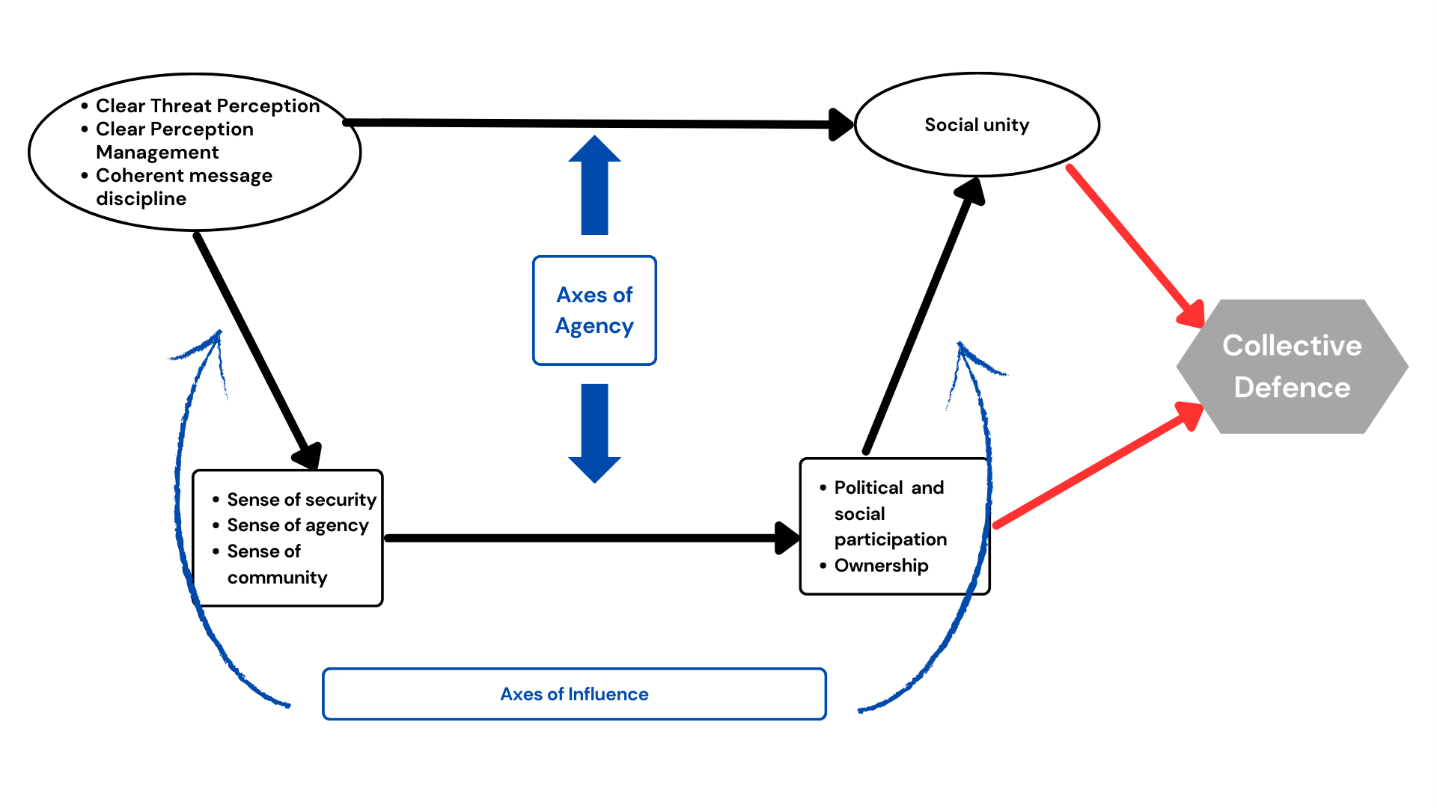

Abstract: Collective security in democracies is unviable without public trust and a publicly cogent threat assessment. Thus, it follows that democratic security architects should promote an internally-focused threat perception and engage in realistic perception management. There needs to be a greater focus on what we have that is worth protecting, and why; moreover, threat perceptions should focus on what the democracies can do, rather than the inverse perception of what harm a threat can inflict, as such threat perceptions promote enfeeblement. This paper argues that an internally-focused threat perception, reinforced through a ‘seductive’ model of message discipline, will foster social cohesion and consequently collective defence.

Problem statement: How to understand the democratic race to the bottom, where elections are won by the least unpopular rather than the most popular, weakening social cohesion and collective defence?

So what?: Security policymakers and their polities need to consciously see, set, and say what the problems are if they wish to address them. Furthermore, in democracies, security problems must be considered in the context of the lives of the people. Simply put, if the population cannot see or understand a threat, and if it is not communicated coherently, then there is no reason to believe that the people will accept it, let alone act on it. In such instances, the foundations of any collective defence may be undermined.

Source: shutterstock.com/Wojciech Wrzesien

Community Cohesion?

