Abstract: Technological advancements and evolving security policies increasingly shape military conflicts through AI, autonomous systems, and cyber capabilities. Future developments can be analysed from both military-technological and tactical perspectives, highlighting challenges in command structures, information processing, and execution. The vignettes address the aspects of capability, understanding, and will, i.e., the parts of combat power. Countermeasures require cybersecurity, intelligence validation, and leadership training in cognitive resilience, as well as the proper usage of the decision-making process. Success depends on integrating technology with adaptive command structures and cognitive flexibility. Clausewitz’s adaptability is vital in modern conflicts, while Jomini’s structured approach remains relevant for technological coordination. True success integrates both perspectives, ensuring leadership, data integrity, and the flexibility to shape complexity rather than merely react to it.

Problem statement: How can emerging technologies alter the requirements for the command-and-control system, with a focus on information and communication, and tactical planning?

So what?: The problem statement requires a combination of individual preparation through reading, learning, thinking and creative experimentation, alongside institutional preparation that fosters thinking beyond conventional boundaries by nature. This dual approach is essential for meeting the demands of future conflicts effectively and should be implemented immediately in training.

Source: shutterstock.com/Eugene Onischenko

Technological Innovation and War

In light of rapid technological advancements and evolving security policy frameworks, a critical examination of future military conflicts is becoming increasingly indispensable. Future battles are expected to be shaped by the close integration of technological innovations—such as artificial intelligence, autonomous systems, and advanced cyber capabilities—with the adaptation of military tactics. These developments pose fundamental challenges for military personnel concerning command structures, information processing, and tactical execution.

Future battles are expected to be shaped by the close integration of technological innovations—such as artificial intelligence, autonomous systems, and advanced cyber capabilities—with the adaptation of military tactics.

This study explores this complex field from two complementary perspectives. On the one hand, the military-technological perspective is analysed, examining the requirements for command and information systems as well as command relationships. On the other hand, the focus is placed on the tactical perspective, which addresses the planning and execution of combined arms operations. Based on theoretical foundations, three hypothetical vignettes have been developed to illustrate the impact of modern, emerging technologies on military operations. The first scenario demonstrates how systemic cyberattacks, such as the sabotage of weapons systems, can severely compromise a battalion commander’s operational capabilities. The second scenario focuses on the domain of situational understanding, depicting a brigade general confronted with an electronically manipulated operational map due to enemy interference. The third scenario highlights the psychological dimension, showing how coordinated psychological operations—including leaflets, social media attacks, and deepfakes—can profoundly undermine trust and cohesion within military units.

Methodology

In this research project, various future scenarios were generated—among other approaches—using an AI application (ChatGPT 4o). The prompts employed and excerpts from the AI-generated texts are documented in the references to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and verifiability. This documentation ensures that AI-based content meets established scientific standards. The use of AI is explicitly conducted within the framework of scholarly diligence. Despite the computer-assisted support, the research outcomes remain critically examined and theoretically grounded, thereby minimising potential biases and maintaining scientific quality.

Although this approach slightly deviates from the original mixed-methods design in purely qualitative and quantitative perspectives, it nonetheless combines various methods. Specifically, blending a creative, exploratory, and predominantly qualitative approach with a strong quantitative grounding in the literature offers both breadth and scientific rigour when examining future challenges.[1]

As a first step, various technical and military domains—such as attack vectors in electronic warfare and cyber warfare—were synthesised. Current (2025) Technology Readiness Levels were considered to assess technological advancements and develop plausible future scenarios for 2035. Drawing on these parameters, the AI developed a series of fictional “interviews from the future,” depicting potential actors and operational scenarios. This creative method served to outline hypothetical but realistically grounded visions of the near future.

They were subsequently compared with existing military literature to assess the realism and plausibility of the generated scenarios. This comparison helped validate the identified trends, risks, and opportunities and tested basic military principles. Consequently, a dual assurance strategy was implemented: on one hand, creative, AI-based scenario generation; on the other, cross-referencing with recognised, peer-reviewed literature.[2]

