Abstract: In contrast to recent engagements at sea defined nearly exclusively by the logic of attrition, this paper argues that manoeuvre warfare is an essential component of naval warfare. The article shows that, depending on mission objectives, naval operations are characterised by manoeuvre warfare and thus contribute to minimising an adversary’s attempt to attrite one’s forces.

Problem statement: How to conduct naval operations under conditions of high-intensity warfare?

So what?: Western navies need to re-learn the skills of high-intensity naval warfare and how to make use of warfighting functions such as manoeuvre and fires to shoot first effectively and gain an advantage over the enemy.

Source: shutterstock.com/The Mariner 4291

Revolutionising Warfare?

At a leading European naval conference in 2024, one of NATO’s highest-ranking naval officers was asked whether developments in the war in the Black Sea would revolutionise naval warfare. In his response, the flag officer acknowledged the impressive results achieved by Ukraine in its approach to war at sea in this particular conflict scenario; however, he also emphasised the continuing significance of conventional naval operations, particularly in a blue-water context.[1] His statement was a valuable contribution to an ongoing discussion of naval warfare nurtured by the two most recent high-intensity conflicts in the maritime dimension: the Russo-Ukraine War and the Red Sea crisis. The focus of the debate has been a conflict party’s ability to degrade a naval opponent or to force an unfavourable cost-efficiency upon him—in both cases, through incremental attrition rather than sophisticated naval operations.[2]

Indeed, one should not dismiss the importance of novel features of naval warfare as demonstrated by the recent high-intensity conflicts, especially the massive use of uncrewed surface vehicles and aerial systems (USVs and UAS). However, it would be a mistake to overstretch the relevance of these conflicts. The way in which the conflicts in the Black and Red Sea are fought is the result of particular conditions which cannot be applied to the entire spectrum of naval warfare. Firstly, in the case of the war in Ukraine, the conflict takes place in a continental theatre of operations. Even for Russia—as the party in possession of the larger fleet—naval operations are secondary to land operations.[3] Secondly, both conflicts are fought on narrow seas, in the case of the Black Sea, even an enclosed sea. Various authors have elaborated on the differences between naval operations in blue water and the narrow seas.[4] Following the theories developed by these authors, the war in the Black Sea demonstrated that land-based systems played a pivotal role in tracking, targeting and destroying assets at sea.

One should not dismiss the importance of novel features of naval warfare as demonstrated by the recent high-intensity conflicts, especially the massive use of uncrewed surface vehicles and aerial systems.

Ultimately and most importantly, both Ukraine and the Houthis—in the Red Sea—have had to conduct naval operations without conventional naval assets capable of high-intensity warfare. Resorting to asymmetric means and ways is a rational decision for these conflict parties. Nevertheless, due to their peculiarities, the case studies of the Russo-Ukraine War and the Red Sea should not serve as the predominant framework for analysis of naval scenarios which involve parties that actually do operate navies capable of fighting in a multidimensional environment.

Manoeuvre Warfare in Naval Theory and Practice

It is difficult to apply the ongoing land-centric discussion on the viability of manoeuvre warfare in the post-2022 era to the naval dimension. To begin with, there are some significant general differences between the principles of action-guiding armed forces in the naval and land domains, for example, as far as the benefits of defence are concerned.[5] Concerning manoeuvre warfare, the differences are particularly striking, making the universal application of concepts across service branches problematic. Concepts such as pre-emption, dislocation (the removal of opposing forces from decisive points on the battlefield) or disruption (the neutralisation of the enemy’s centre of gravity, ‘preferably by attacking […] through enemy weaknesses’) are essential elements in manoeuvre warfare theory.[6] However, naval warfare has no frontlines to break nor opposing forces to be surrounded. In general, the meaning of space and position in war at sea differs from land warfare. As Wayne P. Hughes Jr. and Robert Girrier argue, ‘At sea [sic] the predominance of attrition over manoeuvre is a theme so basic that it runs throughout this book. Forces at sea are not broken by encirclement; they are broken by destruction.’[7]

At sea, the predominance of attrition over manoeuvre is a theme so basic that it runs throughout this book. Forces at sea are not broken by encirclement; they are broken by destruction.

The way in which this destruction can be accomplished, however, may demonstrate features of manoeuvre warfare or—what the British 2011 Maritime Doctrine refers to as ‘Manoeuvrist approach to operations.’[8] For example, eliminating an opponent’s logistical support vessels and other high-value targets may decisively weaken the enemy’s centre of gravity without the need to destroy every single warship the opponent operates. As Milan Vego elaborates, skilful application of operational art may provide a capable naval force with the instruments to defeat a stronger opponent and thus evade the destiny of having to degrade an enemy through sheer numbers—the quintessence of attrition warfare. In a major naval operation, naval forces are employed to accomplish an operational or strategic objective in a maritime theatre following an operational idea and common plan.[9] Ideally, by designing and skilfully executing superior plans, the operational commander aims to ‘prevent attrition warfare from becoming a predominant feature of war at the operational and strategic level.’[10] As Vego argues, the only alternative method of destroying enemy naval forces, at least as far as the inferior fleet is concerned, is attrition warfare, which aims to avoid a major engagement with the hostile fleet and instead seeks to attack the opposing fleet through a series of minor tactical actions whenever favourable circumstances exist.[11] The U.S. Naval Doctrine Publication 1 also applies an operation-centric understanding but further stresses that ‘using the philosophy of manoeuvre warfare, we destroy or eliminate an adversary’s centre of gravity indirectly by attacking weaknesses or vulnerabilities vital to his source of power. One method of indirect attack is to create a dilemma by putting the enemy in a situation where any step taken to counteract one threat increases his vulnerability to another. This is an indirect approach.’[12]

Apart from understanding manoeuvre warfare as a warfighting philosophy,[13] the second meaning, which matters when discussing the current significance of manoeuvre in naval warfare, refers to the term’s meaning as an essential element of naval tactics and operations. According to Hughes Junior and Girrier, the essential foundation of all naval tactics has been to attack effectively using superior concentration and to do so first, either with longer-range weapons, an advantage of manoeuvre, or shrewd timing based on good scouting.[14]

During the age of sail, manoeuvre was the quintessence of naval tactics. Superior manoeuvring of naval formations was essential to winning battles. Manoeuvring involved positioning one’s fleet to sail to the leeward or the windward, depending on tactical choices, breaking through the opponent’s column and shooting at ships from an advantageous angle or doubling an enemy’s column.[15] If decisive victories were to be achieved, formation commanders could aim to manoeuvre their formation to leeward of the opponent, thus ‘denying them the option of retreat, and then concentrate a superior force on part of their formation.’[16] This period of manoeuvre battles, which lasted approximately 200 years, came to an end during the First World War. In the age of long-range, high-speed and air-launched weapons and advanced methods of scouting, the relative position of the sea-based platform to its respective target was no longer the single most important element of naval tactics.[17]

If decisive victories were to be achieved, formation commanders could aim to manoeuvre their formation to leeward of the opponent.