Following the Russian state’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, NATO has bounced back to life, throwing itself into the here and now. Likewise, the EU is taking unprecedented—albeit seemingly inadequate—steps to help the Ukrainian people defend themselves.[1] Yet, amongst the public in European and alliance states, there is a vast plurality of positions ranging from the seemingly cowed, through blithe indifference, to semi-active belligerence. What there is not is community cohesion.

In a democracy, political consideration and inclusion of the populace are crucial. As security and defence issues are often elite-led, they may—as in the case of British participation in the invasion of Iraq—not be viewed in the people’s interest.[2] As Olga Onuch notes, democracy at the human level is a pull factor for states outside the EU and NATO.[3] It is thus logical that failure to obtain broad democratic support in defence and security matters or to protect the address the interests of the populace may lead to discontent or delegitimisation.[4]

Consequently, the problems of forming collective defence in a democracy lie in threat perception, perception management, and message discipline: in other words—in the mind of the people. To a degree, these relate to two of four principles laid out in the Swedish Psychological Defence Agency’s report Psychological Defence: Concepts and Principles for the 2020s, particularly ‘threat intelligence’ and ‘strategic communications’.[5] This perspective sets collective defence as a human-focused phenomenon, which, in a democracy, it must be. Reflecting on the choice of human-as-referent, Bill McSweeney views the human individual as primary, as they are ultimately ‘the bearers of security and insecurity’.[6] Furthermore, in democracies, the populace, in theory, has a say on how things are or ought to be. Consequently, the individual must have a seat—conceptually, if not literally—at the collective defence table. This perspective is particularly important, as Ken Booth notes, “the daily threat to the lives and well-being of most people and most nations is different from that suggested by the traditional military perspective”.[7] This it is incumbent upon democratic states to ensure that there is accord between these aspects; naturally, the reverse is also true—citizens should also be well informed on such matters, and the democratic states should recognise this and facilitate it.

The problems of forming collective defence in a democracy lie in threat perception, perception management, and message discipline.

Idealised view of micro-foundations of social polarisation today—modified ‘Coleman Boat’ by author.

In trying to understand the macro-micro relations in social theory, James Coleman noted that in the early 20th century, sociologists were turning away from theories of action, just as industry and manufacture were creating national communities and collectives.[8] This creation was achieved through the development of media such as radio and magazines, which led to the creation of a need to understand consumer- and, consequently, social behaviour. Reflecting, if not reversing Coleman’s observation, today, there is political polarisation; instead of firm foundations, there are cracking collectives. This polarisation is attributable to a range of causes: inequality stemming from the austerity of the 2008 financial crises, the impacts of the COVID pandemic, and FIMI (Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference) conducted through what we might call ‘industrial scale’ manipulation and targeting on social media. Together, these have helped in the atomisation of democratic society. Reflecting this is the diffusion of coalition and minority governments in many European states.[9] This latter point is vital, for it testifies to a lack of collective and, more broadly speaking, a lack of nucleus around which a collective might form.

Threat Perception

Threat perception pertains to understanding the competitive nature of the international environment: actions and goals may be contested. More particularly, as Janice Gross Stein notes, “threats do not unambiguously speak for themselves. Understanding the meaning of threats is mediated by the perception of the target”.[10] Consequently, this definition infers a level of agency on the target state—the threat is there to be taken. However, states and alliances must see and understand threats and, most crucially, ensure that steps are taken to mitigate threats. In Europe, the lack of a cohesive threat perception has left most countries unprepared for a range of socio-security challenges, from energy independence to the ability to conduct large-scale combat operations (LSCOs)—and these may even be interlinked.

Threat perception pertains to understanding the competitive nature of the international environment: actions and goals may be contested.

The paltry state of security in Europe suggests that policymakers and planners have largely failed to perceive, never mind address, threats adequately. Worse still, there has been a failure to sensitise the European public to the high-end threats they face. The term “high-end” distinguishes them from threats that are a nuisance but otherwise manageable, such as terrorism and crime. Threats may be considered “low-end” when they do not represent existential threats in the way that state intransigence from Russia or China might. It is not intended to say that transnational terror groups like ISIS do not pose substantial threats to Europe, but rather that such threats are—as has been demonstrated—neither existential nor unmanageable.

In sheer material terms—financial, military, industrial, human—the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is the largest threat to Europe, but by briefly adopting Mearsheimer’s concept of ‘the stopping power of water’, the PRC, by virtue of distance, is an indirect threat.[11] Russia, by contrast, by shared neighbourhood, and by actions, is not.