Scenarios

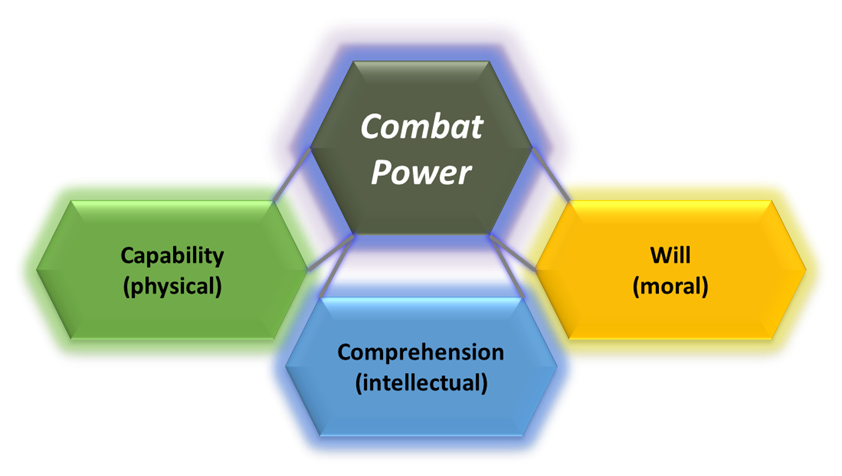

Warfare has always been more than just the clash of weapons on the battlefield. Victory is not solely determined by firepower but by a combination of interwoven factors that define a military force’s overall combat power. Three fundamental pillars shape the effectiveness of any fighting force: capability, understanding, and morale. Each of these elements plays a decisive role in determining the outcome of a battle, and an adaptive enemy can disrupt, manipulate, or even weaponise it.

The Fundamentals of Combat Power; Source: Authors.

The following scenarios illustrate how modern warfare increasingly targets these three dimensions, rather than relying purely on conventional engagements. The scenarios are presented in a deliberate order, reflecting how combat power can be systematically degraded.[3]

Capability

First, the capability scenario examines how an enemy can neutralise a force’s ability to fight by sabotaging technology, disabling weapons systems, and exploiting vulnerabilities in cyber infrastructure. Without functional equipment and effective firepower, even the most well-trained forces are rendered ineffective. The detailed prompt is provided in the footnotes.[4]

I stand among the smoking remains of my battalion. The vehicles are destroyed, and the voices of the few survivors flicker through the radio. Our anti-air platoon, once our shield against drones, was the first to fall—specially fabricated chips in the fire control units had been infiltrated. When exposed to the enemy drones’ electronic emissions, they overheated and burned out. The systems collapsed, and our positions were bombarded without resistance. Our tank company, the core of our firepower, failed next. The AI-supported targeting software had been hacked; enemy tanks were detected, but every shot missed by a few crucial meters. It was as if our rounds were deliberately misdirected. Crews reported growing despair as shot after shot failed. Then came the infantry fighting vehicles. Their driver consoles displayed a constant warning: “Replace Burgmannring.” This minor but critical seal was falsely flagged as defective through satellite-based software manipulation. The vehicles halted automatically, becoming easy targets, even though the components were intact. Communication and logistics broke down under enemy electronic warfare. Reports didn’t get through. Ammunition convoys were destroyed before reaching us. Even our artillery, fed false GPS data, fired far off target. The result was chaos. My soldiers lost faith—not just in their weapons, but in the entire operation. Morale collapsed. Now, I stand in the ruins, realising we placed too much trust in systems we didn’t fully understand or protect. Our technological edge wasn’t our strength—it was our Achilles’ heel. This must never happen again.[5]

Technical Considerations

From the standpoint of command support and IT specialists, safeguarding operational integrity in contemporary warfare hinges on a systematic and multifaceted approach. On the one hand, advanced technologies can significantly enhance both situational awareness and mission effectiveness; on the other, they introduce a range of digital vulnerabilities that adversaries are poised to exploit. To mitigate these risks and maintain a decisive edge, three critical dimensions merit particular attention:

- Bolster Supply Chain Vigilance and Real-Time Systems Integrity. Never let advanced systems lull you into complacency—true security demands relentless vigilance. The priority is supply chain security because infiltration at the microchip level can compromise even the mightiest arsenal. Where a single line of malicious code or an unverified component can neutralise entire fighting forces, meticulous oversight at each production stage and thorough patch management become non-negotiable, ensuring that no Trojan horse slips through unseen;[6]

- Reinforce C2 Structures with Adaptive Info-Sharing and Human Oversight. Resilient command and control relies on more than just robust encryption and adaptive network architecture; it also demands human oversight that can interpret anomalies and pivot rapidly under stress. Communication breakdown erodes a unit’s morale and disrupts mission execution, but empowered signals officers who know how to detect and counter electronic warfare tactics can preserve unity of effort. Relying solely on automated systems, however advanced, leaves operations vulnerable to well-timed enemy disruptions that undermine situational awareness and expose critical nodes; and

- Cultivate Cyber-Conscious Leadership and a Tech-Savvy Force. Leaders must integrate cyber-awareness into every echelon, transforming soldiers into active sensors who can identify threats—physical or digital—at the first sign of danger. An educated force spots deception attempts early and responds with agility, making it far harder for an enemy to manipulate a battlefield with compromised data. When the entire chain of command is engaged, from the rifleman to the battalion staff, complacency cannot take root, and technology serves as a force multiplier rather than a point of failure.[7]

Never let advanced systems lull you into complacency—true security demands relentless vigilance.

Tactical Considerations

From a tactical perspective, one is confronted with a fait accompli in this situation. However, to prevent a similar scenario, various methods and measures can be employed.

