-century/; R. Laird, “The manoeuvrist approach – Past, present, and future,” March 2019, https://sldinfo.com/2019/11/the-manoeuvrist-approach-past-present-and-future/; and also: S. Tzu, “The Art of War,” Oxford 1963

[37] In the “Science of Military Strategy it is said: “System confrontation is the inevitable future of war. … Contests between systems-of-systems with system-versus-system contests at its foundation will inevitably become a primary pillar of future combat.” (National Defense University, “The Science of Military Strategy (revised 2020),” https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/documents/Translations/2022-01-26%202020%20Science%20of%20Military%20Strategy.pdf, 268); also: “The principle of system is the most critical point in studying Grand Strategy (Wu, 2002, 148); references can also be found in western sources, for example: “Updating maneuver warfare to ‘system disruption warfare’ would better stress disrupting adversary systems across all domains.” (Garett 2023)

[38] The following arguments were summarized from the following sources: O. Mancur, “Dictatorship, democracy, and development,” in: The American Political Science Review, No. 3 1993, 567-576; A. Przeworski, M. E. Alvarez, J. A. Cheibub, F. Limongi, “Democracy and development – Political institutions and well-being in the world 1950-1990,” Cambridge 2012; D. Froomkin, I. Shapiro, “The new authoritarianism in Public Choice, New Haven 2019,” https://shapiro.macmillan.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/NAPC%2008-09-2019.pdf; M. McGuire, M. Olson, “The economics of autocracy and majority rule: The invisible hand and the use of force,” in: Journal of Economic Literature, No. 34 1996, 72-96; V. M. Hudson, C. S. Vore, “Foreign policy analysis – Yesterday, today, and tomorrow,” in: Mehrshon International Studies Review, No. 2 1995, 209-238.

[39] For a good – although accentuated – overview of activities in all the regions concerned, see: House Foreign Affairs Committee, “China regional snapshot,” https://foreignaffairs.house.gov/chinas-malign-global-influence-regional-snapshots/; see also: J. Smith, “China’s Belt and Road Initiative – Strategic implications and international opposition,” The Heritage Foundation Paper, August 2019, https://www.heritage.org/asia/report/chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-strategic-implications-and-international-opposition; for a Chinese view see: Center for Strategic and International Studies Interpret China, “The Belt and Road Initiative at 10 – Challenges and opportunities,” https://www.csis.org/events/belt-and-road-initiative-10-challenges-and-opportunities; for a regional view on the initiative see: Center for Strategic and International Studies Interpret China, “The Belt and Road Initiative at 10 – Regional perspectives on China’s evolving approach,” https://interpret.csis.org/the-belt-and-road-initiative-at-10-regional-perspectives-on-chinas-evolving-approach/.

[40] C. Nedopil, “China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report 2023,” Brisbane 2024, https://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0033/1910697/Nedopil-2024-China-Belt-Road-Initiative-Investment-report.pdf.

[41] See for the strategic importance of infrastructure: J. E. Hillman, “Influence and infrastructure – The strategic stakes of foreign projects,” CSIS Paper January 2019, https://www.csis.org/analysis/influence-and-infrastructure-strategic-stakes-foreign-projects.

[42] See for example: J. Ashraf, “String of Pearls and China’s emerging strategic culture,” in: Strategic Studies, Nor. 4 2017, 166-181; V. Bozhev, “The Chinese String of Pearls or how Beijing is conquering the sea,” in: De Re Militari October 2019, https://drmjournal.org/2019/08/26/the-chinese-string-of-pearls-or-how-beijing-is-conquering-the-sea/, 22-31; M. Dabas, “Here is all you should know about String of Pearls, China’s policy to encircle India,” in: India Times, June 23, 2017, https://www.indiatimes.com/news/india/here-is-all-you-should-know-about-string-of-pearls-china-s-policy-to-encircle-india-324315.html.

[43] European Parliament, “The implementation of Article 31 of the Treaty on European Union and the use of Qualified Majority Voting – Towards a more effective Common Foreign and Security Policy?,” Brussels 2022, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2022/739139/IPOL_STU(2022)739139_EN.pdf, 64.

[44] For an analysis of the trade and debt implications, see: World Bank Group, “Belt and Road economics,” Washington 2019, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/715511560787699851/pdf/Main-Report.pdf.

[45] See extensively: NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, “Hybrid Threats – The 2010 Senkaku crisis,” https://stratcomcoe.org/cuploads/pfiles/senkaku_crisis.pdf.

[46] For an overview of Europe‘s dependence on China in critical materials, see: European Commission, “Study on the critical raw materials for the EU 2023 – Final Report,” Brussels 2023, 47-53.

[47] De-risking is understood as diversifying from excessive dependence on strategic goods/components, and it is distinctively different from de-coupling.

[48] See for an overview: European Parliament, “European economic security – Current practices and future developments,” In-depth Analysis, Brussels 2024; MERICS, “Europe-China-360°,” December 2023, https://merics.org/sites/default/files/2023-12/MERICS%20Europe-China%20360_14%20December%202023.pdf, 12.

[49] Auswärtiges Amt, „China Strategie der Bundesregierung,“ https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/blob/2608578/810fdade376b1467f20bdb697b2acd58/china-strategie-data.pdf, 34-39.

[50] O. Spillner, G. Wolff, „China de-risking – A long way from political statements to corporate action,“ DGAP Policy Brief No. 16 2023, https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/87681; J. Matthes, “Importseitiges De-Risking von China im Jahr 2023 – Eine Anatomie hoher deutscher Importabhängigkeiten von China,“ IW-Report No. 18 2024, https://www.iwkoeln.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Studien/Report/PDF/2024/IW-Report_2024-Importabh%C3%A4ngigkeiten-China.pdf.