Post-Soviet Russia’s willingness to ignore international rules has been clearly on display since FSB agents murdered Alexander Litvinenko in London in 2006. Furthermore, Russia’s open hostility to Europe has been visible since as far back as 2007, when Russian President Vladimir Putin accused NATO of ‘putting military infrastructure’ on Russia’s borders and accused the collective West of “imposing” walls and divisions on the world.[12]

Since Putin’s assertions, Russia has cyber-attacked Estonia, invaded Georgia, indiscriminately bombed Syria, seized Crimea, launched a war in Donbas, shot down a civilian airliner full of Europeans, blew up a Czech arms depot, and ultimately invaded Ukraine. It has also interfered in U.S. elections and used chemical weapons in the UK, not to mention murdering dissenters at home and in a multitude of European countries. Yet, when in 2012, U.S. presidential candidate Mitt Romney declared that Russia was the U.S.’s biggest geopolitical foe, Barack Obama mocked him for this statement, wittily remarking that the 1980s had called to say they wanted their foreign policy back.[13] Similarly, when in 2019, French President Emmanuel Macron decried the ‘brain death’ of NATO, he was also mocked. Both instances stand in testament to a strategic irreality that has allowed threats to Europe to fester.

European policymakers have had, at a minimum, 17 years to course-correct European security away from vulnerabilities related to Russia or, more particularly—the regime. However, for a myriad of reasons, this did not happen, or at least not to a degree adequate to ensure the Russian regime did not act outside the norms of international society. Consequently, it is arguable that today, both Europe’s energy dependence on Russia and a diminished defence industrial and technical base are the symptoms of inadequate threat perception.

European policymakers have had, at a minimum, 17 years to course-correct European security away from vulnerabilities related to Russia or, more particularly—the regime.

One of the foundational problems with threat perception is that what you see depends on where you sit. Early in the Cold War, Europe (Western Europe, that is) faced three fundamental threats: financial ruin, Soviet subjugation, and German revanchism. These were encapsulated in the formulation supposedly uttered by NATO’s first Secretary General Lord Ismay, that the purpose of NATO was “to keep the Soviet Union out, the Americans in, and the Germans down”.[14] Had he lived long enough, Ismay may well have looked proudly on Europe in 1989 when the Soviet Union finally began to unravel. However, he would certainly have looked on in dismay at the unravelling of Europe in 2019, when Macron rightly cast his aspersions on NATO, and many European states were riven by Russian attempts to destabilise the continent. Today, it seems that Europe has gone from Ismay to dismay.

Across Europe, different states naturally have varying perspectives on a multitude of issues; defence is no different. Some states are acutely aware that peer competition has returned. Sweden is an example of this. Since 2015, Sweden has ramped up its Totalförsvaret (Total Defence) concept. Totalförsvaret is not merely a rearmament plan but a whole-of-society—both civil and military—plan to ensure state survival.[15] Yet, whilst Sweden is preparing its people for the return to conventional war to Europe, others, such as the UK, continue to draw down conventional forces or, as in the case of certain neutral states, continue to conduct business as usual.

Part of the explanation of misaligned threat perception can be found in distance. For example, Wolfgang Wagner notes in his study of Europe’s Radical Left and its disposition towards Ukraine, there is a correlation between distance from and assertiveness towards Russia.[16] Beyond left-right ideology, there is a spatial trend in defence spending amongst European NATO members in 2024. Data shows that spending largely trends upward the closer one gets to Russia, with Poland, Estonia, and Latvia all breaking 3% of GDP on defence. In contrast, Spain, Portugal, and Canada all lag below the 2% guideline.[17]

Data shows that spending largely trends upward the closer one gets to Russia, with Poland, Estonia, and Latvia all breaking 3% of GDP on defence.

This variation in spending indicates strongly—though not wholly—that certain states in Europe are alive to the threat in the east. However, the same data set also shows that the picture was less clear-cut in 2015.[18]

Perception Management

In contrast to threat perception, perception management acknowledges a threat. It relates to having the audience understand the spectrum of a threat(s) and where each item sits. Perception management must be done reasonably but accurately, lest it be self-fulfilling; it must discuss the threat’s capacities and one’s ability to mitigate it. As Schumpeter noted prophetically, “if organisations are created which gain status and reward from threats, those organisations will seek out and dramatise threats” [emphasis added].[19] More recently, Janice Gross Stein reiterated this concern, noting that “organisational and bureaucratic politics can produce pathologies where leaders structure problems in ways that increase their importance and push hard for solutions that advance their institutional interests”.[20] Consequently, perception management must not be like the Tinman, the Lion, and the Scarecrow in The Wizard of Oz, who accept myth as fact, and are thus cowed into acquiescence. European threat assessment needs to be more Dorothy, to possess clarity to see things for what they are, be willing to change, and have the courage to stand up for what is right.

Practically speaking, a failure of perception management may serve to underestimate the opponent. For example, one need only look at Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; Russian planners thought—despite the fact Russia had been fighting Ukraine for 10 years—that Ukraine would cut and run in the face of Russian might. Moreover, Ukraine, despite, rather than because of, the paucity of Western support, reversed many of Russia’s early gains.

Conversely, poor perception management might lead one to overestimate an opponent. For many years, Russia has been viewed as a supremely powerful state because it fits realist notions of power: a large military, a ‘strong’ economy, a strong head of state, and so on. Consequently, it has been accorded significant diplomatic accommodation. Yet, respect for Russia goes beyond what should be considered reasonable.