Nevertheless, while manoeuvre ceased to be the central function in naval warfare it once was about a century ago, it remains an important element of naval tactics. In Hughe’s and Girrier’s definition of both operational trends and constants,[18] manoeuvre plays a pivotal role. As far as trends are concerned, Hughes defines naval tactics as being built on five propositions. For this article, two of Hughe’s propositions—attrition and manoeuvre—are considered. Hughe defines that ‘maneuver is the activity by which command-and-control positions forces to scout and shoot.’[19]

Given that weapon and sensor ranges dominate war at sea, the range and bearing between naval forces is a principal tactical consideration. Establishing a relative position to deliver firepower requires a naval force’s timely, coordinated, and collective positioning. However, as weapon systems have evolved, the speed and manoeuvrability of weapons and scouting—the early detection of the enemy—have increased in importance in comparison with the relative position of the two naval formations. Still, according to Hughes and Giuseppe Fioravanzo, seeking to manoeuvre one’s force in a favourable tactical position that ‘affords the earlier or greater concentration of firepower’ remains a constant in naval history.[20]

Ultimately, manoeuvre warfare in naval campaigns is understood as the sum of all necessary fleet movements to achieve the respective objective—either strategic, operational, or tactical.[21] At the strategic level of war, mobility is the key word, describing the ability ‘to move long distances in a self-sustaining manner, […] quickly in relation to the movement of ground forces [and] to operate at length, up to several months on or near station.’[22] Operationally, deployment is the key term, meaning attaining given positions in a timely manner. Although, at first sight, positions at sea seem not to be fixed geographically, there are indeed a considerable number, such as seaports of em-/debarcation (SPOE/Ds), maritime chokepoints or areas relevant for anti-submarine warfare (ASW).[23] The purpose of such operational deployments is the provision of maritime combat capabilities.[24]

Another aspect that is especially relevant with regard to the function ‘manoeuvre’ assumes in naval operations concerns the relationship between manoeuvre, attrition, and the objective to be accomplished. The operational objective derives from the higher (strategic) commander’s intent and, therefore, provides direction and guidance for the deployment of forces. In many cases, the operational objective is more or less establishing sea control or sea denial in assigned areas for a given time frame. In these cases, attrition warfare by any means is the prerequisite for achieving the objective; manoeuvring the asset or formation to employ its firepower (attrition) supports accomplishing this objective.[25] In contrast, maritime sealift [military sea lift] and amphibious operations are two types of naval operations in which attrition supports manoeuvre. Firstly, maritime sealift—the safe and timely arrival or departure of maritime traffic at or from a SPOD / SPOE. The prominent characteristic of these operations is the need to manoeuvre, in addition to force protection. Allied convoy operations during the Second World War are a historical example. Secondly, amphibious operations require extensive manoeuvring before the task, mainly amphibious demonstration, rehearsal, or assault, can be executed.

Maritime sealift and amphibious operations are two types of naval operations in which attrition supports manoeuvre.

At the tactical level, employment is the keyword, meaning the assignment of tasks to forces and/or direction and control, i.e., positioning these forces to accomplish the assigned tasks. There are eight basic naval tactics: five are agility/manoeuvre-related, and three are attrition-related.[26]

Analyses of Anticipated Conflict Scenarios

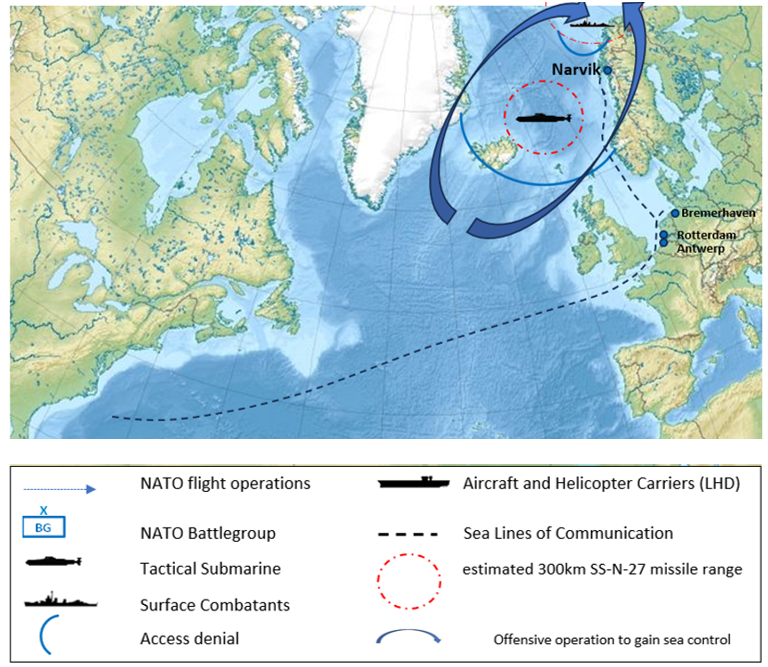

The following section examines two conflict scenarios: one in the Atlantic Ocean and one in the Mediterranean Sea. Given the strategic importance of these respective theatres for communications and power projection, these would likely see significant naval activities in case of a major confrontation between Russia and NATO.[27]

Transatlantic Scenario: Protecting the Sea Lines of Communications (SLOCs)