- Know.Think.Act.[8] NATO’s Mission Command doctrine[9] emphasises decentralised decision-making and individual responsibility, yet its absence in this scenario proved catastrophic. Leaders must be trained to think critically and act independently, ensuring they can adapt dynamically when technological systems fail. The battalion’s reliance on centralised, automated processes led to paralysis when cyber sabotage rendered key systems inoperable. Focusing on the human factor means developing leaders who can process incomplete information, challenge assumptions, and maintain initiative under uncertainty. A force overly dependent on rigid structures and maybe also technology as its only means becomes predictable and vulnerable. Only a (military) culture that prioritises adaptability over procedural obedience ensures resilience in the chaos of modern warfare. This necessitates a training culture prioritising analytical thinking over procedural obedience, ensuring tactical effectiveness is driven by adaptability rather than rigid adherence to pre-planned structures. So, to sum up, it is not sufficient to merely follow the military-decision-making (MDMP, military-decision-making-process) steps; they must be understood and, if necessary, adapted;

- Look sharp, stay sharp, strike hard. Safety first is not about hesitation—it is about controlling the fight before it starts. The battalion’s failure was not due to a lack of aggression but overconfidence in its technology, leading to total vulnerability when systems were compromised. Seizing the initiative requires confidence, but blind reliance on automation replaces tactical awareness with complacency. Commanders must maintain composure under pressure, prioritise reconnaissance and verify their battlespace before committing forces. A methodical, intelligence-driven approach—balancing deception, preemptive reconnaissance, and calculated aggression—ensures that engagements happen on their own terms. A battle is won before it begins, not through technological superiority alone, but through positioning, foresight, and the ability to dictate tempo;[10]

- Double Tap. Tactical decisions must be based on assessed facts and executed through combined arms warfare, yet the battalion’s reliance on automated targeting systems led to widespread failure. The principle of main effort[11] dictates that multiple weapon systems should engage a single enemy target simultaneously, maximising effectiveness. However, the cyber sabotage that crippled targeting systems and air defence units exposed a fatal flaw—a lack of redundancy and synchronised firepower. Just as Austria’s old anti-tank recoilless rifle doctrine required two firers per target, modern forces must apply this principle across entire structures. Firepower synchronisation, complementary asset deployment, and the integration of supporting multi-domain effects given by the operational level must be embedded in tactical planning to ensure resilience against electronic warfare and sabotage.

Commanders must maintain composure under pressure, prioritise reconnaissance and verify their battlespace before committing forces.

Understanding

Second, the understanding scenario delves into the confusion sown by digital deception. Manipulated battlefield intelligence, falsified situational awareness, and cyber-induced disinformation can cloud a commander’s ability to assess the battle correctly. A force that cannot trust its own information is left paralysed, unable to act decisively. The prompt used can be seen here:[12]

It was a grey morning, and the command post of the 12th Armoured Brigade buzzed with activity. Brigadier General Lothar von Greiffenstein was moments away from transmitting the attack order when he noticed something odd on the digital situational map: the enemy’s positions had changed dramatically within minutes. What had been a lightly defended ridge now appeared to be abandoned while heavy armour advanced toward his flank. His staff was confused—no new drone data had been received, no scouts had reported back. The map had updated itself. It soon became clear that they were victims of a sophisticated deception. The enemy had exploited vulnerabilities in satellite networks, injecting false data into their systems through forged transmissions that mimicked legitimate reconnaissance feeds. This was paired with a malware update that visually manipulated the brigade’s tactical display. The entire battlefield picture was false. In truth, the enemy had reinforced their lines and prepared artillery for a devastating counterattack. Communications were overloaded, and field reports were delayed or missing. Von Greiffenstein realised he was planning an assault based on a fabricated reality. A hasty attack meant walking into a trap; retreating risked other unknown dangers. He ordered system integrity checks, re-flights of drones, and encrypted reports from forward observers. Ultimately, he delayed the attack, avoiding disaster—but the damage was done. The brigade was paralysed by confusion. Later analysis confirmed: lax cybersecurity and digital overdependence had crippled their understanding. “Next time,” the general thought grimly, “we verify the truth—before we act on it.”[13]

Technical Considerations

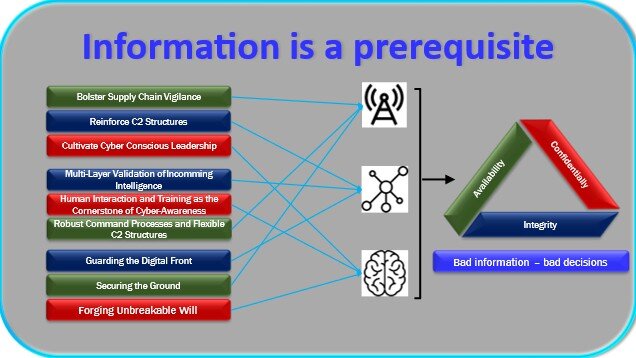

From an IT and command support perspective, ensuring operational integrity in modern warfare fundamentally depends on safeguarding information and its underlying data. Mitigating inherent risks requires strict adherence to the CIA principle of data—Confidentiality, Integrity, and Availability—to secure, maintain, and guarantee reliable access to critical resources:

- Multi-Layer Validation of Incoming Intelligence. The chaos stemmed from the brigade’s exclusive reliance on a single digital feed, highlighting the risk of data manipulation when no alternative verification tools are employed. Multi-layer validation—where each data point from reconnaissance drones, forward observers, and satellite feeds is cross-checked via firewalls or even Information Exchange Gateways—can detect discrepancies early and expose deception. Checking metadata and Network Intrusion Point allows faulty data to be sorted quickly.[14] Only by instituting rigorous vetting procedures and routine integrity checks on critical systems can command staff keep false intelligence from derailing operational plans;

- Human Interaction and Training as the Cornerstone of Cyber-Awareness. Technical safeguards alone cannot offset the human element when identifying cyber or electronic warfare assaults. Well-trained personnel, from signals officers to frontline soldiers, are indispensable in noticing anomalies—such as erratic changes in enemy positions—and raising red flags. Mandating regular cyber-awareness courses and scenario-based exercises ensures that operators develop the necessary scepticism to challenge suspicious data inputs. This human-centric approach, combined with robust cybersecurity measures, transforms each soldier into an active sensor, minimising the chance of digital deception crippling the entire force;[15]

- Robust Command Processes and Flexible C2 Structures. Even the most advanced technology proves ineffective when crisis management and leadership frameworks are underprepared. In this scenario, the brigade faced sudden paralysis because decision-makers lacked the structures and doctrines to pivot quickly under digital duress. A resilient command and control model trains officers to question sudden shifts, enact fallback protocols, and sustain the flow of information through redundant communication channels. By embedding crisis simulation exercises and contingency planning into regular drills, leadership teams become adept at rapidly adapting to deceptive signals on the battlefield.[16]

Technical safeguards alone cannot offset the human element when identifying cyber or electronic warfare assaults.

Tactical Considerations

- Two is one, one is none. Establishing dual communication links is standard in defensive operations, as the authors learned throughout training, ensuring continuous command and control even under enemy interference. However, this principle is often neglected in offensive operations, where single-point failures can lead to total mission breakdown. Layered communication infrastructures—incorporating analogue, digital, and human relay systems—must be standard practice across all domains. Combining motorised and mechanised messengers with encrypted digital channels enhances operational resilience. The redundancy mindset must extend beyond communication to intelligence gathering, ensuring that no single reconnaissance method becomes a critical point of failure;

- No limits—just possibilities. Stop focusing on perceived restrictions—focus on what is still operational and how to maintain control. The brigade command post became paralysed by manipulated intelligence and disrupted communications, yet mission success depended on adaptability, not perfect information. In NATO doctrine, constraints define mission parameters, while restraints impose explicit prohibitions.[17] While these structures ensure discipline, they must never override initiative-driven problem-solving. Tactical flexibility is not reckless improvisation—it is a deliberate approach to maintaining freedom of action within disruption. However, flexibility is only effective when underpinned by deep tactical proficiency. Commanders must train for uncertainty, ensuring subordinates can operate even when the digital battlefield is compromised;

- Practice chaos,[18] master control. Integrating continuous wargaming into command procedures enhances operational awareness and prepares leaders for unexpected developments—exactly the kind that paralysed the brigade in this scenario. The Austrian Armed Forces recognise Kriegsspiel (wargaming for synchronising or evaluating different courses of action, but also for rehearsing the concept of ROC, depending on when it takes place).[19] Still, its application is often limited to the planning phase instead of using it as a tool to stress the ongoing battle from the enemy´s point of view during live execution. This approach restricts its effectiveness as an adaptive tool. Red Teaming must be an active element of command processes, allowing leaders to simulate/stress test courses of action in real time with real and trained personnel and validate decisions under uncertainty. This is not just an academic exercise—it is a tactical necessity.

Tactical flexibility is not reckless improvisation—it is a deliberate approach to maintaining freedom of action within disruption.

Will and Morale

Finally, the morale scenario explores the long-term effects of psychological warfare. Beyond physical destruction, modern adversaries increasingly seek to erode trust, spread fear, and dissolve cohesion through propaganda, social engineering, and deepfake technology. Once doubt and paranoia take root, a military force may collapse from within, even before the enemy delivers a final blow.[20]

The battle had become a nightmare. Corporal Lukas Hoffmann crouched behind a burned-out vehicle, his rifle limp in his hands. Gunfire and explosions echoed around him, but the real damage wasn’t physical—it was psychological. His digital map flickered uselessly, distorted and confusing. Morale in the unit had collapsed, not from enemy fire, but from an invisible assault on their minds. It started with digital manipulation: false data, shifting enemy positions, erratic system behaviour. Soon, targeting systems failed, and comms were compromised. Every decision became uncertain. Then the propaganda began—flyers dropped by drones, chain messages on personal devices, fake social media posts: “Your commander has betrayed you,” “You’ve been abandoned.” They weren’t true, but they planted doubt. Then came the deepfake—video of their commander apparently surrendering to the enemy. It spread through their secure network like wildfire. Everyone knew it was fake, but trust shattered anyway. Soldiers began to suspect one another. Paranoia grew. And then the most personal attack of all: a message to Hoffmann’s sister, claiming he would soon be dead. It cut deeper than any wound. That was when he realised—this war wasn’t about bullets or tanks. It was about belief. About will. As morale crumbled, his platoon leader’s voice pierced the fog: “The enemy can only defeat us if we let them. If we lose our heads, we lose the war.” Somehow, they held together. Scarred, shaken—but not broken. Hoffmann understood then: the true battlefield was the mind. And surviving meant fighting to stay human.[21]