The Russian military has been much vaunted, with “successes” in Syria and Crimea (although curiously, not Donbas) being touted as a testament to its excellence in operational art and military modernisation. Yet, in both instances, Russia was the beneficiary of something of a reverse-Maoism. That is to say, normally, in an insurgency, it is the insurgent, not the state, who needs access to a safe harbour. In capturing Crimea, Russia was aided by the absence of a weak state and the deep presence of Russian forces already in-situ and among a friendly population. In Syria, Russia was protected by a corrupt, despotic regime which provided access to facilities to conduct an unopposed air campaign against civilians.[21] In neither case was Russian success the product of skill-at-arms or a genuine test of might. Rather, Russia exploited internal turmoil within weak states as a means to project an image of strength, and many states bought it.

The Russian military has been much vaunted, with “successes” in Syria and Crimea being touted as a testament to its excellence in operational art and military modernisation.

Where Russia has been successful is in parlaying its perceived strength into fear in Western policy circles, observable in US and German prevarications to arm Ukraine adequately. These prevarications are borne out of fears of escalation. These fears fly in the face of observed actions; several Moscow watchers have noted that Putin and his regime frequently stand down when confronted with force or with decisions that will paint him unfavourable.[22] Yet, Germany steadfastly refuses to release the Taurus Cruise Missile—although the ground may be moving on this under Chancellor Merz—, and the US has reluctantly allowed Ukraine to conduct limited long-range precision strikes on Russia with US-supplied weapons. These actions are illustrative of many examples which have allowed Russia to inflict terrible damage on Ukrainian forces and civilians. In the long run, these may lead to Russian battlefield success that serves to self-actualise Western fears about Russian strengths. In the event of such a Russian success, misperception may reinforce the idea that Russia can overcome a country of 40 million armed with Western equipment—when the reality is that Russia is struggling to overcome its smaller neighbour who was given tools to fight, not tools to win.

Whilst the courageous restraint of Western policymakers can be applauded, it may be misguided and likely incredibly short-sighted. Russia is, without a doubt, the greatest threat to security in Europe for the past 35 years. Yet, at the same time, it is not uncharitable to say that, like the Assad regime, the Russian state is a built house on sand.

Russia is a sclerotic state with an economy only four times larger than Austria—for a population 15 times larger.[23] It possesses an army worn threadbare by twenty-five years of corruption, compounded by three years of Ukrainian resistance. It is a petro-state vulnerable to the vagaries of price fluctuation. It possesses an ageing population beset by poor living standards, poor health, and poor prospects; it is also riven by criminal factions and ethnic cleavages—this is only a recipe for domination if accepted by its victims.

Whilst it would be remiss in failing to acknowledge that Russia is a “nuclear power”, this is so only in the sense that Russia possesses nuclear weapons. Nuclear power does not translate to usable power.[24] As Ken Booth notes, in discussing important words “such as ‘war’, ‘strategy’ and ‘weapon’’, they each ring Clausewitzian bells of reasonable instrumentality, but when the adjective ‘nuclear’ is put in front of them, as it often is, Clausewitz marches out of the window”[emphasis added].[25] The same must apply to states.

Nuclear power does not translate to usable power.

Russia is not alone among nuclear weapons states to be on the end of military malaise. The US has lost three wars since becoming a nuclear-powered state; Vietnam beat China back across; and Britain was undermined by 30 years of low-intensity conflict in Northern Ireland, all whilst giving the pretence to be a world power. And this is without mentioning the recent fighting between India and Pakistan. That is not to say that nuclear weapons should be ignored; it seems, however, that, unless the Russian regime is also a millenarian death cult—which it is not—being a nuclear power is unlikely to matter in any concrete sense. This point is reinforced by the fact that Russian nuclear messaging is often directed at internal consumption through the narrative espousal of what seems like incredible wonder weapons such as Sarmat and Burevestnik. This internal messaging serves to bolster the regime by displaying perceived might. However, we must bear in mind that in the most real sense, we should consider wonder weapons from the perspective that they should make any serious analyst wonder whether the weapon’s creators or its promoters actually believe the ludicrous claims they make. Furthermore, fear of the irrationality of the Russian regime’s fatalism is undermined by the fact that the regime has taken great pains to ensure its survival both in the personage of the president and—as often overlooked—in the bureaucratic machine that enables it.[26]

Russia has the combat power, national will, and economic endurance to conquer Finland, Estonia, or Romania, but likely only in a 1v1 setting. Collectively, the West, be it the EU27 or NATO, possesses the means both economically and militarily to end Russian intransigence; this is something policymakers need to internalise in themselves and in their populations.

Message Discipline

Message discipline is the practice of systematically promoting a consistent message. This must have a clear audience and be internally coherent to be effective. It must be something the audience can also internalise and make their own.