Not too dissimilar from the situation during the Cold War,[28] a high-intensity conflict involving NATO and the Russian Federation in Europe would involve the transportation of large amounts of personnel and materiel from North America to Europe to reinforce and sustain NATO’s capabilities on the European continent.[29] Over the past decade, NATO has re-established and strengthened many capabilities necessary for protecting transatlantic SLOCs and conducting naval operations in the transatlantic theatre.[30] Anticipating a situation that strategically requires establishing and maintaining continuous logistic support for forces operating in central and eastern Europe, the operational objective for NATO’s maritime forces would be the safe and timely arrival of cargo vessels to dedicated SPODs on the European mainland. To use strategic mobility as its overarching purpose, such a naval operation would be characterised by extensive manoeuvring activities. The danger Russian naval forces, especially subsurface forces, pose to vessels and ports serving NATO has been addressed by multiple authors in recent years.[31] However, scholars tend to disagree to a certain degree on the Russian course of action (COA).[32] Moreover, the difficulties the Russian military has faced since the outbreak of the Russo-Ukrainian War in targeting and neutralising military equipment once it has been delivered is brought forward as another argument as to why Russia may seek to degrade NATO’s military capabilities through attrition as long as the military hardware is still transported at sea.[33] To minimise the threat to NATO’s shipping and military forces, two possible COAs for NATO naval forces are possible.

The difficulties the Russian military has faced since the outbreak of the Russo-Ukrainian War in targeting and neutralising military equipment once it has been delivered is brought forward as another argument as to why Russia may seek to degrade NATO’s military capabilities through attrition as long as the military hardware is still transported at sea.

The first would be an offensive, attrition-centric approach by establishing sea control in areas outside the opponent’s effective sensor and weapon ranges, hence destroying or neutralising offensive capabilities. In light of the opponent’s order of battle, this COA would require superior forces with sufficient organic logistic support to ensure a persistent presence.

The second COA would be somewhat defensive or manoeuvre-centric by directing maritime traffic beyond the threat and conducting sea control or sea denial[34] in specific areas, such as the Greenland Iceland UK (GIUK)[35] gap or the approaches to the North Sea, essentially establishing a layered defence. Such a COA would emphasise the function of ‘manoeuvre’ over the employment of firepower. Attacks by NATO forces against Russian military targets would only occur if and when necessary.

As far as the understanding of manoeuvre warfare as a warfighting philosophy is concerned, the transatlantic scenario is characterised by both manoeuvre and attrition. Both COAs demonstrate ample potential for a ‘manoeuvrist approach’ with regard to the exploitation of critical vulnerabilities to weaken the opponent’s centre of gravity. One example includes the neutralisation of the opponent’s abilities to scout. Establishing and maintaining a recognised maritime picture (RMP) in sea zones as vast as those involved in a transatlantic scenario is difficult, especially under wartime conditions. While the three-dimensional picture compilation process is a significant challenge to NATO, for Russia, whose territory is far away, creating an RMP for sea zones of relevance in a transatlantic scenario is even more difficult. However, establishing an RMP is especially important for submarine operations, given limited submarine sensor ranges and dependence on external sensor data, particularly if a submarine is tasked to employ long-range cruise missiles.[36] In this context, long-range maritime patrol aircraft (one of the principal scouting assets of the Russian fleet) and aircraft operated by the Russian Aerospace Force’s long-range aviation will play an important role in intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) and have been conducting reconnaissance flights throughout the Norwegian Sea and up to the North Sea.[37] Consequently, these air-borne assets capable of scouting and employing weaponry would likely be a high-priority target for NATO air assets on the northern flank.

Moreover, recent deployment patterns by NATO militaries at the northern flank demonstrate elements of a naval strategy which can be associated with indirect/manoeuvre warfare. During the 1980s, the concept behind NATO’s offensively oriented concept of maritime operations (CONMAROPS) foresaw the Soviet fleet having to hold back to defend its Arctic bastion[38] rather than giving the Soviets the initiative to deploy their forces offensively.[39]

During the 1980s, the concept behind NATO’s offensively oriented concept of maritime operations foresaw the Soviet fleet having to hold back to defend its Arctic bastion rather than giving the Soviets the initiative to deploy their forces offensively.

In light of recent deployments of NATO naval forces to the high north and a much smaller Russian fleet,[40] the dilemma facing Russian naval planners in the 2020s is one of offensive employment of firepower against NATO member states’ critical infrastructure, SPODs and interference with SLOCs vs. defensive use of naval assets against NATO military capabilities. This is a more extensive challenge than that of the 1980s. Furthermore, NATO’s actions blend well with the U.S. Naval Doctrine’s definition of manoeuvre warfare ‘by putting the enemy in a situation where any step taken to counteract one threat increases his vulnerability to another.’[41]

In contrast with these manoeuvrist elements, both NATO COAs associated with the transatlantic scenario would instead fall into Vego’s categorisation of attrition warfare. A transatlantic scenario would likely consist of a prolonged series of minor tactical actions. These may be an evasive manoeuvre of a convoy, the defence of a SPOD, the offensive hunt for and destruction of a Russian submarine or the interception of a Russian maritime patrol aircraft scouting over the Norwegian Sea. The accomplishment of the campaign’s mission[42] and, whether by choice or necessity, the destruction of Russian naval capabilities to interfere with NATO’s maritime communications would likely not be the result of a few short and sharp battles. Unlike, for example, the Arab-Israeli War of 1973,[43] such a scenario would rather likely result in a cumulative campaign that would attrite the Russian side’s naval strength. Maritime manoeuvre can make important contributions to minimising NATO forces’ attrition in such a prolonged campaign.

Source: Uwe Dedering, ‘North Atlantic Ocean laea relief location map,’ 04 December 2010, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vorlage:Positionskarte_Nordatlantik#/media/Datei:North_Atlantic_Ocean_laea_relief_location_map.jpg, accessed on 18 August 2024, CC BY-SA 3.0.