Technical Considerations

From an IT and command support perspective, safeguarding operational integrity in modern warfare demands a holistic approach encompassing physical, virtual, and cognitive realms. While the physical domain involves hardware, infrastructure, and tangible assets, the virtual domain focuses on digital networks and data flow. The cognitive realm, in turn, addresses human perception, decision-making, and information interpretation. These three sub-domains are deeply interwoven: compromised infrastructure jeopardises network functionality; breaches in virtual systems erode user confidence and strategic advantage; and misinformation in the cognitive space can undermine even the most sophisticated technological safeguards.

While the physical domain involves hardware, infrastructure, and tangible assets, the virtual domain focuses on digital networks and data flow.

- Guarding the Digital Front. The enemy effectively corrupted battlefield data and disseminated deepfake propaganda by targeting the digital interfaces that soldiers rely upon. Mitigating such threats requires a fortified virtual domain, where rigorous authentication protocols and multi-layered encryption shield command networks from exploitation.[22] Rapid threat detection, continuous system auditing, and robust backup communication channels are the virtual bulwark, ensuring that malicious software and fabricated messages cannot rapidly undermine confidence or disrupt mission continuity;[23]

- Securing the Ground. Even the best-protected signal infrastructure becomes vulnerable if fundamental physical security lapses occur. Personnel must secure command posts, safeguard data centres, and rigorously vet on-site hardware to prevent infiltration and sabotage. Physical-domain protocols—from perimeter defence and equipment inspections to secure logistical chains—complement digital protections by minimising the chances of unauthorised access or tampering at the source. Such tangible measures reinforce the integrity of information systems and support broader resilience in high-intensity operations;

- Forging Unbreakable Will. Ultimately, morale shatters when soldiers lose trust in their tools, leaders, and each other—a vulnerability the enemy weaponises through psychological warfare. Resilient command structures must incorporate regular training in cognitive resilience, where troops learn to recognise and counter both subtle and overt manipulation. Commanders who rapidly debunk false narratives, foster open communication, and encourage critical thinking transform fear into collective vigilance, preserving the fighting spirit that technology alone cannot guarantee.[24]

Morale shatters when soldiers lose trust in their tools, leaders, and each other—a vulnerability the enemy weaponises through psychological warfare.

Tactical Considerations

If the tactical framework is insufficiently established, the battle will ultimately be lost at the combat-technical level. Conversely, this also clearly demonstrates the significance and effectiveness of applicable regulations and leadership tools.

- Fool me once—never twice. Every battle must be analysed not only for tactical efficiency but also for its psychological impact. Tactical debriefings and step-by-step control mechanisms must be embedded into command procedures to ensure continuous learning and resilience against enemy means. Experience alone does not guarantee improvement—structured analysis does. After-action reviews must extend beyond technical errors, incorporating morale, trust, and all means of enemy warfare into the assessment. Commanders must train their units to analyse engagements holistically, identifying vulnerabilities in will, understanding, and capability. Understanding how disinformation, psychological pressure, and internal distrust impact effectiveness is just as critical as evaluating direct combat performance. Only through systematic institutional learning can forces develop the adaptability needed to counter physical threats and the invisible weapons of modern warfare.

- The ground fights with you—if you use it right. The battlefield in this scenario consisted of a dense forested area interspersed with open fields and urban ruins, but this should now not be the level of consideration; it has to be understood in the following manner: „As the terrain enables, enforces, or restricts certain actions for both one’s own forces and opposing parties, the resulting conclusions either complement or adjust the possibilities of the conflicting sides.“[25] At this analysis stage, the focus must shift from observation to application—the external influences must now be viewed in a more abstract, distanced manner, transitioning from a passive assessment to an active tool. Austrian military doctrine defines the Terrain Effects on Friendly Operations as follows: „In this assessment step, the possibilities offered by the terrain are analysed based on previously drawn conclusions and aligned with one’s own operational capabilities.“[26] That is, in fact, the key transition point from analysis to synthesis.[27] Here, the question is no longer what has to be done but how it can be achieved, which element can be used to generate the right effect, and how the environment in general shapes this employment. This must under no circumstances be interpreted as a mere assessment of the terrain; rather, it concerns ensuring the optimal application of combat power within the established framework by accounting for all external influencing factors.

Only with the right combination of troops and a deep understanding of the factors can the elements be effectively employed—a necessity that becomes evident in the next section.