[51] M. T. Fravel, “Explaining China’s Escalation over the Senkaku (Diaoyu) Islands,” in: Global Summitry, No. 1 2016, 24-37.

[52] R. Doshi, “The long game – China’s Grand Strategy to displace American order,” August 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-long-game-chinas-grand-strategy-to-displace-american-order/; see also for Asian states favouring a logic of hierarchy: D. C. Kang, “Hierarchy, balancing and empirical puzzles in Asian international relations,” in: International Security, No. 3 2003/ 2004, 165-180.

[53] The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, “The Belt and Road Initiative: A key pillar of the Global Community of Shared Future,” October 2023, https://english.www.gov.cn/atts/stream/files/6524b3d7c6d0c788098ffefc.

[54] L. Tobin, “Xi’s vision for transforming global governance: A strategic challenge for Washington and its allies,” in: The Strategist, No. 1 2018, 154–166; D. Zhang, “The concept of ‘Community of Common Destiny’ in China’s diplomacy: Meaning, motives and implications,” in: Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, No. 2, 2018, 196–207; Z. Chen, “The Chinese cultural root of the ‘Community of Common Destiny for All Mankind’ advances in social science,” in: Education and Humanities Research, No. 142 2017, 718-722; and more recently: T. R. Heath, “Xi’s cautious inching towards the China dream,” August 2023, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/xi-s-cautious-inching-towards-the-china-dream.

[55] C. Edel, D. O. Shullman, “How China exports authoritarianism,” in: Foreign Affairs Snapshot, September 16, 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2021-09-16/how-china-exports-authoritarianism.

[56] S. K. Kalyani, “Economic relevance of Quad as a regional strategic forum,” July 2022, https://www.thepeninsula.org.in/2022/07/25/economic-relevance-of-quad-as-a-regional-strategic-forum/.

[57] U.S. Department of Defense, “Japan, South Korea, U.S. strengthen trilateral cooperation,” https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3498451/; C. Wooseon, “New horizons in Korea-U.S.-Japan trilateral cooperation,” https://www.csis.org/analysis/new-horizons-korea-us-japan-trilateral-cooperation.

[58] U.S. Department of Defense, “The U.S., the Philippines, and Japan launch the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment Luzon Economic Corridor,” https://www.state.gov/the-united-states-the-philippines-and-japan-launch-the-partnership-for-global-infrastructure-and-investment-luzon-economic-corridor/; E. L. Murphy, G. B. Poling, “A new trilateral chapter for the U.S., Japan and the Philippines,” https://www.csis.org/analysis/new-trilateral-chapter-united-states-japan-and-philippines.

[59] A. Sharma, P. Basu, “Ten years of India’s Act East Policy,” https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/ten-years-of-india-s-act-east-policy; S. Sarish, “India’s neighborhood policy towards the Southeast Asian region: A study on Act East Policy,” 2022, https://india.hss.de/download/publications/A_Study_on_Act_East_Policy.pdf.

[60] A. Rizzi, “The infinite connection: How to make the India-Middle East-Europe economic corridor happen,” April 2024, https://ecfr.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/The-infinite-connection-How-to-make-the-India-Middle-East-Europe-economic-corridor-happen.pdf.

[61] M. Salami, “Despite a recent India-Iran agreement, challenges loom for Chabahar Port for India,” July 2024, https://www.stimson.org/2024/despite-a-recent-india-iran-agreement-challenges-loom-for-chabahar-port/.

[62] European Commission, “Global Gateway,” https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/global-gateway_en.

[63] World Economic Forum, “Global supply resilience initiative,” https://initiatives.weforum.org/global-supply-resilience-initiative/home.

[64] C. M. Savoy, S. McKeown, “Opportunities for increased multilateral engagement with B3W,” https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/220506_Savoy_Multilateral_Engagement_B3W.pdf?VersionId=sGCXUbdA9NUst4TuA08r8dutmJ7rB2w7.

[65] J. McBride, A. Chatzky, A. Siripurapu, “What’s next for the Trans-Pacific-Partnership?,” https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-trans-pacific-partnership-tpp.

[66] U.S. Congressional Research Service, “Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement,” October 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11891; Asian Development Bank, “The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement: A new paradigm in Asian Regional Cooperation?,” May 2022, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/792516/rcep-agreement-new-paradigm-asian-cooperation.pdf.

[67] I. Manak, “Unpacking the IPEF: Biden’s Indo-Pacific trade play,” November 2023, https://www.cfr.org/article/unpacking-ipef-bidens-indo-pacific-trade-play; R. Ward, “The political significance of the new Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity,” May 2022, https://www.iiss.org/sv/online-analysis/online-analysis/2022/05/the-political-significance-of-the-new-indo-pacific-economic-framework-for-prosperity/.

[68] J. H. Henshaw, “The origins of CoCom: Lessons for contemporary proliferation control regimes,” The Henry L. Stimpson Center Analysis, Report No. 7, May 1993; see for an analysis: U.S. Congressional Research Service, “Export controls – International coordination,” September 2023, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47684.

[69] See for example: D. Alperovitch, “Democracy needs an economic NATO: Fighting Chinese coercion requires new alliances,” May 2024, https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/05/23/democracy-economic-nato-china-coercion-taiwan/.

[70] K. Gupta, C. Borges, A. L. Palazzi, “Collateral damage: The domestic impact of U.S. semiconductor export controls,” July 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/collateral-damage-domestic-impact-us-semiconductor-export-controls.