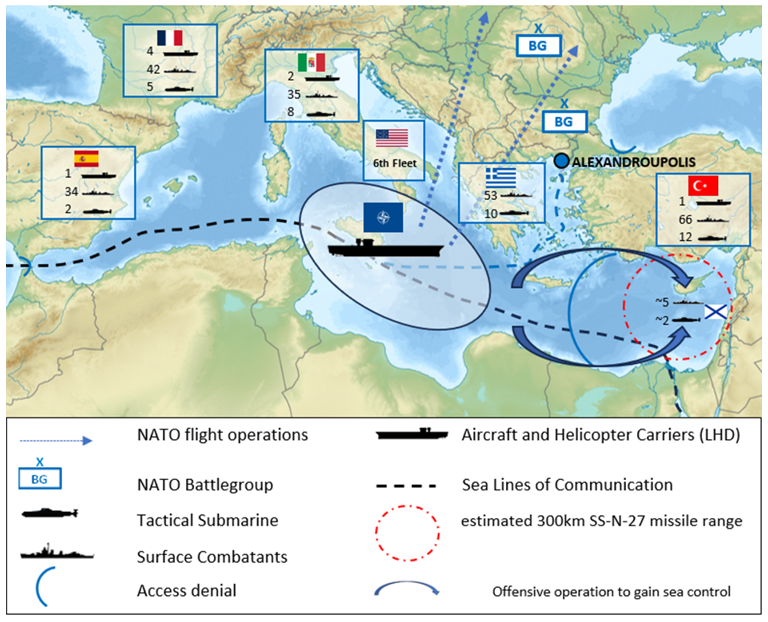

Mediterranean Scenario: Establishing Sea Control

The second conflict scenario under consideration takes place in the Mediterranean Sea. This naval theatre of operation is characterised by two factors that will likely shape naval operations in a high-intensity scenario. The first is narrow maritime geography. Russia’s Standing Operational Formation of the Russian Navy in the Mediterranean Sea is geostrategically isolated as it is separated from the home bases of the Russian Black Sea Fleet, its principal force provider, by the Turkish Straits.

The second factor that would impact how naval operations would likely develop in case of a hypothetical war is NATO’s considerable superiority in forces in the Mediterranean. Not taking the unusually high concentration of Russian warships in the time period preceding February 2022 and the unusually low number of Russian naval vessels since the Russo-Ukraine War (see further below) into consideration, on average, Russia’s naval formation in the Mediterranean consists of approximately ten units, among them two submarines and a few support ships.[44] In a high-intensity conflict, these Russian warships would be confronted with a NATO Armada. NATO naval forces would not only consist of the alliance’s Standing NATO Maritime Group 2—which regularly patrols the waters of the Mediterranean Sea. NATO forces would be the combined strength of the Italian and Greek navies, substantial parts of the French and Spanish navies, the majority of the Turkish Navy, various assets of smaller NATO states and the U.S. Sixth Fleet. In total, a force posture of more than 200 naval vessels would likely be available to NATO in the Mediterranean—not counting reinforcements from other regions such as North America or the Persian Gulf.[45]

NATO naval forces would not only consist of the alliance’s Standing NATO Maritime Group 2—which regularly patrols the waters of the Mediterranean Sea.

In contrast with the prolonged transatlantic scenario and in light of the vast discrepancy in military strength between the opponents, in this scenario, a major naval operation following Vego’s definition appears to be a rational possibility, especially given the geostrategic isolation of the Russian naval formation and the significance of the Mediterranean Sea for SLOCs.

Again, two COAs are possible for NATO planners. The first would involve detecting, tracking and destroying the Russian naval formation in the Mediterranean (and potentially some land-based assets in Syria) in a ‘fast and furious’ naval battle.[46] Following the destruction of the Russian naval presence in the Eastern Mediterranean, NATO could realistically aim to achieve sea control.

Recent naval exercises by NATO demonstrate that the combined NATO member states are in possession of sufficient capabilities to carry out offensive military operations at NATO’s eastern flank. Since 2021, for example, NATO has trained its capabilities to employ firepower to achieve effects across Europe in the Baltic Sea based on sea-based assets in the Mediterranean. A particularly striking example was the exercise ‘Neptune Strike 2023’, which involved, among others, three aircraft carriers simulating two attack operations. According to the Bundeswehr Centre for Public Affairs, it was the first time three aircraft carriers under NATO command and control had trained attacks of this kind. Moreover, for a period of several days, a fourth carrier strike group centred around the French Charles de Gaulle joined the exercise to practice offensive and defensive operations.[47]

The second COA would see NATO deploying naval and air forces to carry out sea denial operations eastward a line Rhodes-Crete-Eastern North Africa to prevent the Russian naval formation in the Mediterranean from deploying and taking action against NATO.

Nevertheless, in cases of both COAs, containing the Russian naval assets in the easternmost corner of the Mediterranean Sea and thus neutralising the Russian warships by access denial or actual physical destruction of the Russian Mediterranean formation, a fleet action by NATO’s much superior forces against Russia’s standing formation in the Mediterranean would probably be comparatively swift and decisive in reducing the threat potential posed by the Russian naval presence at NATO’s southern maritime flank and allow NATO to establish and exploit sea control in the Central Mediterranean.

Both COAs would include elements associated with a manoeuvrist approach to operations as they very likely may also take advantage of critical vulnerabilities to decrease Russian strength. With near certainty, in case of war with Russia, the Turkish and Greek navies would be deployed to guard the Turkish Straits and prevent any possible Russian breakout. The geographical isolation of the Russian Navy’s formation in the Mediterranean would then be complete. As the example of the Russo-Ukraine War demonstrates, without access to the Turkish Straits, the Russian Navy faces great difficulty sustaining its naval force in the Black Sea. Shortly before Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, a massive concentration of Russian naval assets in the Mediterranean was reported. Between 16 and 29 naval vessels, among them two Slava-class cruisers, were reported to have been assembled in or temporarily deployed to the Mediterranean.[48] One and a half years into the war and without the opportunity to sufficiently supply forces at sea and the Russian logistical supply point in Tartus, Syria, this number has supposedly dropped to six—including two auxiliaries—by October 2023.[49] This is a formation size far below the average demonstrated during the 2010s. Thus, by deploying its forces, NATO could potentially seriously weaken Russia’s naval formation in the Mediterranean using an indirect approach associated with comparatively little risk of suffering attrition of its own forces.