A seemingly excellent example of message discipline comes from Donald Trump: Make America Great Again (MAGA). This pithy slogan embodies a desire to return to a—non-existent—time when things were better. The beauty of this slogan is that it is almost a Rorschach test for the adherent; it can mean whatever the adherent wants it to mean, because, ultimately, it is aspirational rather than deliverable. Likewise, another example of poor message discipline is the multitude of voices on how Ukraine should conduct its war to liberate itself from Russian aggression. There should be one message and one voice, and in the case of war in Ukraine, that voice should be Ukrainian. Alas, it is not.

Another example of poor message discipline is the multitude of voices on how Ukraine should conduct its war to liberate itself from Russian aggression.

To be strategic, Sguazini and Mazziotti di Celso argue that the message must be important and deliberate. They state that such communications “are ’strategic’ not only because they are about matters of great importance but also because they do not arise spontaneously, and so are the products of deliberation. For a narrative to have the desired effect, it must relate in some way to the experience, culture and concerns of its intended audience”.[27] Furthermore, message repetition is de rigueur, if one wishes to promote recall; as Jonah Berger puts it: “top of mind is tip of tongue”.[28] As Grahn and Pamment note, “repeated exposure to a claim, even if it is false, can make it seem more credible over time”[emphasis added].[29] Thus, it becomes simple to see why message discipline is vital.

European messaging on Ukraine has often been muddled because of shifting internal political dynamics, battlefield change, and in some states because of illiberal heads of state. Furthermore, messaging has been somewhat clunky and opaque. Announcements that Europe stands with Ukraine do not reflect realities such as the European state’s inconsistent provision of material means. In addition, as Garvan Walshe notes, the proclamation to stand with Ukraine ‘for as long as it takes’ is fuzzy in that it lacks a purpose.[30] In this construct, the audience is forced to ask, “as long as what takes”—what is the purpose of standing with Ukraine? Walshe addresses this with a suggested change in message: Europe should not support Ukraine for as long as it takes—but rather to assure Ukraine’s victory as soon as possible.[31] In this construct, the purpose is clear; it is, to a more concrete degree, deliverable—Russia can be beaten.

Europe should not support Ukraine for as long as it takes—but rather to assure Ukraine’s victory as soon as possible.

In crafting messages on collective defence, it is not necessary to act as if Europe—or the West—needs an orientating enemy. Such practice is old wine in new bottles and will not lead to progress.[32] Repeating the mistakes of the past defeats the point of studying history and politics.

Rather than viewing Russia as an enemy, the focus should be placed on threats emanating from the regime. Painting Russia as the enemy has two significant flaws: 1) it ‘others’ ordinary Russians who have no truck with the regime but who are, at the same time, trying to eke out an existence in a repressive political regime. As largely human-focused democracies, European states should seek to attract and protect the individual. 2) An enemy-focused perspective denies agency—remove the threat, and you remove a unifying political force; what’s more, as history shows time and again, insecurity persists, even after an enemy is vanquished, thus an external threat/enemy-focussed perspective is essentially short-termist.

Consequently, messaging should be primarily self-referential and inward-looking. European messaging should convey not what the threat wants, intends, or aims but what is worth protecting. This perspective has a second, somewhat easy-to-overlook attribute that is beneficial: it is inherently defensive. And thus, not competitive with heavy costs to external actors. Positive, self-referential messaging should be simple for Europeans, after all, we live—relatively speaking—in what we might call a lustrous leviathan composed of 400 million people bequeathed with some of the greatest living standards and the highest levels of human freedom in recorded history. With appropriate, positive message discipline, policymakers can evoke a suitably seductive rationale for building collectives and collective defence.

The Rural-Urban Divide

The idea of a rural-urban divide has a long pedigree; however, it is only necessary to consider the ramifications of the divide on this side of 2008. This is because the current malaise largely stems from the fallout of the financial crash, since which the EU has been in a state of ‘permacrisis’ and from which both the PRC and Russia have gained ascendancy of sorts.[33]

Across the political literature, it is accepted that there is something of a bifurcation in European politics (and those of the U.S.) between urban and rural communities. This is visible in the vast literature on the topic and the existence of research projects such as the Rural-Urban Divide in Europe (RUDE).[34] In broad strokes, this divide manifests in anti-system resentment that seems more prevalent in rural, semi-rural, and small-town populations than in larger cities.[35] However, some, like Nathalia Vigna, believe that this is a core-periphery issue rather than a strictly rural-urban one.[36] Regardless, whatever the actual loci of discontent, the consequence of anti-system politics in the Western body politic is the growth and sustenance of parties with anti-system/anti-globalist agendas.

Across the political literature, it is accepted that there is something of a bifurcation in European politics between urban and rural communities.

Thus, the divide and its anti-system politics are a cause for concern: They erode social cohesion, which undermines the collective and may impact collective defence. They diminish democratic norms and traditions, as seen in the rise of autocratic and illiberal leaders in the U.S., Hungary, Slovakia, and Türkiye. Finally, they are a vector for exploitation by external actors. This is visible in the profusion of Russian money in extremist parties across Europe (both Left and Right) and the US.