- Trust wins battles. „The trust between senior leaders in the command was able to overcome the stress of combat, […].“[28] Trust is the invisible backbone of combat power. Without it, even the most advanced forces fail. Commanders must cultivate both horizontal trust among troops and vertical trust between leadership and subordinates. This requires clear intent, decentralised execution, and demonstrated competence at all levels. However, trust does not emerge by itself—it is built when soldiers feel properly led. Correctly applying the command process as a structured tool ensures exactly that. When leadership is transparent, consistent, and methodical, subordinates develop confidence in decisions and execution. This may, for example, require that during peacetime, decisions are given with justifications[29] to familiarise subordinates with the commander’s thought process. Trust is earned through shared hardships, disciplined adaptability, and competent guidance in dynamic environments. Leaders must be predictable in intent but flexible in execution, ensuring that troops understand, believe in, and can act on the mission independently.

Trust is the invisible backbone of combat power.

Endgame?

Lose smart, so you can win again. Defeat is inevitable in warfare, but its impact must be managed. A lost engagement should not mean operational failure. Commanders must identify unnecessary destruction when continuing to fight risks and ensure structured withdrawal, force preservation, and morale retention. As recognised by Reinhard Janko during the TMAF24,[30] defeat shall be part of the tactical training. The importance lies in recognising failure as a chance to learn. Debriefing frameworks, red-team exercises, and contingency-based wargaming refine decision-making and prevent repeated mistakes. Training should simulate failure scenarios to develop leaders who can analyse, adapt, and recover quickly, turning setbacks into strategic learning opportunities.

Food for Thought – Technical

Before addressing the final considerations from an IT technician and signals officer’s perspective, it is essential to weave together the key strands of technology, leadership, and human resilience. Although these principles resonate across operational and strategic spheres, the immediate focus is on preventing tactical collapse. The conclusion condenses these insights, demonstrating how synergy across virtual, physical, and cognitive domains preserves battlefield momentum and morale.

Defence demands more than technical fixes in a battlespace where hidden code can disable key hardware, where deepfake propaganda seeds mistrust, and where a single compromised data feed can unravel entire operations. Information is a prerequisite; bad information usually leads to bad decisions, as illustrated in the following graphic. It requires an airtight supply chain, adaptable command and control, and a cyber-conscious force unafraid to question every signal. A modern military safeguards its momentum and morale by layering authentication and verification across all digital inputs, securing physical infrastructure against on-site tampering, and training every soldier to see and stop manipulation before it spreads. This synergy across the virtual, physical, and cognitive domains also aligns with the CIA principles: confidentiality is associated with the cognitive domain, integrity upholds the virtual realm, and availability secures the physical environment. Ultimately, neither code nor chaos nor psychological strike can deny victory to those who remain vigilant.

Defence demands more than technical fixes in a battlespace where hidden code can disable key hardware, where deepfake propaganda seeds mistrust, and where a single compromised data feed can unravel entire operations.

The Key Technical Insights prior to the MDMP; Source: Authors.

Tactical Point of View

The temporary character of warfare does not bind the command process—it is designed to be universally applicable, regardless of time, place, or conditions. It provides the necessary freedom for commanders to execute their mission as the situation demands, rather than forcing a rigid approach onto a fluid battlespace. Abstracting decision-making into a structured yet adaptable framework ensures that leadership remains effective even in the future environment—always shaped by mission needs, never by doctrinal constraints.

This structured flexibility directly enhances combat power, ensuring that forces are not just deployed but employed effectively. Troops and resources must be assigned where they have the greatest impact, avoiding inefficient applications. A command process that correctly assesses the mission, enemy, terrain, and available forces guarantees that each asset is used to maximise its strengths. By ensuring a coherent and synchronised approach, the command process increases the force’s effectiveness. The graphic below precisely explains this system. The key conclusions from the scenarios have been assigned to the steps of the MDMP—orientation (M), the enemy (E), the terrain (T), and own forces (T) and focus on the employment of combat power (E), the main task of the tactical echelon. If something still goes wrong, learn from it!

The Key Insights connected to the MDMP; Source: Authors.

As a result, trust between commanders and troops emerges naturally. Soldiers trust leaders who provide clear intent, execute decisively, and apply force efficiently. A unit that sees competent, structured leadership will fight with confidence and cohesion, knowing their role is understood and their mission achievable.

Finally, if defeat becomes inevitable, it must remain an isolated event—never a pattern. A structured command system ensures that losses are analysed, learned from, and prevented in the future. Tactical setbacks should lead to institutional adaptation, ensuring vulnerabilities are permanently addressed. Forces integrating continuous learning and structured command adaptation will always recover stronger, maintaining the initiative. A structured command system turns failure into future success, ensuring that vulnerabilities are addressed permanently—never exploited twice.

Tactical setbacks should lead to institutional adaptation, ensuring vulnerabilities are permanently addressed.