Shortly before Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, a massive concentration of Russian naval assets in the Mediterranean was reported.

Furthermore, based on the Russian military’s performance in the Russo-Ukrainian War, Sidharth Kaushal assesses that the Russian armed forces suffer from severe command and control issues at the joint level. This may reflect challenges in the stated desire to aggregate information from multiple service branches without reaching back to a higher headquarters or involving multiple separate command chains.[50]

In light of the limited long-range air defence capability of most small surface combatants, which make up the bulk of the Russian naval arms procurement programme, the lack of sea-based naval aviation and the retirement or wartime loss of Russian major surface combatants, the Russian fleet’s limited area air defence capabilities appear to be a critical vulnerability. Consequently, when discussing the impregnability of the Russian Anti-Access/Area Denial bubble, commentators often refer to the lethality of Russian land-based systems, such as the vaunted S-400 (SA-21 Growler) air defence system.[51] Providing air cover for a naval formation out at sea from land-based air defence systems and air assets involves at least three different branches of the armed forces—the Russian Navy, Air Force and Air and Missile Defence Forces—and well-practised operating procedures. For example, naval, land, and air assets have to contribute towards compiling a comprehensive air picture, target hand-overs have to be well orchestrated, and air operations must be harmonised to prevent blue-on-blue engagements. As various examples of Russian fighter aircraft being supposedly shot down by Russian air defence during the Russo-Ukraine War have demonstrated,[52] the Russian military appears to have problems with precisely these kinds of coordination among the service branches. NATO forces may exploit this critical vulnerability and minimise their own losses by engaging the enemy at its weak spot: inter-service area air defence.

As far as the second understanding of manoeuvre is concerned, a high-intensity conflict in the Mediterranean would involve attaining several areas and positions to be attained by manoeuvre warfare to ensure unhampered use for combined operational purposes or to prevent own forces from attrition. On the strategic level, strategic mobility would also play an important role—albeit likely a somewhat smaller one as in northern Europe—as inter-theatre SLOCs would ensure the transportation of supplies and reinforcements to NATO’s southeastern front. This has become particularly relevant since NATO battlegroups have been stationed in Bulgaria, Hungary, Slovakia, and Romania. Additionally, the U.S. has been expanding logistical capabilities at the port of Alexandroupolis, Greece, to serve as a logistical support hub in southeastern Europe.[53]

The U.S. has been expanding logistical capabilities at the port of Alexandroupolis, Greece, to serve as a logistical support hub in southeastern Europe.

On the operational level, such a scenario would involve significant deployments of forces. Operations would involve the manoeuvring of suitable assets to guard Mediterranean SLOCs and, given the grave threat posed by Russian cruise and ballistic missiles, to protect ports, bases, command posts and ships. Further deployments also seem reasonable from a NATO perspective. Apart from blocking the Bosporus approaches and the Suez Canal, deploying forces to monitor the Strait of Gibraltar—one of the far approaches (dal’nie podkhody) in Russian military terminology—would be mandatory to deny the Russian Navy access to this crucial body of water and contribute to isolating the naval theatre of operations.[54]

At the tactical level, NATO naval forces would be manoeuvred into positions where they could employ their firepower following NATO’s operational plans. As Rear Admiral William Houston, the deputy commander of the U.S. 6th Fleet, points out, already during peacetime, the U.S. deploys attack submarines “in this eastern portion of the Mediterranean to counterbalance the Russia [sic] buildup in Syria.” Commenting on the 2019 deployment of the Ohio-class submarine USS Florida in close proximity to the Russian Mediterranean formation, U.S. subsurface forces were supposedly “watching them [the Russian military presence – authors’ note] very, very closely. There’s really not a day where we’re not watching them every single day.”[55]

Given that at least the U.S. Navy, and potentially other NATO navies as well, are manoeuvring (pre-positioning) their navies to scout during times of peace and tension, there is little doubt that they would manoeuvre their units in position to employ their weaponry against the Russian vessels once hostilities started. Furthermore, depending on NATO’s operational plan, once the threat by the Russian naval formation in the Mediterranean was neutralised, full operational freedom in the central Mediterranean could be exploited to manoeuvre units in position to carry out sea-based strike operations aimed at the eastern part of Europe as practised during the ‘Neptune Strike’ exercise series.

Sources: IISS, ‘The Military Balance,’ Volume 124, No. 1 (2024).; CSIS, ‘3M-54 Kalibr/Club (SS-N-27),’ MissileThreat, https://missilethreat.csis.org/missile/ss-n-27-sizzler/, accessed on 18 August 2024; Nzeemin, ‘Relief Map of Mediterranean Sea,’ Wikipedia, 27. February 2023, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vorlage:Positionskarte_Mittelmeer#/media/Datei:Relief_Map_of_Mediterranean_Sea.png, accessed on 18 August 2024, CC BY-SA 3.0.

A Combination of Manoeuvre and Attrition

Manoeuvre, both as a warfighting philosophy and as a function in naval warfare, retains its importance even under 21st-century conditions. Only through the combination of attrition and manoeuvre can sea control be denied, accomplished and exploited and the naval forces of the opponent be neutralised. Attrition and manoeuvre mutually support each other, with one of the two functions being dominant and the other supporting, depending on the concrete type of mission. To accomplish the objective, naval forces have to be manoeuvred into positions to scout or employ firepower. To win, they have to do so faster and more effectively than the opponent. This, however, requires well-trained, highly professional sailors capable of carrying out naval operations under the conditions of high-intensity warfare.

Unfortunately, following the end of the Cold War, many navies lost some of their abilities to carry out complex wartime naval operations. Consequently, navies need to ‘re-learn war’ and implement the characteristics of modern and future naval warfare in doctrines, tactics, procedures and training. They should do so now, while the anticipated scenarios examined in this article are still only hypothetical scenarios and not yet gruesome reality.

Lieutenant Commander Dr. Tobias Kollakowski is a research fellow at the German Institute for Defence and Strategic Studies. His research focus is on Russian naval strategy, East Asian maritime affairs, and maritime security and strategy.

Commander Rainer Preuß serves as a department head at the German Maritime Warfare Centre. He specialises in non-kinetic naval warfare and the development of tactics.