To address the first point, one has to understand the so-called “places left behind”. Marie Hyland notes that many people feel that they lack recognition in such places. Similarly, Andrés Rodríguez-Pose discusses rural communities in the context of the places and people “that don’t matter”.[37] That is not to say that people in rural areas do not matter but rather, that many inhabitants of these locales have the perception that they do not matter in the context of national or supranational elites.[38] Thus, it is only natural that sections of society may feel disaffected and seek alternative political avenues to vent their frustrations.

Justifications for these perceptions come from a lack of access to infrastructure or resources; these feelings, valid or otherwise, erode social cohesion.[39] This is echoed somewhat in Europe by Scipioni and Tintori, who, in the context of EU integration, argue that in rural places, the urban elite had lost the people’s consent.[40] It is axiomatic that if part of the society does not consent, then the collective is weakened.

In addressing the second issue, the growth of discontent towards the elites, both national and EU, leaves openings for anti-democratic actions. Locales with anti-system representation also manifest a tendency towards populist leaders with weak democratic credentials.[41] Thus, there is a trend of autocratic leaders emerging and gaining space in local and national politics of the type that would have seemed impossible a generation ago.[42]

Populist leaders tend to oversimplify complex problems or ‘other’ groups within society, such as minorities or immigrants. Through the creation of out-groups and ’emergencies’, populist leaders set conditions to act outside democratic norms. Once this happens, it can be challenging for policymakers to stop democratic backsliding. At a state/regime level, this is of no consequence, but at the social and individual level, this is vital. Not for nothing are the happiest and most prosperous places in the world those that have a strong element of democratic participation and freedom. Consequently, from the perspective of defence and security—and this can be seen in the regimes of Erdogan, Orban, and Fico—anti-democratic populism is antithetical to cooperative security.

Populist leaders tend to oversimplify complex problems or ‘other’ groups within society, such as minorities or immigrants.

Finally, the rural-urban divide is—whether accepted or not—a locus for malign action. We are living in a time that Mark Leonard calls ‘the age of unpeace’ and experiencing what Mark Galeotti calls the ‘weaponisation of everything’. In this age, Western states are rent by hybrid warfare and grey-zone activities that seek to undermine the social fabric and collective security.[43] Whilst it might be comforting to disabuse this idea as one of paranoia and conspiracy, it is naïve to do so. Russian security services have long engaged in hybrid activities across Europe. Russian military and intelligence actors have long used the concept of Maskirovka to cover covert activities below the threshold of war: activities included assassination, political interference, and veiled threats.[44] In addition, whilst Europe is losing the information war against itself when it comes to the eminently beatable Russia, there seems to have been a forgetting that Chinese thinkers coined the phrase “unrestricted warfare” to cover the range of activities that they are also engaged in across Europe and the U.S.

Consequently, it becomes clear that if national leaders allow social discontent to fester in the way that it has in the recent past, western leaders may undermine the polities they are charged with protecting, as Michal Šimečka noted in discussing hybrid warfare and collective defence, “ultimately, the ability of any political order to withstand subversion or propaganda is a matter of governance and social cohesion.[45] For there to be collective security, there must be collective.

Building a Community of Belief

It must be clear that what is needed in Europe is a community of belief. Democractic Europeans need to understand that there are threats beyond the borders but that these threats are manageable. External threats are only existential to the degree that Europeans allow them to be—Russia cannot conquer Ukraine, nevermind Europe, and the PRC is at a safe remove.

To this end, European policymakers and populations need to shift away from the narrative of perma-, poly-, and omni-crisis; considerable cognitive energy must be placed on showing why Europe is desirable/a source of envy and why this must be protected. The narrative that Europe is in decline may have some truth, but just as “winning” is not “won”, decline is neither an end-state nor interminable. The idea that Europe is lost is undermined by the fact that to a vast swathe of people from the “arc of instability”, Europe is—all things considered—still a proverbial city on a hill. This positive appraisal applies equally to the US; after all, it is not for nothing that millions of Latin Americans risk death to get there.

Considerable cognitive energy must be placed on showing why Europe is desirable/a source of envy and why this must be protected.

Europe has long been a beacon of hope, and this is a threat to those whose only ‘power’ is that of destruction. As Booth noted in 1991, “while the Soviet Union can still wreck the world in some circumstances, it cannot attract a single immigrant”.[46] This was true then and remains largely true—replacing Russia for the Soviet Union—today. ‘Attractiveness’ is vital to developing positive emotions around an idea or concept to which an individual and, subsequently, a community might bond.[47] Emotion is vital, especially in the informational and communicative sense, as it is common practice for people to share what they are emotional about.[48]

Idealised schema of the micro-foundations of collective defence—modified ‘Coleman Boat’ by author.