“Military leadership is a guiding, controlling, and motivating influence on commands, troops, units, and individuals to achieve objectives and optimise organisational effectiveness. It involves the targeted deployment of resources, means, and information across time and space. Leadership is a continuous process that relies on the prerequisite of mutual information exchange.“[31]

Balancing Technology and Human Judgment

Combat power is built on three fundamental pillars: capability, understanding, and morale. While these elements define a force’s effectiveness, they are not static—they must be continuously developed, reinforced, and sustained. Capability stems from equipment, training, and doctrine, but it is only as effective as the understanding that enables its proper use. Without clarity in mission execution, even the most advanced systems become ineffective. Morale, the decisive factor in prolonged engagements, is shaped by leadership, trust, and confidence in the mission. Just as these components can be cultivated, they can also be solidified through proper application. These future-oriented examples demonstrate how combat power is not merely an asset to be measured—it is a dynamic force that must be built, maintained, and reinforced through deliberate command decisions.

From the tactical point of view, it is rather simple. In modern warfare, particularly in hybrid, cyber, and asymmetric conflicts, a Clausewitzian approach—rooted in deductive reasoning—proves superior to Jomini’s more mechanistic doctrines, which rest upon an inductive framework. The unpredictability of contemporary battle spaces demands adaptability, intuition, and, on the tactical level, a deep understanding of the military dimension of war. The outlined principles—regarding the mission, the enemy, the terrain and one’s own troops—reflect this mindset. War is not a formulaic equation but a dynamic struggle of wills. Effective leaders embrace uncertainty, human factors, and operational flexibility over rigid structures. To prevail, commanders must think critically, act decisively, and master chaos—more Clausewitz, less Jomini. Victory belongs to those who shape complexity, not those who merely calculate it.

From a technical standpoint, the situation proves far more intricate than it may initially appear. In modern conflict environments, one might argue that a Clausewitzian perspective, emphasising will, uncertainty, and the human dimension, offers clear advantages. Nonetheless, it is critical to recall that Jomini, as a mathematician, consistently foregrounded warfare’s granular and formulaic nature. Yet Clausewitz and Jomini do not operate on the same level of command, and their distinct deductive or inductive approaches cannot be directly compared. Instead, their respective viewpoints must be integrated.

In modern conflict environments, one might argue that a Clausewitzian perspective, emphasising will, uncertainty, and the human dimension, offers clear advantages.

One might well argue that adopting a “mixed-methods” approach proves most advisable. While Clausewitz’s insights into the fluidity and unpredictability of war underscore the significance of human judgment, Jomini’s focus on structure and calculation underlines the importance of precise coordination at every level. In particular, the reliable transmission of data—even down to each bit and byte—is indispensable: information must be correctly addressed, securely transmitted, and properly interpreted. One must never lose sight of the fact that information stands as a fundamental prerequisite for success. When these foundations are in place, tactical flexibility, human intuition, and operational innovation flourish. While victory may indeed favour those adept at shaping complexity, such success is impossible without an underlying comprehension of the technical architecture. Commanders who neglect the intricacies of data management and security risk fighting against the very “ghosts” they themselves created. Although the theatre of modern warfare increasingly spans digital realms, the fundamental need for both rigid structural safeguards and adaptive, human-centred leadership remains undiminished.

Captain Johannes Ginthör is currently chief instructor at the Theresan Military Academy and an alumnus of the 23rd General Staff Training of the Austrian Armed Forces. As a PhD candidate at the University of Vienna, he has research interests in military operations ranging from tactical training and planning to the usage of the military as a governmental instrument in general. Additionally, he holds a Master’s Degree in Military Leadership from the National Defence Academy in Vienna.

Major Markus Schmid is a passionate leader with a strong focus on Cybersecurity, AI, and IT, supported by extensive military experience. He holds a Master’s in Computer Science from FHWN and a Master’s in Military Leadership from the National Defence Academy in Vienna. He is furthermore an alumnus of the 23rd General Staff Training of the Austrian Armed Forces, a PhD candidate at the University of Vienna and is keenly interested in disruptive technologies and their potential to drive innovation.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Austrian Armed Forces.

[1] J. W. Creswell and V.L.P. Clark, Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (SAGE Publications, 2017), https://books.google.at/books?id=eTwmDwAAQBAJ.

[2] Paul Schoemaker, “Scenario Planning: A Tool for Strategic Thinking,” Sloan Management Review 36 (1995): 26-31.

[3] “I would like to shed light on three future war or conflict scenarios for a more in-depth analysis and derive conclusions for training from them. I will now roughly describe the three scenarios to you, along with what I want; please formulate them accordingly. Mentally, we are in the year 2035, and the fictional country in the scenario is at war. All three scenarios focus on the three components of combat effectiveness: morale (the will of the soldier), understanding (understanding the situation and the resulting task), and capability (sufficient physical resources such as tanks, anti-aircraft guns, or ammunition). Please add this to the previous requirements as well!” Sam Altman, ChatGPT 4o (OpenAI, 2025), accessed February 20, 2025, https://chatgpt.com/.