Lieutenant Commander Stefan Glufke serves as a department head at the German Maritime Warfare Centre. He specialises in maritime uncrewed systems and the development of tactics.

The views contained in this article are the authors’ alone and do not represent the views of the Bundeswehr [Armed Forces of the Federal Republic of Germany], the German Ministry of Defence or the German Institute for Defence and Strategic Studies.

[1] Authors’ notes taken at the conference, June 2024.

[2] Paul McLeary, Joe Gould and Connor O’Brien, “Cost rising for US as it fights off Houthi drones,” Politico, last modified July 08, 2024, https://www.politico.com/news/2024/08/07/houthi-yemen-defense-iran-airstrikes-00173096; Wes Rumbaugh, “Cost and Value in Air and Missile Defense Intercepts,” CSIS, last modified February 13, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/cost-and-value-air-and-missile-defense-intercepts; Sheba Intelligence, “The Red Sea Chaos and the War of Attrition,” last modified February 12, 2024, https://shebaintelligence.uk/the-red-sea-chaos-and-the-war-of-attrition; David Axe, “Ukrainian Missiles Are Blowing Up The Black Sea Fleet’s New Missile Corvettes Faster Than Russia Can Build Them,” Forbes, last modified May 21, 2024, https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidaxe/2024/05/21/ukrainian-missiles-are-blowing-up-the-black-sea-fleets-new-missile-corvettes-faster-than-russia-can-build-them/.

[3] Following Russia’s failure to capture Kyiv, neutralise the Ukrainian military and cut Ukraine’s sea lines of communication during the initial stages of the war, naval operations may also be interpreted as tertiary to the development of the war. The war on the ground and Russia’s air campaign that aims to destroy Ukraine’s critical infrastructure can be seen as more relevant to the conflict (Comment by Nolan Dermot on 22 August 2024).

[4] Hermann Kirchhoff, Seemacht in der Ostsee: Ihre Einwirkung auf die Geschichte der Ostseeländer im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert, Volume 1 (Kiel: Verlag von Robert Cordes, 1907), III, 1-2; Edward Wegener, “Die Elemente von Seemacht und maritimer Macht, ” 29, In Seemacht und Außenpolitik, eds. Dieter Mahne and Hans-Peter Schwarz ((Frankfurt am Main: Alfred Metzner Verlag 1974), 25-58; Milan N. Vego, Naval Strategy and Operations in Narrow Seas, 2nd ed. (Abingdon: Frank Cass Publishers, 2003); Wayne P. Hughes Jr. and Robert P. Girrier, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 3rd ed. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2018), 161-162; Geoffrey Till, Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-first Century, 4th ed. (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018) 93-96, 156.

[5] Hughes and Girrier, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 166.

[6] Robert R. Leonhard, The Art of Maneuver: Maneuver-Warfare Theory and AirLand Battle (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1991), 19-20.

[7] Hughes and Girrier, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 19.

[8] U.K. Ministry of Defence, “Joint Doctrine Publication 0-10: British Maritime Doctrine,” August 2011, item 229, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a82d74440f0b62305b94a14/archive_doctrine_uk_maritime_jjd_0_10.pdf.

[9] Milan Vego, “On Major Naval Operations,” 94-95, Naval War College Review, 60, no. 2 (Spring 2007), 94-126.

[10] Milan Vego, Operational Warfare (U.S. Naval War College 2000), 3-4.

[11] Vego, Naval Strategy and Operations in Narrow Seas, 147-183; Vego, “On Major Naval Operations,” 121.

[12] Department of the Navy, “Naval Doctrine Publication 1: Naval Warfare,” March 28, 1994, 40, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-D207-PURL-LPS2123/pdf/GOVPUB-D207-PURL-LPS2123.pdf.

[13] ‘Manoeuvrist approach to operations’ in British terminology; U.K. Ministry of Defence, “Joint Doctrine Publication 0-10: British Maritime Doctrine,” idem., 229.

[14] Hughes and Girrier, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 33.

[15] Andrew Lambert, War at Sea in the Age of Sail (London: Cassell, 2000), 41; Hughes and Girrier, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 32, 39.

[16] Andrew Lambert, War at Sea in the Age of Sail, 41.

[17] John Creswell, British Admirals of the Eighteenth Century: Tactics in Battle (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1972), 7; Hughes and Girrier, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 172.

[18] Constants are defined as “practices that have not changed over the centuries of naval operations and so are not likely to change in the future.” In contrast, Hughes defines trends as “developments that have changed in one direction and so are likely to continue in the same direction in future operations;” Hughes and Girrier, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 129.

[19] Hughes and Girrier, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 168.

[20] Hughes and Girrier, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 170-171, 192; Giuseppe Fioravanzo, A History of Naval Tactical Thought, translated by Arthur W. Holst (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1979), 209.

[21] There is no consensus on this definition. The understanding of what defines ‘manoeuvre’ and ‘movement’ may vary in literature and among the navies of the world.

[22] Hughes and Girrier, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 171.

[23] For example, ‘Theatre ASW.’

[24] Capabilities that involve ASW, “Anti-Air Warfare” (AAW), “Anti-Surface Warfare” (ASuW), “Mine Warfare” (MW), “Amphibious Operations” (AmphOps), “Electromagnetic Warfare” (EW) and “Information Warfare” (IW).

[25] Jeffrey R. Cares and Anthony Cowden, Fighting the Fleet: Operational Art and Modern Fleet Combat (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2021), 52-71.

[26] Agility/Manouvre-related: ‘superior effort at the key point,’ ‘right distance,’ ‘surprise,’ ‘time,’ ‘concentration vs. dispersal’; attrition-related: ‘firing effectively first,’ ‘using asymmetry,’ ‘mixing fires.’