In Safer Together, the EU report on enhancing Europe’s civilian and defence preparedness and readiness, Sauli Niinistö notes that “Security is the foundation on which everything is built”.[49] Thus, from this statement, it is no stretch to say that collective defence is a tool to provide societal security. With societal security as referent, it is less of a stretch to say that this is the primary public good. Consequently, it must be protected. It is somewhat telling that, at present, the Eurobarometer website does not even have a theme for defence and security—perhaps this will change with the publication of the Niinistö report.[50] However, it strikes at the age-old disconnect between the EU as a peace-building project and a provider of security, in the non-military sense. Across Europe, policymakers must recall that collective defence and sharing legal and democratic norms are fundamental for trust, and trust is foundational to social and economic progress and stability.[51]

Conclusion

For there to be collective defence, there must be a collective. For there to be a working collective, there must be a functioning democratic system—and this must be protected.

Returning to McSweeney, one final time—we are who we want to be.[52] Thus, we have choice—and we have agency. In discussing the centrality of the individual in ending the Cold War, “the Berlin Wall did not fall, it was pushed” [emphasis in original].[53] It was not an abstract structure that brought the end of the Cold War—it was a lustrous leviathan driven by human-level action, a collective sense of identity and interest, and a demonstrably superior level of living standards and human freedom that made attracted so many Warsaw Pact countries to the West. Likewise, a collective sense of identity and interest and attraction will be essential to renewing collective defence today.

Dermot Nolan holds Master’s Degrees in International Relations and International Security (from Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, the Netherlands) and Military History and Strategic Studies (from the National University of Ireland, Maynooth). Additionally, he served 12 years in the Reserve Defence Forces Ireland, where he served in the Artillery Corps. He has research interests in Cold War History, Land Warfare, and Nuclear Deterrence. The views contained in this article are the author’s alone.

[1] Camille Grand, (2024). “Defending Europe with less America”. European Council on Foreign Relations, 7-9, https://ecfr.eu/publication/defending-europe-with-less-america/.

[2] See Richard K. Herrman, (2013), “Perceptions And Image Theory In International Relations,” in Leonie Huddy (ed.) et al. The Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology (2nd ed), 334-364. See also, John Chilcot, (2016), The Report of the Iraq Inquiry (Executive Summary), The National Archives, 129-137.

[3] Olga Onuch, (2024), “Fighting for Europe: The EU’s Democratic Pull Phenomenon in Ukraine, Poland and Belarus,” Journal of Common Market Studies, November 10, 2024, 1430.

[4] Matthias Mader (2024), “Increased Support for Collective Defence in Times of Threat: European Public Opinion before and after Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine,” Policy Studies 45 (3–4): 406. For a fascinating look at public discontent at “non-democratic” security practices, see: Susan Colbourn, (2022). “Euromissiles: The Nuclear Weapons That Nearly Destroyed NATO,” (Ithaca, NY), 226-278.

[5] James Pamment & Elsa Isaksson (2024), “Psychological Defence: Concepts and Principles for the 2020s Psychological Defence Agency,” MPF Report Series 6/2024.

[6] Bill McSweeney, “Security, Identity and Interests,” (Cambridge) 86.

[7] Ken Booth, “Security and Emancipation,” Review of International Studies 17, no. 4, 318.

[8] James S. Coleman (1986), “Social Theory, Social Research, and a Theory of Action,” American Journal of Sociology. 91, no. 6; 1317.

[9] For discussion on the growth of coalition governments, see: LSE Blog (2024), “Balancing Act: How Coalition Governments Are Reshaping Democracy,” London School of Economics,

https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lseupr/2024/01/30/balancing-act-how-coalition-governments-are-reshaping-democracy/ and see also, Maria Thurk and Svenja Krauss, “The Formalisation of Minority Governments,” West European Politics 47 (1): 115-116.

[10] Janice Gross Stein, “Threat Perception in International Relations,” in Leonie Huddy (ed.) et al. The Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology (2nd ed), 364.

[11] John J. Mearsheimer, “The Tragedy of Great Power Politics,” (New York), 45-66.

[12] Vladimir Putin, (2007) Speech and the Following Discussion at the Munich Conference on Security Policy, February 10, 2007, President of Russia’s website: http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/24034.

[13] Pawel Swieboda, “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Pivot? Central Europe’s Worries About U.S. Foreign Policy,” Foreign Affairs, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/poland/2012-12-04/whos-afraid-big-bad-pivot.

[14] Lord Hastings Ismay, quoted in “NATO Leaders,” North Atlantic Treaty Organisation homepage: https://www.nato.int/cps/ge/natohq/declassified_137930.htm.

[15] Government of Sweden, “Total Defence,” https://www.government.se/government-policy/total-defence/defence-resolution-2025-20302/.

[16] Wolfgang Wagner, “Contesting Western Support for Ukraine. The Radical Left in the European Parliament,” Journal of European Integration, November 15.

[17] NATO Public Diplomacy Division (2024), Press release: Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014-2024), 4, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2024/6/pdf/240617-def-exp-2024-en.pdf.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Joseph Schumpeter quoted in Roger Beaumont (1973) Military Elites (New York), 191.

[20] Janice Gross Stein, “Threat Perception in International Relations,” 367.

[21] Tim Ripley, Operation Aleppo: Russia’s war in Syria, 20-28.