[4] „First scenario, area: capability. Describe, from the perspective of a future battalion commander (three mechanised infantry companies, one tank company, one platoon of self-propelled anti-aircraft systems, one platoon for indirect fire support), why he has just lost a battle against an enemy and now stands before the smoking wreckage of his battalion. Cite as reasons, for example, that the anti-aircraft platoon was unable to fire because the chip supply chain for the fire control computers had been infiltrated or sabotaged. These chips reacted to a specific type of electronic emission in such a way that the entire anti-aircraft software system was overloaded, causing the components to burn out. The main battle tanks failed to hit the opposing tanks because the AI-assisted target acquisition software had been hacked. Upon detecting the contours of enemy vehicles, it consistently produced missed shots due to slight targeting deviations. Finally, describe how the infantry fighting vehicles constantly displayed a message on the driver’s control panel indicating that the component “Burgmannring” urgently needed to be replaced. This was the result of satellite-based interference with the software, which had injected the false alert. Feel free to invent additional background information and elaborate creatively. Also, consider selecting other units from the battalion and constructing similar examples. Length: approximately 600 words, from the perspective of the battalion commander.“ Altman, ChatGPT 4o.

[5] Altman, ChatGPT 4o.

[6] Jon Boyens et al., “NIST – Cybersecurity supply chain risk management for systems and organisations,” (Gaithersburg, MD, 2022), 170-178.

[7] P. W. Singer and A. Friedman, Cybersecurity: What Everyone Needs to Know, What Everyone Needs To Know (OUP USA, 2014), https://books.google.at/books?id=9VDSAQAAQBAJ, 166-176.

[8] Know.Think.Act is the chosen motto of the Austrian 23. General Staff Course.

[9] North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Tactical Planning for Land Forces: APP-28” (2019), 1.

[10] Charles S. Oliviero, Praxis Tacticum: The Art, Science and Practice of Military Tactics (Double Dagger Books Ltd, 2021), 39–40.

[11] Dieter Schadenböck, “Grundlagen der Taktik der Landstreitkräfte: Lehrskriptum,” 2nd ed. (Wien, 2020), 81.

[12] „Now create a second example for the area of Understanding, from the perspective of a brigadier general at his command post, who had just reached for the receiver to issue an order to attack. But now, on the digital situation map, the enemy positions appear completely different from just a few minutes ago, when the operational plan had been presented to him for approval. Try to invent, as creatively as possible, how the enemy might have used technological means to fundamentally deceive the understanding of the entire brigade staff! Again, around 600 words!“ Altman, ChatGPT 4o.

[13] Altman, ChatGPT 4o.

[14] CISA, Zero Trust Maturity Model (2023), Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency; Cybersecurity Division, 9-10.

[15] Singer and Friedman, Cybersecurity: What Everyone Needs to Know, 126-134.

[16] A. King, Command: The Twenty-First-Century General (Cambridge University Press, 2019), https://books.google.at/books?id=IFR-DwAAQBAJ, 358-361.

[17] North Atlantic Treaty Organization, “Tactical Planning for Land Forces,” 2–9.

[18] Oliviero, Praxis Tacticum, 55–58.

[19] Bundesministerium für Landesverteidigung, “Taktischer Führungsprozess: Dienstvorschrift für das Bundesheer” (Wien, 2019), 26-27.

[20] „Now the third scenario, this one focuses on the area of Morale. Invent an example from the perspective of an individual soldier who was part of all these combat operations, but describes that the worst part for him was how the enemy systematically destroyed morale. Come up with all kinds of examples for this – such as flyers, chain emails, social engineering, harassment on Facebook, deepfakes, and much more! Again, roughly 600 words!“ Altman, ChatGPT 4o.

[21] Altman, ChatGPT 4o.

[22] US Army, FM 3-12 – Cyberspace Operations and Electromagnetic Warfare (2021), 18-19.

[23] US Army, FM 3-12 – Cyberspace Operations And Electromagnetic Warfare, 32-41.

[24] Singer and Friedman, Cybersecurity: What Everyone Needs to Know, 231-247.

[25] Bundesministerium für Landesverteidigung, “Taktisches Führungsverfahren: Dienstvorschrift für das Bundesheer” (Wien, 2012), 71.

[26] Bundesministerium für Landesverteidigung, “Taktisches Führungsverfahren,” 78.

[27] Bundesministerium für Landesverteidigung, “Taktisches Führungsverfahren,” 68.

[28] Mick Ryan, White Sun War: The Campaign for Taiwan, 1st ed., Casemate Fiction Series (Casemate Publishers & Book Distributors LLC, 2023), https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/kxp/detail.action?docID=31599283, 164.

[29] In the Austrian Armed Forces, this is known as “Entschluss mit Begründung”.

[30] Reinhard Janko, “Betrachtungen zum manöverbasierten Ansatz in der Taktikausbildung,” (TMAF24, Theresianische Militärakademie, October 10, 2024).

[31] Bundesministerium für Landesverteidigung, “Taktischer Führungsprozess,” 15.