[27] For a discussion of the importance of the North Atlantic’s sea lines of communication, see, for example, James Stavridis, “VI. The United States, the North Atlantic and Maritime Hybrid Warfare,” In Whitehall Papers: NATO and the North Atlantic: Revitalising Collective Defence, ed. John Andreas Olsen, 87, no. 1 (2016), 92-101; Magnus Nordenman, The New Battle for the Atlantic: Emerging Naval Competition with Russia in the Far North (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019), 170; For the role of the North Sea as an assembly area for NATO platforms capable of power projection, see, for example, the 2021 deployment of the amphibious assault ship USS Iwo Jima, the 2023 deployment of the aircraft carrier USS Gerald R Ford and the 2024 deployment of the amphibious assault ship USS Wasp (U.S. Military Sealift Command, “North Sea Trio,” last modified May 09, 2021, https://www.msc.usff.navy.mil/Press-Room/Photo-Gallery/igphoto/2002641363/; Nina Berglund, “US and Norway mounted a show of force in the North Sea,” News In English, last modified May 23, 2023, https://www.newsinenglish.no/2023/05/23/us-norway-show-force-in-north-sea/; U.S. Navy, “Skagen Welcomes USS Wasp,” last modified June 13, 2024, https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/News-Stories/Article/3805592/skagen-welcomes-uss-wasp/); For the significance of the Mediterranean as a sea-zone where the Russian Navy has forward-deployed platforms equipped with land-attack cruise missiles, see, for example, Dmitry Gorenburg, “Russia’s Naval Strategy in the Mediterranean,” No. 35 (2019), Marshall Center, https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/security-insights/russias-naval-strategy-mediterranean-0; Ian Williams (2017), “The Russia – NATO A2AD Environment,” Missile Threat, Center for Strategic and International Studies, https://missilethreat.csis.org/russia-nato-a2ad-environment/.

[28] During the Cold War, for example, NATO carried out a series of annual military exercises called ‘Reforger’ (Return of Forces to Germany). The purpose of these exercises was to train the movement of military forces across the Atlantic and their deployment to the likely battlefields of West Germany; Michael Greenberg and Benjamin Phocas, ‘Return to Reforger: A Cold War Exercise Model for Pacific Deterrence,’ Modern War Institute, May 28, 2024, https://mwi.westpoint.edu/return-to-reforger-a-cold-war-exercise-model-for-pacific-deterrence/.

[29] U.S. European Command Public Affairs, “USEUCOM logisticians wargame force movements, sustainment with NATO counterparts,” November 18, 2022, https://www.eucom.mil/pressrelease/42235/useucom-logisticians-wargame-force-movements-sustainment-with-nato-counterparts, last modified on 12 August 2024; Eric Grove, “NATO as a maritime alliance in the Cold War,” 577, In The Sea in History – the Modern World, eds. Nicholas A.M. Rodger and Christian Buchet (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2017), 574-583.

[30] Sam LaGrone, “U.S. 2nd Fleet Declares Operational Capability Ahead of Major European Exercise,” USNI News, last modified May 29, 2019, https://news.usni.org/2019/05/29/u-s-2nd-fleet-declares-operational-capability-ahead-of-major-european-exercise; NATO, “NATO’s new Atlantic command declared operational,” last modified September 17, 2020, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_178031.htm; Nathan Gain, “RAF Poseidon MRA Mk1 MPA reaches Initial Operating Capability,” Naval News, April 03, 2020, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2020/04/raf-poseidon-mra-mk1-mpa-reaches-initial-operating-capability/; Magnus Nordenman, The New Battle for the Atlantic: Emerging Naval Competition with Russia in the Far North (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2019), 169.

[31] In addition to the traditional threat by Soviet/Russian submarine-launched surface-to-surface missiles and torpedoes to NATO SLOCs, authors have drawn attention to the Russian Federation’s newest generations of submarine-launched, substrategic missiles in the wake of the ‘kalibrisation’ of the Russian Navy during the 2010s. According to this interpretation, by using these long-range missiles, the Russian Navy would no longer need to close in on NATO convoys to cause significant damage to NATO’s reinforcement efforts.

[32] Authors disagree on the likelihood of the Russian Navy trying to wage a new ‘Battle of the Atlantic’ against NATO SLOCs. According to some interpretations, Russian subsurface forces are a serious threat to the North Atlantic. Another school of thought views a major Russian subsurface campaign in the North Atlantic as unlikely and perceives the Russian naval force posture much more defensively-oriented; Nordenman, The New Battle for the Atlantic, 137-140; Steve Wills, “These aren’t the SLOCs you are looking for,” 8, Defense & Security Analysis, 36, no. 1 (2020), 30–41; Sidharth Kaushal, James Byrne, Joe Byrne and Gary Somerville, “The Yasen-M and the Future of Russian Submarine Forces,” RUSI, May 28, 2021, https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/rusi-defence-systems/yasen-m-and-future-russian-submarine-forces; Andrew Metrick, “(Un)Mind the Gap,” Proceedings, 145, October 2019, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2019/october/unmind-gap; Rolf Tamnes, “I. The Significance of the North Atlantic and the Norwegian Contribution,” 21-22, In Whitehall Papers: NATO and the North Atlantic: Revitalising Collective Defence, ed. John Andreas Olsen, 87, no. 1 (2016), 8-31; Bradford Dismukes, “The Return of Great-Power Competition — Cold War Lessons about Strategic Antisubmarine Warfare and Defense of Sea Lines of Communication,” 9, Naval War College Review 73, no. 3 (2020), Article 6.

[33] Presentation given by a leading officer of a NATO member state navy’s planning department at a naval conference in 2022.

[34] According to NATO Doctrine (Allied Joint Publications AJP 3.1 ‘Allied Joint Doctrine for Maritime Operations’), “Sea Control is a temporary condition that exists when one has freedom of action within a maritime area for one’s own purposes in the subsurface, surface, and above-water environments and, if necessary, deny its use to an opponent.” Noteworthy, sea control requires the establishment and maintenance of a recognised air, surface and subsurface maritime picture (RMP) – probably the most challenging maritime task on every level of operation. On the operational level, it is also the second key function beside deployment to the right place at the right time. These activities, which make use of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) means, are sometimes summarised as “scouting operations.”

If there are only insufficient ISR means, “sea denial” operations might be necessary. According to AJP 3.1, “Sea Denial is exercised when one party prevents an adversary from using a maritime area. Classic means of achieving sea denial are to lay a minefield or deploy submarines to threaten enemy surface and subsurface forces. Sea denial can be attained using direct or indirect methods.”