[22] Mark Galeotti, (2019) “We Need to Talk About Putin,” (London), 179.

[23] Garvan Walshe, The Beowulf Group: Taking the lead to defend Europe. European View, 0(0), 205.

[24] Dermot Nolan, “Conventional Armed Forces in the Cold War: The Key to Control?,”

The Defence Horizon Journal, November 11, 2021, https://tdhj.org/blog/post/cold-war-conventional-armed-force/.

[25] Booth, 1991, 313.

[26] Ekaterina Schulmann (2023), Bureaucracy as the Pillar of Stability: Are There Any Real Institutions Inside the Russian Political Regime?, Carnegie Politika, December 8, 2023.

[27] Mattia Sguazzini, and Matteo Mazziotti di Celso, “Unveiling Military Strategic Narratives on Social Media: A Civil–Military Relations Perspective,” European Security, November, 3.

[28] Jonah Berger, “Contagious: Why Things Catch On” (London), 24 and 72.

[29] Hilkka Grahn and James Pamment (2024), Exploitation Of Psychological Processes In Information Influence Operations Insights From Cognitive Science. Lund University Psychological Defence Research Institute Working Paper 2024:4, 9.

[30] Walshe, (2024), 207.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Booth, (1991), 315.

[33] Sarah Raine, (2017), Europe’s Strategic Future: From Crisis to Coherence? Adelphi Papers, 57, 41-69; see also: Marie Hyland, (2023), “Europe’s widening rural–urban divide may make space for far right,” European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/blog/2023/europes-widening-rural-urban-divide-may-make-space-far-right.

[34] For more, see the Rural Urban Divide in Europe (RUDE) homepage: https://www.norface.net/project/rude/.

[35] Matthew Schoene, (2018), European disintegration? Euroscepticism and Europe’s rural/urban divide, European Politics and Society, 20(3), 350.

[36] Nathalia Vigna, (2024), An urban–rural divide of political discontent in Europe? Conflicting results on satisfaction with democracy. European Political Science Review, 16(4), 610.

[37] Andrés Rodríguez-Pose, The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it), Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, Volume 11, Issue 1, March 2018, 189–209.

[38] Herrman, (2013), “Perceptions And Image Theory In International Relations,” 336.

[39] Trevor Brown, and Suzanne Mettler, (2022), The Growing Rural-Urban Political Divide and Democratic Vulnerability. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 699(1), 130.

[40] Marco Scipioni and Guido Tintori, (2021), “A rural-urban divide in Europe? An analysis of political attitudes and behaviour,” European Parliament, 19.

[41] Marie Hyland (2023), “Europe’s widening rural–urban divide may make space for far right,” European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

[42] Jan Philipp Thomeczek argues that when they get into power, left-leaning populists seem to moderate; however, this may be conditioned by the place and system to which such parties belong. Consequently, whilst right-wing populism is an issue for the here-and-now, ensuring that anti-democratic politics of all persuasions is nipped in the bud must be a priority for politicians. See: Jan Philipp Thomeczek (2024), Do European left-wing populists in government become more moderate? The Loop, ECPR Political Science Blog. https://theloop.ecpr.eu/european-left-wing-populists-in-government-become-more-moderate/.

[43] Wang Xiangsui, and Qiao Liang (1999), Unrestricted Warfare: Two Air Force Senior Colonels on Scenarios for War and the Operational Art in an Era of Globalization (Beijing), 8-15.

[44] Daniel P. Bagge (2019), Unmasking Maskirovka (Washington); for a more historical account, see also, Ladislav Bittman (1985), The KGB and Soviet Disinformation; An insider’s view. (Virginia), 35-70.

[45] Michal Šimečka, 2017, “Collective Defense in the Age of Hybrid Warfare,” Policy Paper, Institute of International Relations Prague. https://www.iir.cz/collective-defence-in-the-age-of-hybrid-warfare.

[46] Booth, (1991), 313.

[47] McSweeney, (1999), 171-173.

[48] Hilkka and Pamment, (2024), 7.

[49] Sauli Niinistö, (2024), “Safer Together Strengthening Europe’s Civilian and Military Preparedness and Readiness,” European Commission, 4.

[50] At present the themes laid out on the Eurobarometer website are: Agriculture and Fisheries, Climate Action and the Environment, Digital Society and Technology, Economy, Finance, Budget and Taxation, Education and Training, Employment, Energy, External Relations, Health and Food Safety, Industry, Competition and the Single Market, International Partnerships and Humanitarian Aid, International Trade and Customs, Justice and Home Affairs, Politics and the European Union, Regions and Regional Policy, Science, Space and Research, Society, Culture and Demography, and Transport and Mobility.

Eurobarometer, surveys by theme. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/browse/theme

[51] Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson (2012), “Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty,” (New York), 41-55.

[52] McSweeney (1999), 183-184.

[53] Ken Booth in Booth et al,. (1998), Statecraft and Security: the Cold War and Beyond (Cambridge), 7-8.