[35] An acronym for Greenland, Iceland and the United Kingdom. The gap refers to the two sea zones among these three landmasses that separate the Norwegian Sea and the North Sea from the open Atlantic Ocean.

[36] Nordenman, The New Battle for the Atlantic, 136.

[37] Thomas Nilsen, “Busy day for Russian military in the skies above Arctic,” The Barents Observer, last modified March 30, 2021, https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/security/2021/03/busy-skies; Tass, “Two Russian Tu-95MS strategic bombers perform flight over Barents, Norwegian Seas,” last modified August 14, 2024, https://tass.com/defense/1829153.

[38] The term “bastion” describes the sanctuary for Russia’s sea-based second-strike capability in the Arctic and the Sea of Okhotsk which is protected by a defensive perimeter guarded by the Russian Navy’s general-purpose naval forces. See, for example, Norman Polmar, The Naval Institute Guide to the Soviet Navy, 5th ed. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991), 25; Tamnes, “I. The Significance of the North Atlantic and the Norwegian Contribution,” 9, 11.

[39] Grove, “NATO as a maritime alliance in the Cold War,” 583; Dismukes, “The Return of Great-Power Competition — Cold War Lessons about Strategic Antisubmarine Warfare and Defense of Sea Lines of Communication,” 9; Tamnes, “I. The Significance of the North Atlantic and the Norwegian Contribution,” 13.

[40] Dismukes, “The Return of Great-Power Competition,” 12-13; For NATO deployments to the high north, see, for example, Thomas Nilsen, “Norway invites hundreds of U.S. Marines to the north,” The Barents Observer, last modified June 12, 2018, https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/security/2018/06/norway-invites-hundreds-us-marines-north; Astri Edvardsen, “US Gerald R. Ford Carrier Strike Group to Operate in the High North,” High North News, last modified 26, 2023, https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/us-gerald-r-ford-carrier-strike-group-operate-high-north; Lee Willett, “NATO Navies Demonstrate Sustained Scale In Steadfast Defender,” Naval News, last modified February 23, 2024, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2024/02/nato-navies-demonstrate-sustained-scale-in-steadfast-defender/.

[41] Sidharth Kaushal, “Lessons for the Royal Navy’s Future Operations from the Black and Red Sea,” RUSI, last modified July 26, 2024, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/lessons-royal-navys-future-operations-black-and-red-sea; Department of the Navy, “Naval Doctrine Publication 1: Naval Warfare,” 40.

[42] The mission objective: successfully reinforcing and sustaining NATO forces in Central and Eastern Europe under conditions of high-intensity war.

[43] Hughes and Girrier, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 147.

[44] Ihor Kabanenko, “Strategy in the Black Sea and Mediterranean,” 42, In Russia’s Military Strategy and Doctrine, eds. Glen E. Howard and Matthew Czekaj (Washington D.C.: The Jamestown Foundation, 2019), 34-74; Thomas Fedyszyn, “Russia’s Navy Rising,” National Interest, 28 December, 28 2013, https://nationalinterest.org/ commentary/ russias-navy-new-red-storm-rising-9616.

[45] IISS, “The Military Balance,” 124, no. 1 (2024).

[46] Hughes and Girrier, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 161.

[47] Bundeswehr, “Nach Neptune Strike ist vor Neptune Strike,” last modified March 02, 2023, https://www.bundeswehr.de/de/organisation/marine/aktuelles/neptune-strike-2023-5591522.

[48] Black Sea News, “Deployment of Russian Warships in the Mediterranean as of November 1, 2023,” November 04, 2023, https://www.blackseanews.net/en/read/210586; H I Sutton, “Unusual Russian Navy Concentration Seen In Eastern Mediterranean,” Naval News, last modified February 24, 2022, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2022/02/unusual-russian-navy-concentration-seen-in-eastern-mediterranean/.

[49] Black Sea News, “Deployment of Russian Warships in the Mediterranean as of November 01, 2023.”

[50] Kaushal, “Lessons for the Royal Navy’s Future Operations from the Black and Red Sea.”

[51] Andreas Schmidt, “Countering Anti-Access / Area Denial Future Capability Requirements in NATO,” last modified January 2017, The Journal of the JAPCC, ed. 23, https://www.japcc.org/articles/countering-anti-access-area-denial/; Sergey Sukhankin, “The S-400–Pantsir ‘Tandem’: The New-Old Feature of Russian A2/AD Capabilities,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, 15, no. 14, https://jamestown.org/program/s-400-pantsir-tandem-new-old-feature-russian-a2-ad-capabilities/.

[52] Mike Glenn, “Russians accidentally shoot down one of their own jet fighters, say U.K. officials,” The Washington Times, last modified April 08, 2024, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2024/apr/8/russians-accidentally-shoot-down-one-of-their-own-/; Verity Bowman, “Russian air defences shoot down their own top fighter jet,” The Telegraph, last modified October 05, 2023, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/world-news/2023/09/29/ukraine-russia-war-live-zelensky-putin-meets-troshev-latest/.

[53] Marek Grzybowski, “Port of Alexandroupolis in global logistics NATO chain,” Baltic Sea & Space Cluster, last modified August 27, 2023, https://www.bssc.pl/2023/08/27/port-of-alexandroupolis-in-global-logistics-chain/; NATO, “NATO’s military presence in the east of the Alliance,” last modified July 08, 2024, https://www.nato.int /cps/en/natohq/topics136388.htm.

[54] Tobias Kollakowski, “Early 21st Century Russian Naval Strategy at Europe‘s Southern Maritime Flank: Continental Power, Fleet Design and Naval Operations,” PhD Thesis, King’s College London, 2023, https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/studentTheses/early-21st-century-russian-naval-strategy-at-europes-southern-mar, 141-142.

[55] Esther Castillejo, David Muir and Almin Karamehmedovic, “US Navy rear admiral to ABC News’ David Muir: ‘The Russians are very active and we’re active with them,” ABC News, last modified November 05, 2019, https://abcnews.go.com/International/uss-florida-submarine-admiral-david-muir-russians-active/story?id=66 745121.